This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

ABSTRACT

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) refers to blastocyst implantation outside the uterine

endometrium. EP is major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Treatment

options include surgery, medical therapy with methotrexate, or expectant

management. Methotrexate is the primary regimen used in cases of early,

unruptured ectopic pregnancies. Most side effects of methotrexate are minor,

including nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and photosensitive skin

reaction. Serious side effects, including bone marrow suppression, and pulmonary

fibrosis, are invariably observed when methotrexate is administered in high

doses with frequent dosing intervals, in chemotherapeutic protocols for

malignancy. These side effects are uncommon with the doses used to treat ectopic

pregnancies. Since cases of methotrexate-induced pancreatitis are rare, we

report a case of pancreatitis in a patient with EP treated with methotrexate and

expect to consider pancreatitis as a side effect of methotrexate in a patient

with upper abdominal pain undergoing methotrexate chemotherapy.

Go to :

Keywords: Pregnancy ectopic, Methotrexate, Pancreatitis

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) refers to blastocyst implantation outside the uterine cavity.

The incidence of EP is rising, which can be explained by the increased use of

assisted reproductive technologies, tubal surgeries, and improved diagnostic tools

[

1]. EP is medically important because it

is associated with reduced fertility and an increased risk of subsequent EPs [

2]. Treatment options for EP involve surgical

and medical intervention [

1]. Medical

treatment primarily uses a regimen of methotrexate (MTX) in cases of early,

unruptured EP, and is reported to be safe and effective [

1].

MTX is a folic acid analog that competitively binds to dihydrofolic acid reductase,

an enzyme that converts dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate. This binding prevents the

reduction of folate to its active form, tetrahydrofolate. It transports one carbon

group during the synthesis of purine nucleotides and thymidylates. MTX impairs DNA

synthesis, DNA repair, and cellular replication [

3]. MTX selectively acts on rapidly dividing cells, such as trophoblast

cells, which comprise the implantation site during early gestation [

4]. MTX enters the liver via the hepatic artery

and is rapidly cleared from the body by the kidneys, with 90% of the intravenous

dose excreted unchanged within 24 h of injection [

5,

6].

Two common regimens are available for MTX: multidose [MTX 1.0 mg/kg intramuscularly

(i.m.) daily; days 0, 2, 4, and 6 alternated with folinic acid 0.1 mg/kg orally on

days 1, 3, 5, and 7]; and single dose (MTX 0.4 to 1.0 mg/kg or 50 mg/m

2

i.m. without folinic acid) [

7]. Current

regimens of MTX for the treatment of EP reduce the total MTX dose that patients

receive compared to other indications such as chemotherapy. Therefore, the incidence

of therapy-related side effects was low [

8].

Most side effects of MTX are minor, such as nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, and

diarrhea, and have rarely been reported to be linked to pancreatitis.

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common disease that affects the digestive system. AP is

diagnosed on the basis on the fulfillment of 2 out of 3 of the following criteria :

clinical (upper abdominal pain), laboratory (serum amylase or lipase

>3× upper limit of normal) and/or imaging (CT, MRI, ultrasonography)

criteria [

9]. Various etiologies of AP, most

of which are due to gallstones. Other common causes of pancreatitis are alcohol

consumption, hyperlipidemia, hypercalcemia, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, drugs and

toxins, which may also be idiopathic or traumatic [

10]. The management of AP involves providing active treatment, including

fluid resuscitation, nutritional support, analgesics, and etiological treatment

[

11]. At present, three cases of

MTX-induced pancreatitis have been reported [

12,

13]. We report a case of a

40-year-old woman who underwent MTX therapy for an unruptured EP and developed

AP.

Go to :

Case

A 40-year-old gravida 2, para 1 woman visited the emergency department with upper

abdominal pain. She had nausea and a low-grade fever, with a maximum temperature of

37.8°C. Abdominal examination revealed severe tenderness in the epigastric

area, and both the right and left upper quadrants without muscle guarding or rebound

tenderness.

The patient did not consume any other medications or alcohol. She had visited another

hospital four weeks ago because of lower abdominal pain and was diagnosed with a

left tubal EP. On that day, her total serum hCG level was 23,544 mIU/mL. She had

been treated with a single dose of MTX (99.1 mg), intramuscularly four weeks before

her visit to this hospital. A week after MTX injection, her total serum hCG level

was 13,166 mIU/mL, and 4,620 mIU/mL after two weeks. Three weeks after the injection

the total serum hCG level was 1,400 mIU/mL, and transvaginal sonography revealed a

decrease in the size of the left adnexal mass.

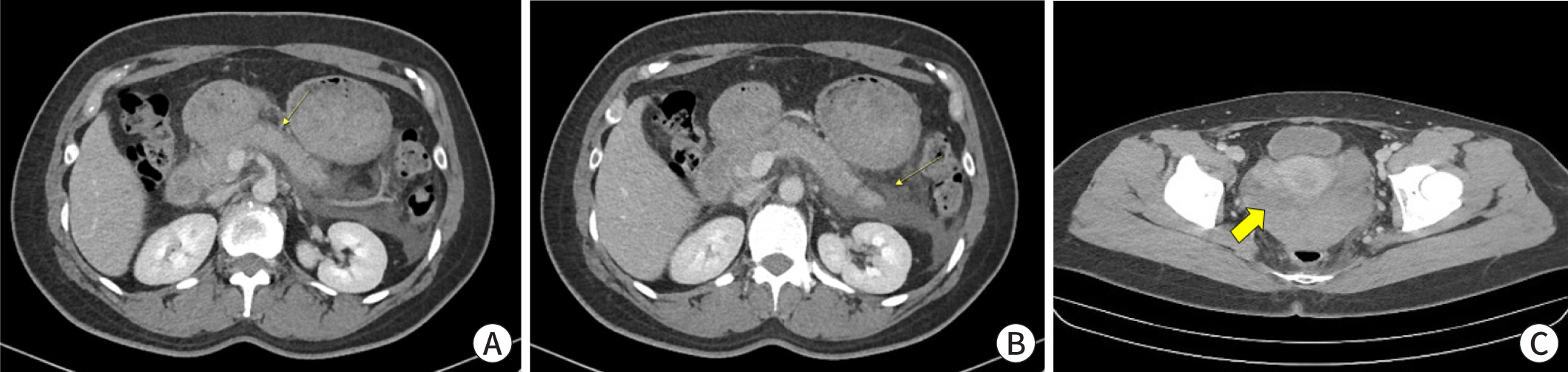

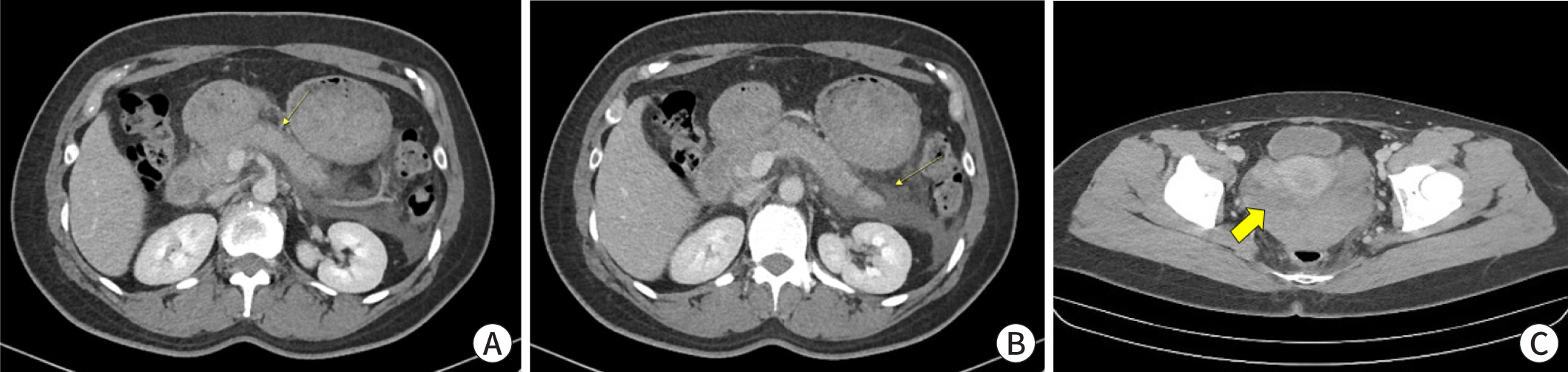

Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scan showed diffuse acute interstitial

edematous pancreatitis with peripancreatic fluid collection and infiltration (

Fig. 1A) and acute hematoma in the cul-de-sac

without active bleeding (

Fig. 1C). Upper

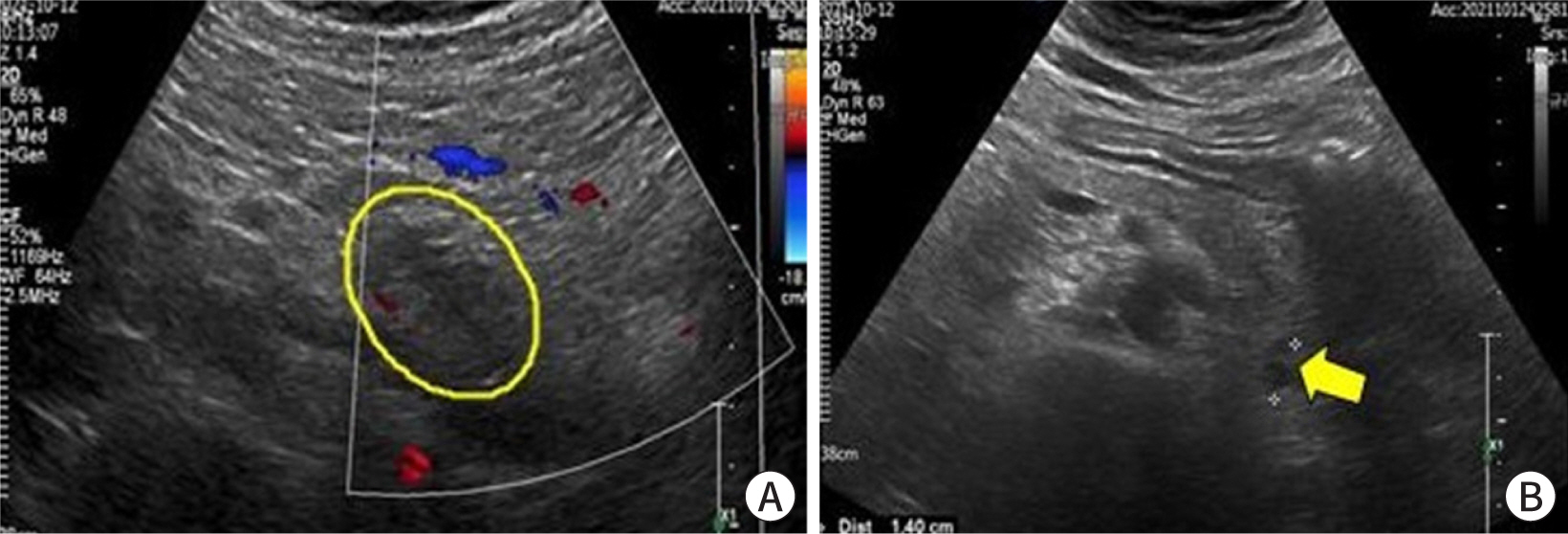

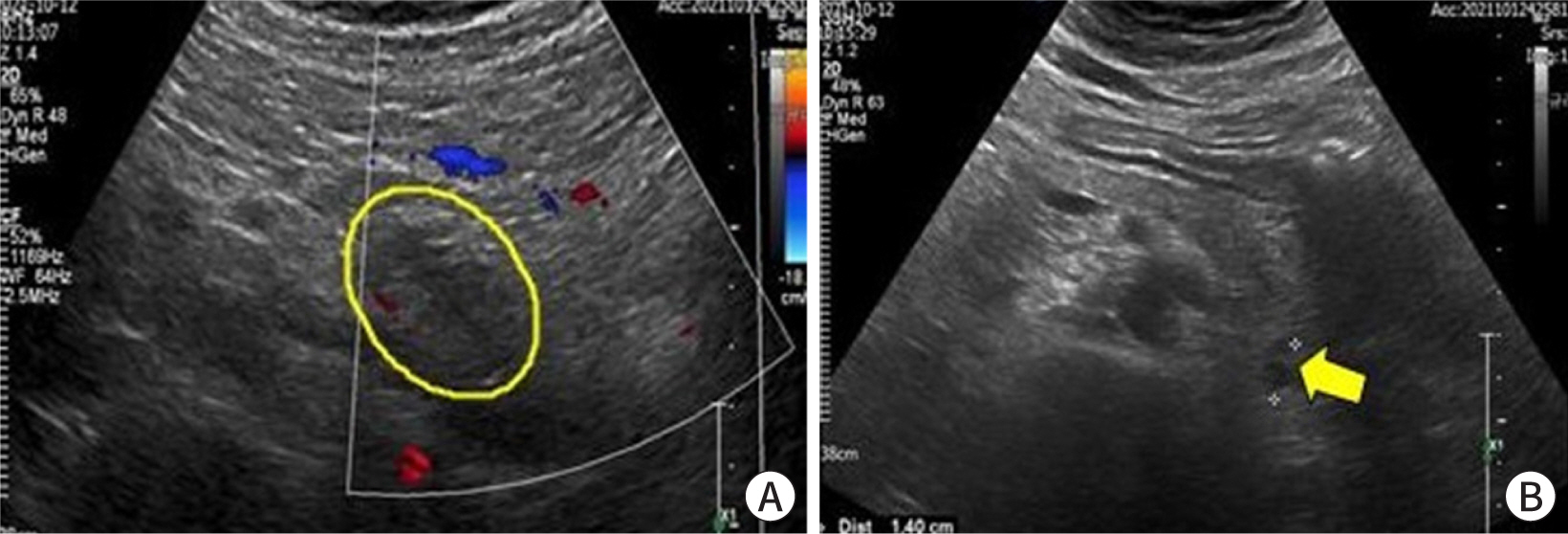

abdominal ultrasonography findings were consistent with that of AP (

Fig. 2A,

2B).

| Fig. 1. Abdominal pelvic CT scan on admission day. (A) Pancreatic parenchyma

enhancement by intravenous contrast agent. Acute inflammation of the

pancreatic parenchyma and peripancreatic tissue, with stranding of the

surrounding fat. (B) Acute peripancreatic fluid collection in the left

anterior pararenal space. (C) Acute hematoma (arrow) in the cul-de-sac

without active bleeding.

|

| Fig. 2. Abdominal sonogram on admission day. (A) Enlarged and swollen of acute

pancreatitis (circle) with peripancreatic fluid collection. (B) 1.4 cm

anechoic lesion (arrow) around the pancreatic tail, with probable loculated

peripancreatic fluid collection.

|

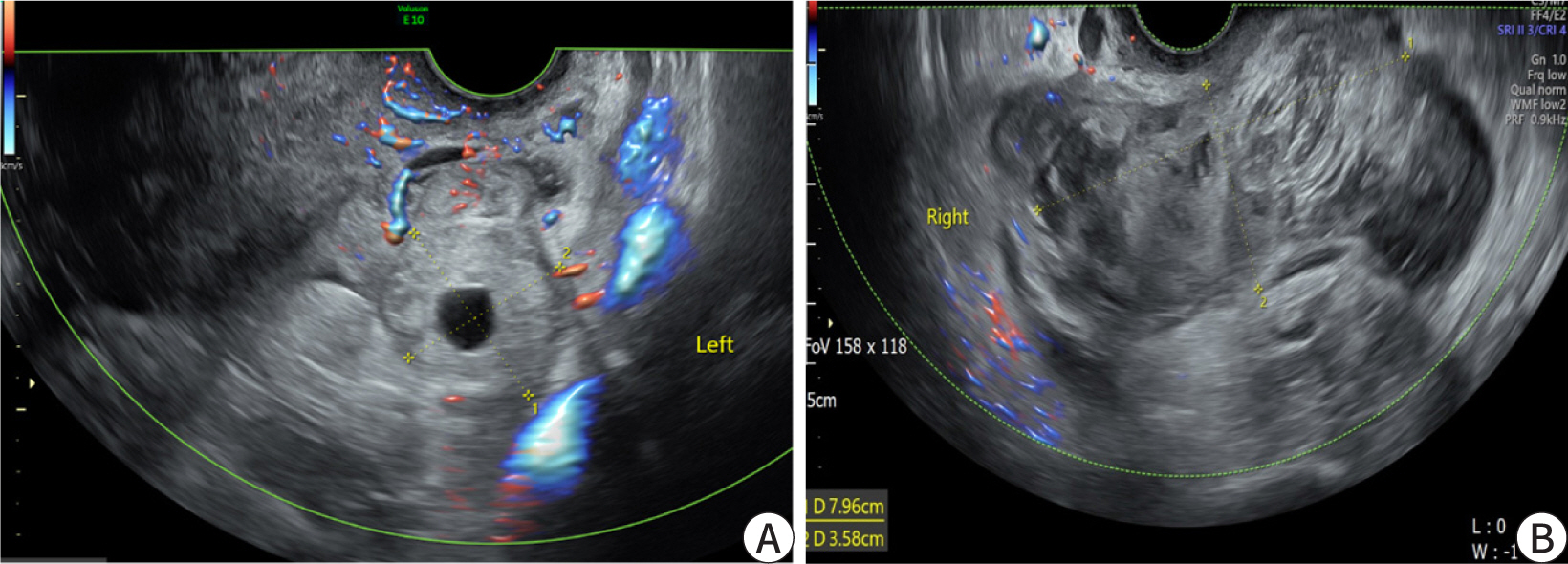

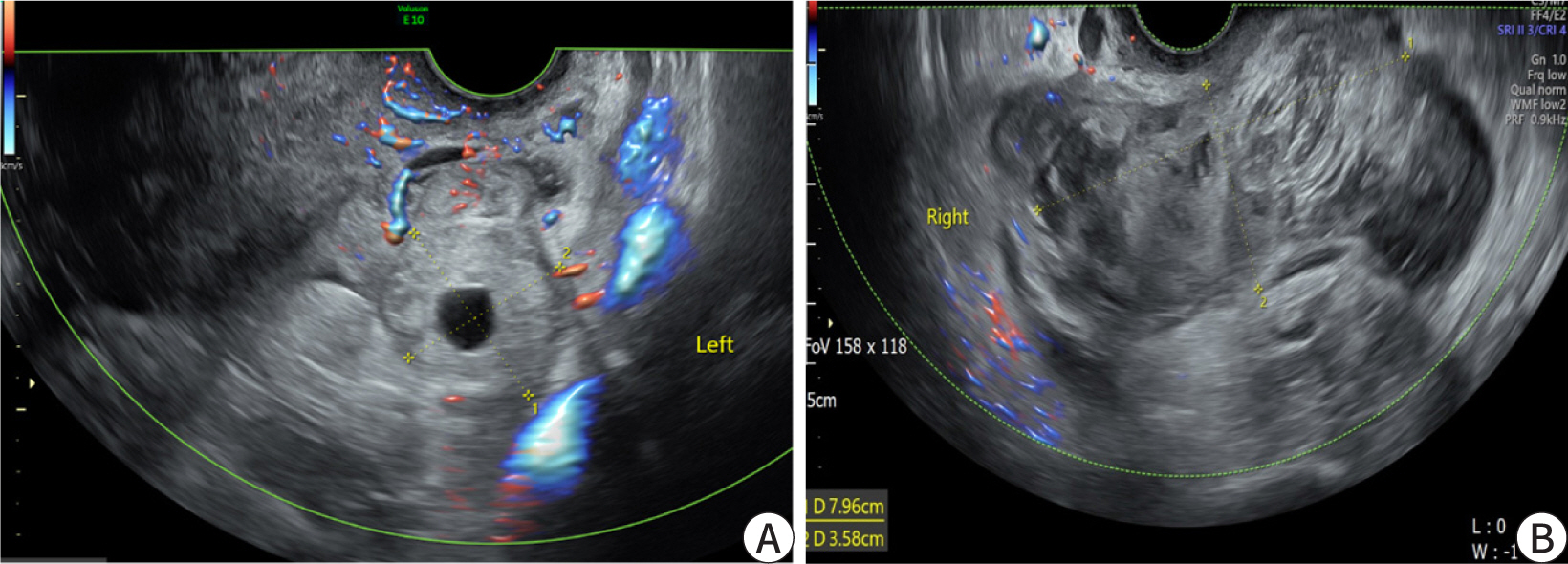

Transvaginal ultrasonography revealed an empty uterus with 2.53 mm thick endometrium

and a probable ectopic mass at the left adnexa, measuring 3.15 cm in the largest

diameter, with degenerated gestational sac inside, but no fetal pole (

Fig. 3A). A hematoma sized 7.9×3.5

cm

2 was noted in the posterior cul-de-sac (

Fig. 3B).

| Fig. 3. Transvaginal sonogram on admission. (A) Coronal view of the left adnexa.

The thick-walled left adnexa cystic structure, separate from the ovary,

called ‘tubal ring sign’, which show unruptured tubal ectopic

pregnancy. (B) Hematoma, sized 7.9×3.5 cm2, in posterior

cul-de-sac.

|

According to the laboratory investigations, hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference

range, 12.0–16.0 g/dL), WBC was 8,400 μL (4,000–10,000

μL), platelet counts were 349,000 μL (150,000–450,000

μL), total bilirubin was 0.38 mg/dL (≤1.2 mg/dL) with direct bilirubin

level of 0.14 mg/dL (≤0.25 mg/dL), AST was 15 IU/L (≤33 IU/L), ALT was

8 IU/L (≤33 IU/L), ALP was 87 IU/L (30–120 IU/L), total cholesterol

was 193 mg/dL (≤200 mg/dL), which were within the normal range. The enzymes

showed elevated levels: LDH 282 IU/L (135–214 IU/L), amylase 1,864 IU/L

(28–100 IU/L), lipase 4,394 IU/L (13–60 IU/L), CRP 0.97 mg/dL

(≤0.5 mg/dL), triglyceride 178 mg/dL (28–150 mg/dL), fibrinogen 458.1

mg/dL (180–350 mg/dL), FDP 13.7 μg/mL (≤5 μg/mL),

D-dimer 5.44 mg/L (≤0.59 mg/L). HCG was detected on urine examination, and

the total hCG level on admission was 1,289.0 mIU/mL. Considering her clinical

manifestations, laboratory tests, CT scan and abdominal ultrasound findings, the

diagnosis of AP was confirmed.

The patient was admitted to the hospital and received conservative medical management

with analgesia, hydration and fasting. She received gabexate 20 mg intravenously

daily for five days and 100,000 units injection units of ulinastatin intravenously

per daily for two days. Those gabexate mesylate and ulinastatin are protease

inhibitors, which are accepted as a potential treatment to inhibit the pancreatic

inflammation in AP [

14].

She was administered ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 12 h intravenously for five days

during her hospitalization.

On fourth day after hospitalization, repeated measurements of her amylase and lipase

levels were within normal limits: amylase 75 IU/L (28–100 IU/L), lipase 35

U/L (13–60 IU/L); and the total hCG level decreased to 762.0 mIU/mL. The

patient’s symptoms continued to improve during her course of hospitalization.

The patient was discharged with oral ciprofloxacin 500 mg per 12 h for discharge

medication, on the 6th day of admission after significant clinical and laboratory

improvement. The patient presented with complete resolution of symptoms and

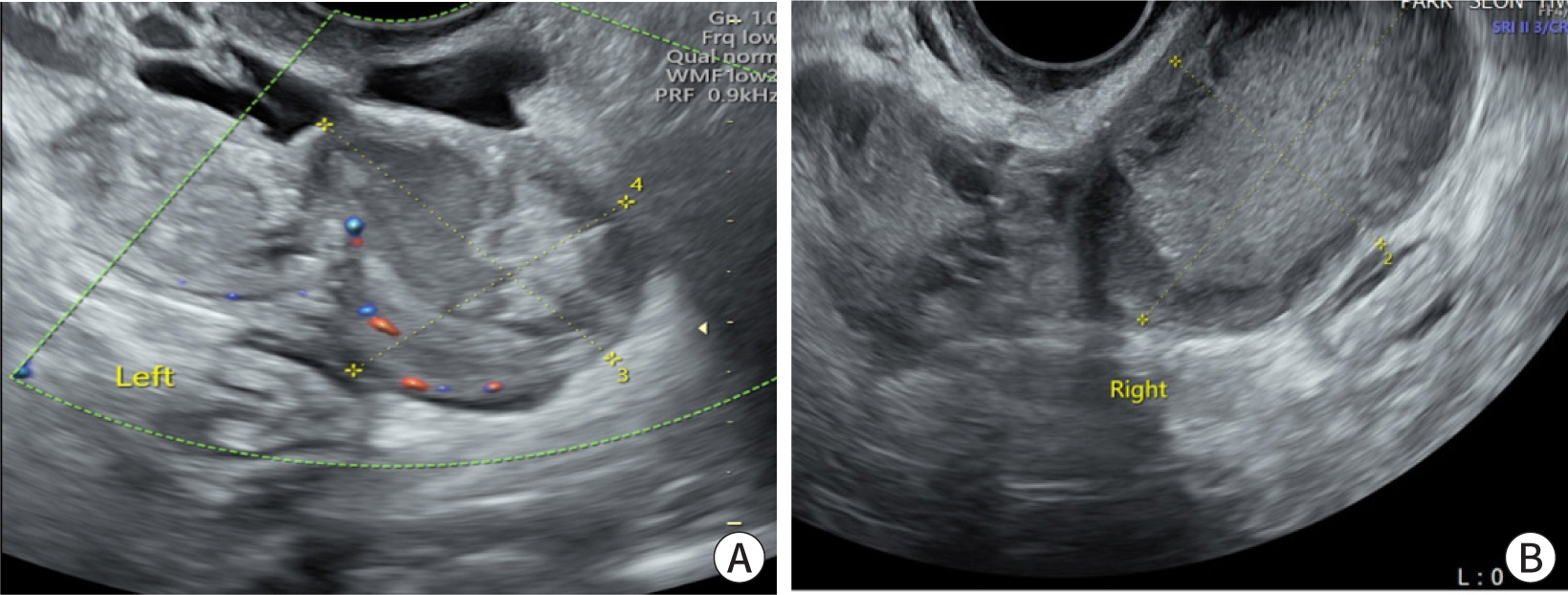

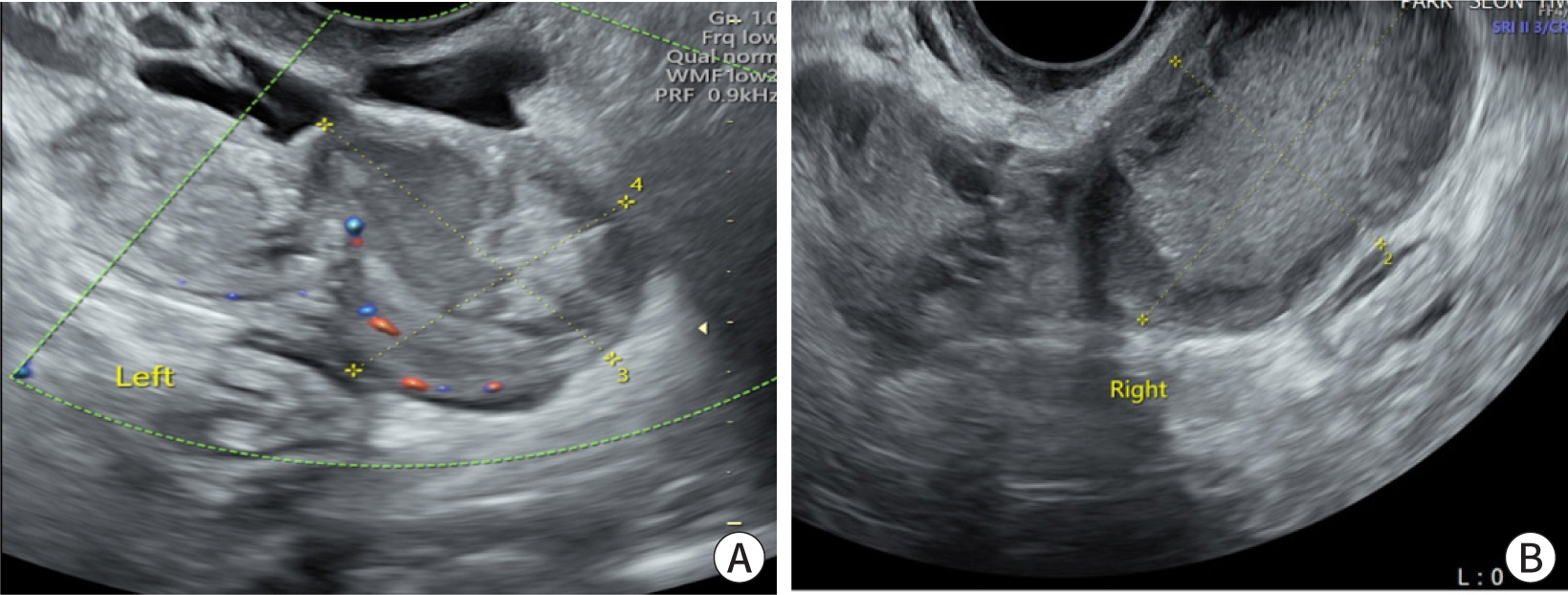

biochemical results during ambulatory follow-up. The follow-up transvaginal

sonography revealed a decrease in the size of the hematoma and left adnexa mass

(

Fig. 4A,

4B).

| Fig. 4. Follow-up transvaginal sonogram after treatment. (A) Complex echoic,

irregular shaped left adnexa mass, sized 3.2×2.7 cm2.

Previously tubal ring sign disappeared and the total size of the mass was

decreased. (B) A 5.0×3.1 cm2 hematoma in the posterior

cul-de-sac.

|

Go to :

Discussion

We report a rare case of MTX-induced pancreatitis in a patient with EP and treated

with MTX. EP may be life threatening, and further treatment is determined based on

the patient’s hemodynamic status, size of the ectopic mass, and level of

beta-hCG. Medical treatment primarily uses the regimen of MTX [

1]. Current regimens of MTX reduce the total MTX dose that

patients receive compared with other indications such as chemotherapy [

4]. Therefore, the incidence of therapy-related

side effects is low, and most are minor side effects such as nausea, vomiting,

stomatitis, and diarrhea [

1]. Cases of

MTX-induced pancreatitis are rare, and previous studies have reported a case of a

16-year-old girl with systemic lupus erythematosus acute necrotizing pancreatitis

was attributed to a combination regimen involving MTX [

12]. Another case report is of a 36-year-old woman who received

MTX along with etoposide, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine for

suspected hydatidiform mole developed AP. Moreover, another case of a 10-year-old

girl with acute lymphatic leukemia who was treated with vincristine, daunorubicin,

L-asparaginase, intrathecal MTX, cyclophosphamide, and oral 6 MP and had MTX-induced

pancreatitis has been reported [

13]. However,

AP after using MTX for the treatment of EP was not found in previously published

studies and this report has very important implication that we should consider other

differential diagnosis when we evaluate the patient suffering severe abdominal pain,

treated with MTX due to EP. Cramp abdominal pain which is self-limiting and

controlled with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent is common side effect during

MTX for an EP [

15]. Also, If a patient with

EP experiences severe abdominal pain after MTX therapy, clinicians would mostly

suspect ectopic mass rupture, which will necessitate surgical treatment, and other

differential diagnosis may be overlooked. However, if there is no evidence of an

ectopic mass rupture, suspicion of other causes, laboratory tests, and imaging must

be performed based on the clinical manifestations.

The side effects of MTX may be overlooked in the clinical settings of EP. If a

patient with EP experiences abdominal pain after MTX therapy, clinicians would

mostly suspect ectopic mass rupture, which will necessitate surgical treatment.

However, if there is no evidence of an ectopic mass rupture, suspicion of other

causes, laboratory tests, and imaging must be performed based on the clinical

manifestations.

This case report has some limitations. For the diagnosis of an adverse drug reaction,

the time relationship between the use of the drug and the occurrence of the reaction

should be assessed. In addition, drug rechallenge should be considered [

16]. However, since the patient received a

single dose of MTX, there was no chance of rechallenge with drug.

Second, MTX has rarely been reported to be associated with the pancreatitis, and its

possible etiology is unknown. Therefore, future studies and case reports are

required in this area.

Although MTX-induced pancreatitis is a rare complication, it is important for

clinicians to be aware of all possible complications of MTX because it is a widely

used medical treatment for EP. We hope that this may aid in the evaluation of

patients with severe abdominal pain after using MTX therapy.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download