This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background

Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) experience both motor and non-motor symptoms, including dysphagia. Although PD is closely associated with dysphagia, the prevalence or risk of dysphagia in PD is unclear, especially in Asian countries.

Methods

The prevalence of PD and dysphagia with PD in the general population was analyzed using the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database. The prevalence per 100,000 persons of PD and dysphagia with PD from 2006 to 2015 was analyzed in the general population aged ≥ 40 years. Patients newly diagnosed with PD between 2010 and 2015 were compared with those without PD.

Results

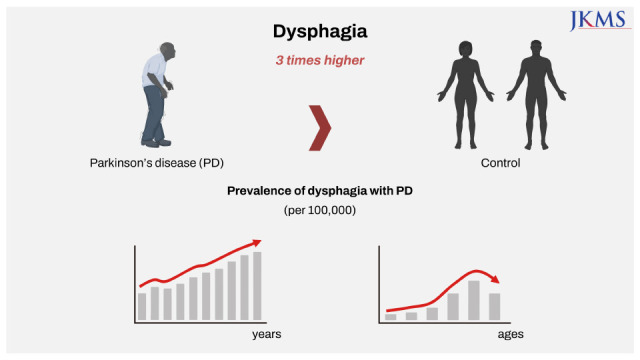

The prevalence of PD and dysphagia in patients with PD increased continuously during the study period and was highest in the ninth decade of life. The percentage of patients with dysphagia in patients with PD increased with age. Patients with PD showed an adjusted hazard ratio of 3.132 (2.955–3.320) for dysphagia compared to those without PD.

Conclusion

This nationwide study showed increasing trends in the prevalence of PD and dysphagia among patients with PD in Korea between 2006 and 2015. The risk of dysphagia was three times higher in patients with PD than that in those without PD, highlighting the importance of providing particular attention.

Keywords: Dysphagia, Parkinson’s Disease, Hazard Ratio, Prevalence, Population-Based Study

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease primarily affecting older adults. The prevalence of PD increases with age, and the population of patients with PD is expected to increase as a consequence of global aging.

1 Although motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor are important for the diagnosis of PD, non-motor symptoms such as fatigue, depression, constipation, and dysphagia are also frequently observed in these patients.

23

Dysphagia, i.e., swallowing dysfunction, refers to the difficulty in making or moving the alimentary bolus to the stomach safely. The overall prevalence of dysphagia is more than 30% in community-dwelling older adults.

4 It is closely associated with malnutrition, longer hospital stays, poor quality of life, and increased mortality.

5 PD is one of the important etiologies of dysphagia, showing a pooled prevalence of 35% and up to 82% using subjective measures and objective measures, respectively.

6 However, there is a dearth of data on the prevalence or risk of dysphagia in patients with PD, especially in Asian countries.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of PD and dysphagia and estimate the risk of dysphagia in patients with PD compared to that in those without PD in Korea using nationwide health insurance data.

METHODS

Data source

Data were obtained from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database. The Korean NHIS is an obligatory social health insurance that provides health care and medical aid in Korea. All data from medical service claims records, including diagnostic codes based on the International Classification of Disease 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), and sociodemographic information were collected in the NHIS database. Therefore, the prevalence in the general population could be obtained.

PD and dysphagia

PD was defined using the ICD-10-CM code for PD (G20) and a registration code (V124) that was given for rare intractable diseases in Korea.

7 The claims data of January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2015 were collected. Patients aged < 40 years were excluded.

Patients were defined operationally as having dysphagia if they met at least one of the following conditions: 1) presence of the ICD-10-CM code for dysphagia (R13), 2) records of at least two swallowing therapy sessions (MX141) within 1 month, 3) records of at least two instrumental swallowing tests (E7011, E7012), such as videofluoroscopic swallowing studies and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing within 3 months, 4) records of nasogastric tube insertions (Q2621, Q2622) at least twice within 3 months, or 5) presence of procedure claim codes (M6730, Q2612) for percutaneous gastrostomy.

Study population

Patients newly diagnosed with PD from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2015, without history of dysphagia were compared to a 1:1 age- and sex-matched population without PD or dysphagia to compare the incidence of dysphagia between patients with and without PD. Patients < 40 years old were excluded. The participants were followed up until December 31, 2016 (the follow-up period ranged from 1 to 7 years).

Covariate data

Data on sociodemographic factors including age, sex, and income were collected. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was defined based on the diagnostic codes J41–J44. Stroke was defined based on ICD-10-CM codes I63 and I64 with brain imaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) during hospital admission. Dementia was defined based on ICD-10-CM codes F00–F03, G30–G31, G231, G310, G318, and F107. The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score was used as an indicator for the overall disease burden, which was calculated by reviewing the patients’ ICD-10-CM codes. The CCI scores were categorized as 0, 1, and ≥ 2. The severity of disability was graded into six degrees according to the National Disability Registry System, mainly based on the Modified Barthel Index.

8 Grade 1 represents the most severe disability, whereas grade 6 represents the least severe disability (

Supplementary Table 1). Disability grades were categorized as none, 1–3, and 4–6.

Statistical analyses

The crude annual prevalence per 100,000 persons for PD and dysphagia with PD in the general population aged ≥ 40 years and the proportion of patients with dysphagia among those with PD were calculated. A comparative analysis was conducted between patients newly diagnosed with PD between 2010 and 2015 and age- and sex-matched controls. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables. Cox regression analysis was used to evaluate the hazard ratios for dysphagia in patients with PD with adjustments for age, sex, income quartiles, COPD, stroke, dementia, CCI, and disability grade.

Ethics statement

This study was exempted from review by Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Institutional Review Board (X-1805-471-902). The requirement for informed consent was waived because the data used in this study were fully anonymized.

RESULTS

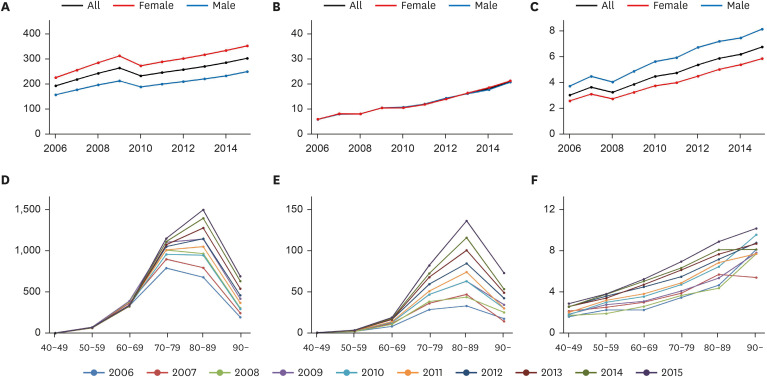

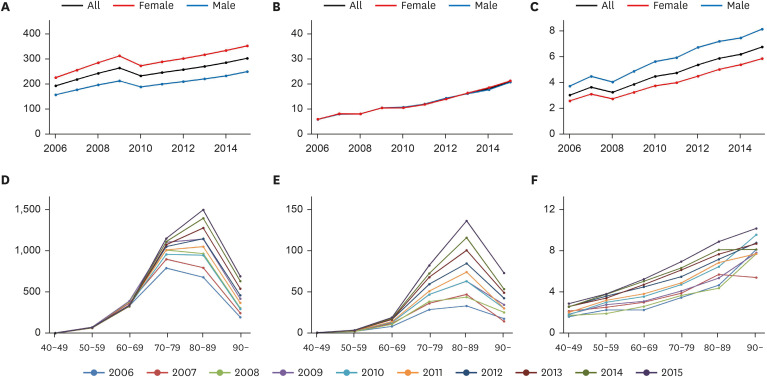

The prevalence per 100,000 persons of PD and dysphagia with PD is presented in

Fig. 1A and B and

Supplementary Table 2. The prevalence of PD increased continuously during the study period, except in 2010. Women showed a higher prevalence of PD than men. Furthermore, the prevalence of dysphagia in patients with PD increased during the study period. In addition, the percentage of dysphagia among patients with PD increased; however, men showed a higher percentage of dysphagia than women (

Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1

The prevalence (per 100,000 persons) of Parkinson’s disease (A) and Parkinson’s disease with dysphagia (B), and the percentage of patients with dysphagia among those with Parkinson’s disease (C) from 2006 to 2015. The prevalence (per 100,000 persons) of Parkinson’s disease (D) and Parkinson’s disease with dysphagia (E), and the percentage of patients with dysphagia among those with Parkinson’s disease (F) by age group.

The prevalence (per 100,000 persons) of PD and dysphagia in patients with PD was highest in the ninth decade of life (

Fig. 1D and E). However, the percentage of patients with dysphagia among patients with PD increased continuously with age (

Fig. 1F).

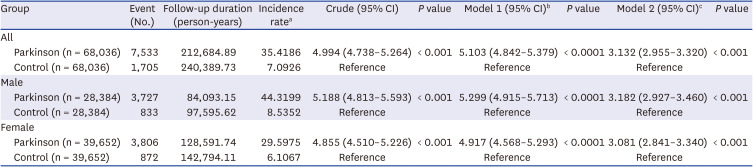

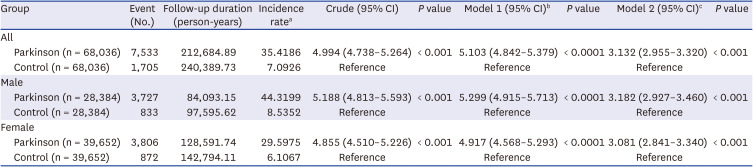

Patients diagnosed with PD between 2010 to 2015 (n = 68,036) were compared with those without PD (n = 68,036). Despite matching age and sex between the two groups, income, COPD, stroke, dementia, CCI, and disability grade differed significantly between them (

Supplementary Table 3). Patients with PD showed a crude hazard ratio of 4.994 (95% confidence interval, 4.738–5.264) and an adjusted hazard ratio of 3.132 (2.955–3.320) for dysphagia, compared to those without PD (

Table 1). The risk of dysphagia in patients with PD was similar in men and women.

Table 1

Hazard ratios for dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease

|

Group |

Event (No.) |

Follow-up duration (person-years) |

Incidence ratea

|

Crude (95% CI) |

P value |

Model 1 (95% CI)b

|

P value |

Model 2 (95% CI)c

|

P value |

|

All |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parkinson (n = 68,036) |

7,533 |

212,684.89 |

35.4186 |

4.994 (4.738–5.264) |

< 0.001 |

5.103 (4.842–5.379) |

< 0.0001 |

3.132 (2.955–3.320) |

< 0.001 |

|

Control (n = 68,036) |

1,705 |

240,389.73 |

7.0926 |

Reference |

|

Reference |

|

Reference |

|

|

Male |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parkinson (n = 28,384) |

3,727 |

84,093.15 |

44.3199 |

5.188 (4.813–5.593) |

< 0.001 |

5.299 (4.915–5.713) |

< 0.0001 |

3.182 (2.927–3.460) |

< 0.001 |

|

Control (n = 28,384) |

833 |

97,595.62 |

8.5352 |

Reference |

|

Reference |

|

Reference |

|

|

Female |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parkinson (n = 39,652) |

3,806 |

128,591.74 |

29.5975 |

4.855 (4.510–5.226) |

< 0.001 |

4.917 (4.568–5.293) |

< 0.0001 |

3.081 (2.841–3.340) |

< 0.001 |

|

Control (n = 39,652) |

872 |

142,794.11 |

6.1067 |

Reference |

|

Reference |

|

Reference |

|

DISCUSSION

This nationwide study conducted in an Asian country showed increasing trends in PD and PD with dysphagia from 2006 to 2015. The prevalence of PD and PD with dysphagia was the highest in the ninth decade of life; however, the prevalence of PD with dysphagia per 100,000 persons continuously increased with age.

After adjusting for possible confounders, PD increased the risk of dysphagia by approximately three times. Dysphagia in patients with PD could be explained by extrapyramidal dysfunction caused by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons.

9 Lewy bodies or the alpha-synuclein pathology may also be involved in the pathogenesis of dysphagia.

10 As for the treatment of dysphagia, voice therapy could be considered as maximum phonation time was significantly correlated with swallowing function.

11 In addition, various approaches, such as compensation strategies, swallowing maneuvers, postural treatment, muscular training, and electrical stimulation, could improve the degenerative function of swallowing and quality of life.

12

The prevalence of dysphagia in patients with PD showed an increasing trend similar to that of the prevalence of PD, ranging from 3.1% in 2006 to 6.8% in 2015. However, previous studies have reported a much higher prevalence, even more than 80%,

6 although definitions and assessment tools differed among studies. Considering that all patients who had a diagnostic code for PD were included, our study may have involved patients with earlier stage of PD than those in previous studies. However, dysphagia usually develops in the late stage of PD.

13 Additionally, our operational definition of dysphagia may have influenced the finding of low prevalence. Claim codes related to diagnosis, treatment, and intervention related to dysphagia were used to define dysphagia. Therefore, only patients with dysphagia who needed medical attention (such as more than two sessions of swallowing therapy, evaluation, and percutaneous gastrostomy) were included in the analysis. Although our definition of dysphagia did not reflect the results of subjective or objective measures for dysphagia, future studies using nationwide insurance data could be conducted to investigate the epidemiology of dysphagia using our methodology.

This study showed that the prevalence of PD was higher in women than that in men. Previous studies in Western countries showed a male preponderance in PD,

14 whereas those in Asian countries showed a female preponderance.

1516 The reasons for this are still unclear; however, genetic susceptibilities and different risk or preventive factors such as dietary deficiencies, smoking, and coffee consumption in the Asian population could be suggested. In contrast, the percentage of patients with dysphagia in patients with PD was higher in men. A previous study on 119 patients with PD showed a similar result, in that the male sex was associated with a high risk for dysphagia as compared to the female sex.

17

This study has several limitations; first, a possibility of misclassification, considering that insurance claims data were used, as PD was defined using claim codes for the diagnosis. Dysphagia was defined operationally using claim codes for diagnosis, treatment, and interventions related to dysphagia. Second, the stage of PD, such as by using the Hoehn and Yahr scale score or disease duration, was not identified. Third, other confounding factors may influence the risk of dysphagia in patients with PD.

In conclusion, increasing trends in the prevalence of PD and PD with dysphagia were observed in Korea from 2006 to 2015. The prevalence of PD and dysphagia with PD was highest in the ninth decade of life, whereas the percentage of dysphagia among patients with PD continuously increased with age. The risk of dysphagia was three times higher in patients with PD than that in those without PD, after adjusting for possible confounders. Therefore, in geriatric healthcare, special attention is required for the adequate screening and management of dysphagia in PD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study used the National Health Information Database (NHIS-2019-1-100) made by the Korean NHIS. The author(s) declare no conflict of interest with NHIS and would like to thank the NHIS for cooperation.

References

1. Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TD. The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014; 29(13):1583–1590. PMID:

24976103.

2. Schapira AH, Chaudhuri KR, Jenner P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017; 18(7):435–450. PMID:

28592904.

3. Choi JH, Kim JM, Yang HK, Lee HJ, Shin CM, Jeong SJ, et al. Clinical perspectives of Parkinson’s disease for ophthalmologists, otorhinolaryngologists, cardiologists, dentists, gastroenterologists, urologists, physiatrists, and psychiatrists. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(28):e230. PMID:

32686370.

4. Yang EJ, Kim MH, Lim JY, Paik NJ. Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in a community-based elderly cohort: the Korean longitudinal study on health and aging. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28(10):1534–1539. PMID:

24133362.

5. Altman KW, Yu GP, Schaefer SD. Consequence of dysphagia in the hospitalized patient: impact on prognosis and hospital resources. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010; 136(8):784–789. PMID:

20713754.

6. Kalf JG, de Swart BJ, Bloem BR, Munneke M. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012; 18(4):311–315. PMID:

22137459.

7. Yoon SY, Shin J, Chang JS, Lee SC, Kim YW. Effects of socioeconomic status on mortality after Parkinson’s disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study in Korean populations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020; 80:206–211. PMID:

33129703.

8. Jung I, Kwon H, Park SE, Han KD, Park YG, Rhee EJ, et al. The prevalence and risk of type 2 diabetes in adults with disabilities in Korea. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2020; 35(3):552–561. PMID:

32693567.

9. Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006; 5(3):235–245. PMID:

16488379.

10. Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003; 24(2):197–211. PMID:

12498954.

11. Ko EJ, Chae M, Cho SR. Relationship between swallowing function and maximum phonation time in patients with parkinsonism. Ann Rehabil Med. 2018; 42(3):425–432. PMID:

29961740.

12. López-Liria R, Parra-Egeda J, Vega-Ramírez FA, Aguilar-Parra JM, Trigueros-Ramos R, Morales-Gázquez MJ, et al. Treatment of dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(11):4104. PMID:

32526840.

13. Kwon M, Lee JH. Oro-pharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease and related movement disorders. J Mov Disord. 2019; 12(3):152–160. PMID:

31556260.

14. Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Time trends in the incidence of Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2016; 73(8):981–989. PMID:

27323276.

15. Yamawaki M, Kusumi M, Kowa H, Nakashima K. Changes in prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’s disease in Japan during a quarter of a century. Neuroepidemiology. 2009; 32(4):263–269. PMID:

19209006.

16. Park JH, Kim DH, Kwon DY, Choi M, Kim S, Jung JH, et al. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s disease in Korea: a nationwide, population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2019; 19(1):320. PMID:

31752705.

17. Nienstedt JC, Bihler M, Niessen A, Plaetke R, Pötter-Nerger M, Gerloff C, et al. Predictive clinical factors for penetration and aspiration in Parkinson’s disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019; 31(3):e13524. PMID:

30548367.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 2

Prevalence per 100,000 persons of Parkinson’s disease and dysphagia in patients with Parkinson’s disease

jkms-38-e114-s002.doc

Supplementary Table 3

Clinical characteristics between patients with Parkinson’s disease and age- and sex- matched controls

jkms-38-e114-s003.doc

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download