Abstract

Acute cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection occurs commonly in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients, but is usually asymptomatic in the latter. Vascular events associated with acute CMV infection have been described, but are rare. Hence, such events are rarely reported in the literature. We report a case of pulmonary embolism secondary to acute CMV colitis in an immunocompetent 78-year-old man. The patient presented with fever and diarrhea. Colonic ulcers were diagnosed based on colonoscopy findings, and CMV was the proven etiology on pathological examination. The patient subsequently experienced acute respiratory failure. Pulmonary embolism was diagnosed based on the chest radiography and computed tomography findings. A diagnosis of acute CMV colitis complicated by pulmonary embolism was made. The patient was successfully treated with intravenous administration of unfractionated heparin and intravenous ganciclovir.

Acute cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is common in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients worldwide.12 The infection is often asymptomatic. Symptoms, when they occur, include fever, cervical lymphadenitis, and arthralgia.3 Rarely, acute CMV infection may be complicated by pneumonia, colitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, or hemolytic anemia.4 Vascular events caused by acute CMV infection, including thrombosis of the venous or arterial vascular system, are rarely reported in the English literature. We report a case of acute CMV colitis in an immunocompetent adult that was complicated by vascular thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Further, we present a review of the literature regarding the association between vascular events and CMV infection in immunocompetent patients.

A 78-year-old man was referred to our emergency department with a 3-day history of diarrhea and fever. He had no recent travel history, did not use steroids, and had not experienced recent trauma. There was no history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. He used medication for hypertension and diabetes mellitus, both of which were well controlled. On admission, his vital signs were: body temperature, 38.8℃; blood pressure, 145/85 mmHg; respiratory rate, 18/min; and pulse rate, 90/min. On physical examination, his pulse was regular and he had no cardiac murmurs, his chest was clear without signs of respiratory distress, and his abdomen was soft with hyperactive bowel sounds. He had no peripheral edema. Laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 8,270/mm3 (normal: 3,990−10,500/mm3), a platelet count of 199,000/mm3 (normal: 140,000−450,000×/mm3), a prothrombin time of 14.10 seconds (control: 11.16 seconds), an INR of 1.21, an activated partial thromboplastin time of 26.0 seconds (control: 27.4 seconds), and CRP level of 16.7 mg/dL (normal: <0.8 mg/dL). A coagulation profile, including protein C (80%, normal: 70%−140%), protein S (75%, normal: 60%−130%) and anti-thrombin III (95%, normal: 75%−125%), was normal. Other laboratory test results were unremarkable. Colonoscopy demonstrated multiple giant ulcers with skip lesions in the distal colon, sparing the rectum (Fig. 1). Multiple forceps-biopsy tissue samples, taken from the coloniculcers, were sent for pathological examination.

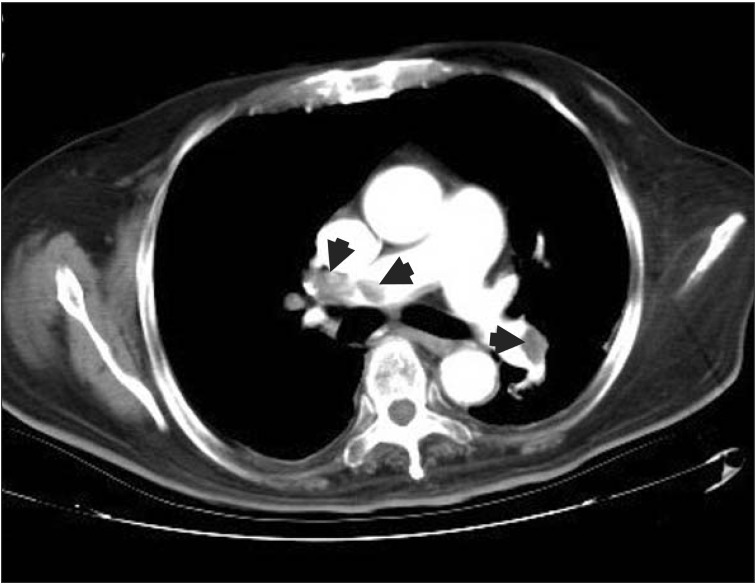

However, 5 days post-colonoscopy, the patient experienced dyspnea and severe hypoxemia, necessitating emergent endotracheal intubation and ventilation. A chest radiograph obtained post-intubation revealed an engorged main pulmonary trunk with an abrupt cutoff of pulmonary vascularity in the distal portions bilaterally, indicative of the "Westermark sign" (Fig. 2, arrows). Subsequently, a CT scan of the chest was performed that showed several filling defects within the pulmonary trunk and main pulmonary arteries (Fig. 3). The patient was thus diagnosed as having pulmonary embolism.

Histological evaluation of the colonic biopsy specimens revealed cytomegalic cells with densely staining nuclei and intranuclear inclusion bodies in the epithelium (Fig. 4A, arrows). These epithelial cells were positive for monoclonal anti-CMV antibody on immunohistochemical analysis, indicative of CMV infection (Fig. 4B, arrows). Based on these pathological features, a diagnosis of CMV colitis was made.

The patient had no obvious risk factors for thrombosis, and had no family history of coagulopathy. Therefore, the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism secondary to acute CMV colitis was considered. The patient recovered after receiving intravenous ganciclovir and unfractionated heparin. Follow-up CT scan of the patient's chest showed complete resolution of the pulmonary emboli.

Acute CMV infection in immunocompetent patients is common worldwide, with seroprevalence rates ranging from 40% to 100%, depending on country, socio-economic conditions, and age.1 Colitis is the most common manifestation of severe CMV infection.2 Patients with CMV colitis are generally asymptomatic; if symptomatic, they may present with diarrhea, fever, bleeding, abdominal pain, and perforation. 4 Vascular events are a very rare manifestation of severe CMV infection in immunocompetent individuals.2 These vascular events include thrombosis of the portal, superior mesenteric, or splenic vein; cerebral venous thrombosis; deep vein thrombosis; and life-threatening pulmonary embolism. 567 Vascular complications may be discovered only several weeks after the initial diagnosis of CMV infection. However, Abgueguen et al. proposed that venous thrombosis in immunocompetent patients with CMV infection may not be as rare as previously reported.8 Although the pathogenesis of CMV-induced vascular events is unknown, several mechanisms have been postulated, including direct damage to endothelial cells, increased levels of hemostatic indicators, induction of smooth muscle proliferation, enhanced platelet-derived growth factor production, and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.91011

Vascular thrombosis in immunocompetent patients is usually associated with predisposing factors such as heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation, presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, heterozygous prothrombin gene mutation, protein C and/or protein S deficiency, or oral contraceptive use.12 In contrast, this patient had no family history of coagulopathy, was not bed-ridden, and had no other risk-factors for thrombosis. It is, therefore, likely that CMV infection was the precipitating factor for pulmonary embolism.

In the diagnosis of vascular events caused by CMV infection, Doppler ultrasound and CT scanning are the most useful diagnostic modalities.6 Treatment of CMV-associated pulmonary embolism includes immediate administration of antiviral agents and anticoagulants. Advanced age, male gender, presence of immune-modulating comorbidities, and need for surgical intervention all negatively influence survival.13 Although the cost-effectiveness of investigating for acute CMV infection in patients presenting with thrombosis has not yet been established, we believe that serum samples for CMV infection should be obtained and endoscopic examination should be considered in patients with idiopathic thrombosis.

In conclusion, although pulmonary embolism caused by acute CMV colitis in immunocompetent patients is extremely rare, it should be considered in patients who present with severe respiratory symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an immunocompetent patient with acute CMV colitis complicated by vascular thrombosis with pulmonary embolism in which no other obvious underlying predisposing factor for thrombosis was identified.

References

1. Staras SA, Dollard SC, Radford KW, Flanders WD, Pass RF, Cannon MJ. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988-1994. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1143–1151. PMID: 17029132.

2. Rafailidis PI, Mourtzoukou EG, Varbobitis IC, Falagas ME. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in apparently immunocompetent patients: a systematic review. Virol J. 2008; 5:47. DOI: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-47. PMID: 18371229.

3. Goodgame RW. Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 119:924–935. PMID: 8215005.

4. Jenkins RE, Peters BS, Pinching AJ. Thromboembolic disease in AIDS is associated with cytomegalovirus disease. AIDS. 1991; 5:1540–1542. PMID: 1667576.

5. Bauduer F, Blanc A, Cordon B. Deep vein thrombosis and acute cytomegalovirus infection: case report and review of the literature. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2003; 14:489–491. PMID: 12851536.

6. Abgueguen P, Delbos V, Chennebault JM, Payan C, Pichard E. Vascular thrombosis and acute cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients: report of 2 cases and literature review. Clin Infect Dis. 2003; 36:E134–E139. PMID: 12766855.

7. Fridlender ZG, Khamaisi M, Leitersdorf E. Association between cytomegalovirus infection and venous thromboembolism. Am J Med Sci. 2007; 334:111–114. PMID: 17700200.

8. Abgueguen P, Delbos V, Ducancelle A, Jomaa S, Fanello S, Pichard E. Venous thrombosis in immunocompetent patients with acute cytomegalovirus infection: a complication that may be underestimated. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010; 16:851–854. PMID: 19686279.

9. Rahbar A, Söderberg-Nauclér C. Human cytomegalovirus infection of endothelial cells triggers platelet adhesion and aggregation. J Virol. 2005; 79:2211–2220. PMID: 15681423.

10. Delbos V, Abgueguen P, Chennebault JM, Fanello S, Pichard E. Acute cytomegalovirus infection and venous thrombosis: role of antiphospholipid antibodies. J Infect. 2007; 54:e47–e50. PMID: 16701900.

11. Zhou YF, Yu ZX, Wanishsawad C, Shou M, Epstein SE. The immediate early gene products of human cytomegalovirus increase vascular smooth muscle cell migration, proliferation, and expression of PDGF beta-receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999; 256:608–613. PMID: 10080946.

12. Ladd AM, Goyal R, Rosainz L, Baiocco P, DiFabrizio L. Pulmonary embolism and portal vein thrombosis in an immunocompetent adolescent with acute cytomegalovirus hepatitis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009; 28:496–499. PMID: 19116696.

13. Galiatsatos P, Shrier I, Lamoureux E, Szilagyi A. Meta-analysis of outcome of cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent hosts. Dig Dis Sci. 2005; 50:609–616. PMID: 15844689.

Fig. 1

Endoscopic findings. Colonoscopy revealed a giant ulcer with an irregular margin and skip lesions in the distal colon.

Fig. 2

Chest X-ray findings. Chest radiograph revealed an engorged pulmonary trunk with an abrupt cutoff of pulmonary vascularity in the distal portions bilaterally, indicative of the "Westermark sign" (arrows).

Fig. 3

Chest CT finding. Chest CT scan showed filling defects within the pulmonary trunk and main pulmonary arteries (arrows).

Fig. 4

Histopathological findings. (A) Histological examination of biopsy specimens showed cytomegalic cells in the epithelium. The cells had large, densely stained nuclei and intranuclear inclusion bodies (arrows) on H&E (magnification, ×400). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis showed positive reaction for monoclonal anti-cytomegalovirus antibodies (arrows; magnification, ×400).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download