This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Background/Aims

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of colorectal neoplasia in subjects with fundic gland polyps (FGPs) and the relationship between FGPs and colorectal neoplasia in Korea.

Methods

We analyzed 128 consecutive patients with FPGs who underwent colonoscopy between January 2009 and December 2013. For each case, age- (±5 years) and sex-matched controls were identified from among patients with hyperplastic polyps, gastric neoplasms, and healthy controls. Clinical characteristics were reviewed from medical records, colonoscopic findings, pathologic findings, and computed tomography images. The outcome was evaluated by comparison of advanced colonic neoplasia detection rates.

Results

Of the 128 patients, seven (5.1%) had colon cancers and seven (5.1%) had advanced adenomas. A case-control study revealed that the odds of detecting a colorectal cancer was 3.8 times greater in patients with FGPs than in the age- and sex-matched healthy controls (odds ratio [OR], 3.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–13.24; P =0.04) and 4.1 times greater in patients with FGPs than in healthy controls over 50 years of age (OR, 4.10; 95% CI, 1.16–14.45; P =0.04). Among patients with FGPs over 50 years old, male sex (OR, 4.83; 95% CI, 1.23–18.94; P =0.02), and age (OR, 9.90; 95% CI, 1.21–81.08; P =0.03) were associated with an increased prevalence of advanced colorectal neoplasms.

Conclusions

The yield of colonoscopy in colorectal cancer patients with FGPs was substantially higher than that in average-risk subjects. Colonoscopy verification is warranted in patients with FGPs, especially in those 50 years of age or older.

Keywords: Fundic gland polyp, Colorectal neoplasia, Colonoscopy, Risk factors, Case-control studies

INTRODUCTION

The use of endoscopy for cancer screening has rapidly increased in recent years; consequently, incidental findings of fundic gland polyps (FGPs) during routine endoscopy have also rapidly increased, ranging from 0.5% to 11.1%.

12345 Histologically, FGPs are characterized by cystically dilated and irregularly budded fundic glands, lined by flattened parietal cells, chief cells, and variable numbers of mucous neck cells.

67 FGPs are usually located in the body and fundus of the stomach and rarely cause upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. FGPs are considered benign lesions, but they often cause unnecessary anxiety.

8 To date, the etiology of FGPs remains unclear. Some studies have reported that the incidence of FGPs has dramatically increased due to the use of proton pump inhibitors and the decreased prevalence of

Helicobacter pylori infection in Western countries.

46

Epidemiologic evidence regarding an association between FGPs and colorectal neoplasia has been reported, indicating that a substantial proportion of patients with FGPs is affected by colorectal neoplasia.

9 In addition, a recent study reported an association between FGPs and colorectal malignancy.

1011 Interestingly, a molecular analysis showed that FGPs develop sporadically with a mutation of the β-catenin gene, a key factor in the development of colorectal cancer.

1 In contrast, a population based-study reported that there was no association between FGPs and colorectal neoplasm.

1213 More importantly, little research has been conducted among Asians. Therefore, there are controversies regarding the necessity of subjecting patients with FGPs to colonoscopy.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the yield of colonoscopy for detecting colorectal neoplasia in subjects with and without FGPs and to define the relationship between FGPs and colorectal neoplasia in Korea.

METHODS

1. Patients and Data Collection

Our study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital. We enrolled consecutive patients with FGPs for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) followed by colonoscopy within two years between January 2009 and December 2013.

Patients were included using the following criteria: (1) age over 20 years old and (2) performance of gastroscopy due to a routine check-up or upper GI symptoms such as dyspepsia, epigastric pain, or heartburn. Exclusion criteria for the study included (1) other co-existing pathologic types of polyps in the stomach; (2) a history of GI bleeding such as melena, hematemesis, or hematochezia; (3) a previous history of gastric surgery for any reason; (4) gastric submucosal tumors, carcinoid tumor, malignant lymphoma, or MALToma; and (5) any kind of polyposis syndrome, including Familial adenomatosis polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Furthermore, we excluded patients who underwent colonoscopy due to GI bleeding. Patients with a history of colorectal cancer, IBD, and colorectal surgery were also excluded. In addition, patients who underwent a colonoscopy one year before the diagnosis of FGP were excluded. Clinical and pathologic data, including indication for colonoscopy, were obtained using the electronic medical recording system at our center. Data collected included age, sex, and the number and size of polyps.

2. Endoscopy

EGD (GF-H260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and colonoscopy (CF-H260; Olympus) was performed at the Endoscopy Center at Seoul National University Boramae Hospital. All colonoscopies were conducted by a board-certified gastroenterologist. All abnormal findings including polyps detected during endoscopy were subjected to biopsy sampling. In addition, endoscopic mucosal resection was performed using hypertonic saline and snare if the polyp size was greater than 5 mm by visual comparison using biopsy forceps.

Advanced adenoma was defined as an adenoma of over 10 mm in size or the presence of a >25% villous component or high-grade dysplasia on pathologic examination. Non-advanced neoplasm was defined as an adenoma below 10 mm in size with low-grade dysplasia and/or the presence of a <25% villous component. Colorectal cancer was defined as intramucosal carcinomas or invasive carcinomas. The presence of advanced neoplasm was defined as the detection of either advanced adenoma or colorectal cancer. Metastatic colorectal cancer was not considered colorectal cancer. In patients with multiple lesions, the most advanced lesions were included in our analysis.

The diagnosis of FGP was confirmed when histological examination of the polyps revealed fundic mucosa with one or more cystically dilated glands, lined by flattened parietal cells, chief cells, and variable numbers of mucous neck cells.

67

3. Case-Control Study

A case control study was undertaken to investigate whether patients with FGP had an increased risk of advanced colonic neoplasia. For each FGP case, two or more age- (±5 years) and sex-matched controls were identified from among subjects without FGPs and patients with hyperplastic polyps (HP) and gastric neoplasm including adenoma and malignancy diagnosed by EGD followed by a colonoscopy within two years. We excluded patients who underwent colonoscopy due to GI bleeding. In addition, patients with a history of colorectal cancer, IBD, and colorectal surgery were excluded. Patients who underwent a colonoscopy one year before the EGD were also excluded. The outcome was evaluated by comparison of rates of detection of advanced colonic neoplasia.

4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 18.0, IBM, NY, USA) for Windows. Means and SD were calculated for continuous variables and comparisons between groups were made using Student's t-test. The significance of possible associations between discrete variables was compared by Pearson chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Multiple correlations were calculated by logistic regression. In this test, a P-value <0.20 was required for entry into a binary logistic regression analysis model used to identify the risk factors. Statistical significance was determined using a P-value <0.05.

RESULTS

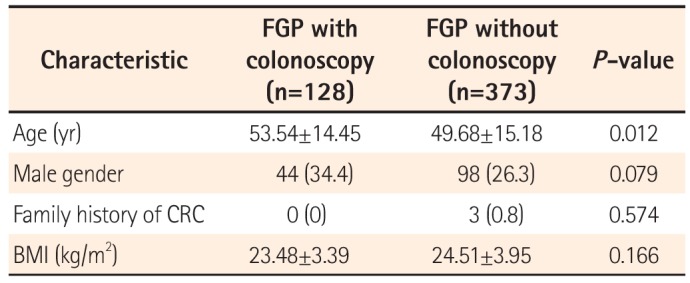

1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With FGP

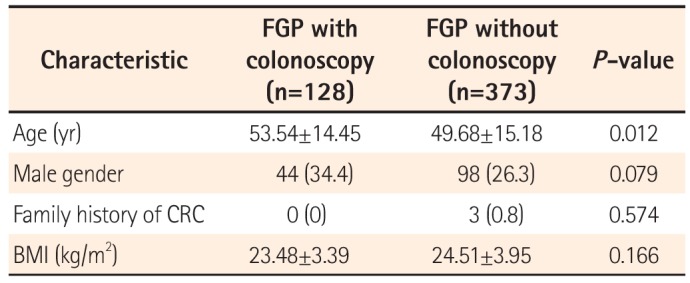

A total of 500 patients with a histologically confirmed FGP were identified. Of these subjects, colonoscopy had been performed within two years from the date of EGD in 128 patients (25.6%). The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age of the 128 patients was 53.54 (SD=14.45) years; none of the patients had a family history of colorectal cancer. The mean BMI was 23.48 kg/m

2. Of the 373 FGP patients who did not undergo colonoscopy, the mean age was 49 years (SD=15.18), and three of the patients had a family history of colorectal cancer; the mean BMI was 24.51 kg/m

2.

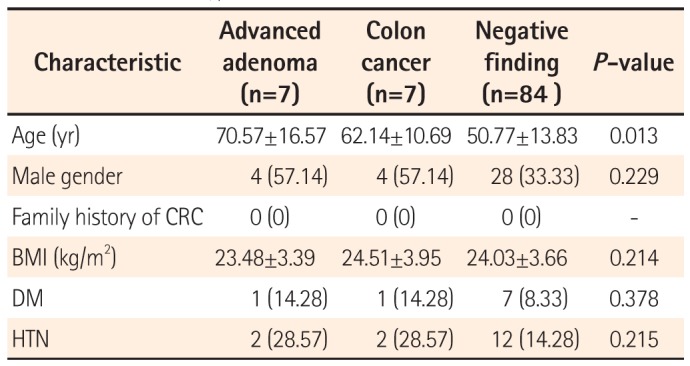

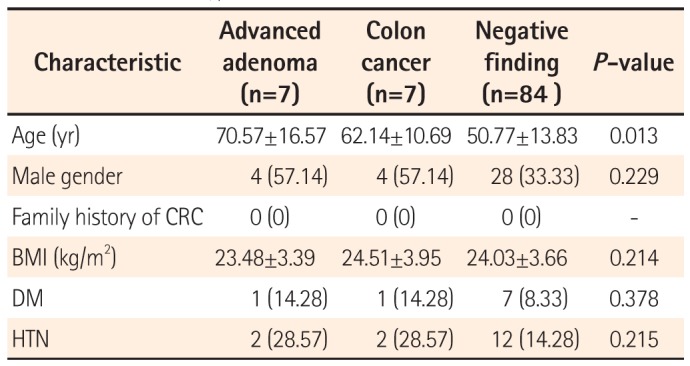

2. Clinical Characteristics of Advanced Colonic Neoplasia in Patients With FGP

The clinical characteristics of the patients enrolled are summarized in

Table 2. The mean age of the seven patients with advanced adenoma and seven patients with colon cancer was 70.57 (SD=16.57) years and 62.14 (SD=10.69) years, respectively. The mean age of the 84 patients with negative findings on colonoscopy was 50.77 (SD=13.83) years. BMI did not differ significantly between the three groups. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) was 14.28% in the advanced adenoma group, 14.28% in the colon cancer group, and 8.33% in the group with normal findings with FGPs. The prevalence of hypertension (HTN) was 28.57% in the advanced adenoma group, 28.57% in the colon cancer group, and 14.28% in the group with normal findings with FGPs. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of DM or HTN among the three groups.

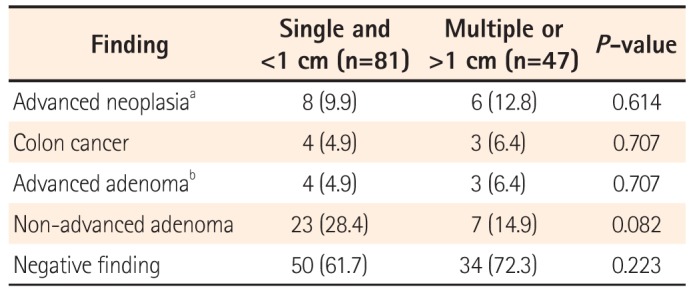

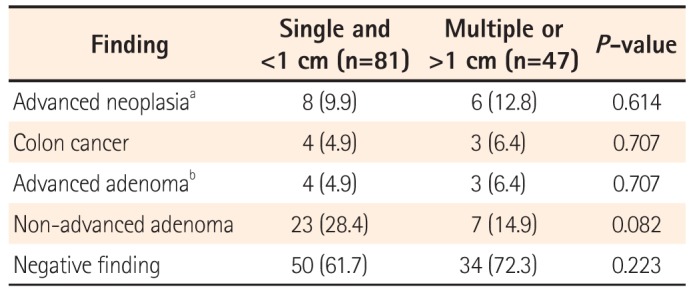

3. Colonoscopy Findings in Patients With FGP

Table 3 shows the results of colonoscopy in patients with FGPs. Overall, 14 patients had advanced colonic neoplasia, including seven with colon cancers. Among these patients, 81 (63.3%) had a single FGP smaller than 1 cm, and of these, eight exhibited advanced neoplasia, including four with colon cancers. Forty-seven (36.7%) patients had two or more FGPs, or at least one FGP >1 cm, and of these, 6 (12.8%) were diagnosed with advanced neoplasia, including 3 (6.4%) with colon cancers. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of advanced neoplasia between the two groups.

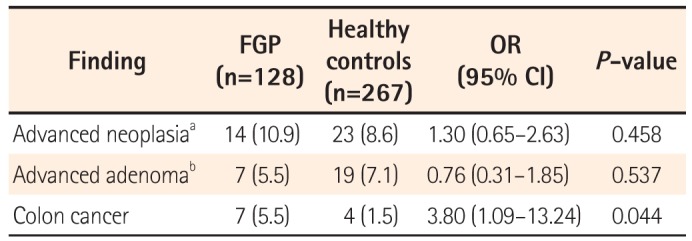

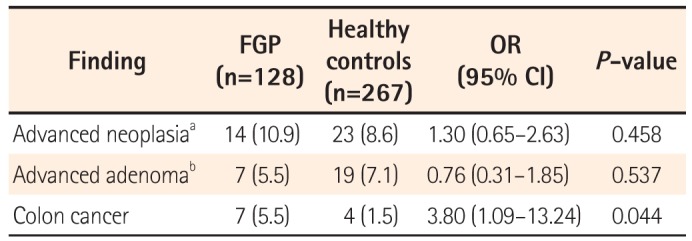

4. Case-Control Analysis of Risk Factors for Advanced Colonic Neoplasia in Patients With FGP

The odds of detecting advanced colonic neoplasia in patients with FGP were analyzed by comparison with 276 subjects without FGPs. The two groups were not different with regards to the indication for colonoscopy (

P =0.172). Overall, the odds of advanced colonic neoplasia occurring in FGP patients were 1.3 times higher than that in the subjects without FGPs. This was not statistically significant. However, the odds of detecting colorectal cancer were approximately 3.8 times higher than that in controls (OR, 3.804; 95% CI, 1.093–13.239;

P =0.044) (

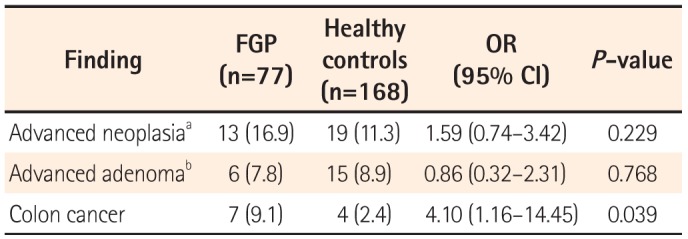

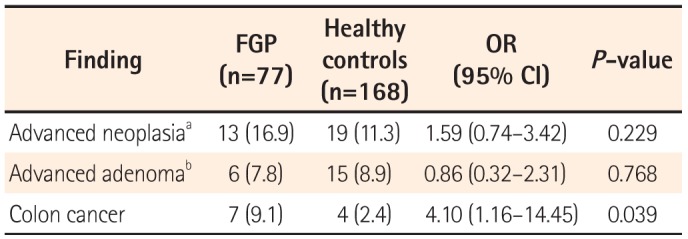

Table 4). In addition, in the comparison between the FGP group and the subjects without FGPs for those aged 50 or older, the odds for detecting colon cancer in patients with FGPs increased up to 4.1 times compared to that in the controls (

Table 5).

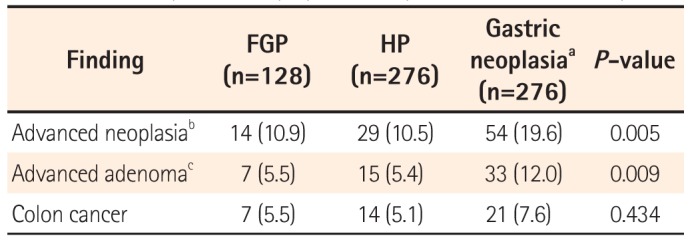

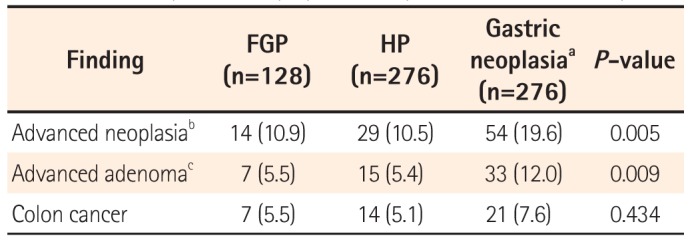

5. Comparison Among Groups With HP and Gastric Neoplasm

The prevalence of advanced neoplasm in the gastric FGP group, the HP group, and the gastric neoplasia group are summarized in

Table 6. The prevalence of advanced neoplasm was 10.9% in the FGP group, 10.5% in the HP group, and 19.6% in the neoplasm group. This difference among the three groups was significant. In the subgroup analysis, patients with gastric neoplasm had an increased risk of advanced colonic neoplasia than those with FGPs or HP. However, there was no difference in the prevalence of colorectal cancer among the three groups. In the subgroup analysis, there was no difference in the prevalence of colorectal cancer between the FGP group and the gastric neoplasia group.

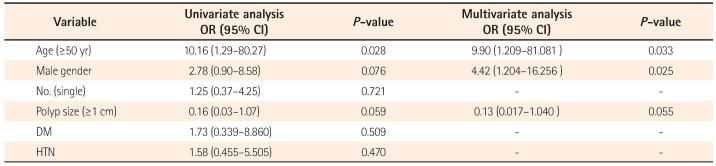

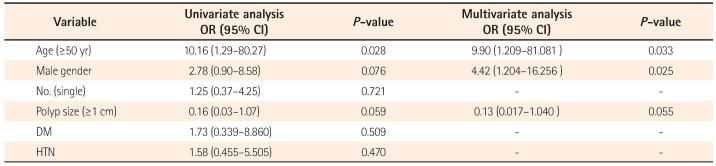

6. Risk Factors for Advanced Colonic Neoplasia in Patients With FGP

In the univariate analyses, older age (over 50 years) was associated with an increased risk of advanced neoplasm (OR, 10.156; 95% CI, 1.285–80.271;

P =0.028). In addition, in a multivariate analysis with logistic regression analysis that included age, male sex, the number and size of FGPs, DM, and HTN as predictors, the risk factors for advanced neoplasm were age and male sex, with ORs of 9.9 (95% CI, 1.209–81.081;

P =0.033) and 4.4 (95% CI, 1.204–16.256;

P =0.025), respectively (

Table 7).

DISCUSSION

Our study, which included FGP patients who had undergone colonoscopy within 2 years after diagnosis by histopathology, evaluated the need for colonoscopy verification in patients with FGPs. In our cohort, 14 patients (10.9%) with FGP had advanced colonic neoplasia, including seven patients (5.5%) with colorectal cancer. This finding suggested that a substantial proportion of patients with FGPs had advanced colonic neoplasia including colorectal malignancy.

Recent studies have produced controversial results regarding the association between FGPs and colorectal neoplasia.

101113 In addition, there have been few studies performed in the Asian population. In one study performed in Korea, there was no significant difference in the detection of colorectal neoplasia between FGP patients and controls. However, this study did not analyze the risk of advanced colonic neoplasia and colorectal malignancy in patients with FGPs.

1415 Therefore, the present study was performed to evaluate the yield of colonoscopy for the detection of colorectal neoplasia in subjects with or without FGPs, and to determine whether colonoscopy is warranted in patients with FGPs. In our study, the yields of colonoscopy in advanced colonic neoplasia in patients with FGPs and controls were 10.9% and 8.6%, respectively, which were not significantly different. However, seven patients with FGPs had colorectal malignancy. The odds of detecting colorectal malignancy in patients with FGPs were approximately 3.8 times greater than that in the age- and sex-matched controls. More importantly, the risk of advanced colonic neoplasia including colorectal cancer was even greater in patients aged 50 years or older compared with control subjects. This finding suggests that colonoscopy verification is strongly warranted for Asian patients with FGPs, especially for those 50 years of age or older. However, among the 55 patients aged below 50 years, only one patient had advanced neoplasia without malignancy, suggesting that colonoscopy verification may not be necessary for all patients with FGPs.

16

Several studies have shown an association between colorectal and gastric adenoma or cancer. A meta-analysis of 24 case-control studies in China suggested that the prevalence of colorectal polyps was higher in patients with gastric polyps than in those without gastric polyps and that the risk of colorectal neoplasms may increase significantly in patients with gastric polyps, neoplasms, and duodenal neoplasia.

17 Another study performed in Korea reported that the risk of colorectal adenoma or cancer increased significantly in patients with gastric adenoma or cancer and that intestinal type gastric cancer was an independent risk factor for colorectal adenoma or cancer in patients younger than 50 years.

18 In the present study, the diagnostic yield of colonoscopy for colorectal cancer was similar in patients with gastric neoplasia and in those with FGPs. Therefore, the gastroenterologist should be aware of the risk of colonic neoplasia in patients with FGPs and recommend colonoscopy verification when patients present with potential risk factors such as old age.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature and the fact it was conducted at a single institution, which may reflect a selection bias since we were unable to include the entire population of FGP patients. However, we strived to minimize the limitations by including age- and sex-matched controls. In addition, we only included FGP patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis. Moreover, all cases and controls underwent total colonoscopy and all the colon lesions were confirmed histopathologically. More importantly, we included age- and sex-matched patients with gastric neoplasia to compare the yield of colonoscopy for advanced colonic neoplasia. Through the study design, we believe that our data provides valuable information regarding the risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with FGPs.

In conclusion, the yield of colonoscopy for the detection of colorectal cancer in patients with FGPs was substantially higher than that in average-risk subjects. Colonoscopy verification is warranted in patients with FGPs, especially in those 50 years of age or older. However, colonoscopy verification can be eliminated in patients with FGPs who are younger than 50 years of age.

Table 1

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Fundic Gland Polyps (FGP) According to the Colonoscopy Examination

|

Characteristic |

FGP with colonoscopy

(n=128) |

FGP without colonoscopy

(n=373) |

P-value |

|

Age (yr) |

53.54±14.45 |

49.68±15.18 |

0.012 |

|

Male gender |

44 (34.4) |

98 (26.3) |

0.079 |

|

Family history of CRC |

0 (0) |

3 (0.8) |

0.574 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

23.48±3.39 |

24.51±3.95 |

0.166 |

Table 2

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Advanced Colon Neoplasia With Fundic Gland Polyps

|

Characteristic |

Advanced adenoma

(n=7) |

Colon cancer

(n=7) |

Negative finding

(n=84 ) |

P-value |

|

Age (yr) |

70.57±16.57 |

62.14±10.69 |

50.77±13.83 |

0.013 |

|

Male gender |

4 (57.14) |

4 (57.14) |

28 (33.33) |

0.229 |

|

Family history of CRC |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

- |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

23.48±3.39 |

24.51±3.95 |

24.03±3.66 |

0.214 |

|

DM |

1 (14.28) |

1 (14.28) |

7 (8.33) |

0.378 |

|

HTN |

2 (28.57) |

2 (28.57) |

12 (14.28) |

0.215 |

Table 3

Colonoscopy Results in Patients With Fundic Gland Polyps According to the Size and Number Identified

|

Finding |

Single and <1 cm (n=81) |

Multiple or >1 cm (n=47) |

P-value |

|

Advanced neoplasiaa

|

8 (9.9) |

6 (12.8) |

0.614 |

|

Colon cancer |

4 (4.9) |

3 (6.4) |

0.707 |

|

Advanced adenomab

|

4 (4.9) |

3 (6.4) |

0.707 |

|

Non-advanced adenoma |

23 (28.4) |

7 (14.9) |

0.082 |

|

Negative finding |

50 (61.7) |

34 (72.3) |

0.223 |

Table 4

Diagnostic Yield of Advanced Neoplasia Between Patients With Fundic Gland Polyps (FGP) and Healthy Controls of All Ages

|

Finding |

FGP

(n=128) |

Healthy controls

(n=267) |

OR

(95% CI) |

P-value |

|

Advanced neoplasiaa

|

14 (10.9) |

23 (8.6) |

1.30 (0.65–2.63) |

0.458 |

|

Advanced adenomab

|

7 (5.5) |

19 (7.1) |

0.76 (0.31–1.85) |

0.537 |

|

Colon cancer |

7 (5.5) |

4 (1.5) |

3.80 (1.09–13.24) |

0.044 |

Table 5

Diagnostic Yield of Advanced Neoplasia Between Patients With Fundic Gland Polyps (FGP) and Healthy Controls More Than 50 Years of Age

|

Finding |

FGP

(n=77) |

Healthy controls

(n=168) |

OR

(95% CI) |

P-value |

|

Advanced neoplasiaa

|

13 (16.9) |

19 (11.3) |

1.59 (0.74–3.42) |

0.229 |

|

Advanced adenomab

|

6 (7.8) |

15 (8.9) |

0.86 (0.32–2.31) |

0.768 |

|

Colon cancer |

7 (9.1) |

4 (2.4) |

4.10 (1.16–14.45) |

0.039 |

Table 6

Diagnostic Yield of Advanced Neoplasia Among Patients With Fundic Gland Polyps (FGP), Hyperplastic Polyps (HP), and Gastric Neoplasia

|

Finding |

FGP

(n=128) |

HP

(n=276) |

Gastric neoplasiaa

(n=276) |

P-value |

|

Advanced neoplasiab

|

14 (10.9) |

29 (10.5) |

54 (19.6) |

0.005 |

|

Advanced adenomac

|

7 (5.5) |

15 (5.4) |

33 (12.0) |

0.009 |

|

Colon cancer |

7 (5.5) |

14 (5.1) |

21 (7.6) |

0.434 |

Table 7

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis for Advanced Neoplasm in Patients With Fundic Gland Polyps

|

Variable |

Univariate analysis

OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

Multivariate analysis

OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

|

Age (≥50 yr) |

10.16 (1.29–80.27) |

0.028 |

9.90 (1.209–81.081) |

0.033 |

|

Male gender |

2.78 (0.90–8.58) |

0.076 |

4.42 (1.204–16.256) |

0.025 |

|

No. (single) |

1.25 (0.37–4.25) |

0.721 |

- |

- |

|

Polyp size (≥1 cm) |

0.16 (0.03–1.07) |

0.059 |

0.13 (0.017–1.040 ) |

0.055 |

|

DM |

1.73 (0.339–8.860) |

0.509 |

- |

- |

|

HTN |

1.58 (0.455–5.505) |

0.470 |

- |

- |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download