Abstract

Background/Aims

This study aimed to document the recent etiological spectrum of chronic diarrhea with malabsorption and also to compare features that differentiate tropical sprue from parasitic infections, the two most common etiologies of malabsorption in the tropics.

Methods

We analyzed 203 consecutive patients with malabsorption. The etiological spectrum and factors that differentiated tropical sprue from parasitic infections were analyzed.

Results

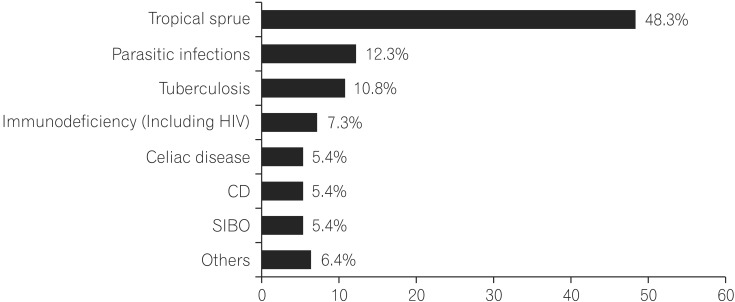

The most common etiology was tropical sprue (n=98, 48.3%) followed by parasitic infections (n=25, 12.3%) and tuberculosis (n=22, 10.8%). Other causes were immunodeficiency (n=15, 7.3%; 12 with human immunodeficiency virus and 3 with hypogammaglobulinemia), celiac disease (n=11, 5.4%), Crohn's disease (n=11, 5.4%), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (n=11, 5.4%), hyperthyroidism (n=4, 1.9%), diabetic diarrhea (n=4, 1.9%), systemic lupus erythematosus (n=3, 1.4%), metastatic carcinoid (n=1, 0.5%) and Burkitt's lymphoma (n=1, 0.5%). On multivariate analysis, features that best differentiated tropical sprue from parasitic infections were larger stool volume (P=0.009), severe weight loss (P=0.02), knuckle hyperpigmentation (P=0.008), low serum B12 levels (P=0.05), high mean corpuscular volume (P=0.003), reduced height or scalloping of the duodenal folds on endoscopy (P=0.003) and villous atrophy on histology (P=0.04). Presence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms like bloating, nausea and vomiting predicted parasitic infections (P=0.01).

Chronic small bowel diarrhea with malabsorption continues to be a major public health problem worldwide. The world is sharply divided by two sprue diseases, with celiac sprue most common in the west and tropical sprue most common in the developing world, including India.123 However, this divide in recent years seems to be less precise with increasing reports of celiac disease emerging in India.4 There have been major government and public campaigns going on in India to improve sanitation, hygienic conditions and quality of food and water. With that, a decline is expected in the incidence of tropical sprue and infection-related chronic diarrhea. One recent study from north India4 and an older study from western India5 documented that celiac disease is getting the top rank among patients with chronic diarrhea with malabsorption. However, the rest showed that tropical sprue remains the leader.36 So, our study aimed to determine whether the trend in etiology is really changing in India.

Tropical sprue and parasitic diseases (giardiasis, strongyloidiasis, cryptosporidiosis, microsporidiosis, isosporidiosis) are two leading causes of chronic diarrhea with malabsorption in tropical countries. Tropical sprue is a diagnosis of exclusion. In parasitic diseases, many a times, the organism is not picked up in stool examination or in small bowel biopsy specimen. So, it is important to differentiate these two diseases on the basis of symptoms, laboratory parameters and endoscopic findings. This will help us in instituting specific empirical treatment on the basis of the above said features. So, our study also aimed to identify various features that differentiate two widely prevalent etiologies of chronic small bowel diarrhea with malabsorption.

The study was conducted from August 2011 to May 2015. We included patients attending our gastroenterology outpatient department which also included referral patients from other departments and peripheral centers. We also included inpatients of the gastroenterology and general medicine wards. A consecutive 212 patients who were >12 years of age who fulfilled the following criteria were enrolled in our study. The study was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of our institute. Informed consent was provided by each patient. Patients with chronic diarrhea (>4 weeks duration) with any two of the following three features were included the study. (1) Presence of more than 10 fat droplets/high power field in stool examination, (2) significant weight loss (>5% in less than 6 months) and (3) presence of anemia (hemoglobin [Hb] <11 g/dL) and/or hypoalbuminemia (serum level <3.5 g/dL) and/or features of other micronutrient deficiencies. Patients with lactose intolerance (based on clinical suspicion) and those with chronic pancreatitis and exocrine insufficiency were excluded from the study. Of the total 212 patients included, 6 had chronic pancreatitis and 3 had lactose intolerance and were excluded. Thus, 203 patients were included in the final analysis.

All enrolled patients were asked about their stool frequency, consistency, volume, presence of blood/mucus, borborygmi, abdominal pain, upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and degree of weight loss. All patients underwent basic blood investigations including complete hemogram with blood indices and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver and renal function tests, fasting blood sugar, serum electrolytes (Na, K, Ca, Mg), thyroid function tests, iron profile and serum B12 levels.

A spot stool sample was sent for routine microscopic examination including stool fat detection (Sudan III stain). More than 10 droplets per high power field were considered as positive stool fat test. Three consecutive samples were sent to detect opportunistic parasites. The stool was examined by wet and iodine mount to look for giardial cysts. Special stains like modified Kinyoun's acid fast stain and Ryan blue stain were used to detect cryptosporidium, cyclospora, isospora or microspora.

We performed esophagogastroduodenoscopy and collected four biopsy samples from the second part of the duodenum (D2) and one from the duodenal bulb from all patients. In patients suspected to have small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) who had not received prior antibiotics, a jejunal aspirate was obtained after a povidone iodine mouthwash and gargle, using sterile catheters after sterilization of the endoscope channel with 2% glutaraldehyde and sent for culture. Colonoscopy with ileal intubation was performed in selected patients. Biopsies were evaluated by an experienced pathologist. Histological grading of D2 biopsies were given according to modified Marsh criteria.7

Serum IgA tissue transglutaminase (tTG) (by Enzyme immunoassay method) was measured in patients suspected to have celiac disease on clinical grounds. Serum levels of Ig were done in selected patients. Patients with strongly suspected celiac disease with negative IgA tTG and low level of IgA underwent Serum IgG tTG. All patients were tested for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) -1 and HIV-2 antibodies by ELISA.

The diagnosis of giardiasis was made on the basis of finding trophozoites in the D2 biopsy or cyst/trophozoites in the spot stool examination. Strongyloidosis was diagnosed by the presence of larvae in stool or D2 biopsy. Isospora, cryptospora and microspora were diagnosed by the presence of their respective cysts in any of the three consecutive stool sample stained with special stains like modified Kinyoun's acid fast stain and Ryan blue stain. We diagnosed TB by suggestive endoscopic features AND the presence of AFB in the biopsy or histopathological features (especially caseating granulomas) or detection of AFB by TB PCR or TB mycobacteria growth indicator tube culture.8 CD was diagnosed according to European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) criteria, i.e., combination of endoscopic features, histopathology, radiological imaging and response to treatment. 9 Celiac disease was detected by presence of IgA tTG, suggestive histology and response to gluten free diet. SIBO was diagnosed by growth of >105 bacterial colonies/mL in culture and response to antibiotics. Hypogammaglobulinemia was diagnosed on the basis of low serum level of one or more Ig (IgG, IgA or IgM). We diagnosed tropical sprue when all the above said work up was negative and response to doxycycline 100 mg/day and folic acid 5 mg/day was seen.10

Patients with tropical sprue were treated with doxycyline and folic acid for 6 months. Patients with TB were given treatment with anti-tubercular drugs with serial monitoring of liver function tests. Patients with CD were treated with mesalazine or steroids and immunosuppressants. Patients with celiac disease were put on a gluten-free diet with the help of the hospital nutritionist. Patients with HIV and a CD4 count less than 350 were started on antiretroviral drugs. Patients with SIBO were treated with antibiotics. All parasitic infections were treated with metronidazole or nitazoxanide, according to etiology. Strongyloidosis hyperinfection was treated with albendazole and ivermectin. All patients were followed up every month in our outpatient department and treatment response in the form of weight gain, improved stool frequency, anemia and pedal edema were noted.

We analyzed the data using SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data of each variable were analyzed for normal distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test. All parametric and non-parametric unpaired continuous data were analyzed using Student's t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. All categorical data was analyzed using the chi-square test. Parameters found significant on univariate analysis were analyzed using a step-wise logistic regression method. P-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to determine the best cut-off values of parameters that best differentiated tropical sprue from parasitic malabsorption.

The mean age (±SD) of the study population was 36.5±12.6 years, and 49% of the patients were male. Median stool frequency was six times per day (Interquartile range [IQR], 5–8). Median duration of symptoms was 6 months (IQR, 4–7). Patients had a mean weight loss of 9.4±4.1 kg.

Most common cause of chronic diarrhea with malabsorption was tropical sprue (n=98, 48.3%) followed by parasitic infection (n=25, 12.3%)(Fig. 1). Among parasitic infections, giardiasis was most common (n=12, 5.9%) followed by cryptosporidium (n=6, 3%), microsporidia (n=5, 2.5%) and strongyloidosis (n=2, 1%). Other common causes were TB (n=22, 10.8%; 21 ileocecal and 1 duodenal), immunodeficiency (n=15, 7.3%; 12 HIV and 3 hypogammaglubulinemia), celiac disease (n=11, 5.4%), CD (11, 5.4%) and SIBO (n=11, 5.4%). Other less common causes found were hyperthyroidism (n=4, 1.9%), diabetic diarrhea (n=4, 1.9%), systemic lupus erythematosus (n=3, 1.4%), metastatic carcinoid (n=1, 0.5%) and ileal Burkitt's lymphoma (n=1, 0.5%).

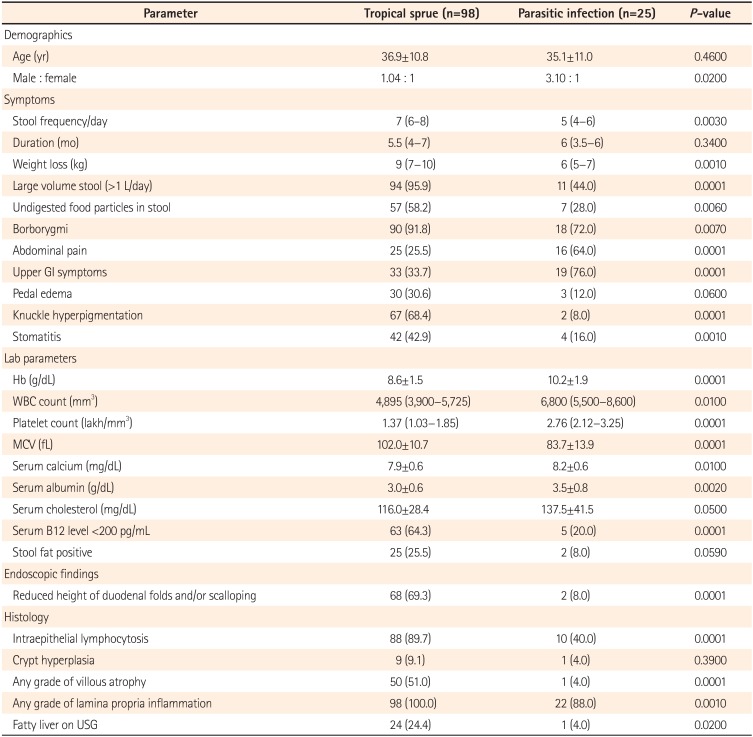

The demographic, clinical and laboratory parameters of tropical sprue and parasitic infections are shown in Table 1.

Patients with tropical sprue and parasitic infections had a similar age of presentation (mean, 36.9 vs. 35.1 years; P=0.46). Tropical sprue affects men and women equally but parasitic infections occur more commonly in men (M:F ratio 1:1 vs. 3:1, P=0.02). Patients with tropical sprue have more severe symptoms than those with parasitic infections such as higher stool frequency per day (P=0.003), more voluminous stool (P=0.0001), more borborygmi (P=0.007) and undigested food particles in stool (P=0.006). Duration of disease at presentation was similar in both diseases (P=0.34). Degree of weight loss was more severe in patients with tropical sprue (P=0.001). Features suggestive of nutrient deficiencies like knuckle hyperpigmentation (P=0.0001) and stomatitis (P=0.001) were more common in patients with tropical sprue. A very striking feature about parasitic infections is a more common occurrence of upper GI symptoms such as bloating, nausea and vomiting as compared to tropical sprue (79% vs. 33.7%; P=0.0001).

Mean Hb (g/dL) (8.6 vs. 10.2, P=0.0001) and platelet count (lakh/mm3) (1.37 vs. 2.76, P=0.0001) were lower in patients with tropical sprue. Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) was higher in patients with tropical sprue (102 vs. 83.7, P=0.0001). Serum albumin, calcium, B12 and cholesterol levels were significantly lower in patients with tropical sprue as compared to those with parasitic infections. Median B12 level was 149 pg/mL (IQR, 97–332) and 412 pg/mL (IQR, 233–788) in patients with tropical sprue and parasitic infections, respectively (P=0.001).

On endoscopy, duodenal scalloping or reduced height of duodenal folds were found in 68% and 8% of the patients with tropical sprue and parasitic infections, respectively (P=0.0001). On histology, intraepithelial lymphocytosis was more common in tropical sprue (P=0.0001) but crypt hyperplasia was seen in similar proportion of patients (P=0.39). Just one patient (4%) with parasitic infection had villous atrophy, as opposed to 51% of those with tropical sprue.

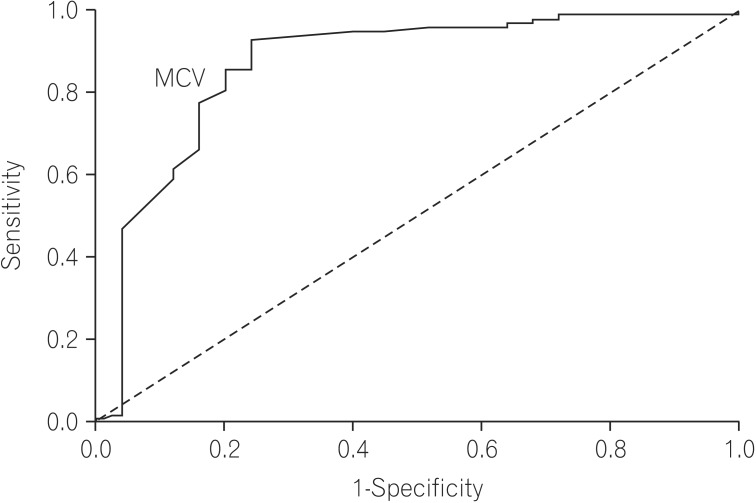

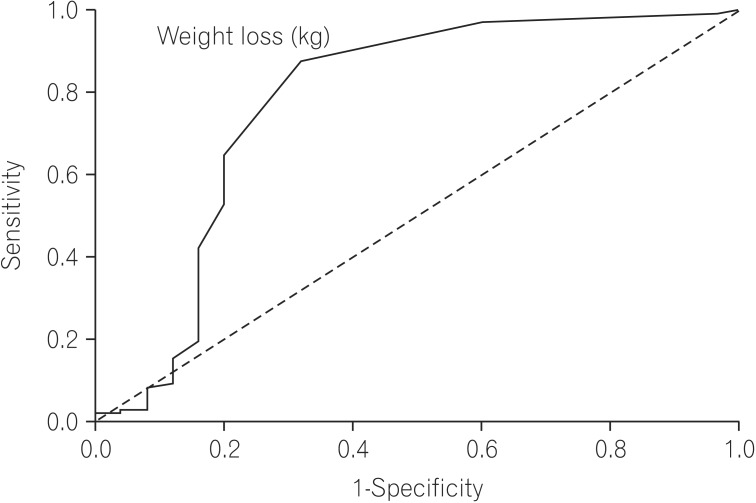

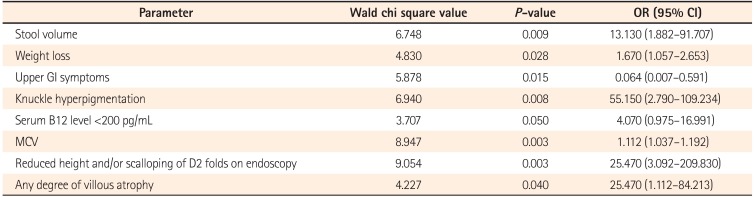

Multivariate analysis by logistic regression (Table 2) was performed for variables that were significant on univariate analysis. Larger stool volume (P=0.009), more severe weight loss (P=0.02), knuckle hyperpigmentation (P=0.008), high MCV (P=0.003), reduced height of duodenal folds and/or scalloping and any degree of villous atrophy (P=0.04) were associated with tropical sprue. The best cut off value of MCV that differentiated tropical sprue from parasitic infections was 91 fL (area under the ROC curve [AUROC], 0.869; sensitivity, 85.7%; specificity, 80%) (Fig. 2). The best cut off value of degree of weight loss for the same was 7.5 kg (AUROC, 0.774; sensitivity, 64.3%; specificity, 80%) (Fig. 3).

Among parasitic infections, giardiasis was the most common (n=12, 5.9%). Three, five and four patients were diagnosed by D2 biopsy, stool microscopy and both methods, respectively. One patient with giardiasis had low serum IgA and IgM levels. Among the patients wiith cryptosporidiosis (n=6, 3%), one had underlying HIV disease with CD4 count of 101/mm3. Among five patients with microsporidiosis, one had low serum level of Ig (IgA, IgG and IgM) and one had underlying HIV with CD4 count of 78/cu mm. Two patients presented with strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome. One among them presented with chronic diarrhea and duodenal stricture with underlying human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) infection and the other patient had a history of chronic steroid intake, as a risk factor.

Chronic small bowel diarrhea with malabsorption poses significant impairment to health related quality of life in India. India is apparently witnessing a paradigm shift from the infectious causes to non-infectious causes of malabsorption as the sanitation and hygienic conditions are improving. This fact was reported recently by Yadav et al. who concluded that the celiac disease was the most common cause of chronic diarrhea with malabsorption in northern India.4 But the rest of the country seems to still be grappling with tropical sprue. Studies from Ghoshal et al., from Dutta et al. from south India reported that celiac disease is a rapidly emerging disease but tropical sprue is still the leader.36 Our study shows that tropical sprue (48.3%) massively dominates the spectrum of chronic diarrhea with malabsorption. Moreover, infections like parasitic diseases (12.3%) and TB (10.8%) still hold the ground in India. Celiac disease is relatively rare (5.4%). These findings are in contrast to the earlier study reported from our center in 2006 that showed celiac disease (26%) as the most common etiology of malabsorption and tropical sprue (2%) was reported as very rare.5 This discrepancy may be explained by small sample size (n=50) and inadvertent inclusion of more patients with north Indian origin. In the study reported by Dutta et al. from south India, only 2 out of 19 patients with celiac disease were of south Indian origin.6 These findings do indicate that celiac disease is still a way behind other etiologies of malabsorption at least in population belonging to western and southern parts of the country.

Our study also revealed that the severity of symptoms and the degree of malabsorption were greater in patients with tropical sprue than parasitic infections. From multivariate analysis and ROC curves, we found that larger stool volume, weight loss >7.5 kg, more severe B12 deficiency (evident by low serum B12 level, MCV >91 fL and knuckle hyperpigmentation), reduced height of duodenal folds/scalloping and presence of villous atrophy are predictors of tropical sprue. The presence of upper GI symptoms such as nausea, vomiting or bloating are predictors of parasitic infection. This clinical distinction is particularly helpful for a subpopulation of patients labeled as having tropical sprue on the basis of a negative workup as mentioned in the methodology and not responding to doxycycline and folic acid. They may be harboring a chronic parasitic infection that was missed in stool or duodenal biopsy specimen, as is commonly observed in clinical practice. This select group of patients may be benefitted by empiric anti-parasitic treatment.

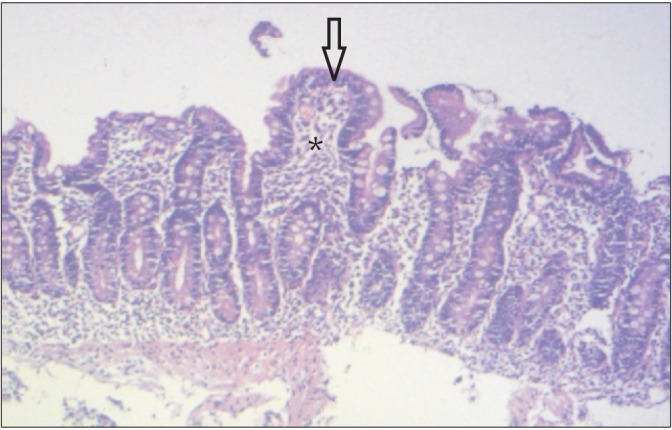

Klipstein and Baker defined tropical sprue as intestinal mucosal disease with malabsorption of at least two unrelated nutrients when all other known causes have been excluded.11 There were reports of epidemics of the disease in south India during 1960s with very high mortality.12 It is still the leading cause of malabsorption in India except in northern part. It is also seen in Southeast Asia, West Africa, Central America, South America, the Caribbean, and Puerto Rico. It primarily affects residents and travellers in tropical regions. In tropical sprue, an as-yet unidentified infective or toxic agent leads to damage to intestinal crypt stem cell thereby causing reduced absorptive cell lineage and resultant villous atrophy.13 Also contributory to the pathogenesis is the ileal brake mechanism resulting in SIBO.14 Common symptoms are chronic watery diarrhea, glossitis, borborygmi and weight loss with evidence of B12, protein, fat, carbohydrate and other nutrient deficiencies.15 The D2 biopsy reveals blunting of villi, crypt hyperplasia and infiltration of the lamina propria and epithelium by inflammatory cells (Fig. 4).16 The treatment of choice is doxycycline 100 mg/day and folic acid 5 mg/day for 3–6 months.15

One of the largest series of patients with tropical sprue (n=101) was reported by Ghoshal and colleagues.3 We found that the population of patients with tropical sprue in our study had more severe features of malabsorption than those in the study by Ghoshal et al. (Hb, 8.6 vs. 10.4; P=0.0001; proportion of patients with pedal edema, 30% vs. 12%, P=0.001; with stomatitis: 42% vs. 10%, P=0.0001). Median duration of illness was shorter in our study (5.5 months vs. 24 months). Our population also had more marked histological findings like villous atrophy (51% vs. 32%, P=0.009) and intraepithelial lymphocytosis (89% vs. 51%, P=0.0001) compared to that in the study by Ghoshal et al.

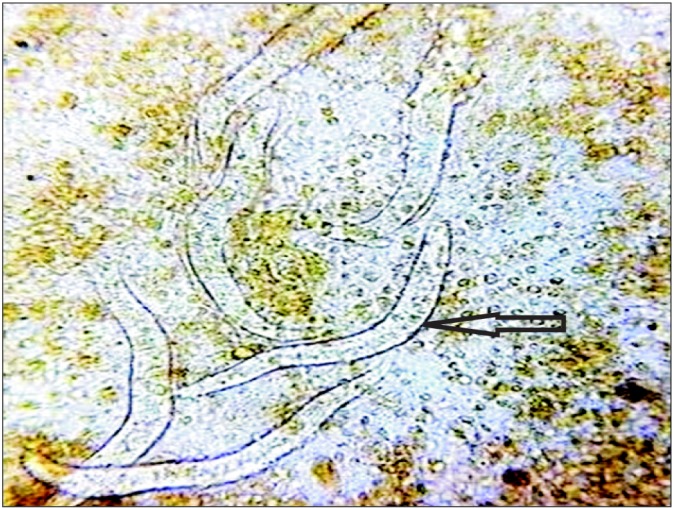

Cryptosporidium causes diarrhea by impairing glucosestimulated sodium and water absorption, increasing chloride secretion and by an enterotoxin.1718 Microsporidium causes diarrhea and malabsorption by lactase deficiency and villous surface reduction.19 Giardia directly damages the intestinal brush border and causes epithelial cell barrier dysfunction by adhering to the epithelium of small intestine,20 but it does not invade the mucosa.21 Strongyloides damages the villous surface and causes protein losing enteropathy.22 Protracted cryptosporidial and microsporidial infection are usually seen in patients with underlying immunodeficiency, especially HIV seropositivity.23 However, our study highlighted the fact that chronic infection with these organisms can occur in a significant proportion of immunocompetent hosts as well (five of six cases of cryptosporidia, three of five cases of microsporidia). Only one patient with giardiasis had low levels of Ig. Both patients with strongyloides hyperinfection had a risk factor: one had HTLV-1 infection and the other had long-term steroid intake (Fig. 5).

Our study is one of the largest series of patients with malabsorption in recent years. Though our institute gets referral patients from different parts of the country, the majority of patients belonged to western India only. This was a limitation of our study.

In conclusion, tropical sprue and parasitic disease still account for more than half of the cases of chronic small bowel diarrhea with malabsorption. Severe diarrhea, florid malabsorption (especially B12 deficiency) and mucosal damage on histology indicate tropical sprue, while presence of more upper GI symptoms indicates parasitic infections. This clinical distinction can be helpful in instituting empirical antiparasitic therapy in patients with negative stool and duodenal biopsy reports.

References

1. Farthing MJ. Tropical malabsorption. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2002; 13:221–231. PMID: 12465593.

2. Murray JA, Rubio-Tapia A. Diarrhoea due to small bowel diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012; 26:581–600. PMID: 23384804.

3. Ghoshal UC, Mehrotra M, Kumar S, et al. Spectrum of malabsorption syndrome among adults & factors differentiating celiac disease & tropical malabsorption. Indian J Med Res. 2012; 136:451–459. PMID: 23041739.

4. Yadav P, Das P, Mirdha BR, et al. Current spectrum of malabsorption syndrome in adults in India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011; 30:22–28. PMID: 21369836.

5. Thakur B, Mishra P, Desai N, Thakur S, Alexander J, Sawant P. Profile of chronic small-bowel diarrhea in adults in Western India: a hospital-based study. Trop Gastroenterol. 2006; 27:84–86. PMID: 17089618.

6. Dutta AK, Balekuduru A, Chacko A. Spectrum of malabsorption in India - tropical sprue is still the leader. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011; 59:420–422. PMID: 22315745.

7. Marsh MN, Crowe PT. Morphology of the mucosal lesion in gluten sensitivity. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1995; 9:273–293. PMID: 7549028.

8. Kapoor VK. Abdominal tuberculosis. Postgrad Med J. 1998; 74:459–467. PMID: 9926119.

9. Travis SP, Stange EF, Lémann M, et al. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: current management. Gut. 2006; 55(Suppl 1):i16–i35. PMID: 16481629.

10. Ramakrishna BS. Malabsorption syndrome in India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1996; 15:135–141. PMID: 8916578.

11. Klipstein FA, Baker SJ. Regarding the definition of tropical sprue. Gastroenterology. 1970; 58:717–721. PMID: 5444177.

12. Mathan VI, Baker SJ. Epidemic tropical sprue and other epidemics of diarrhea in South Indian villages. Am J Clin Nutr. 1968; 21:1077–1087. PMID: 5675846.

13. Mathan M, Mathan VI, Baker SJ. An electron-microscopic study of jejunal mucosal morphology in control subjects and in patients with tropical sprue in southern India. Gastroenterology. 1975; 68:17–32. PMID: 1116658.

14. Ghoshal UC, Kumar S, Misra A, Choudhuri G. Pathogenesis of tropical sprue: a pilot study of antroduodenal manometry, duodenocaecal transit time & fat-induced ileal brake. Indian J Med Res. 2013; 137:63–72. PMID: 23481053.

15. Nath SK. Tropical sprue. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005; 7:343–349. PMID: 16168231.

16. Ramakrishna BS, Venkataraman S, Mukhopadhya A. Tropical malabsorption. Postgrad Med J. 2006; 82:779–787. PMID: 17148698.

17. Moore R, Tzipori S, Griffiths JK, Johnson K, De Montigny L, Lomakina I. Temporal changes in permeability and structure of piglet ileum after site-specific infection by Cryptosporidium parvum. Gastroenterology. 1995; 108:1030–1039. PMID: 7698569.

18. Navin TR, Juranek DD. Cryptosporidiosis: clinical, epidemiologic, and parasitologic review. Rev Infect Dis. 1984; 6:313–327. PMID: 6377439.

19. Schmidt W, Schneider T, Heise W, et al. Mucosal abnormalities in microsporidiosis. AIDS. 1997; 11:1589–1594. PMID: 9365763.

20. Buret AG. Pathophysiology of enteric infections with Giardia duodenalius. Parasite. 2008; 15:261–265. PMID: 18814692.

21. Oberhuber G, Kastner N, Stolte M. Giardiasis: a histologic analysis of 567 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997; 32:48–51. PMID: 9018766.

22. Sullivan PB, Lunn PG, Northrop-Clewes CA, Farthing MJ. Parasitic infection of the gut and protein-losing enteropathy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992; 15:404–407. PMID: 1469520.

23. Didier ES, Weiss LM. Microsporidiosis: not just in AIDS patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011; 24:490–495. PMID: 21844802.

Fig. 1

Graph showing the etiological spectrum of chronic small bowel diarrhea with malabsorption. Total 203 patients were included in the study. Note that one patient with cryptospora and one patient with microspora also had underlying human immunodeficiency virus, while one patient with microspora also had hypogammaglobulinemia. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SIBO, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Fig. 2

Receiver operating characteristic curve of mean corpuscular volume (MCV) that differentiates tropical sprue from parasitic infections, (area under the curve, 0.869). An MCV more than 91 fL can best differentiate tropical sprue from parasitic infections with 85.7% sensitivity and 80% specificity.

Fig. 3

Receiver operating characteristic curve of degree of weight loss that differentiates tropical sprue from parasitic infections, (area under the curve, 0.774). Weight loss of more than 7.5 kg can differentiate tropical sprue from parasitic infections with 64.3% sensitivity and 80% specificity.

Fig. 4

Duodenal biopsy of a patient with tropical sprue. Partial villous atrophy (arrow) and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the lamina propria (asterisk) are visible. The crypt to villous ratio is almost 1:1 (H&E, ×20).

Fig. 5

Stool microscopic examination after wet mount showing multiple larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis (arrow).

Table 1

Demographic, Clinical, Laboratory and Endoscopic Parameters of Patients With Tropical Sprue and Parasitic Diseases

Values are presented as mean±SD, median (interquartile range) or n (%).

Normal range of various parameters: Hb, >11 g/dL; WBC count, 4,000–11,000/mm3; platelet counts, 1.5–4.5 lakh/mm3; MCV, 80–96; serum calcium, 9–11 mg/dL; serum albumin, 3.5–5.5 g/dL; serum cholesterol, <200 mg/dL; stool fat, >10 droplet/high powered field.

GI, gastrointestinal; Hb, hemoglobin; WBC, white blood cells; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; USG, ultrasonography.

Table 2

Factors Differentiating Tropical Sprue From Parasitic Infections on Multivariate Analysis

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download