Abstract

Background/Aims

Antibiotic usage and increasingly aging populations have led to increased incidence of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in worldwide. Recent studies in Korea have also reported increasing CDI incidence; however, there have been no reports on the long-term outcomes of CDI. We therefore investigated the long-term clinical outcomes of patients with CDI, including delayed recurrence, associated risk factors and mortality.

Methods

Hospitalized patients diagnosed with CDI at Seoul Paik Hospital between January 2007 and December 2008 were included. Their medical records were retrospectively investigated. 'Delayed recurrence' was defined as a relapse 8 weeks after a successful initial treatment. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify risk factors for the delayed recurrence. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to analyze mortality rates.

Results

A total of 120 patients were enrolled; among them, 87 were followed-up for at least 1 year, with a mean follow-up period of 34.1±25.1 months. Delayed recurrence was observed in 17 patients (19.5%), and significant risk factors were age (over 70 years, P=0.049), nasogastric tube insertion (P=0.008), and proton pump inhibitor or H2-blocker treatments (P=0.028). The 12- and 24-month mortality rates were 24.6% and 32.5%, respectively. No deaths were directly attributed to CDI.

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a major cause of diarrhea in hospitalized patients. CDI incidence has been increasing owing to increase of elderly patients with comorbidities as well as the use of antibiotics, including newly developed quinolone and cephalosporin.1,2,3 Furthermore, recent reports of increasing CDI treatment failures and recurrence rates2,4 as well as severe infections resulting in death and various complications5,6,7 have raised concerns regarding the association with hypervirulent strains (e.g., BI/NAP1/ribotype 027).8,9,10 Despite increased treatment failures, CDI treatment continues to have a high primary treatment success rate of over 80%4,11 but reports of recurrent cases making recurrence an important issue for severe chronic patients and elderly patients.

According to the national wide multi-center research by IBD research group of Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases (KASID), 17.2 CDI cases per 10,000 hospitalized patients occurred in 2004, increasing to 27.4 cases per 10,000 in 2008, a 1.6 fold increase in 5 years.12 In a single center study, Lee et al., reported a drastic increase of CDI from 2003 to 2008, from 15 CDI cases per 10,000 hospitalized patients in 2003 to 18, 36, 101, 61, and 71 cases in 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008 respectively.13 Along with the more experiences of CDI, new clinical outcomes have been reported, such as CDI recurrence rate14,15,16 and hypervirulent strains in Korea.17,18

The reported CDI recurrence rates vary by different studies, but approximately 15-30% of patients experience recurrence within 8 weeks; the second recurrence rate among patients with the first recurrence has been reported to be 40%. Lastly, the infection recurrence rate for patients with at least twice CDI recurrences is approximately 45-65%.19,20,21,22,23,24 Up to 28% of patients experienced CDI recurrence within 90 days of treatment.25 The CDI recurrence rates in Korea are still relatively low (8.9%) compared to other western countries.12 However, these incidence rates only include early CDI recurrences, within 8 weeks of treatment; thus, the long-term recurrence rate through clinical observations remains unknown.

We have previously reported CDI incidence and recurrence rates of CDI at a single center,13 but the results were limited, reporting only early recurrence rate within 8 weeks of treatment; thus, it was unclear which chronic repetitive aspects of CDI recurrence which is recent concern. We therefore investigated patients recently treated for CDI, their long-term recurrence rates and clinical progress, thereby contributing to a better understanding of the clinical aspects of chronic CDI.

Patients aged 18 years or older hospitalized at Seoul Paik Hospital diagnosed with CDI between January 2007 and December 2008 were included in this study. Patient medical records and examination results including age, sex, duration of hospital stay, intensive care unit admission, nasogastric tube insertion, underlying diseases, diarrhea, antibiotics used prior to CDI diagnosis, and serum albumin levels at diagnosis were retrospectively investigated. Patient deaths and CDI recurrence after successful treatment were also investigated. The study protocol and consent form exemption were approved by the clinical study committee of Seoul Paik Hospital.

CDI was diagnosed based on the following criteria: patients passed soft stools more than twice daily for 2 days or 6 times per 36 hours since admission, or had diarrhea. The patients need fulfill one or more; (1) stool samples positive for either C. difficile toxin A or B or identification of C. difficile in the stool, or (2) specific pseudomembranous colitis observed via lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. CDI recurrence was defined as a CDI relapse diagnosed using the above criteria, with diarrhea accompanying fever or abdominal pain after successful treatment. Recurrence diagnosed within 8 weeks of an initial successful treatment was defined as 'early recurrence'; cases diagnosed after more than 8 weeks were considered 'delayed recurrence'.

In order to detect C. difficile toxins, enzyme-linked fluorescent based VIDAS® C. difficile Toxin A & B (CDAB) were utilized. Based on the manufacture's instruction, a patient was considered positive, equivocal, and negative if relative fluorescence value (RFV) is higher than 1, in between 0.4-1.0, and lower than 0.4, respectively.

C. difficile was cultured by inoculation of patient diarrhea samples on cycloserine cefoxitin fructose agar and cultured for 48-72 hours under anaerobic conditions. Suspected strains were identified by spore staining and using a Vitek ANA anaerobic bacteria identification card (bioMérieux, France).

Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows (Version 18.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Frequency, percentile, and mean of patient characteristics were analyzed. Risk factors of early recurrence and mortality in a total of 120 cases were analyzed by using multivariate logistic regression analysis. The percentage of delayed recurrence was calculated for 87 patients who were able to be evaluated for clinical progress and survival/mortality after 1 year. The risk factors for delayed recurrence were investigated by performing multivariate logistic regression analysis. Lastly, recurrence and mortality rates of patients with CDI were depicted on a Kaplan-Meier curve.

A total of 120 patients were diagnosed with CDI at Seoul Paik Hospital over 2 years (January 2007 through December 2008). The mean follow-up period was 28.2±25.6 months (0.3-66.3 months); after 1 year, clinical progress and survival/death were confirmed in 87 patients (72.5%). The mean follow-up period for these 87 patients was 34.1±25.1 months (0.5-66.3 months) while the mean period for the remaining patients was 3.6±3.2 months.

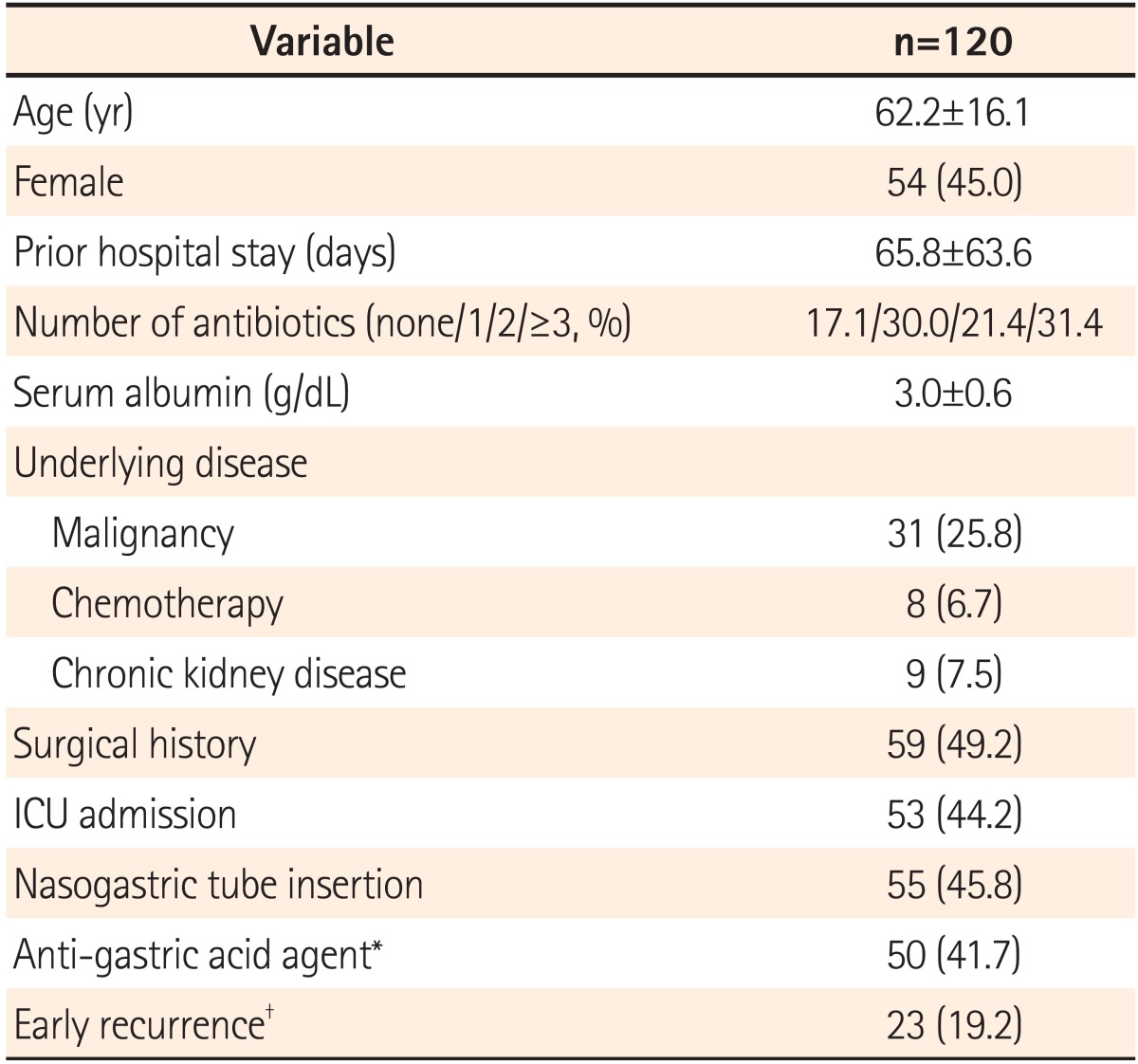

The mean age of patients with CDI was 62.2±16.1 years (18-92 years) and there were 66 male and 54 female patients (55% and 45%, respectively). When diagnosed, the mean hospitalization period was 65.8±63.6 days. Thirty-one patients were diagnosed with malignant tumors (25.8%), and 8 received chemotherapy within 1 month (6.7%). Nine patients were treated for chronic kidney disease (7.5%) and 53 patients received treatment in the intensive care unit (44.2%). Fifty-five (45.8%) and 50 patients (41.7%) had nasogastric tube insertion and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or H2-blocker treatments, respectively. Of surgery patients (59 patients, 49.2%), 32 had gastrointestinal operations (Table 1).

Prior to the CDI diagnosis, 17.1% of patients had not received antibiotic treatments, while 30.0%, 21.4%, and 31.4% of patients had been previously prescribed 1, 2, or more than 2 antibiotics, respectively. The mean antibiotic treatment period was 15.5±14.7 days. Antibiotics suspected of inducing CDI, including redundant combinations, were cephalosporin (61.7%), quinolone (39.2%), carbapenem (22.5%), aminoglycoside (17.5%), penicillin (9.2%), and others (14.2%); the cephalosporin class was most prevalent.

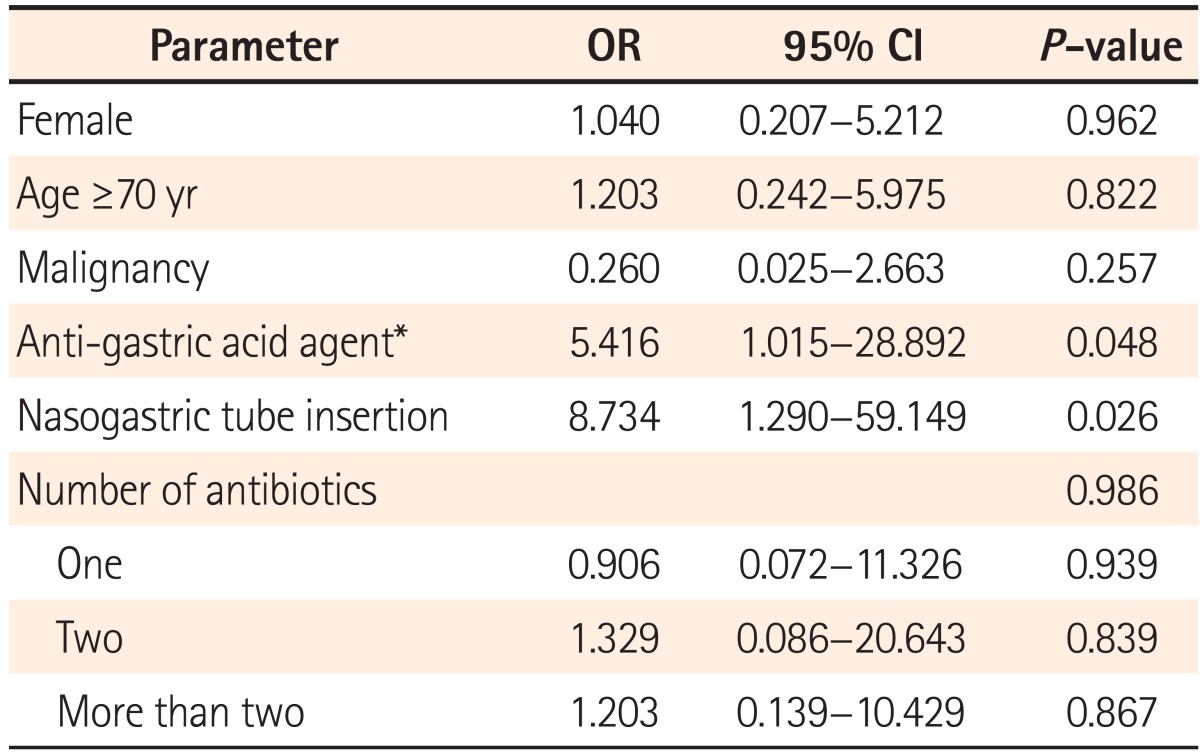

After successful CDI treatment, there were 23 cases of early

recurrence (19.2%), within 8 weeks of treatment end. Six cases were reported within 2 weeks of primary treatment, while 7 and 10 cases were reported between 2 to 4 weeks and 4 to 8 weeks, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression revealed nasogastric tube insertion (P=0.026) and PPI or H2-blocker treatment (P=0.048) to be risk factors of early recurrence, whereas age, sex, underlying diseases including malignant tumors, number of antibiotics, and duration of antibiotic treatment did not influence the early recurrence rate (Table 2).

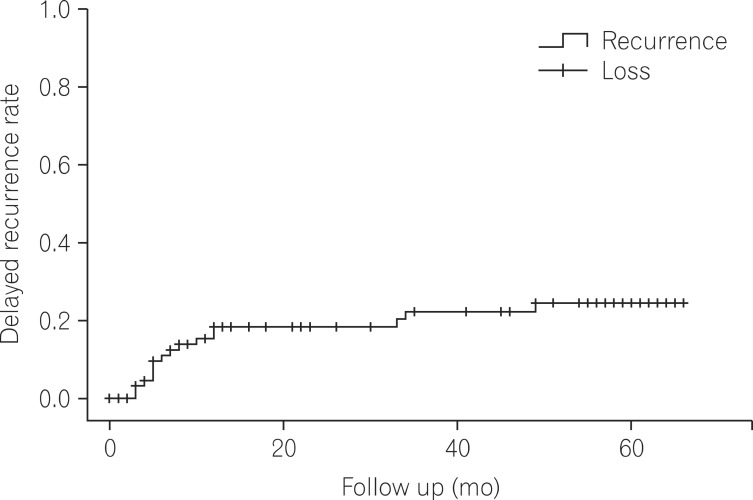

Among 87 patients available for survival/death and clinical follow-up 1 year after CDI diagnosis, there were 17 cases (19.5%) of delayed recurrence 8 weeks after successful treatment. Kaplan-Meier curve analysis showed a recurrence rate of 31% after 60 months (Fig. 1). In particular, of 19 early recurrence cases, 8 re-occurred after 8 weeks, a recurrence rate 42.1% among patients with early recurrence, a finding comparable to previous reports.20,21,24

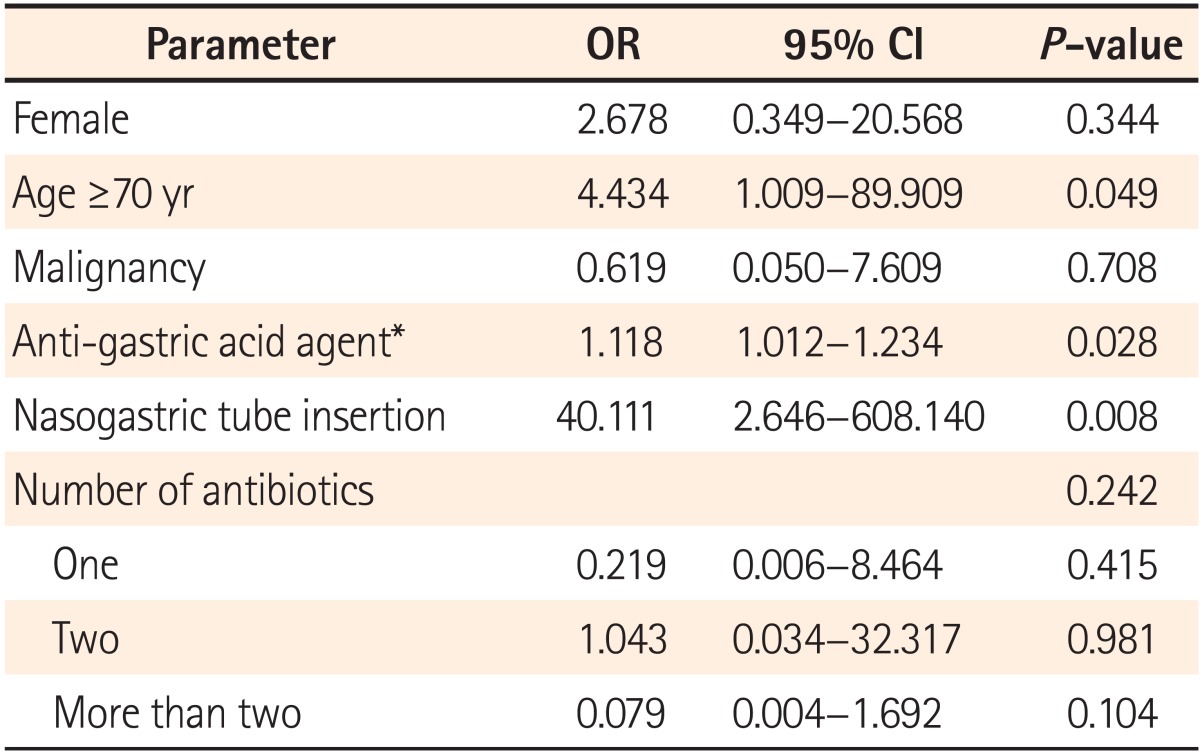

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, significant risk factors for delayed recurrence included age (more than 70 years, OR 4.434, P=0.049), nasogastric tube insertion (OR 40.111, P=0.008), and PPI or H2-blocker treatment (OR 1.118, P=0.028). Eleven patients were administered PPI medication, but PPI medication did not show statistically significant association. In addition, a history of surgery, underlying diseases, number of antibiotics, medication duration, and hospitalization period did not influence the rate of delayed CDI recurrence (Table 3). These results do not agree with other reports.15,16,26,27

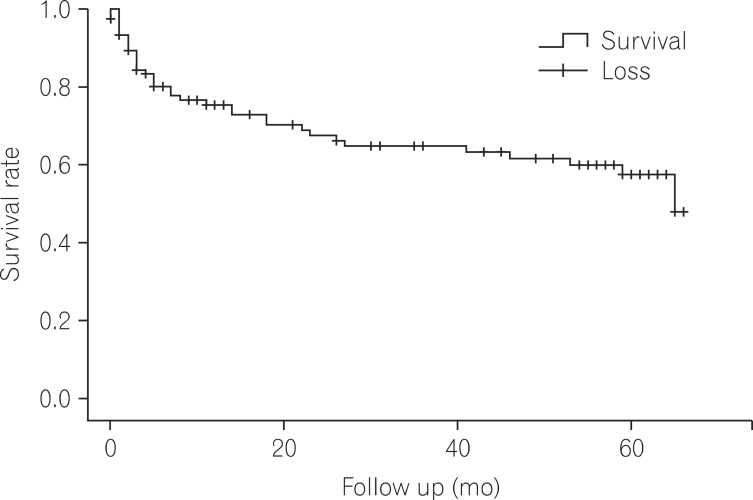

The survival rate of 120 cases of CDI patients were 75.4%, 67.5%, and 47.9% in 12 months, 24 months, and five years. During the hospitalization, there were 20 cases of deaths after the diagnosis albeit any deaths were not definitely attributed to CDI (Fig. 2). A total of 40 deaths were confirmed.

Among these deaths, 10 and 7 patients had underlying malignant tumors and chronic kidney disease, respectively. A surgical history prior to CDI diagnosis was reported in 17 patients (10 patients who underwent gastrointestinal tract surgery). Twenty-five patients who died had nasogastric tubes, and 21 and 8 patients had been treated in the intensive care unit and had early CDI recurrence, respectively. Among these clinical features, low serum albumin level was the only significant risk factor for death (P=0.026).

Causes of death included sepsis (10 patients), pneumonia (7 patients), tuberculosis (1 patient), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (1 patient), hepatorenal syndrome (1 patient), stroke (2 patients), ventricular tachycardia (1 patient), terminal cancer (6 patients: hepatic cancer, 1 patient; lung cancer, 1 patient; gastric cancer, 2 patients; lymphoma, 2 patients), gastrointestinal tract bleeding (3 patients), and unknown reasons (8 patients). Among unknown causes of death, fever and diarrhea also occurred in 2 patients, raising the possibility of death caused by CDI.

In western countries, outbreaks of hypervirulent CDI strains (BI/NAP1/ribotype 027) have been reported since 20028 and its mortality rate has been increasing recently.28,29 Particularly, in Quebec Canada, there was a five-fold increase in CDI between 1994 and 2003 along with noticeable increment of severe infections accompanying toxic megacolon, shock, and perforation.28,29 Similarly in Korea, it has been reported for critical pseudomembranous colitis induced by hypervirulent strains (BI/NAP1/ribotype 027)17; in following epidemiological studies, the detection rate for such hypervirulent strains was 0.6% but their clinical significance is still unclear.18,30

The CDI recurrence rate after successful treatment is relatively high (15-30%), and it is more likely to recur when patients had previously experienced recurrence (45-65%).20,21,24 Musher et al., reported a long-term CDI recurrence rate of up to 28% among patients with no relapse within 90 days of initial treatment, indicating that chronic CDI recurrence may be an important health care issue in the future.25

The CDI recurrence rate in Korea was reported to be 10.8-21.4%;14,31 however, these incidence rates measure only early recurrence, within 8 weeks of treatment. Therefore, the long-term recurrence rates remain unknown. In this regard, the present study is significant because we investigated not only the recurrence rate of CDI within 8 weeks of treatment (19.2%) but we also measured the delayed recurrence rate beyond 8 weeks after treatment (19.5%) via long-term clinical observations (mean, 34.1 months), although the study was performed in a single institution. In addition, we found a repeated recurrence of 42.1%, a result in agreement with other reports.19,24

Potential recurrence mechanisms for CDI relapse include incomplete eradication of C. difficile or re-infection with new C. difficile stains. In addition, other known CDI recurrence trigger conditions include: (1) patients older than 65 years of age, (2) continuous antibiotic usage, (3) failure to provide proper treatment, and (4) suppressed patient immune systems.32,33,34,35 However, re-infection with new strains is believed to be mainly responsible for CDI recurrence (48-75%).14,34,35,36 In this respect, it is meaningful that nasogastric tube insertion increases the risk of CDI up to 9-fold as manipulation of contaminated instruments can transfer C. difficile strains from hospital environments.37 The results of this study reinforce these previous findings; specifically, CDI recurrence 8 weeks after treatment (i.e., delayed recurrence) was significantly associated with age (older than 70 years), medication (PPI or H2-blocker), and nasogastric tube insertion.

In our study, both of delayed recurrence and 5-year recurrence by Kaplan-Meier analysis showed high recurrence rates (19.5% and 31%, respectively). This finding emphasizes the need to develop effective treatments for repetitive CDI recurrence. When CDI recurs, the initial antibiotics are typically re-administered if they were effective against the first infection since antibiotic resistances (e.g., metronidazole and vancomycin) are not common in Korea. However, for cases of repeated recurrence (more than twice), long-term administration of low doses of vancomycin following full dose vancomycin therapy, with or without pulse therapy has been suggested.2 In addition to standard antibiotics, non-absorbing toxin-conjugating agents (e.g., cholestyramine) are intended to facilitate excretion of C. difficile toxins. In addition, oral administration of probiotics may speed recovery of disrupted intestinal microflora. Recently, fecal microbiota transplantation showed a very high success rate (92%) and low recurrence rate (4%), making it a promising alternative to conventional treatments.24,38

Musher et al. addressed the significance of chronic CDI recurrence and raised the possibility that CDI could be utilized as a prognostic indicator given the high mortality (34%) 6 months after diagnosis.25 In the present study, the mortality rate among patients diagnosed with CDI was 24.6%, 32.5%, and 52.1% after 12 months, 24 months, and 5 years after diagnosis, that cannot be easily ignored. Although no deaths were directly attributed to CDI, it is regarded as a strong prognostic indicator for deaths from other underlying diseases.

At the time when chronic CDI recurrence has been emerging as a serious global problem, this study is meaningful as it is the first study, to our knowledge, to shed further light on clinical aspects of CDI through long-term observation in Korea. In particular, the delayed recurrence rate was found to be noticeably high, warranting development of novel methods to resolve the issue. Basically, unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be avoided and more emphasis should be placed on hygiene management such as washing hands. In addition, more active preventive measurements should be discussed; for instance, an aseptic method for nasogastric tube insertion might be worthwhile to consider for patients with a history of CDI.14 Lastly, additional investigations are needed to distinguish if recurrence was caused by the same strain or re-infection by other strains by analyzing samples from patients with chronic recurrence. This type of analysis could also be used to identify severe CDI due to hypervirulent strains.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, we calculated the delayed CDI recurrence rate (19.5%) in 87 patients; these cases included patients who were available for follow-up 1 year after CDI treatment, or who had died. In other words, of the 87 patients, 20 patients (23.0%) died during hospitalization after CDI diagnosis; therefore, the group of 87 patients may not accurately reflect features associated with recurrence among surviving patients. Owing to this potential bias, we further investigated the delayed recurrence rate using Kaplan-Meier curve analysis and found a higher recurrence rate (31%). Secondly, because this study was conducted retrospectively in relatively small sample size (n=87), it is possible that potential risk factors were overlooked in the analysis. Furthermore, the number of CDI deaths might be underestimated because analyses for hypervirulent strains have not yet been performed.

In conclusion, in this study, we found early recurrence (defined as relapse within 8 weeks of the treatment of CDI) and delayed recurrence rates (defined as relapse after 8 weeks of the treatment of CDI) of 19.2% and 19.5%, respectively. The delayed recurrence rate for patients who had experienced early recurrence was particularly high (42.1%). The mortality rate is also high at 2 years after CDI diagnosis (32.5%), suggesting that CDI diagnosis may be an important prognostic indicator for deaths from underlying diseases.

References

1. Ricciardi R, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD, Baxter NN. Increasing prevalence and severity of Clostridium difficile colitis in hospitalized patients in the United States. Arch Surg. 2007; 142:624–631. PMID: 17638799.

2. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010; 31:431–455. PMID: 20307191.

3. Lee JK, Cho JY, Kim YS, et al. Comparative value of sigmoidoscopy and stool cytotoxin-A assay for diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis. Intest Res. 2005; 3:61–67.

4. Pepin J, Alary ME, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 40:1591–1597. PMID: 15889355.

5. Jawa RS, Mercer DW. Clostridium difficile-associated infection: a disease of varying severity. Am J Surg. 2012; 204:836–842. PMID: 23036604.

6. Wenisch JM, Schmid D, Tucek G, et al. A prospective cohort study on hospital mortality due to Clostridium difficile infection. Infection. 2012; 40:479–484. PMID: 22527876.

7. Bloomfield MG, Sherwin JC, Gkrania-Klotsas E. Risk factors for mortality in Clostridium difficile infection in the general hospital population: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2012; 82:1–12. PMID: 22727824.

8. Warny M, Pepin J, Fang A, et al. Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet. 2005; 366:1079–1084. PMID: 16182895.

9. Diggs NG, Surawicz CM. Evolving concepts in Clostridium difficile colitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009; 11:400–405. PMID: 19765368.

10. Miller M, Gravel D, Mulvey M, et al. Health care-associated Clostridium difficile infection in Canada: patient age and infecting strain type are highly predictive of severe outcome and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2010; 50:194–201. PMID: 20025526.

11. Musher DM, Aslam S, Logan N, et al. Relatively poor outcome after treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis with metronidazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 40:1586–1590. PMID: 15889354.

12. Kim YS, Han DS, Kim YH, et al. Incidence and clinical features of Clostridium difficile infection in Korea: a nationwide study. Epidemiol Infect. 2013; 141:189–194. PMID: 22717061.

13. Lee JH, Lee SY, Kim YS, et al. The incidence and clinical features of Clostridium difficile infection; single center study. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010; 55:175–182. PMID: 20357528.

14. Ryu HS, Kim YS, Seo GS, Lee YM, Choi SC. Risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Intest Res. 2012; 10:176–182.

15. Choi HK, Kim KH, Lee SH, Lee SJ. Risk factors for recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: effect of vancomycin-resistant enterococci colonization. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:859–864. PMID: 21738336.

16. Jung KS, Park JJ, Chon YE, et al. Risk factors for treatment failure and recurrence after metronidazole treatment for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Gut Liver. 2010; 4:332–337. PMID: 20981209.

17. Tae CH, Jung SA, Song HJ, et al. The first case of antibiotic-associated colitis by Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 027 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2009; 24:520–524. PMID: 19543521.

18. Kim J, Kang JO, Kim H, et al. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infections in a tertiary-care hospital in Korea. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013; 19:521–527. PMID: 22712697.

19. McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Greenberg RN, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for Clostridium difficile disease. JAMA. 1994; 271:1913–1918. PMID: 8201735.

20. McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Rubin M, Fekety R, Elmer GW, Greenberg RN. Recurrent Clostridium difficile disease: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999; 20:43–50. PMID: 9927265.

21. Gerding DN. Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000; 250:127–139. PMID: 10981361.

22. Barbut F, Richard A, Hamadi K, Chomette V, Burghoffer B, Petit JC. Epidemiology of recurrences or reinfections of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2000; 38:2386–2388. PMID: 10835010.

23. Bauer MP, Notermans DW, van Benthem BH, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in Europe: a hospital-based survey. Lancet. 2011; 377:63–73. PMID: 21084111.

24. Seo GS. Clostridium difficile infection: what's new? Intest Res. 2013; 11:1–13.

25. Musher DM, Nuila F, Logan N. The long-term outcome of treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45:523–524. PMID: 17638211.

26. Garey KW, Sethi S, Yadav Y, DuPont HL. Meta-analysis to assess risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect. 2008; 70:298–304. PMID: 18951661.

27. Johnson S. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a review of risk factors, treatments, and outcomes. J Infect. 2009; 58:403–410. PMID: 19394704.

28. Pepin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004; 171:466–472. PMID: 15337727.

29. O'Connor JR, Johnson S, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection caused by the epidemic BI/NAP1/027 strain. Gastroenterology. 2009; 136:1913–1924. PMID: 19457419.

30. Kim H, Jeong SH, Roh KH, et al. Investigation of toxin gene diversity, molecular epidemiology, and antimicrobial resistance of Clostridium difficile isolated from 12 hospitals in South Korea. Korean J Lab Med. 2010; 30:491–497. PMID: 20890081.

31. Kim J, Pai H, Seo MR, Kang JO. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Clostridium difficile infection in a Korean tertiary hospital. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:1258–1264. PMID: 22022175.

32. Walters BA, Roberts R, Stafford R, Seneviratne E. Relapse of antibiotic associated colitis: endogenous persistence of Clostridium difficile during vancomycin therapy. Gut. 1983; 24:206–212. PMID: 6826104.

33. Tedesco FJ, Gordon D, Fortson WC. Approach to patients with multiple relapses of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985; 80:867–868. PMID: 4050760.

34. Wilcox MH, Fawley WN, Settle CD, Davidson A. Recurrence of symptoms in Clostridium difficile infection--relapse or reinfection? J Hosp Infect. 1998; 38:93–100. PMID: 9522287.

35. O'Neill GL, Beaman MH, Riley TV. Relapse versus reinfection with Clostridium difficile. Epidemiol Infect. 1991; 107:627–635. PMID: 1752311.

36. Maroo S, Lamont JT. Recurrent Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130:1311–1316. PMID: 16618421.

37. Bliss DZ, Johnson S, Savik K, Clabots CR, Willard K, Gerding DN. Acquisition of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients receiving tube feeding. Ann Intern Med. 1998; 129:1012–1019. PMID: 9867755.

38. Gough E, Shaikh H, Manges AR. Systematic review of intestinal microbiota transplantation (fecal bacteriotherapy) for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011; 53:994–1002. PMID: 22002980.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download