1. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Lee DH, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2011. Cancer Res Treat. 2014; 46:109–123. PMID:

24851102.

2. Coppede F. Epigenetic biomarkers of colorectal cancer: Focus on DNA methylation. Cancer Lett. 2014; 342:238–247. PMID:

22202641.

3. Coppede F, Lopomo A, Spisni R, Migliore L. Genetic and epigenetic biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:943–956. PMID:

24574767.

4. Marisa L, de Reynies A, Duval A, et al. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013; 10:e1001453. PMID:

23700391.

5. Tsang AH, Cheng KH, Wong AS, et al. Current and future molecular diagnostics in colorectal cancer and colorectal adenoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:3847–3857. PMID:

24744577.

6. Bogaert J, Prenen H. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014; 27:9–14. PMID:

24714764.

7. Pancione M, Remo A, Colantuoni V. Genetic and epigenetic events generate multiple pathways in colorectal cancer progression. Patholog Res Int. 2012; 2012:509348. PMID:

22888469.

8. Michor F, Iwasa Y, Lengauer C, Nowak MA. Dynamics of colorectal cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005; 15:484–493. PMID:

16055342.

9. Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998; 396:643–649. PMID:

9872311.

10. Pino MS, Chung DC. The chromosomal instability pathway in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2059–2072. PMID:

20420946.

11. Rajagopalan H, Nowak MA, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. The significance of unstable chromosomes in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003; 3:695–701. PMID:

12951588.

12. Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011; 6:479–507. PMID:

21090969.

13. Al-Sohaily S, Biankin A, Leong R, Kohonen-Corish M, Warusavitarne J. Molecular pathways in colorectal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 27:1423–1431. PMID:

22694276.

14. Legolvan MP, Taliano RJ, Resnick MB. Application of molecular techniques in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of patients with colorectal cancer: a practical approach. Hum Pathol. 2012; 43:1157–1168. PMID:

22658275.

15. Walther A, Houlston R, Tomlinson I. Association between chromosomal instability and prognosis in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2008; 57:941–950. PMID:

18364437.

16. Bardhan K, Liu K. Epigenetics and colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Cancers (Basel). 2013; 5:676–713. PMID:

24216997.

17. Armaghany T, Wilson JD, Chu Q, Mills G. Genetic alterations in colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2012; 5:19–27. PMID:

22574233.

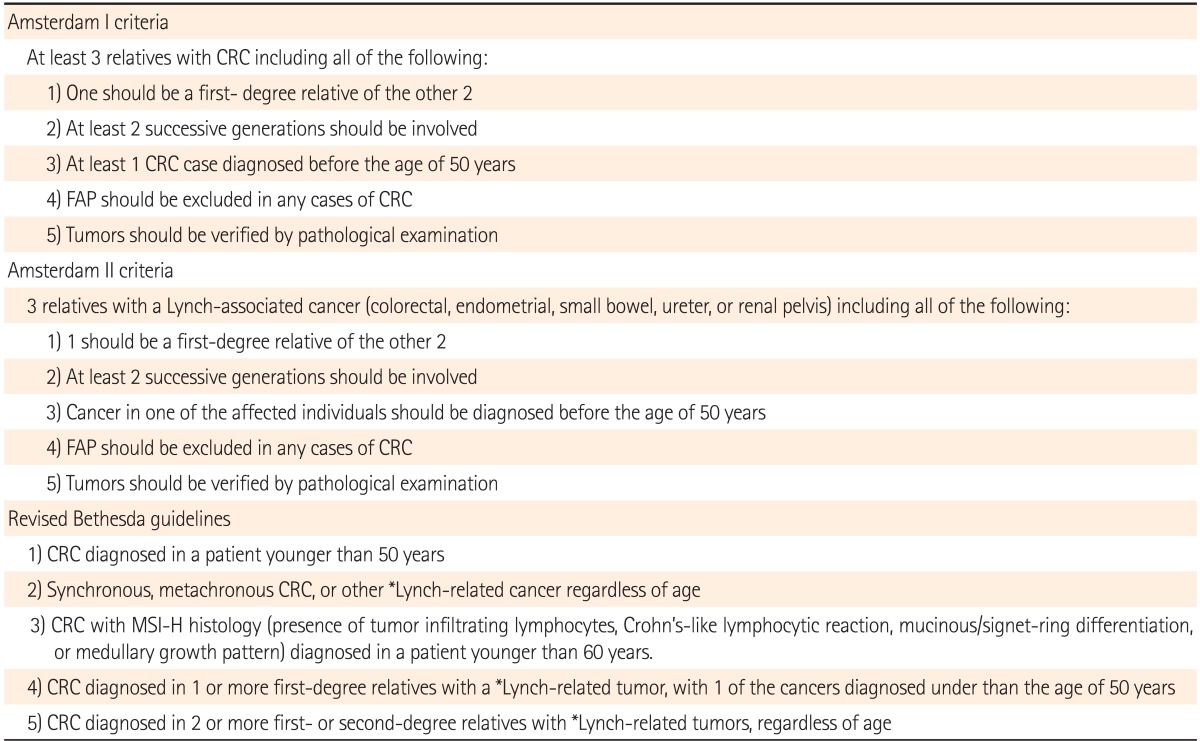

18. Umar A, Risinger JI, Hawk ET, Barrett JC. Testing guidelines for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004; 4:153–158. PMID:

14964310.

19. Narayan S, Roy D. Role of APC and DNA mismatch repair genes in the development of colorectal cancers. Mol Cancer. 2003; 2:41. PMID:

14672538.

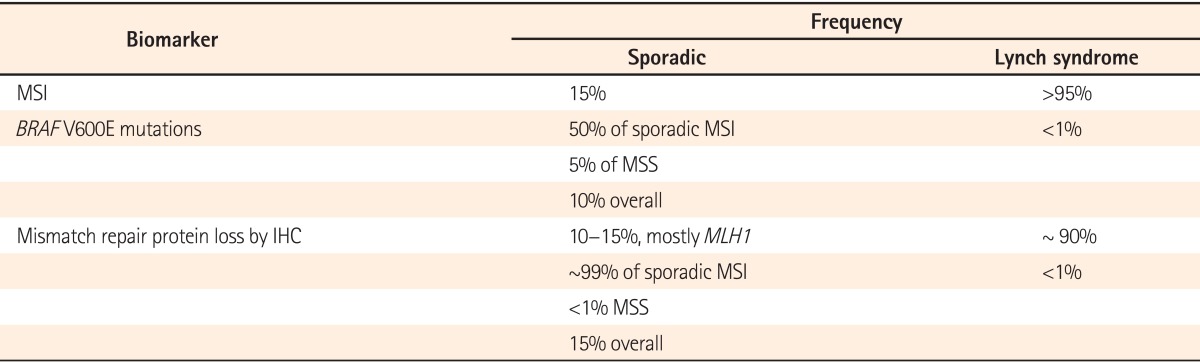

20. Kloor M, Staffa L, Ahadova A, von Knebel Doeberitz M. Clinical significance of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014; 399:23–31. PMID:

24048684.

21. Suk KT, Kim HS, Lee JH, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of colorectal cancer according to microsatellite instability. Intest Res. 2009; 7:14–21.

22. Schnekenburger M, Diederich M. Epigenetics offer new horizons for colorectal cancer prevention. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2012; 8:66–81. PMID:

22389639.

23. Wu WK, Sung JJ. MicroRNA dysregulations in gastrointestinal cancers: pathophysiological and clinical perspectives. Intest Res. 2012; 10:324–331.

24. Esteller M. Aberrant DNA methylation as a cancer-inducing mechanism. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005; 45:629–656. PMID:

15822191.

25. Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007; 8:286–298. PMID:

17339880.

26. Daniel FI, Cherubini K, Yurgel LS, de Figueiredo MA, Salum FG. The role of epigenetic transcription repression and DNA methyltransferases in cancer. Cancer. 2011; 117:677–687. PMID:

20945317.

27. Robertson KD. DNA methylation, methyltransferases, and cancer. Oncogene. 2001; 20:3139–3155. PMID:

11420731.

28. Sharp AJ, Stathaki E, Migliavacca E, et al. DNA methylation profiles of human active and inactive X chromosomes. Genome Res. 2011; 21:1592–1600. PMID:

21862626.

29. Anier K, Malinovskaja K, Aonurm-Helm A, Zharkovsky A, Kalda A. DNA methylation regulates cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010; 35:2450–2461. PMID:

20720536.

30. Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002; 3:415–428. PMID:

12042769.

31. Domingo E, Niessen RC, Oliveira C, et al. BRAF-V600E is not involved in the colorectal tumorigenesis of HNPCC in patients with functional MLH1 and MSH2 genes. Oncogene. 2005; 24:3995–3998. PMID:

15782118.

32. Rajagopalan H, Bardelli A, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE. Tumorigenesis: RAF/RAS oncogenes and mismatch-repair status. Nature. 2002; 418:934. PMID:

12198537.

33. Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990; 61:759–767. PMID:

2188735.

34. Johns LE, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001; 96:2992–3003. PMID:

11693338.

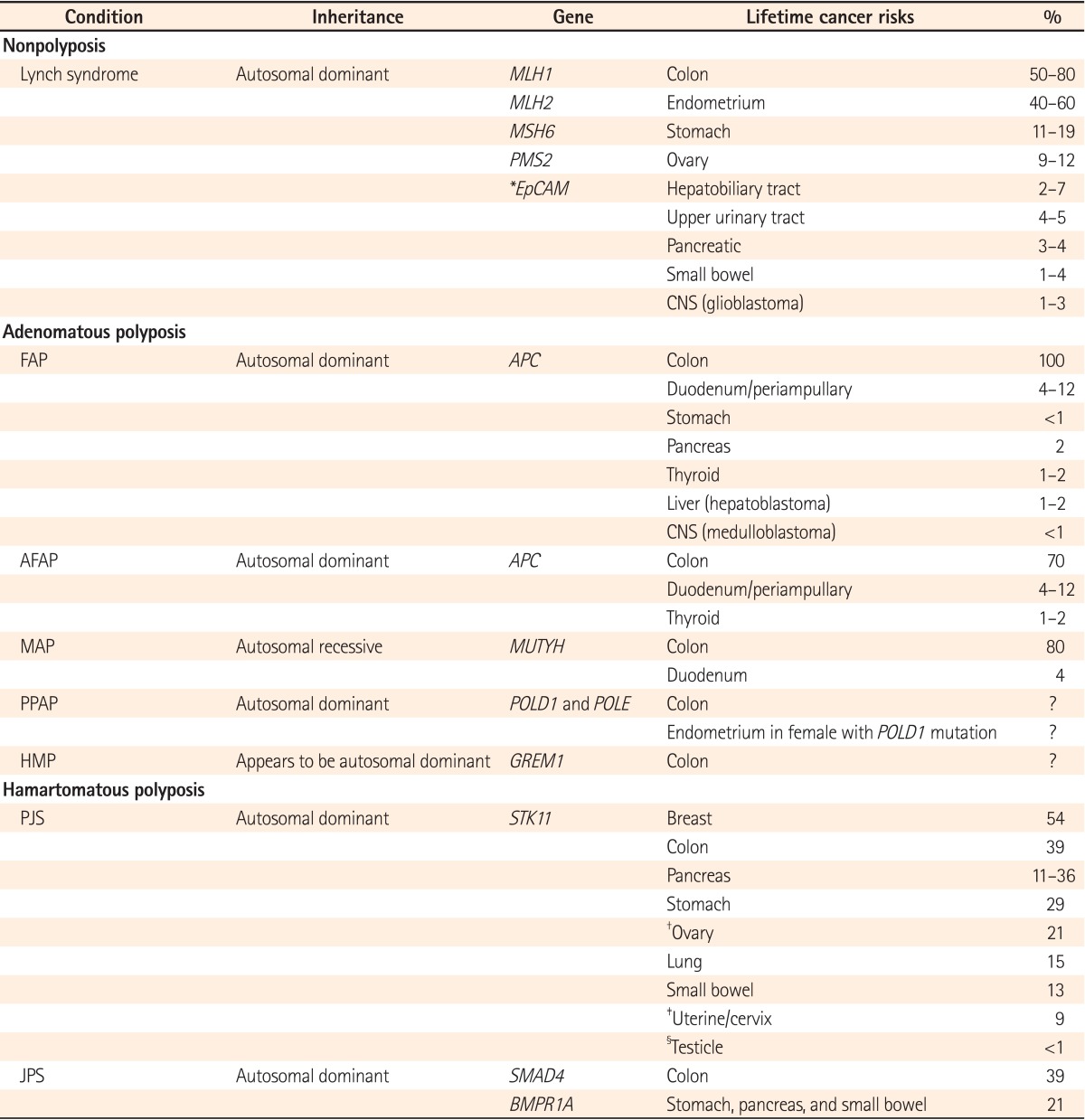

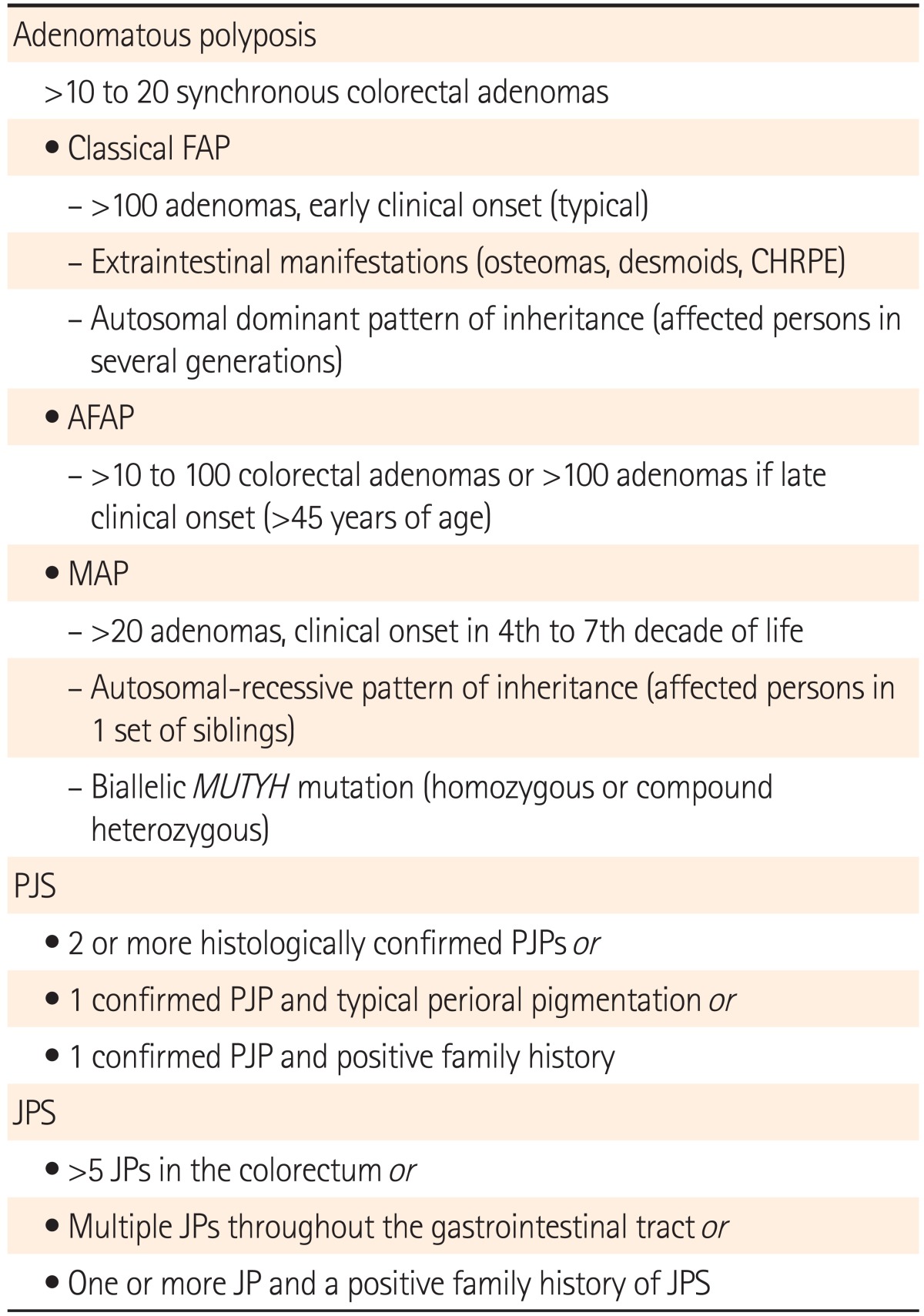

35. Gala M, Chung DC. Hereditary colon cancer syndromes. Semin Oncol. 2011; 38:490–499. PMID:

21810508.

36. Jasperson KW, Tuohy TM, Neklason DW, Burt RW. Hereditary and familial colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2044–2058. PMID:

20420945.

37. Hampel H, Frankel WL, Martin E, et al. Feasibility of screening for Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:5783–5788. PMID:

18809606.

38. Boland CR, Troncale FJ. Familial colonic cancer without antecedent polyposis. Ann Intern Med. 1984; 100:700–701. PMID:

6712034.

39. Marra G, Boland CR. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: the syndrome, the genes, and historical perspectives. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995; 87:1114–1125. PMID:

7674315.

40. Bonis PA, Trikalinos TA, Chung M, et al. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 150. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: diagnostic strategies and their implications. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2007.

41. Peltomaki P. Lynch syndrome genes. Fam Cancer. 2005; 4:227–232. PMID:

16136382.

42. Kastrinos F, Stoffel EM, Balmana J, Steyerberg EW, Mercado R, Syngal S. Phenotype comparison of MLH1 and MSH2 mutation carriers in a cohort of 1,914 individuals undergoing clinical genetic testing in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008; 17:2044–2051. PMID:

18708397.

43. Kovacs ME, Papp J, Szentirmay Z, Otto S, Olah E. Deletions removing the last exon of TACSTD1 constitute a distinct class of mutations predisposing to Lynch syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2009; 30:197–203. PMID:

19177550.

44. Niessen RC, Hofstra RM, Westers H, et al. Germline hypermethylation of MLH1 and EPCAM deletions are a frequent cause of Lynch syndrome. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009; 48:737–744. PMID:

19455606.

45. Syngal S, Fox EA, Eng C, Kolodner RD, Garber JE. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical criteria for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer associated mutations in MSH2 and MLH1. J Med Genet. 2000; 37:641–645. PMID:

10978352.

46. Pritchard CC, Grady WM. Colorectal cancer molecular biology moves into clinical practice. Gut. 2011; 60:116–129. PMID:

20921207.

47. Burt RW, Leppert MF, Slattery ML, et al. Genetic testing and phenotype in a large kindred with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2004; 127:444–451. PMID:

15300576.

48. Bjork J, Akerbrant H, Iselius L, et al. Periampullary adenomas and adenocarcinomas in familial adenomatous polyposis: cumulative risks and APC gene mutations. Gastroenterology. 2001; 121:1127–1135. PMID:

11677205.

49. Bulow S, Bjork J, Christensen IJ, et al. Duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2004; 53:381–386. PMID:

14960520.

50. Dobbie Z, Spycher M, Mary JL, et al. Correlation between the development of extracolonic manifestations in FAP patients and mutations beyond codon 1403 in the APC gene. J Med Genet. 1996; 33:274–280. PMID:

8730280.

51. Nagy R, Sweet K, Eng C. Highly penetrant hereditary cancer syndromes. Oncogene. 2004; 23:6445–6470. PMID:

15322516.

52. Bisgaard ML, Fenger K, Bulow S, Niebuhr E, Mohr J. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): frequency, penetrance, and mutation rate. Hum Mutat. 1994; 3:121–125. PMID:

8199592.

53. Schreibman IR, Baker M, Amos C, McGarrity TJ. The hamartomatous polyposis syndromes: a clinical and molecular review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005; 100:476–490. PMID:

15667510.

54. Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000; 119:1447–1453. PMID:

11113065.

55. Howe JR, Mitros FA, Summers RW. The risk of gastrointestinal carcinoma in familial juvenile polyposis. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998; 5:751–756. PMID:

9869523.

56. Hemminki A, Markie D, Tomlinson I, et al. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature. 1998; 391:184–187. PMID:

9428765.

57. Howe JR, Roth S, Ringold JC, et al. Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science. 1998; 280:1086–1088. PMID:

9582123.

58. Aretz S. The differential diagnosis and surveillance of hereditary gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010; 107:163–173. PMID:

20358032.

59. Briggs S, Tomlinson I. Germline and somatic polymerase epsilon and delta mutations define a new class of hypermutated colorectal and endometrial cancers. J Pathol. 2013; 230:148–153. PMID:

23447401.

60. Church JM. Polymerase proofreading-associated polyposis: a new, dominantly inherited syndrome of hereditary colorectal cancer predisposition. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014; 57:396–397. PMID:

24509466.

61. Seshagiri S. The burden of faulty proofreading in colon cancer. Nat Genet. 2013; 45:121–122. PMID:

23358219.

62. Palles C, Cazier JB, Howarth KM, et al. Germline mutations affecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013; 45:136–144. PMID:

23263490.

63. Jaeger E, Leedham S, Lewis A, et al. Hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome is caused by a 40-kb upstream duplication that leads to increased and ectopic expression of the BMP antagonist GREM1. Nat Genet. 2012; 44:699–703. PMID:

22561515.

64. Tomlinson IP, Carvajal-Carmona LG, Dobbins SE, et al. Multiple common susceptibility variants near BMP pathway loci GREM1, BMP4, and BMP2 explain part of the missing heritability of colorectal cancer. PLoS Genet. 2011; 7:e1002105. PMID:

21655089.

65. Wakefield LM, Hill CS. Beyond TGFbeta: roles of other TGFbeta superfamily members in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013; 13:328–341. PMID:

23612460.

66. Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:609–618. PMID:

15659508.

67. Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:247–257. PMID:

12867608.

68. Bertagnolli MM, Niedzwiecki D, Compton CC, et al. Microsatellite instability predicts improved response to adjuvant therapy with irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in stage III colon cancer: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Protocol 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27:1814–1821. PMID:

19273709.

69. Fallik D, Borrini F, Boige V, et al. Microsatellite instability is a predictive factor of the tumor response to irinotecan in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2003; 63:5738–5744. PMID:

14522894.

70. Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:1408–1417. PMID:

19339720.

71. Lyseng-Williamson KA. Cetuximab: a guide to its use in combination with FOLFIRI in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in the USA. Mol Diagn Ther. 2012; 16:317–322. PMID:

23055389.

72. Xu Q, Xu AT, Zhu MM, Tong JL, Xu XT, Ran ZH. Predictive and prognostic roles of BRAF mutation in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies: a meta-analysis. J Dig Dis. 2013; 14:409–416. PMID:

23615046.

73. Leshno A, Gat-Harlap A, Arber N. Can an aspirin a day keep the colorectal cancer away? Intest Res. 2012; 10:229–234.

74. Nishihara R, Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, et al. Aspirin use and risk of colorectal cancer according to BRAF mutation status. JAMA. 2013; 309:2563–2571. PMID:

23800934.

75. Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, et al. Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367:1596–1606. PMID:

23094721.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download