Abstract

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is an uncommon benign disease that is misdiagnosed as malignancy or inflammatory bowel disease because of similarities in clinical and endoscopic manifestations. Furthermore, SRUS with ulcerative colitis (UC) is extremely rare. To date, two cases have been reported in the medical literature. We report an additional case of SRUS with UC that was misdiagnosed as rectal cancer. A 61-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with rectal bleeding. Colonoscopy showed a well-demarcated, shallow, ulcerative lesion with polypoidal growth involving the entire circumference of the rectal lumen. Findings from imaging studies, including abdominal computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT resembled those of rectal cancer. Surgical resection was performed because clinical symptoms persisted despite medical treatment and because occult rectal cancer could not be ruled out. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen revealed fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria and crypt abscesses, characteristics compatible with SRUS and UC.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is an uncommon benign disease of defecation. SRUS manifests as rectal bleeding, mucoid discharge, straining, altered bowel habits, incontinence, tenesmus, rectal prolapse, and a sensation of incomplete defecation.1,2 The endoscopic findings of SRUS show variable patterns, including hyperemic mucosa, ulceration, and polypoid lesions.3 Because of variable clinical and endoscopic manifestations, SRUS is often misdiagnosed as malignancy, IBD, chronic vascular insufficiency, and colitis cystica profunda.4 When SRUS is difficult to distinguish from malignancy, unnecessary surgery is performed.

In addition, if SRUS is accompanied by IBD, an accurate diagnosis is more difficult to achieve. To date, two cases have been recorded in the medical literature. Here we report an additional case of a 61-year-old man with coexistent SRUS and ulcerative colitis (UC), and review the literature pertaining to this condition.

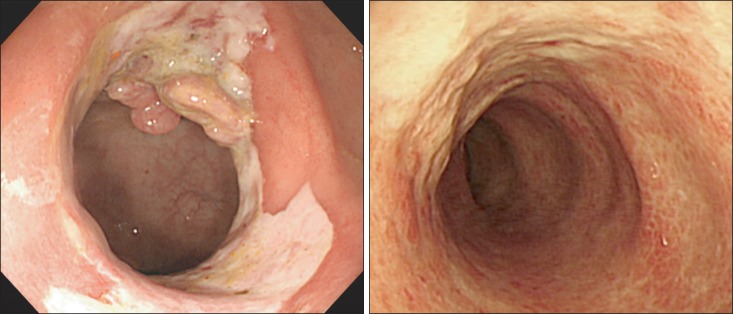

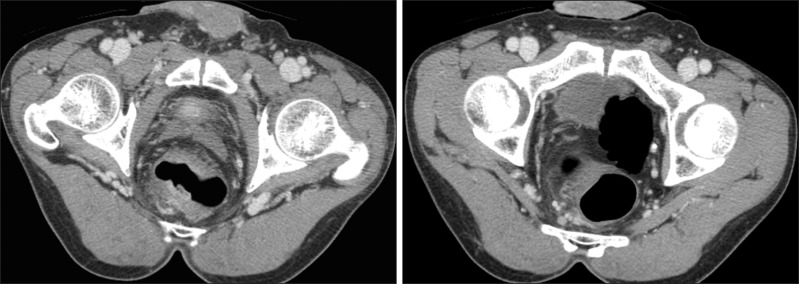

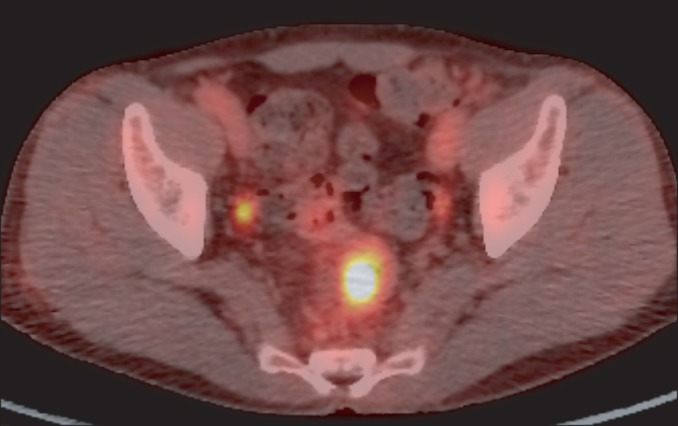

A 61-year-old man was admitted to Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (Jeonnam, Korea) with a 1-day history of rectal bleeding. He denied prior gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer diseases, use of ulcerogenic medications, or alcohol ingestion during the past year. However, the patient had experienced excessive straining with defecation, tenesmus, and frequent lower abdominal pain for 6 months. On admission, the patient was afebrile, his blood pressure and pulse rate were normal, and he appeared well nourished. No anemic conjunctiva, florid spider angioma, or hepatomegaly was present. The abdomen was nontender without ascites, the spleen tip was not palpable, and bowel sounds were normoactive. Rectal examination demonstrated the presence of clotted blood. All laboratory examination results, including complete peripheral blood cell counts, blood biochemistry, and tumor markers, were within normal range. Colonoscopy showed a well-demarcated, shallow ulcerative lesion with polypoidal growth involving the entire circumference of the lower rectal lumen. Loss of vascular pattern, edema, and mucopus coating in the distal sigmoid colon and the upper rectum were also seen (Fig. 1). Histopathological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed a chronic ulcer with granulation tissue. There was no evidence of malignancy. However, abdominal CT revealed thickening of the concentric wall with enhancement in the rectum and enlargement of the regional lymph nodes (Fig. 2). Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT revealed increased FDG uptake in the lower rectum and regional lymph nodes (Fig. 3). The imaging findings, including those from abdominal CT and FDG-PET/CT, resembled those of rectal cancer. Therefore, mucosal biopsy was repeated; the histopathological findings were similar to those of the previous biopsy. The patient underwent treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and laxatives. However, clinical symptoms, including hematochezia, persisted despite medical treatment, and occult rectal cancer could not be ruled out. Therefore, low anterior resection was performed. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen revealed fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria, thickening of the muscularis mucosa, crypt abscesses, focal gland destruction, and increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria (Fig. 4). The resected specimen was interpreted as SRUS and UC. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 7 without complications. The patient received medical treatment for UC, and he was asymptomatic at the follow-up examination.

SRUS is a poorly understood syndrome that affects men and women equally and often occurs in young adults;5 the condition has also been described in the geriatric population.6 Its pathogenesis is probably multifactorial, and most accepted causes implicate direct trauma by repetitive self-digitation and ischemic injury to the rectal mucosa.7,8 SRUS is diagnosed by a combination of clinical aspects, endoscopic presentations, and histologic findings.

SRUS usually presents with rectal bleeding and passage of mucus on defecation.1 Other symptoms are tenesmus, straining, constipation, diarrhea, incontinence, and a sensation of incomplete evacuation. The endoscopic features of SRUS vary greatly, from hyperemic mucosa to ulcerated or polypoid lesions in different numbers and sizes.9 The histologic findings of SRUS are characterized by fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria, thickened muscularis mucosa, and distortion of crypt architecture.10

SRUS is an uncommon benign disorder of defecation and is difficult to distinguish from malignancy and IBD because of variable clinical and endoscopic manifestations.11 Misdiagnosis of SRUS as malignancy can lead to unnecessary surgery. Biopsies should be performed to exclude a malignancy misdiagnosis. In our case, colonoscopic biopsy showed an ulcerative rectal mucosa and granulation tissue with no evidence of malignancy and IBD. However, the findings of abdominal CT and FDG-PET/CT resembled those of rectal cancer. Therefore, repeat mucosal biopsy was performed and histopathologic findings were similar to those of the previous biopsy.

SRUS accompanied by IBD is extremely rare, and an accurate differential diagnosis is difficult to achieve. In our case, the patient frequently experienced tenesmus and lower abdominal pain, although typical symptoms of UC such as chronic diarrhea or long-term hematochezia had not occurred. Colonoscopy showed loss of vascular pattern and presence of mucopus coating, which are symptoms different from those associated with SRUS. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen revealed findings compatible with UC. The patient was finally diagnosed with coexistence of SRUS and UC. Symptomatic improvement following initial treatment with biofeedback therapy and laxatives was not satisfactory, which made diagnosis more difficult.

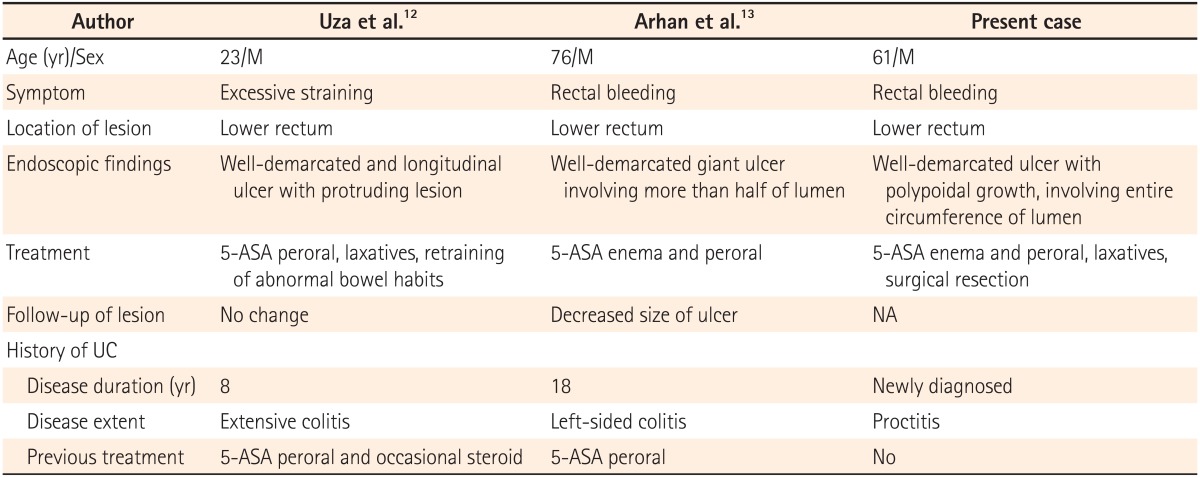

To date, only three cases of SRUS associated with UC (including the present case) have been reported in the medical literature (Table 1).12,13 The patients were men aged 23-76 years (mean age, 53.3 years). Two patients had a history of UC. In our case, we diagnosed the patient with SRUS and UC simultaneously by surgery. In two cases, excluding ours, 5-ASA was used to treat UC. The disease extent of UC varied from proctitis to pancolitis. The most common symptom was passage of blood from the rectum. In two cases, including ours, excessive straining with defecation was a possible cause of SRUS. In the endoscopic features of SRUS, all three cases showed well-demarcated, single ulcer with or without polypoid lesions in the lower rectum. Previously, endoscopic findings of SRUS revealed shallow ulcers in the majority of cases, and polypoid/nodular lesions or hyperemic mucosa in the remaining cases. All three patients received medical treatment consisting of 5-ASA, laxatives, and biofeedback therapy. At the follow-up examination, the symptoms and lesion remained unchanged or slightly improved. Furthermore, our patient was refractory to medical treatment, and occult malignancy could not be excluded with imaging studies. Therefore, surgical resection was performed. The characteristic histological findings in all three cases were fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria, thickening of the muscularis mucosa, and elongation and distortion of the crypt.

No known mechanism can link UC to the development of SRUS. In our case, it is unclear whether UC developed earlier than SRUS because atypical symptoms such as tenesmus and abdominal pain persisted for 6 months. However, the development of the solitary rectal ulcer near the UC lesion indicates a possible sequential relationship between SRUS and UC.

In conclusion, although coexistence of SRUS and UC is extremely rare, we suggest that the association between SRUS and UC may not be fortuitous. Additional studies are warranted to clarify the relationship between SRUS and UC, including underlying mechanisms responsible for their development and predisposing factors.

References

1. Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Church JM, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Milsom JW. Clinical conundrum of solitary rectal ulcer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992; 35:227–234. PMID: 1740066.

2. Ho YH, Ho JM, Parry BR, Goh HS. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: the clinical entity and anorectal physiological findings in Singapore. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995; 65:93–97. PMID: 7857237.

3. Beck DE. Surgical therapy for colitis cystica profunda and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2002; 5:231–237. PMID: 12003718.

4. Li SC, Hamilton SR. Malignant tumors in the rectum simulating solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in endoscopic biopsy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:106–112. PMID: 9422323.

5. Sharara AI, Azar C, Amr SS, Haddad M, Eloubeidi MA. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: endoscopic spectrum and review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:755–762. PMID: 16246692.

6. Chong VH, Jalihal A. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: characteristics, outcomes and predictive profiles for persistent bleeding per rectum. Singapore Med J. 2006; 47:1063–1068. PMID: 17139403.

7. Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Petras RE, et al. Clinical and pathologic factors associated with delayed diagnosis in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993; 36:146–153. PMID: 8425418.

9. Niv Y, Bat L. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome-clinical, endoscopic, and histological spectrum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986; 81:486–491. PMID: 3706271.

10. Chiang JM, Changchien CR, Chen JR. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: an endoscopic and histological presentation and literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006; 21:348–356. PMID: 16133006.

11. Saul SH, Sollenberger LC. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Its clinical and pathological underdiagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985; 9:411–421. PMID: 4091179.

12. Uza N, Nakase H, Nishimura K, Yoshida S, Kawabata K, Chiba T. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome associated with ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:355–356. PMID: 16427960.

13. Arhan M, Onal IK, Ozin Y, et al. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in association with ulcerative colitis: a case report. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010; 16:190–191. PMID: 19418566.

Fig. 1

Colonoscopic findings. Colonoscopy shows a well-demarcated, shallow ulcerative lesion with polypoid growth involving the entire circumference of the rectal lumen (A). In addition, loss of vascular pattern and the presence of mucopus coating and edema were noted (B).

Fig. 2

Abdominal CT findings. CT reveals concentric wall thickening with enhancement in the rectum (A) and enlargement of the regional lymph nodes (B).

Fig. 3

Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography/CT findings. PET/CT reveals increased FDG uptake in the rectum and regional lymph nodes.

Fig. 4

Histopathological findings of the rectum. Histopathological examination of the resected specimen reveals thickening of the muscularis mucosa and fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria (A). Crypt abscesses, focal gland destruction, and increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria are also seen (B) (H&E stain, ×100).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download