Abstract

Background/Aims

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) has been used for preoperative staging of colorectal cancer (CRC). However, the diagnostic accuracy of FDG-PET/CT for detection of lymph node or distant metastasis and its prognostic role have not been well established. We therefore evaluated the diagnostic and prognostic value of FDG-PET/CT in comparison with conventional CT for CRC.

Methods

We investigated 220 patients who underwent preoperative FDG-PET/CT and CT, followed by curative surgery for CRC. The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of FDG-PET/CT and CT for detection of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis were evaluated. In addition, we assessed the findings of FDG-PET/CT and CT according to outcomes, including cancer recurrence and cancer-related death, for evaluation of prognostic value.

Results

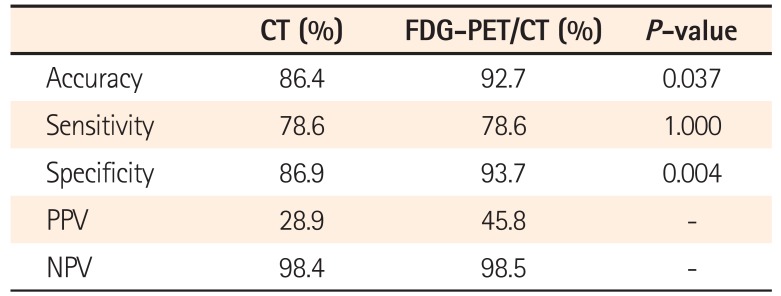

For detection of lymph node metastasis, FDG-PET/CT had a sensitivity of 44%, a specificity of 84%, and an accuracy of 67%, compared with 59%, 65%, and 62%, respectively, for CT (P=0.029, P=0.000, and P=0.022). For distant metastasis, FDG-PET/CT had a sensitivity of 79%, a specificity of 94%, and an accuracy of 93%, compared with 79%, 87%, and 86%, respectively, for CT (P=1.000, P=0.004, and P=0.037). In addition, positive findings of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis on FDG-PET/CT were associated significantly with cancer recurrence or cancer-related death (P=0.009, P=0.001, respectively).

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in males and the second most diagnosed cancer in females, accounting for over one million cases per year worldwide.1 The overall survival or disease-free survival of CRC has improved because of more accurate preoperative staging using advanced imaging technology and better treatment options, including refinements in surgical techniques and more options for chemotherapy and radiation therapy.2

Choosing and planning the appropriate therapies depend on the use of non-invasive imaging that accurately identifies the extent of disease involvement.3 Fluorine-18 (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET/CT is one of the developments of imaging technology. The primary indications for FDG-PET/CT in CRC are for staging, restaging, and detection of recurrence. The value of FDG-PET/CT for detecting recurrence and/or metastasis of CRC is well established.456 In addition, the effectiveness of FDG-PET/CT for predicting chemotherapy response has been studied.37

However, the diagnostic accuracy of FDG-PET/CT for detection of lymph node or distant metastasis has not been fully assessed, and the prognostic role of preoperative FDG-PET/CT for CRC is not well established. We therefore evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of preoperative FDG-PET/CT compared with conventional CT for CRC, and also investigated the prognostic role of FDG-PET/CT.

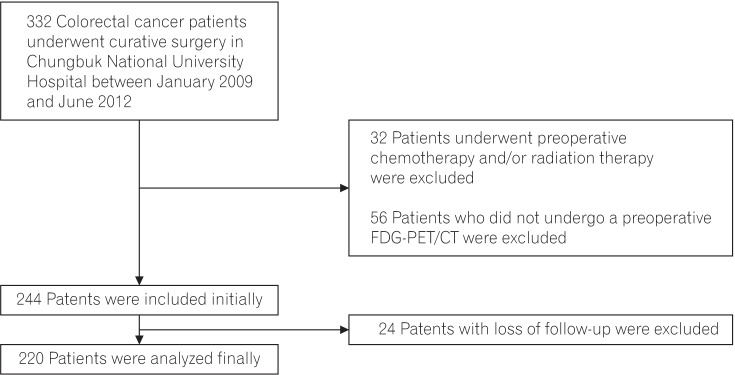

Between January 2009 and June 2012, 220 patients who underwent curative surgery for CRC in Chungbuk National University Hospital were included in this retrospective study. Preoperative whole body FDG-PET/CT, and chest and abdominopelvic contrast-enhanced CT scans were performed in each case. For all patients, pathologic staging was obtained after surgery. Patients who underwent palliative surgery or preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and patients who did not undergo preoperative FDG-PET/CT were excluded (Fig. 1). Data were obtained by review of medical records. This study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Chungbuk National University Hospital.

Patient clinical features, including age and gender, factors that could affect the accuracy of the FDG-PET/CT such as blood sugar level, and mean CEA level were collected. Operation and pathologic features such as cancer size, location, cell type, differentiation, stage, and microsatellite instability (MSI) status were also collected. Data for maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax), lymph node metastasis, and distant metastasis in FDG-PET/CT and CT were collected.

CT was performed with a 64-slice scanner (Brilliance CT; Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH, USA) and nonionic intravenous contrast material was administered at a dose of 2 mL/kg up to a maximum of 180 mL. FDG-PET/CT studies were performed on a hybrid PET/CT scanner (Discovery STE; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Patients fasted for at least 6 hours before the scan. Blood glucose levels were recorded prior to 18F-FDG administration. If the serum glucose level was greater than 200 mg/dL, the study was rescheduled. Patients were injected with 296 to 370 MBq of 18F-FDG. Imaging was performed 60 minutes later in accordance with the institutional PET protocol, including two-dimensional mode acquisition with a field of view of 15 cm. All images were reconstructed using post-emission transmission attenuation-corrected data sets.

The CT scan was reviewed by experienced radiologists in our institute; regional lymph nodes of 1 cm or larger were regarded as lymph node metastasis, and other site abnormalities interpreted as probable metastatic disease were regarded as distant metastasis. FDG-PET/CT images were interpreted using visualization and semiquantitative analysis by an experienced nuclear medicine physician, and the criterion for malignancy was accepted as 18F-FDG hypermetabolism at the site of pathological changes noted on CT, or via marked focal hypermetabolism at the physiological uptake sites. Distant metastasis in FDG-PET/CT were defined as positive or indicative of malignancy in organs other than the primary CRC site. SUVmax was calculated for all pathological lesions.

Cancer recurrence and cancer-related death were investigated by reviewing medical records or making phone calls to patients or patient's families for the assessment of prognosis.

Descriptive numerical values were reported as mean±SD and percentage. For comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and the accuracy of detection of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis by CT and FDG-PET/CT, the chi-square test and McNemar test were used. Kaplan-Meier and log-rank methods were used to analyze the prognosis for CRC. All P-values were two-sided, with P<0.05 considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

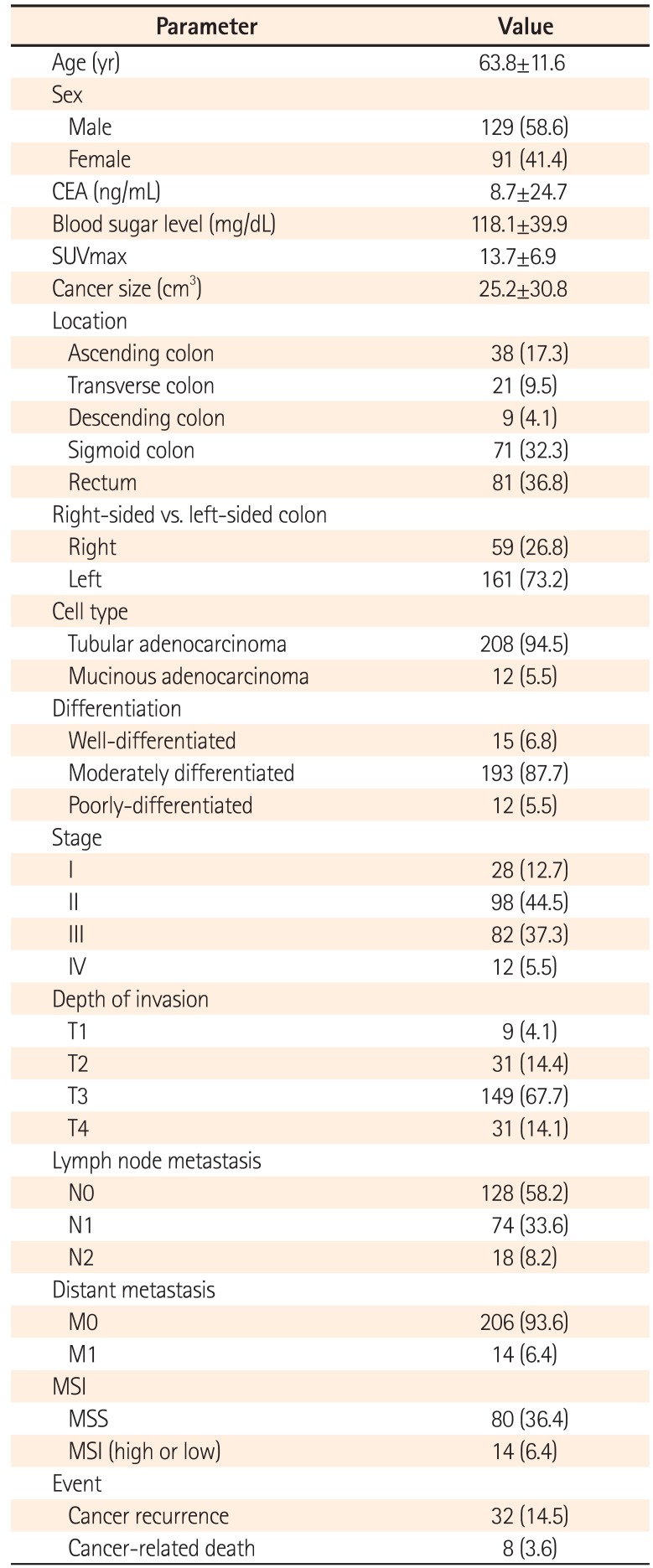

Among the 220 patients with CRC, the mean age was 63.8 years and the mean cancer size was 25.2 cm3. Left-sided colon cancer accounted for 73.2%, while right-sided cancer accounted for 26.8%. Adenocarcinoma cell type was found in 94.5% of patients, and 87.7% of these patients showed moderate differentiation. Stages II and III accounted for 81.8% of all patients. Cancer recurrence and cancer-related death occurred in 32 (14.5%) and eight (3.6%) of the patients, respectively (Table 1).

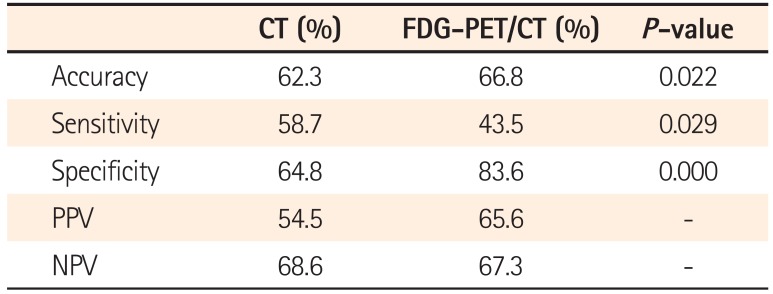

CT had significantly higher sensitivity compared to FDG-PET/CT for detection of lymph node metastasis (59% vs. 44%, P=0.029). On the other hand, FDG-PET/CT had significantly higher specificity and accuracy than CT for detection of lymph node metastasis (84% vs. 65%, P=0.000; 67% vs. 62%, P=0.022) (Table 2). In addition, FDG-PET/CT had significantly higher specificity and accuracy than CT for detection of distant metastasis (94% vs. 87%, P=0.004; 93% vs. 86%, P=0.037); however, there was no difference in sensitivity between FDG-PET/CT and CT for detection of distant metastasis (79% vs. 79%, P=1.000) (Table 3). Tumor SUVmax of FDG-PET/CT was significantly correlated with tumor size alone (P=0.001). Metastatic sites on FDG-PET/CT were liver (n=8), lung (n=8), bone (n=4), peritoneum (n=2), and other organs including spleen and kidney (n=1). However, the numbers of among organs were too small to be meaningful in statistical analysis.

Age, gender, blood glucose level, location, cell type, cancer size, CEA level, SUVmax, and MSI had no significant relationship with prognosis. Factors influencing prognosis of CRC were cell differentiation and cancer stage (P=0.020, P<0.001, respectively). In addition, positive findings for lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis on FDG-PET/CT were associated significantly with cancer recurrence or cancer-related death (P=0.009, P=0.001, respectively), whereas positive findings for lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis on CT were not associated with cancer recurrence or cancer-related death (P=0.116, P=0.120, respectively) (Figs. 2 and 3).

A number of imaging modalities are used in the preoperative staging of CRC, including CT, MRI, ultrasound imaging, and FDG-PET/CT. CT is an established method for staging CRC, and a cross-sectional imaging technique that uses X-rays provides detailed anatomical information.8 FDG-PET/CT scan is not routinely indicated and should be used to evaluate an equivocal finding on a contrast-enhanced CT scan or in patients with contraindications to intravenous contrast.9 However, according to several studies, FDG-PET/CT can be a valuable tool in accurate staging; FDG-PET/CT can aid in the management of patients with primary CRC, and can be useful for ambiguous or equivocal lesions on CT.101112 In addition, a major drawback of CT is that it does not provide functional information and hence cannot reliably discriminate between enlarged cancerous nodes and enlarged benign reactive nodes. On the other hand, FDG-PET/CT, which provides both anatomic and functional information, has been shown to be accurate in diagnosing primary colorectal tumor extension and metastasis.13 FDG-PET/CT has also been used for diagnostic staging in recurrent CRC.14 Furthermore, it has been reported to influence surgical decision-making in up to 40% of patients with documented recurrence by other imaging methods.15161718

In this study, we found that preoperative FDG-PET/CT had a higher specificity and accuracy compared to CT for detection of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis in patients with CRC. The higher specificity of FDG-PET/CT for lymph node metastasis is related to nonspecific lymph node enlargement or reactive changes.19 Frequently, CT shows inflammatory or nonspecific lymph node enlargement as a positive finding. However, these findings do not always mean true malignant lymph node metastasis. Additionally, the higher specificity of FDG-PET/CT for distant metastasis is related to liver metastasis, because the most frequent site of CRC metastasis is the liver, and FDG-PET/CT accurately identifies hepatic metastasis.202122 Thus, FDG-PET/CT can be used for accurate staging of patients with primary CRC, with higher specificity than CT. However, despite its high specificity in characterizing lymph node involvement, FDG-PET/CT had lower sensitivity than CT for regional lymph node metastasis. The higher false-negative rate for FDG-PET/CT is due to its limited spatial resolution, which makes it difficult to detect proximal lymph node metastasis from the primary tumor.23 This means that preoperative FDG-PET/CT may have low value for detecting regional lymph node metastasis surrounding a primary lesion. Additionally, FDG-PET/CT is limited by minimum detectable lesion size.24 SUV, especially in smaller lesions, is generally proportional to lesion size.25 That is why this study showed that SUVmax was significantly related to tumor size. Therefore, small lymph node metastasis can be hard to detect with FDG-PET/CT, resulting in low sensitivity of the examination. However, if the SUVmax is 2 or 3, pathological metastatic lymph nodes can frequently be seen.26 In addition, FDG-PET/CT with high specificity can help to clarify the nature of uncertain lymph nodes detected by other imaging modalities such as CT.

In our study, we evaluated the factors influencing the prognosis of CRC. Age, gender, blood glucose level, location, cell type, cancer size, CEA level, SUVmax, and MSI did not affect CRC prognosis. Factors influencing the prognosis were cell differentiation and cancer stage. Additionally, positive findings of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis on FDG-PET/CT were valuable as prognostic factors for CRC. The high prognostic impact of lymph node metastasis in CRC is well established.27 In this study, CRC staging for event-free survival was based on the imaging finding, not on final pathologic stage. CT uses size as the main criterion in the assessment of nodal involvement, although lymph node size is not an ideal indicator of metastasis and lacks accuracy.28 The accuracy of CT for detection of lymph node metastasis was 62.3% in this study, and this is why CT was not associated with event-free survival in CRC. Several studies have shown that FDG-PET/CT can be predictive of prognosis for postoperative recurrent CRC. Imdahl et al.29 showed that FDG-PET/CT has greater accuracy for staging of recurrent CRC than CT. Fernandez et al.30 showed that screening with FDG-PET/CT was associated with post-resection five-year overall survival for patients who underwent resection of hepatic metastasis from CRC. Additionally, Flanagan et al.31 reported that FDG-PET/CT was a valuable imaging tool in patients who had a rising CEA level after colorectal surgery. Because FDG-PET/CT has higher accuracy for detection of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, it can be valuable for predicting prognosis. It is notable that FDG-PET/CT, as an accurate preoperative staging method, can determine appropriate management decisions and precise prognosis in patients with CRC.

This study had several limitations, including its retrospective single-center study design and relatively short-term follow-up. Only patients who underwent preoperative FDG-PET/CT were included, and patients who underwent preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy were excluded. However, accurate pathologic staging was accomplished because all patients in our study underwent surgery, and a relatively large number of patients were enrolled and followed up.

In conclusion, this study showed that preoperative FDG-PET/CT had a higher specificity and accuracy compared to CT scan for detection of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis of CRC. In addition, positive findings of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis on FDG-PET/CT were significantly associated with poor outcome; thus, FDG-PET/CT could be useful as a prognostic tool for CRC. Additional well-powered and prospective studies are needed to validate our findings.

Notes

References

1. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011; 61:69–90. PMID: 21296855.

2. Kapse N, Goh V. Functional imaging of colorectal cancer: positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2009; 8:77–87.

3. Akhurst T, Kates TJ, Mazumdar M, et al. Recent chemotherapy reduces the sensitivity of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the detection of colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:8713–8716. PMID: 16314631.

4. Chin BB, Wahl RL. 18F-Fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the evaluation of gastrointestinal malignancies. Gut. 2003; 52(Suppl 4):iv23–iv29. PMID: 12746265.

5. Chen LB, Tong JL, Song HZ, Zhu H, Wang YC. (18)F-DG PET/CT in detection of recurrence and metastasis of colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2007; 13:5025–5029. PMID: 17854148.

6. Makis W, Kurzencwyg D, Hickeson M. 18F-FDG PET/CT superior to serum CEA in detection of colorectal cancer and its recurrence. Clin Imaging. 2013; 37:1094–1097. PMID: 23993799.

7. Li C, Lan X, Yuan H, Feng H, Xia X, Zhang Y. 18F-FDG PET predicts pathological response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with primary rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Nucl Med. 2014; 28:436–446. PMID: 24623152.

8. Brush J, Boyd K, Chappell F, et al. The value of FDG positron emission tomography/computerised tomography (PET/CT) in pre-operative staging of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2011; 15:1–192.

9. Cipe G, Ergul N, Hasbahceci M, et al. Routine use of positron-emission tomography/computed tomography for staging of primary colorectal cancer: does it affect clinical management? World J Surg Oncol. 2013; 11:49. PMID: 23445625.

10. Davey K, Heriot AG, Mackay J, et al. The impact of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography on the staging and management of primary rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008; 51:997–1003. PMID: 18461399.

11. Llamas-Elvira JM, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Gutiérrez-Sáinz J, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET in the preoperative staging of colorectal cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007; 34:859–867. PMID: 17195075.

12. Park IJ, Kim HC, Yu CS, et al. Efficacy of PET/CT in the accurate evaluation of primary colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006; 32:941–947. PMID: 16843635.

13. Ozkan E, Soydal C, Araz M, Kir KM, Ibis E. The role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting colorectal cancer recurrence in patients with elevated CEA levels. Nucl Med Commun. 2012; 33:395–402. PMID: 22367859.

14. Ruers TJ, Langenhoff BS, Neeleman N, et al. Value of positron emission tomography with [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose in patients with colorectal liver metastases: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2002; 20:388–395. PMID: 11786565.

15. Flamen P, Stroobants S, Van Cutsem E, et al. Additional value of whole-body positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in recurrent colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17:894–901. PMID: 10071281.

16. Ogunbiyi OA, Flanagan FL, Dehdashti F, et al. Detection of recurrent and metastatic colorectal cancer: comparison of positron emission tomography and computed tomography. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997; 4:613–620. PMID: 9416407.

17. Staib L, Schirrmeister H, Reske SN, Beger HG. Is (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in recurrent colorectal cancer a contribution to surgical decision making? Am J Surg. 2000; 180:1–5. PMID: 11036130.

18. Zervos EE, Badgwell BD, Burak WE Jr, Arnold MW, Martin EW. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as an adjunct to carcinoembryonic antigen in the management of patients with presumed recurrent colorectal cancer and nondiagnostic radiologic workup. Surgery. 2001; 130:636–643. PMID: 11602894.

19. Galandiuk S, Chaturvedi K, Topor B. Rectal cancer: a compartmental disease. The mesorectum and mesorectal lymph nodes. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2005; 165:21–29. PMID: 15865017.

20. Fong Y, Saldinger PF, Akhurst T, et al. Utility of 18F-FDG positron emission tomography scanning on selection of patients for resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. Am J Surg. 1999; 178:282–287. PMID: 10587184.

21. Rohren EM, Paulson EK, Hagge R, et al. The role of F-18 FDG positron emission tomography in preoperative assessment of the liver in patients being considered for curative resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2002; 27:550–555. PMID: 12169999.

22. Sahani DV, Kalva SP, Fischman AJ, et al. Detection of liver metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon and pancreas: comparison of mangafodipir trisodium-enhanced liver MRI and whole-body FDG PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005; 185:239–246. PMID: 15972430.

23. Furukawa H, Ikuma H, Seki A, et al. Positron emission tomography scanning is not superior to whole body multidetector helical computed tomography in the preoperative staging of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2006; 55:1007–1011. PMID: 16361308.

24. Valk PE, Abella-Columna E, Haseman MK, et al. Whole-body PET imaging with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in management of recurrent colorectal cancer. Arch Surg. 1999; 134:503–511. PMID: 10323422.

25. Kim SY, Lee SY, Kim HK, et al. Relationship between positron emission tomography uptake and macroscopic findings of colorectal cancer. Intest Res. 2012; 10:168–175.

26. Kijima S, Sasaki T, Nagata K, Utano K, Lefor AT, Sugimoto H. Preoperative evaluation of colorectal cancer using CT colonography, MRI, and PET/CT. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:16964–16975. PMID: 25493009.

27. Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010; 17:1471–1474. PMID: 20180029.

28. Lahaye MJ, Engelen SM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Imaging for predicting the risk factors--the circumferential resection margin and nodal disease--of local recurrence in rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005; 26:259–268. PMID: 16152740.

29. Imdahl A, Reinhardt MJ, Nitzsche EU, et al. Impact of 18F-FDG-positron emission tomography for decision making in colorectal cancer recurrences. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000; 385:129–134. PMID: 10796051.

30. Fernandez FG, Drebin JA, Linehan DC, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Strasberg SM. Five-year survival after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients screened by positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET). Ann Surg. 2004; 240:438–450. PMID: 15319715.

31. Flanagan FL, Dehdashti F, Ogunbiyi OA, Kodner IJ, Siegel BA. Utility of FDG-PET for investigating unexplained plasma CEA elevation in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1998; 227:319–323. PMID: 9527052.

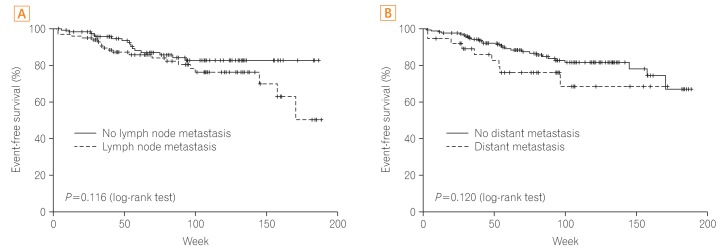

Fig. 2

Prognosis according to finding for lymph node and distant metastasis on CT scan. (A) Prognosis according to positive finding of lymph node metastasis. (B) Prognosis according to positive finding of distant metastasis.

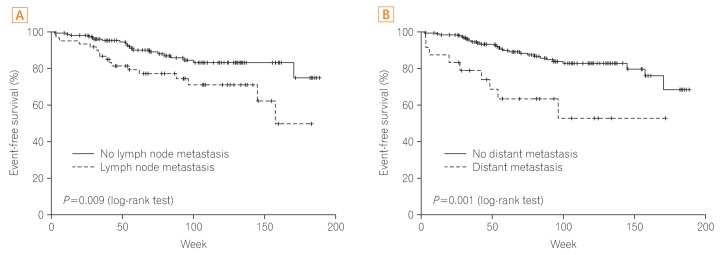

Fig. 3

Prognosis according to finding for lymph node and distant metastasis on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET/CT. (A) Prognosis according to positive finding of lymph node metastasis on FDG-PET/CT. (B) Prognosis according to positive finding of distant metastasis on FDG-PET/CT.

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

Table 2

Diagnostic Yield of CT and FDG-PET/CT for Lymph Node Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer

| CT (%) | FDG-PET/CT (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 62.3 | 66.8 | 0.022 |

| Sensitivity | 58.7 | 43.5 | 0.029 |

| Specificity | 64.8 | 83.6 | 0.000 |

| PPV | 54.5 | 65.6 | - |

| NPV | 68.6 | 67.3 | - |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download