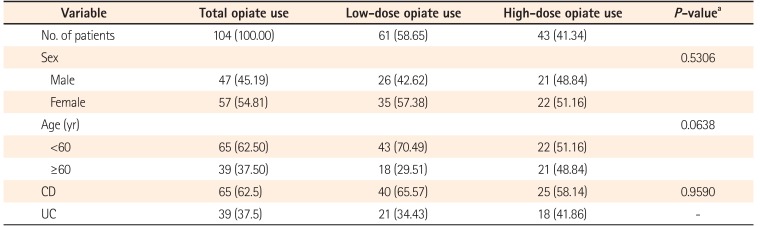

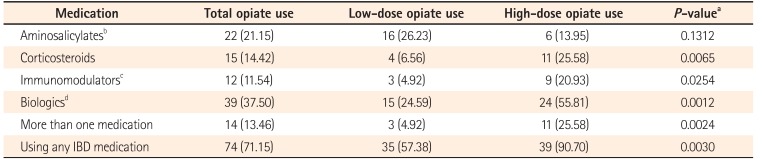

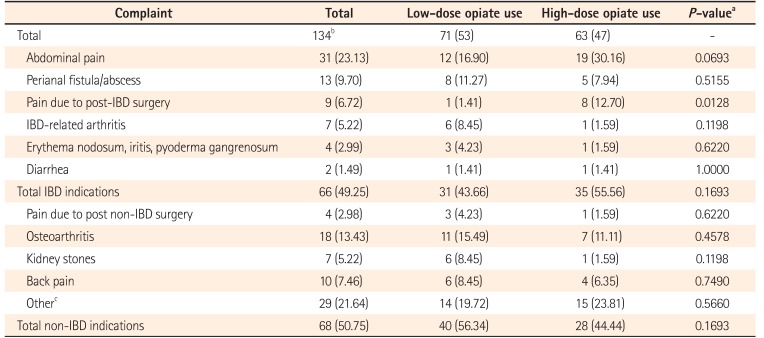

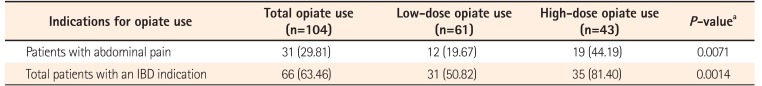

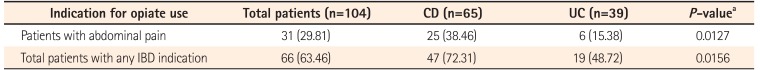

The analysis of our population-based cohort revealed the clinical indications for opiate use in patients with IBD. Opiate use for IBD has been associated with poor clinical outcomes. Although it was assumed that opiate use in the IBD population is related to IBD activity and its complications, our study is the first to directly establish this link. IBD-related complaints accounted for roughly half of the cited clinical indications for prescribing opiates in our IBD cohort as well as in the LD and HD opiate use subgroups. When analysis was conducted on a per-patient basis instead, it was found that almost two-thirds of the patients cited an IBD-related complaint as a reason for their opiate use, with this figure rising to 81% among the HD patients. The significantly higher use of IBD medications among HD users indirectly indicates that IBD activity or complaints could be the main factor influencing opiate use. Expectedly, abdominal pain was the most common indication for opiate use, particularly among CD patients, and was cited by almost half of the HD users. Perianal complaints were also commonly attributed to opiate use in the CD group. Notably, in contrast to traditional assumptions, diarrhea was rarely documented as an indication for opiate use by the prescribing physician or as relayed to the physician.

Other studies have examined the clinical features of IBD and opiate use, reporting important associations between IBD and co-morbid disease; however, they did not precisely define the indications for opiate use. Early work presented by Kaplan and Korelitz

12 from a single specialty IBD center noted a 30% risk of drug dependence among patients with IBD referred for psychiatric consultation. Edwards et al.,

13 utilizing an IBD database of 3 32 patients in Queensland Australia, studied patients with documented evidence of chronic opiate use over a period of 6 months for abdominal pain. After excluding patients with chronic active disease, diarrhea, and bowel obstruction, they identified 11 patients (10 with CD) who they defined as having “chronic narcotic misuse.” Two patients were excluded from the final analysis because of incomplete data. Of the remaining nine patients, six had diagnosed psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, anxiety with depression, bipolar illness, obsessive compulsive disorder, and personality disorder. Cross et al.

14 performed a retrospective review and case control analysis of 291 patients with CD followed over a 5-year period at the Medical College of Wisconsin's IBD Center. Similarly, patients who were prescribed opiates for diarrhea were excluded and those with active disease were included. The authors identified 38 patients (13.1%) who were opiate users, and its use was associated with psychiatric illness as determined from the increased neuropsychiatric drug use of 37% as compared to 19% among non-opiate users (

P=0.01). Opiate users had higher disease activity as measured by the Harvey Bradshaw Index (9.1 vs. 5.0,

P<0.001), lower quality of life scores as measured by the Short Form Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (44.2 vs. 51.6,

P=0.04), higher rates of disability (15.4% vs. 3.6%,

P=0.001), and longer disease duration (17.0 years vs. 12.9 years,

P=0.03). Logistic regression analysis also showed that smoking was more common among narcotic users (OR, 2.8). In another retrospective case control analysis of patients at the Mayo Clinic, Hanson et al.

15 identified 361 patients with IBD who were opiate users. Their final analysis of 100 mixed IBD cases (78 CD and 22 UC) was limited to patients receiving opiates for IBD indications, thereby excluding 194 patients who were receiving opiates for non-IBD indications and 67 patients without a confirmed IBD diagnosis. Unlike the findings in our study, the study by Hanson et al.

15 suggests that, in most cases, opiate use among IBD patients is unrelated to the disease itself, although it is not certain if multiple complaints cited by a subject were addressed or what comprised the IBD-related complaints in the 100 patients analyzed. Depression (42% vs. 19%,

P<0.001) and anxiety (19% vs. 7%,

P=0.02) were again found to be more common among opiate users, along with a history of abuse (17% vs. 3%,

P=0.006) and non-alcohol substance abuse (14% vs. 1%,

P<0.001). In their larger population-based study, Targownik et al.

9 also observed an association between depression (HR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.34–3.67) and substance abuse (HR, 4.05; 95% CI, 12.82–9.01) in HD opiate users, while acknowledging that their study design precluded the identification of precise indications for opiate use.

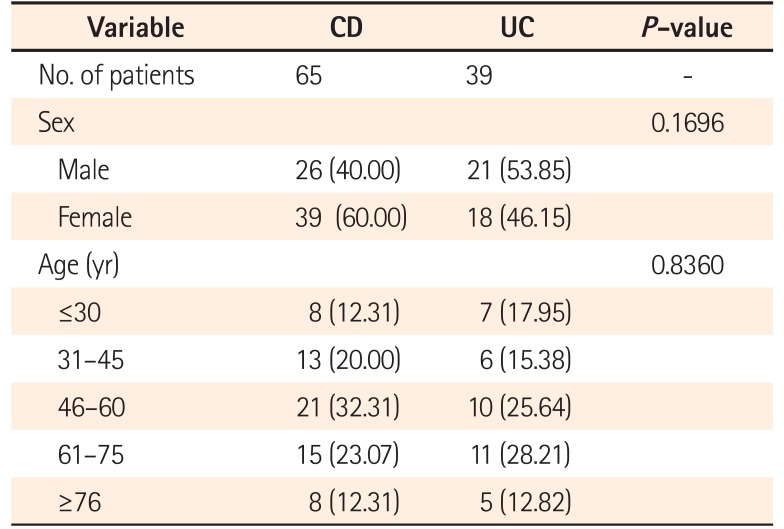

The main advantage of our study design was the use of population-based data available through the EMR system. After analyzing over 1.1 million subjects, we were able to identify 3,226 patients who had a diagnosis of IBD. While the IBD diagnosis was not validated by an additional review of the medical records, the observed prevalence of IBD of approximately 0.3% in our population was similar to the rate in the US population as a whole.

1617 We were able to define opiate use in 3.4% of our IBD patients, and this figure is slightly lower than that observed by Targownik. Unlike in the Manitoba Health database, patients included in the Northwell Health EMR system commonly consult physicians outside of the health care system, which blinds our investigation to opiate prescription that are not recorded within the system; this likely resulted in underreporting of opiate use in our cohort. Additionally, since only a single complaint or diagnosis needs to be linked to a prescription order in the EMR system, it is possible that the total number of clinical complaints was underreported. This linkage of prescription orders to a complaint or diagnosis may have also biased the results by enabling physicians to avoid linking an opiate prescription to a complaint that is perceived to be an unacceptable indication, e.g., diarrhea. Additionally, the date of the IBD diagnosis is not recorded in the EMR system, and therefore it is possible that some opiate prescriptions could have ordered prior to a formal IBD diagnosis. Another significant limitation of our study, which is common for retrospective investigations, was our inability to correlate complaints with disease activity, disease location, or behavior. While the absence of objectively defined disease activity would not automatically imply that a complaint was unrelated to IBD, it would have provided additional important insight into the nature of pain experienced by our patients, i.e., how much of what we see may be treatable by addressing IBD activity itself, and how much pain is beyond the scope of disease directed therapy. Since it is well known that there is often a disconnect between IBD complaints and true inflammatory disease activity,

181920 it is unlikely that increasing the scope or introducing new IBD-modifying therapies will suffice as alternatives for pain management.

Although opiate use in IBD has previously been associated with comorbidities such as smoking, substance abuse, and psychiatric diseases, the indications for use have been poorly defined. Our analysis of a non-referral center, population-based IBD cohort shows that IBD complaints, especially abdominal pain, are the most common indications for opiate use, particularly among HD users. While it is unknown if HD opiate use causes direct harm to patients, it should be assumed. Opiate use, irrespective of the reason, should be treated as a red flag, and physicians should thoroughly reevaluate cases to determine evidence of active disease and modify treatment accordingly. In cases where evidence of active disease is absent, early consultation with pain management specialists is recommended to help the patient limit or eliminate opiate use. Future research should address non-opiate pain management strategies for IBD-related pain along with an emphasis on early, highly effective IBD therapy to prevent the disease complications that would lead to opiate use.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download