Abstract

Background/Aims

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) primarily involves the intestinal tract and can affect vitamin absorption. This study was designed to assess the prevalence of vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies in patients with IBD, and to identify the risk factors associated with abnormal serum vitamin B12 and folate levels.

Methods

We evaluated the medical records of 195 patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and 62 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), and selected 118 healthy subjects for the control group.

Results

There were more CD patients with vitamin B12 deficiency than UC patients (14.9% vs. 3.2%, P=0.014) and controls (14.9% vs. 4.2%, P=0.003). The prevalence of folate deficiency was higher in CD patients than in controls (13.3% vs. 3.4%, P=0.004). There were no significant differences in the serum vitamin B12 and folate statuses of the UC and control groups. Patients with prior ileal or ileocolic resection showed a higher prevalence of abnormal vitamin B12 levels than those without prior resection (n=6/16, n=23/179; P=0.018). A disease duration within 5 years was a risk factor of abnormal folate levels in CD patients.

Conclusions

This study showed that vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies were more common in patients with CD than in UC patients and controls. Prior ileal or ileocolonic resection was a risk factor of serum vitamin B12 abnormalities, and a disease duration within 5 years was a risk factor of low serum folate levels in CD patients.

As water-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12 and folate are essential to erythropoiesis and to the nervous system function, while a lack of these vitamins can cause corresponding diseases. Common causes of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency include an insufficient intake, malabsorption, or an increased demand. Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, cannot be synthesized by the human body and must therefore be absorbed orally. Dietary cobalamin is separated from its binding protein by hydrochloric acid and pepsin in the stomach, before combining with the intrinsic factor (IF) in the duodenum. The complex is then absorbed through the mucosa in the terminal ileum.1 By contrast, folate is present in both animal and plant foods, and is absorbed in the proximal small intestine, including in the duodenum and the jejunum.2

IBD is a chronic, repeated-relapsing disease of the intestinal tract that includes CD and UC. CD frequently involves the terminal ileum. As long-term inflammation of the mucosa and surgical resection for stricture or fibrosis can affect the vitamin B12 absorption, patients with CD tend to suffer from vitamin B12 deficiency.3 Some studies have suggested that vitamin B12 deficiency was more common in patients with CD than in those with UC.345 Conversely, UC is an inflammatory disease that primarily involves the colon, without involvement of the small intestine. It seems that the prevalence of vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies are similar in UC patients and in healthy individuals.

In order to manage the vitamin status of IBD patients well, this study was designed to assess the prevalence of vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies in patients with IBD and to identify the risk factors associated with abnormal serum vitamin B12 and folate levels.

A total of 257 patients who presented with IBD (195 CD and 62 UC) between December 2011 and August 2015 were included in this study. The research subjects were inpatients of the Renji Hospital of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine who had been diagnosed with IBD based on clinical, endoscopic, laboratory, histologic, and radiographic information. The electronic medical records of the patients were analyzed to determine their demographic profiles, disease duration, disease location, CD behavior (based on the Montreal classification), drug therapy, and laboratory parameters. Patients with known diseases other than IBD that could cause abnormal vitamin B12 and folate concentrations or who were receiving supplemental vitamins were excluded. In addition, four patients were excluded from the statistical analysis as their serum vitamin values were above the upper limit of the measured values (one vitamin B12 value >1,500 pg/mL, three folate values >25.2 ng/mL). As a control group, 118 subjects were selected among, healthy individuals who visited the hospital for a health check-up.

An automated chemiluminescence system (Beckman Access method; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) was used to determine the vitamin concentrations in the serum. Vitamin B12 deficiency was defined as a serum level below 200 pg/mL and folate deficiency was defined as a serum level below 3 ng/mL. Anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level <120 g/L in men and <110 g/L in women, and macrocytosis was defined as a mean cell volume >99 fL, based on local laboratory values. The CRP was recorded as a marker of inflammation.

All the statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The continuous variables were presented as means and SDs or medians and interquartile ranges. The statistical analysis was performed with a t-test. When the variables of the vitamin B12 and folate were not normally distributed between the groups, Mann-Whitney U tests were used. Chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests were performed to compare the prevalences of the vitamin deficiencies. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant, and 95% CI were calculated for the mean and proportion.

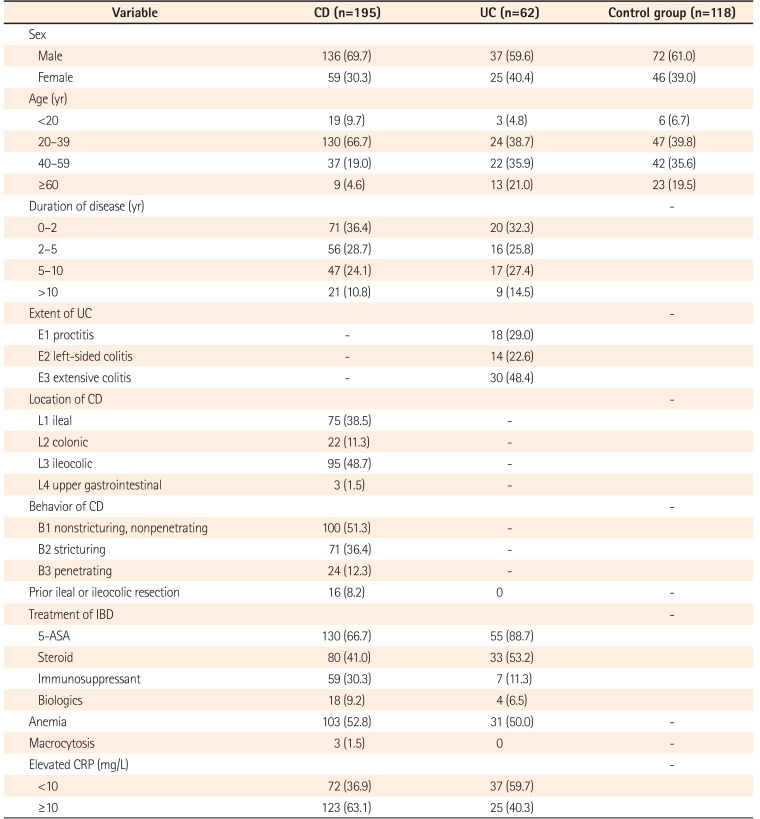

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients with CD and UC are presented in Table 1. The CD patients' profiles were similar to those of the UC patients and controls in terms of sex, and the CD patients' disease duration was similar to that of the UC patients (P>0.05). The age was similar between the UC and control groups (P>0.05). There were more subjects aged 20 to 39 years in the CD group than in the UC and control groups. The prevalence of anemia was 52.8% (95% CI, 46.2%–60%) in the CD patients, and 50% (95% CI, 37.1%–62.9%) in the UC patients. Macrocytosis was observed in 1.5% (95% CI, 0–3.6%) of the CD patients, and in none of the UC patients.

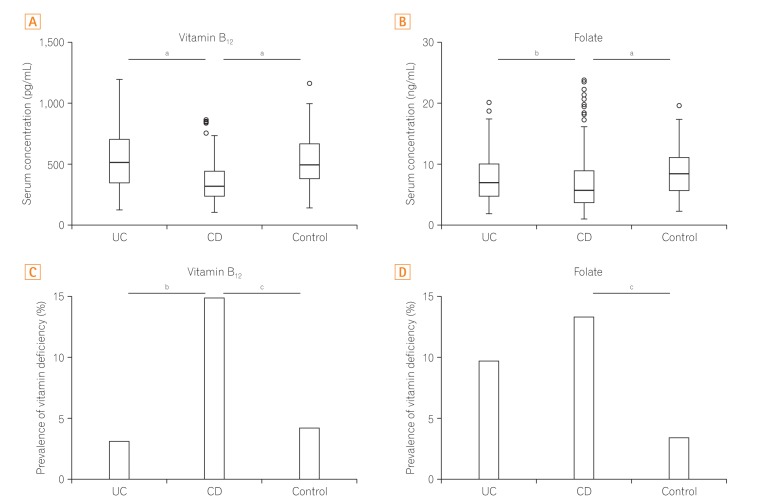

In CD patients, the mean serum vitamin B12 and folate concentrations were 359.53±170.08 pg/mL and 7.11±4.75 ng/mL, respectively (Fig. 1). These two values were significantly lower than in the UC patients and controls (P<0.05). There was a greater prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in CD patients than in UC patients (14.9% vs. 3.2%, P=0.014) and controls (14.9% vs. 4.2%, P=0.003). The prevalence of folate deficiency was also higher in CD patients than in controls (13.3% vs. 3.4%, P=0.004). However, there was no significant difference between the CD and UC groups (13.3% vs. 9.7%, P=0.448). As shown in Fig. 1, there were no significant differences between the serum vitamin B12 and folate statuses of the UC and control patients.

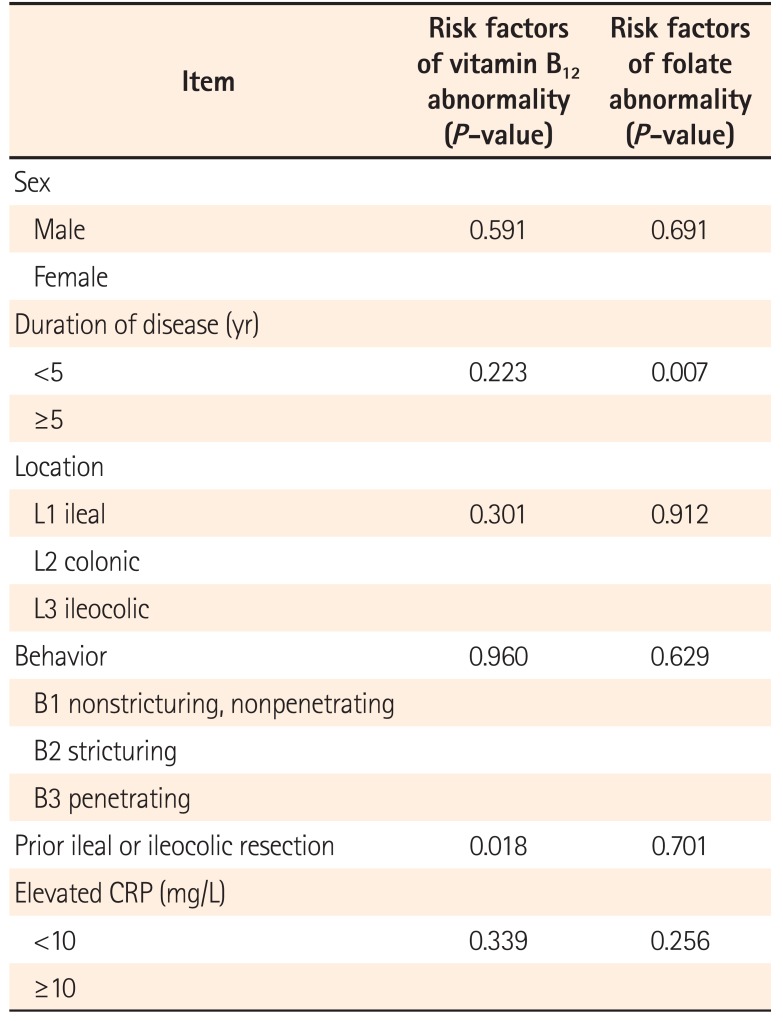

The results of the further univariate analysis are presented in Table 2. Regarding CD patients, those with prior ileal or ileocolic resection showed a higher prevalence of abnormal vitamin B12 levels than those without prior resection (n=6/16, n=23/179; P=0.018). Interestingly, patients with prior ileal or ileocolic resection revealed higher serum folate concentrations than those without prior small intestinal resection (10.40±6.16 ng/mL vs. 6.82±4.50 ng/mL, P=0.004), although without significant differences in the prevalence of abnormal folate levels (n=1/16, n=25/179; P=0.701). In CD patients, a disease duration within 5 years was a risk factor of abnormal folate levels (n=23/127, n=3/68; P=0.007).

Vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies are important health problems that may not only cause hematologic, neural, gastrointestinal, and mental abnormalities, but are also associated with an increased risk of diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, cognitive dysfunction, and dementia.67 Folate deficiency is also known as an established risk factor of colorectal cancer in IBD patients.8 These situations increase the need for hospital admissions and decrease the quality of life of IBD patients. However, as the symptoms of IBD patients with vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies are not very typical and can be masked by other pathogenic factors, they are sometimes overlooked in the management of IBD patients. In our study, for instance, not all CD patients with vitamin B12 or folate deficiency showed macrocytosis. This can be partly explained by the fact that in IBD patients, vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies overlap with iron metabolism abnormalities, and the latter can mask a morphological type of anemia.9 Therefore, there is a need to expand the knowledge of vitamin deficiency in IBD patients.

This study showed that vitamin B12 deficiency was more common in CD patients than in UC patients and controls. While a number of previous studies indicated that CD patients tended to present vitamin B12 deficiencies, others did not support this finding.101112 The reported prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with CD ranged from 5.6% to 38%.13 Vitamin B12 deficiency in IBD patients has multiple potential mechanisms, including inflammation of the distal ileum, the development of fistulas, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and resection of the distal ileum.5 There have also been conflicting findings about the average serum vitamin B12 levels of patients with CD. While several studies have reported low average vitamin B12 levels in CD patients, others have found contradicting results.35101112131415 In our study, the patients with CD had significantly lower levels of serum vitamin B12 than the UC patients and controls, while the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency was similar in the UC patients and controls. These results echoed those of previously reported studies about the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with UC.35

Although ileum CD mainly affects the terminal ileum, which is where vitamin B12 is absorbed, previous studies have not considered the disease as a risk factor of abnormal vitamin B12 levels.345 A recent study used holotranscobalamin and methylmalonic acid to identify an impaired cobalamin status, and revealed that ileal inflammation was an independent risk factor of B12 deficiency.16 Although prior ileal or ileocolonic resection is a known risk factor of B12 deficiency,412 the risk depends on the resection length, as the latter affects the availability of the cobalamin-IF receptors for vitamin B12 absorption, and thereby the prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency.17 Interestingly, in our study, patients with prior ileal or ileocolonic resection showed a high prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency and a high serum folate concentration. Evidence has suggested that high serum folate concentrations could mask anemia and exacerbate potential adverse events such as neurological symptoms in patients with low vitamin B12.6 This situation should raise concerns, and calls for closer monitoring of patients with ileal or ileocolonic resection.

Folate deficiency seemed to be associated with IBD. CD patients have been reported to have a significantly higher prevalence of folate deficiency than healthy control patients and UC patients.34 In our study, the prevalence of folate deficiency in patients with CD was also higher than in control patients, and there was no significant difference between its prevalence in UC patients and in controls. However, the mechanism of folate deficiency in IBD remains unclear. As folate is absorbed in the duodenum and the proximal jejunum, IBD that mainly involves the ileum and the colon will not cause folate deficiency. The latter may be brought on by a poor diet, malabsorption, and increased requirements when the disease is active.18 Our study revealed that a disease duration within 5 years was a risk factor of abnormal folate levels in CD patients. A previous study showed that folate and cobalamin levels were significantly lower in patients with active IBD than in those with inactive IBD.11 Folate deficiency may be caused by therapeutic agents such as sulfasalazine and methotrexate.1920

Table 1 shows that IBD patients received a therapeutic regimen of high 5-aminosalicylic acid or immunosuppressants doses. This may explain our result.

There were several limitations to our study. First, its retrospective nature involved inherent drawbacks, including a potential selection bias. Second, the numbers of certain subgroups in the univariate analysis were too low, which increased the risks of statistical errors in the statistical analyses. Therefore, future studies using larger samples are needed to evaluate the risk factors of vitamin deficiencies in IBD patients.

In conclusion, this study found that vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies were more common in patients with CD than in UC patients and controls. Prior ileal or ileocolonic resection was a risk factor of serum vitamin B12 abnormalities, and a disease duration within 5 years was a risk of low serum folate levels in CD patients.

Notes

References

1. O'Leary F, Samman S. Vitamin B12 in health and disease. Nutrients. 2010; 2:299–316. PMID: 22254022.

2. Krishnaswamy K, Madhavan Nair K. Importance of folate in human nutrition. Br J Nutr. 2001; 85(Suppl 2):S115–S124. PMID: 11509099.

3. Yakut M, Ustün Y, Kabaçam G, Soykan I. Serum vitamin B12 and folate status in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Intern Med. 2010; 21:320–323. PMID: 20603044.

4. Bermejo F, Algaba A, Guerra I, et al. Should we monitor vitamin B12 and folate levels in Crohn's disease patients? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013; 48:1272–1277. PMID: 24063425.

5. Headstrom PD, Rulyak SJ, Lee SD. Prevalence of and risk factors for vitamin B(12) deficiency in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008; 14:217–223. PMID: 17886286.

6. Hughes CF, Ward M, Hoey L, McNulty H. Vitamin B12 and ageing: current issues and interaction with folate. Ann Clin Biochem. 2013; 50(Pt 4):315–329. PMID: 23592803.

7. Nazki FH, Sameer AS, Ganaie BA. Folate: metabolism, genes, polymorphisms and the associated diseases. Gene. 2014; 533:11–20. PMID: 24091066.

8. Pohl C, Hombach A, Kruis W. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease and cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000; 47:57–70. PMID: 10690586.

9. Weiss G, Gasche C. Pathogenesis and treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Haematologica. 2010; 95:175–178. PMID: 20139387.

10. Vagianos K, Bernstein CN. Homocysteinemia and B vitamin status among adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a one-year prospective follow-up study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012; 18:718–724. PMID: 21604334.

11. Erzin Y, Uzun H, Celik AF, Aydin S, Dirican A, Uzunismail H. Hyperhomocysteinemia in inflammatory bowel disease patients without past intestinal resections: correlations with cobalamin, pyridoxine, folate concentrations, acute phase reactants, disease activity, and prior thromboembolic complications. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008; 42:481–486. PMID: 18344891.

12. Jayaprakash A, Creed T, Stewart L, et al. Should we monitor vitamin B12 levels in patients who have had end-ileostomy for inflammatory bowel disease? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004; 19:316–318. PMID: 14618349.

13. Battat R, Kopylov U, Szilagyi A, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence, risk factors, evaluation, and management. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014; 20:1120–1128. PMID: 24739632.

14. Lambert D, Benhayoun S, Adjalla C, et al. Crohn's disease and vitamin B12 metabolism. Dig Dis Sci. 1996; 41:1417–1422. PMID: 8689919.

15. Kallel L, Feki M, Sekri W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of hyperhomocysteinemia in Tunisian patients with Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011; 5:110–114. PMID: 21453879.

16. Ward MG, Kariyawasam VC, Mogan SB, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for functional vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015; 21:2839–2847. PMID: 26296064.

17. Behrend C, Jeppesen PB, Mortensen PB. Vitamin B12 absorption after ileorectal anastomosis for Crohn's disease: effect of ileal resection and time span after surgery. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995; 7:397–400. PMID: 7614100.

18. Hoffbrand AV, Stewart JS, Booth CC, Mollin DL. Folate deficiency in Crohn's disease: incidence, pathogenesis, and treatment. Br Med J. 1968; 2:71–75. PMID: 5646094.

19. Hwang C, Ross V, Mahadevan U. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease: from A to zinc. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012; 18:1961–1981. PMID: 22488830.

20. Mullin GE. Micronutrients and inflammatory bowel disease. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012; 27:136–137. PMID: 22223669.

Fig. 1

Serum vitamin B12 and folate status in IBD patients and controls. (A) The mean serum vitamin B12 concentrations of CD patients was 359.53±170.08 pg/mL, This was significantly lower than in UC patients and controls. (B) The mean serum folate concentrations of CD patients was 7.11±4.75 ng/mL, This was significantly lower than in UC patients and controls. (C) The prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency was significantly higher in CD patients than in UC patients (14.9% vs. 3.2%, P=0.014) and controls (14.9% vs. 4.2%, P=0.003). (D) The prevalence of folate deficiency was higher in CD patients than in controls (13.3% vs. 3.4%, P=0.004). there was no significant difference between the CD and UC groups (13.3% vs. 9.7%, P=0.448). aP<0.05; bP<0.01; cP<0.001.

Table 1

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with IBD

Table 2

Risk Factors of Vitamin Abnormality in CD Based on Univariate Analysis

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download