Abstract

Purpose

The use of absorbable skin staplers (ASS) for skin closure has been increasing due to their convenience and time-saving effect. In this study, we evaluated the effectiveness of ASS in reducing skin closure time and its safety regarding surgical site infection (SSI), comparing it to conventional hand sewing (HS) in patients who underwent mastectomy.

Methods

A single-center, retrospective study was conducted. The electronic medical records of patients who underwent mastectomy between July 2015 and June 2020 in Samsung Medical Center were reviewed. The data included previously known risk factors for SSI. We compared the time expended on skin closure and the occurrence rate of SSI between the ASS group and the HS group.

Results

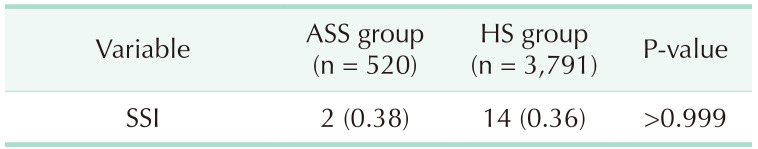

We included 4,311 patients in the analysis. Among them, 520 patients were treated with ASS and 3,791 patients with HS. The average time for skin closure was 16.2 ± 10.1 minutes in the ASS group and 36.5 ± 29.0 minutes in the HS group (P < 0.001). The SSI rate was 0.38% (2 of 520) in the ASS group and 0.36% (14 of 3,791) in the HS group (P > 0.999).

Go to :

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has classified surgical wounds into 4 categories according to the degree of contamination of the wound at the time of operation [1]. For class I, which means clean wound including breast surgery, the expected surgical site infection (SSI) rate is less than 2% [2]. Whether SSI occurs or not can be one of the most critical components for success of the operation, especially in clean surgeries.

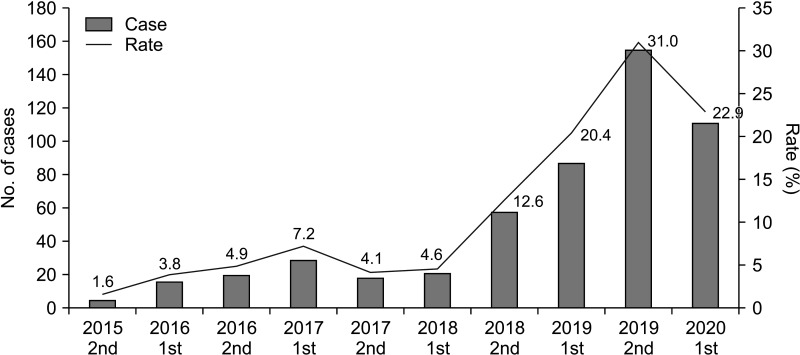

Meanwhile, there is the alternative of conventional hand-sewing (HS) sutures for skin closure, which is commonly used these days. Absorbable skin stapler (ASS) is a closure device designed to create symmetric dermis-to-dermis closures. The staple is composed of a copolymer derived from polylactide-polyclycolide and absorbed over 90–120 days after being applied in the subcuticular layer [3]. ASS is now widely used in various surgical fields such as plastic surgery, obstetrics, orthopedics, and so on. According to previous studies, ASS showed excellent results in improving postoperative pain, scar, and cost [45678]. Most of all, it can reduce the time for skin closure thereby reducing unnecessary anesthetic time for patients, as well as providing convenience for surgeons. In the same manner, the use of ASS in breast cancer surgery has also been increasing. Fig. 1 shows the number and rate of cases in which ASS was used for skin closure among mastectomies for the last 5 years in our center.

Considering this trend of increasing use of ASS, we designed this study to prove the efficacy and safety of ASS. The target of our study was to review the effectiveness of ASS in reducing the time for skin closure and the safety of ASS in regard to SSI in mastectomy.

Go to :

The protocol of this project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (No. 2021-03-066). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was provided by all participants.

A single-center, retrospective study was conducted. The electronic medical records of patients who underwent mastectomy between July 2015 and June 2020 in Samsung Medical Center were reviewed. Considering the length of the wound, reducing the skin closure time is more of a concern in mastectomy than in breast-conserving surgery. Therefore, most of the cases in which ASS was used for skin closure were mastectomies, and patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery were not included in this study. Also, patients who underwent breast reconstruction immediately following mastectomy were not included.

The data of previously known risk factors for SSI including age, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, alcohol drinking, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (PS) classification, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and previous radiotherapy was collected. The primary outcomes were time for skin closure and SSI rate. Every operation room in our center records the time of initiation and end of anesthetic induction, the time of skin incision, initiation of skin closure, and end of the total operation. We checked the time of initiation of skin closure and the time of end of the operation in every case and calculated the time expended on skin closure. Monitoring and data collection for SSI is conducted by the Center for Infection Prevention and Control (CIC) of Samsung Medical Center, which conforms to the standardized criteria by CDC guidelines. According to the CDC guidelines, SSI is defined as an infection that occurs within 30 days after operative procedure if no implant is left, and the patient should have one of the following; (a) purulent drainage from the incision; (b) organisms isolated from the culture of fluid or tissue from the incision; (c) inflammatory symptoms or signs such as pain, tenderness, swelling, redness, and fever; (d) an abscess or other evidence of infection; or e) diagnosis by the surgeon or attending physician [9]. We also used the same definition of SSI and, therefore, monitoring and following up for SSI was confined to 30 days after the operation. All the surgeons or physicians in our center are supposed to report the SSI to the CIC of our center through an electronic medical record system whenever they detect it, and the CIC also regularly monitors the results of cultures.

Based on these data, we compared the time expended on skin closure and the occurrence rate of SSI between the ASS group and the HS group. Also, we compared the above risk factors between the patients with SSI and without SSI among the ASS group to identify significant risk factors for SSI when using ASS, and to validate appropriate indication/contraindication for ASS.

There was no difference in surgical procedure between the ASS group and HS group except for skin closure. For the ASS group, we used Insorb (Incisive Surgical, Inc.), which is a brand name of absorbable subcuticular skin stapler. First, the operator grasps both edges of the skin together with a tooth forceps using 1 hand, while the other hand holds the stapler. After locating the nose of the stapler underneath the grasped tissue, the operator fires the staple. This process is repeated along the incision till the opposite end, and staples are placed at about 7-mm intervals. Fig. 2 shows a mastectomy field from our center in which an ASS was being applied. For the HS group, interrupted subcuticular suture was done using Monosyn (B. Braun). First-generation cephalosporin was injected once on the day of the operation as a prophylactic antibiotic into every patient, and no additional antibiotics were used postoperatively. Only for the patients in whom SSI was detected was an additional third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole used empirically; or in cases of positive culture from the wound, other proper antibiotics were administered according to the result of the culture.

For comparison of the risk factors of SSI between the 2 groups, we used the t-test for continuous variables, Mann-Whitney U-test for ordinal variables, and the chi-square test and Fisher exact test for nominal variables. The skin closure time and SSI rate were compared using the t-test. The P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 27.0 (IBM Corp.) was used for the statistical analysis.

Go to :

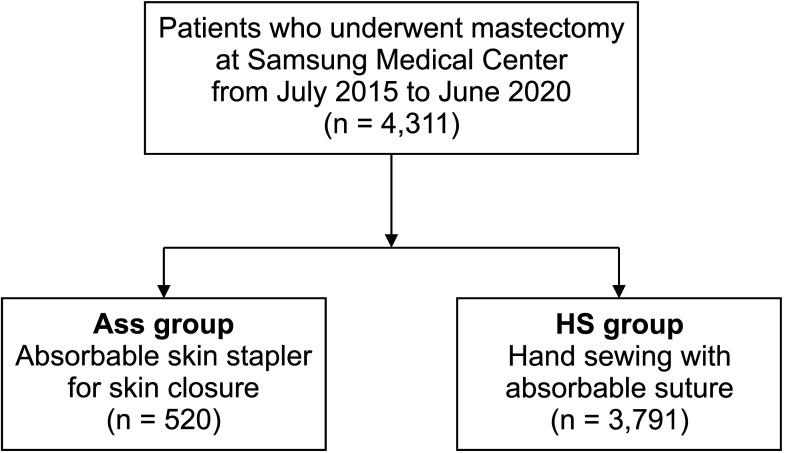

A total of 4,311 patients underwent mastectomy without immediate reconstruction between July 2015 and June 2020 in Samsung Medical Center. ASS was used for skin closure in 520 cases and HS suture was done in the remaining 3,791 cases. Fig. 3 is a diagram of the study population.

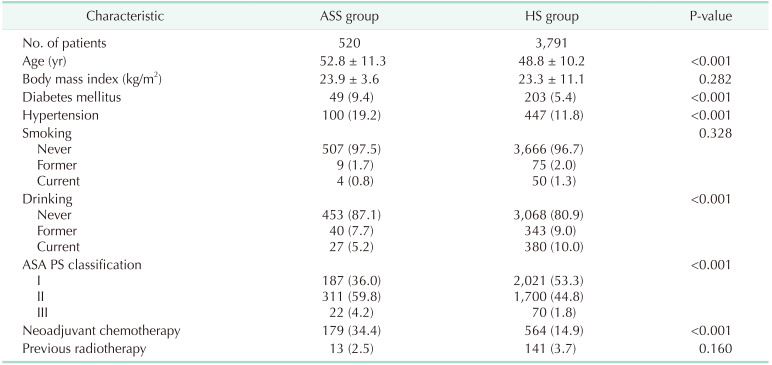

Table 1 shows the demographics of the 2 groups. Nine previously known risk factors for SSI are included in the table. There was no significant difference in BMI, smoking history, and previous radiotherapy between the 2 groups, but the ASS group showed inferiority to the HS group for the remaining risk factors. That is, the patients in the ASS group were older, had diabetes and hypertension at a higher rate, had higher ASA PS grade, and had a higher rate of history of neoadjuvant chemotherapy than those in the HS group significantly. Only regarding the factor of alcohol drinking was the rate of patients who were ex-drinker or current drinker higher in the HS group than in the ASS group, respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

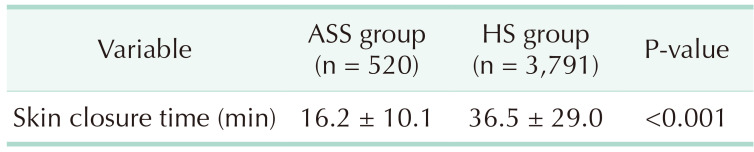

Table 2 shows the comparison of the skin closure time between the 2 groups. The average time for skin closure was 16.2 ± 10.1 minutes in the ASS group and 36.5 ± 29.0 minutes in the HS group, which was significantly shorter in the ASS group (P < 0.001). Table 3 shows the SSI rate of the 2 groups. The SSI rate was 0.38% (2 of 520) in the ASS group and 0.36% (14 of 3,791) in the HS group, which was not significantly different (P > 0.999).

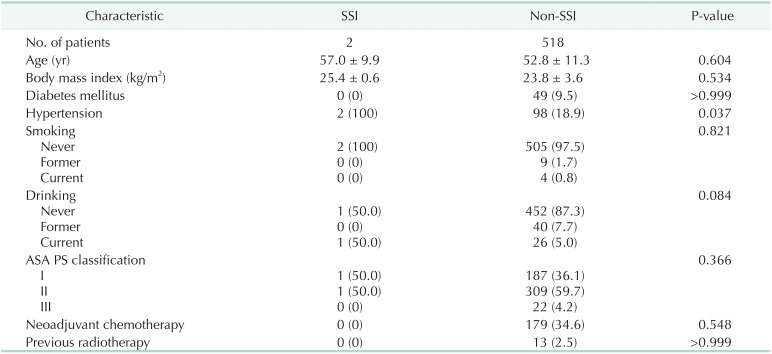

In addition, we compared the risk factors for SSI between the patients with SSI and without SSI among the ASS group. However, there were only 2 patients who suffered from SSI in the ASS group. Table 4 shows the results.

Go to :

Insorb, which is an absorbable subcuticular skin stapler used in this study, was first launched in January 2005, and since then there have been many studies proving the efficacy of ASS in terms of pain, cosmetic outcome, and cost in various surgical fields [310111213]. In the same manner, this study was purposed to identify the application of ASS in breast cancer surgery regarding efficacy and safety, especially for SSI because the control of SSI can be a more sensitive and critical matter in clean surgery. Our study showed that ASS decreased the time for skin closure significantly but did not increase the SSI.

This study was performed retrospectively by reviewing the electronic medical records of the patients. As a result, there was a great bias between the ASS group and the HS group. In more than half of the variables, the ASS group showed more vulnerable characteristics to SSI than the HS group. Additional review of medical records was done and we found that in the cases in which the general condition of the patient was poor, associated with the patients’ underlying disease or history of neoadjuvant therapy, the anesthesiologists required the surgeons to explain and warn of the risk of morbidities from general anesthesia to the patient and their families with extra-concern, and sometimes recommended intensive care unit care postoperatively. Systemic complications associated with general anesthesia can progress as the anesthetic time increases [141516]. In such cases, surgeons would have made an effort to reduce the time of operation and might have tended to use ASS rather than HS for skin closure. It is thought that these circumstances played a role in making the result of such uneven demographics of the 2 groups. Despite all, the ASS group did not show a higher incidence of SSI.

Long duration of operation can be related not only to systemic morbidities from general anesthesia but also to various surgical complications such as SSI, wound dehiscence, and following reoperation [1718192021]. These complications prolong the length of hospital stay and, as a result, increase the financial cost to patients. Therefore, the time-saving effect of ASS can have potentially more broad benefits in terms of morbidity, patients’ quality of life, and cost-effectiveness.

At the stage of study design, we were intent on comparing the risk factors between patients with SSI and without SSI among the ASS group in order to identify significant risk factors for SSI when using ASS and validate appropriate indication/contraindication for ASS. However, there were only 2 patients who suffered from SSI in the ASS group, and it could not be reasonable to draw a statistically meaningful conclusion by comparing those 2 patients with the rest of the 518 patients in the ASS group. However, from a different point of view, this can empower the conclusion that the use of ASS does not affect the occurrence of SSI significantly.

On the other hand, there is a disadvantage to using ASS. Because of the nature that the staple is placed in the subcuticular layer, there is an issue that the most superficial part of the skin can diverge. To overcome this problem, surgeons in our center attempted various techniques and, nowadays, we use ASS in combination with conventional metal staplers. First, we close the skin using an absorbable subcuticular skin stapler and then apply metal staples at both tip portions of the wound where the edge can easily dislocate. Next, we apply additional metal staples selectively at the points where the wound is expected to diverge or the tension is strong. The metal staples are applied to the very superficial part of the skin slightly, not firmly deep into the skin, so that they can help us connect the surfaces of both sides of the wound, but not irritate the skin around. By using ASS with this method, we could prevent the edge of the wound from diverging or being dislocated without leaving severe scars. Fig. 4 is an example of a completed mastectomy field at our center in which an ASS was applied in combination with the metal staples.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was a single institution, retrospective study. Second, there was a bias due to the differing tendencies of the ASS group and the HS group, although the ASS group showed good results despite that bias. Third, the data on complications other than SSI, such as wound dehiscence or disruption, was not collected. Fourth, there was no comparison of cosmetic results or patient satisfaction. If further data is collected using scoring sheets for cosmetic results or questionnaires for patient satisfaction, it would be much more helpful to validate the effectiveness of ASS. Comparing the photos of the surgical wounds from the ASS group and the HS group to assess the change over time would be a good method also. Finally, we assumed that ASS would be able to help reduce patient morbidity, hospital stay, and cost by shortening the operation time reflecting the results of previous studies; the actual data was not collected nor compared in this study. Additional data collection and analysis are necessary for this point.

To sum up, the use of ASS in mastectomy reduced the time for skin closure significantly but did not increase the SSI. Therefore, it can be an effective and safe choice to use ASS instead of HS for skin closure in mastectomy. No significant risk factor for SSI when using ASS was identified in this study.

Go to :

References

1. KHerman TF, Bordoni B. Wound Classification. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing;2022. updated 2022 Apr 28. cited 2021 Sep 28. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554456/

.

2. Kugler NW, Carver TW, Paul JS. Negative pressure therapy is effective in abdominal incision closure. J Surg Res. 2016; 203:491–494. PMID: 27363660.

3. CooperSurgical, Inc. The INSORB skin stapler [Internet]. CooperSurgical, Inc.;c2023. cited 2021 May 12. Available from: https://www.insorb.com/insorb-overview/

.

4. Patel V, Green JL, Christopher AN, Morris MP, Weiss ES, Broach RB, et al. Use of absorbable dermal stapler in reduction mammoplasty: assessing technical, quality-of-life, and aesthetics outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021; 9:e3784. PMID: 34476162.

5. Nitsche J, Howell C, Howell T. Skin closure with subcuticular absorbable staples after cesarean section is associated with decreased analgesic use. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012; 285:979–983. PMID: 22037686.

6. Fisher DA, Bengero LL, Clapp BC, Burgess M. A randomized, prospective study of total hip wound closure with resorbable subcuticular staples. Orthopedics. 2010; 33:665. PMID: 20839703.

7. Malard O, Duteille F, Darnis E, Espitalier F, Perrot P, Ferron C, et al. A novel absorbable stapler provides patient-reported outcomes and cost-effectiveness noninferior to subcuticular skin closure: a prospective, single-blind, randomized clinical trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020; 146:777e–789e.

8. Schrufer-Poland TL, Ruiz MP, Kassar S, Tomassian C, Algren SD, Yeast JD. Incidence of wound complications in cesarean deliveries following closure with absorbable subcuticular staples versus conventional skin closure techniques. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016; 206:53–56. PMID: 27632411.

9. Huotari K. Surveillance of surgical site infections following major hip and knee surgery in Finland. Finland National Public Health Institute;2007.

10. Edlich RF, Gubler K, Stevens HS, Wallis AG, Clark JJ, Dahlstrom JJ, et al. Scientific basis for the selection of surgical staples and tissue adhesives for closure of skin wounds. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2010; 29:327–337. PMID: 21284596.

11. Duteille F, Rouif M, Alfandari B, Andreoletti JB, Sinna R, Laurent B, et al. Reduction of skin closure time without loss of healing quality: a multicenter prospective study in 100 patients comparing the use of Insorb absorbable staples with absorbable thread for dermal suture. Surg Innov. 2013; 20:70–73. PMID: 22589018.

12. Bron T, Zakine G. Placement of absorbable dermal staples in mammaplasty and abdominoplasty: a 12-month prospective study of 60 patients. Aesthet Surg J. 2016; 36:459–468. PMID: 26530478.

13. Cross KJ, Teo EH, Wong SL, Lambe JS, Rohde CH, Grant RT, et al. The absorbable dermal staple device: a faster, more cost-effective method for incisional closure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 124:156–162. PMID: 19568054.

14. Gu A, Wei C, Chen AZ, Malahias MA, Fassihi SC, Ast MP, et al. Operative time greater than 120 minutes is associated with increased pulmonary and thromboembolic complications following revision total hip arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2020; 30:1393–1400. PMID: 32524203.

15. Scott CF Jr. Length of operation and morbidity: is there a relationships? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982; 69:1017–1021. PMID: 7079394.

16. Harris M, Chung F. Complications of general anesthesia. Clin Plast Surg. 2013; 40:503–513. PMID: 24093647.

17. Singh S, Swarer K, Resnick K. Longer operative time is associated with increased post-operative complications in patients undergoing minimally-invasive surgery for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017; 147:554–557. PMID: 28982521.

18. Cregar WM, Goodloe JB, Lu Y, Gerlinger TL. Increased operative time impacts rates of short-term complications after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2021; 36:488–494. PMID: 32921548.

19. Allan J, Goltsman D, Moradi P, Ascherman JA. The effect of operative time on complication profile and length of hospital stay in autologous and implant-based breast reconstruction patients: an analysis of the 2007-2012 ACS-NSQIP database. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020; 73:1292–1298. PMID: 32201323.

20. Brady JS, Desai SV, Crippen MM, Eloy JA, Gubenko Y, Baredes S, et al. Association of anesthesia duration with complications after microvascular reconstruction of the head and neck. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018; 20:188–195. PMID: 28983575.

21. Surace P, Sultan AA, George J, Samuel LT, Khlopas A, Molloy RM, et al. The association between operative time and short-term complications in total hip arthroplasty: an analysis of 89,802 surgeries. J Arthroplasty. 2019; 34:426–432. PMID: 30528133.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download