Abstract

Purpose

Rectal prolapse is a benign disease in which the rectum protrudes below the anus. Although many studies have been reported on the treatment of primary rectal prolapse for many years, there is a lack of treatment or clinical research results on recurrent rectal prolapse. This study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of surgical approaches for recurrent rectal prolapse.

Methods

We studied patients who underwent surgical treatment for recurrent rectal prolapse disease from March 2016 to February 2021. We analyzed the previous operation methods in patients with recurrent rectal prolapse, as well as the operation time, complication rate, hospital stay, and re-recurrence rates in the perineal and abdominal approach groups.

Results

Out of a total of 239 patients, 41 patients who underwent surgery for recurrent rectal prolapse were retrospectively enrolled. Recurrent rectal prolapses were surgically treated either by the perineal approach (n = 25, 61.0%) or by the abdominal approach (n = 16, 39.0%). The operation times were significantly longer in the abdominal approach than in the perineal approach (98.44 minutes vs. 58.00 minutes, P = 0.001). Hospital stay was significantly longer in the abdominal approach than in the perineal approach (9.19 days vs. 6.00 days, P = 0.012). Re-recurrence rate after repeat repair was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P = 0.777).

Rectal prolapse is a benign disease caused by the rectal wall overlapping or protruding completely outside the anal canal. Rectal prolapse is generally more common in women than in men [1]. As the world enters an aging society, the prevalence and severity of rectal prolapse are also increasing [2]. It is shown that the degree of rectal prolapse becomes more severe with increasing age [3]. Rectal prolapse is usually accompanied by symptoms such as anal pain, bleeding, constipation, and fecal incontinence [4]. Rectal prolapse is not a life-threatening disease, but it is a disease that requires accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment because it is a painful condition that can seriously affect the quality of life [5]. Surgery is the optimal treatment for rectal prolapse, and about 100 procedures are known [6]. Surgical treatment approaches for rectal prolapse are traditionally divided into abdominal or perineal surgical approaches. It is still controversial whether the abdominal or perineal approach is superior in terms of postoperative complications and recurrence rates [7]. Although this disease can be treated through surgical methods, reports on the surgical management of recurrent rectal prolapse are insignificant [3]. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of surgical approaches for recurrent rectal prolapse.

This study was conducted at Chonnam National University Hospital from March 2016 to February 2021 on a total of 41 patients who underwent elective surgery for recurrent rectal prolapse. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chonnam National University Hospital (No. 2021-107) and written informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature.

The inclusion criteria of patients were as follows: (a) patients who underwent previous rectal prolapse surgery in our hospital; (b) patients 18 years and older; (c) patients diagnosed with recurrent rectal prolapse through additional examinations. The recurrence was evaluated by performing a digital rectal exam and/or defecography when the patient visited the outpatient clinic at 2 weeks and 3 months after surgery. Defecography was performed when abnormal findings were observed or the patient complained of recurrence of symptoms.

The patient’s baseline characteristics included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (PS) classification, type of previous surgery, and preoperative comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, lung disease, alcohol consumption, and smoking history). The follow-up period was defined as the period from the second surgery to the present, and the recurrence period was defined as the period from the first surgery to recurrence. Postoperative complications, such as urinary difficulty, ileus, bleeding, and sexual dysfunction, were obtained through physical examination and history taking during hospitalization after surgery and outpatient treatment after discharge.

In the case of recurrence after rectal prolapse surgery, the surgical procedures were performed with the opposite approaches considering the patient’s condition. If the patient initially underwent an abdominal approach, reoperation was performed with a perineal approach. When the risks of general anesthesia are high, such as when the patient is elderly, has a high ASA PS classification, or has a severe underlying disease, perineal approach surgery under spinal anesthesia was performed according to the recommendation of the anesthesiologist. For patients who underwent radiotherapy in the abdominal cavity, abdominal approach was selected. All elective rectal prolapse surgeries were performed by 2 experienced colorectal surgeons.

In general, the perineal approach to rectal prolapse is performed in fragile patients who cannot tolerate the abdominal approach, such as elderly patients, patients with severe heart or lung disease, patients at high risk of general anesthesia, or patients with a history of abdominal surgery. The authors performed Delorme procedure, Altemeier procedure, and the stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedure through a perineal approach, depending on the degree of rectal prolapse. The STARR procedure was used for mucosal prolapses less than 3 cm from the anus, Delorme procedure for prolapses larger than 3 cm, and Altemeier procedure for full-thickness prolapses.

All abdominal surgical approaches were performed using the laparoscopic ventral rectopexy method under general anesthesia regardless of the degree of rectal prolapse. All patients were placed in the lithotomy and Trendelenburg position after anesthesia, and a 12-mm trocar was inserted into the umbilicus for laparoscopic camera insertion, and four 5-mm trocars were inserted in each of the left and right upper and lower abdominal quadrants. The bowel was pulled out of the pelvis and the sigmoid colon was retracted to the left lateral side. The peritoneal opening was made in an inverted J-shape from the sacral cape to the left edge of the peritoneal reflex. The sterile polypropylene mesh (Prolene, Ethicon) was designed to have a length of 15 cm and a width of 2 cm. The mesh was properly positioned in the peritoneal opening, the lower end was sutured to the anterior wall of the rectum 2–3 cm from the edge of the anus, and the upper end was fixed to the right side of the periosteum of the sacral cape using ProTack (Covidien). The peritoneum opening was closed with continuous sutures using V-loc (Covidien) to prevent contact of the mesh with other organs in the abdomen.

The difference between the perineal approach group and the abdominal approach group was determined using Welch t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables, and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20.0 (IBM Corp.).

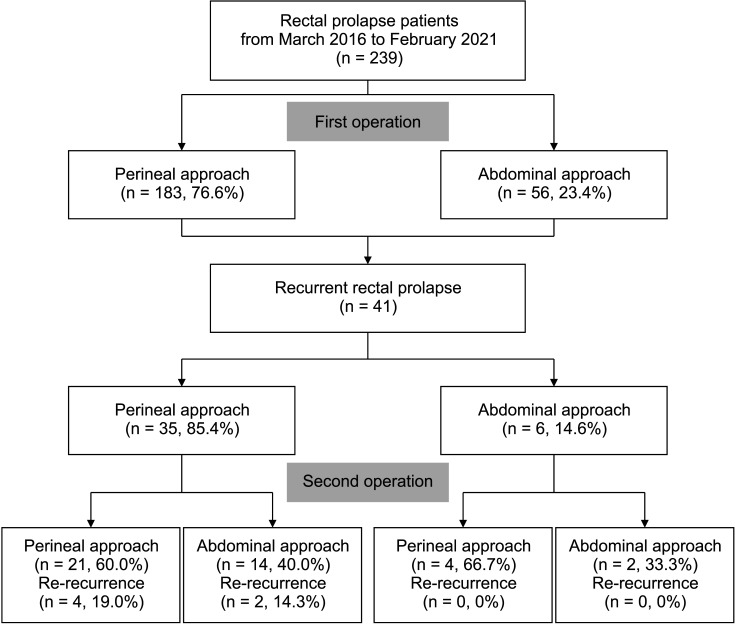

Among a total of 239 patients, 41 patients who underwent surgery for recurrent rectal prolapse were retrospectively enrolled from March 2016 to February 2021. Of the total 239 rectal prolapse patients, 183 patients (76.6%) were primarily operated on using the perineal approach and 56 patients (23.4%) were operated on using the abdominal approach. The recurrence rate of patients who underwent primary rectal prolapse was 19.1% (35 of 183) in the perineal approach and 10.7% (6 of 56) in the abdominal approach (P = 0.145) (Fig. 1).

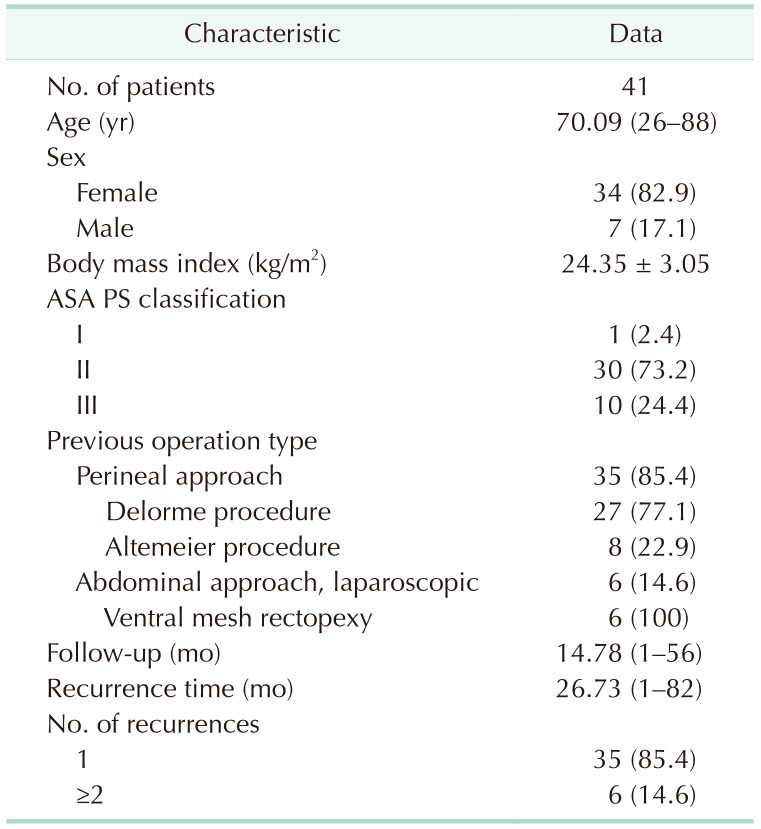

The median age of the patients with recurrent rectal prolapse was 70.09 years, and the proportion of female patients (82.9%) was higher than that of male patients. Among the previous operation types performed for rectal prolapse, Delorme procedure was the most common in 27 patients (77.1%). The median follow-up period was 14.78 months (range, 1–56 months), and the median recurrence period after the first operation was 26.73 months (range, 1–82 months) (Table 1).

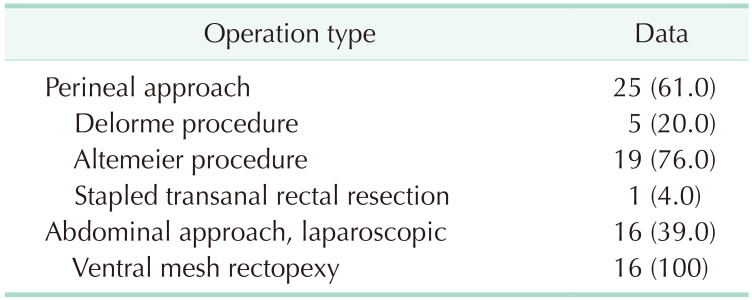

Recurrent rectal prolapses were surgically treated either by the perineal approach (n = 25, 61.0%) or by the abdominal approach (n = 16, 39.0%). In the perineal approach, the Altemeier procedure was most frequently performed in 19 patients (46.3%). All 16 patients who underwent an abdominal approach were operated on using the laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy method (Table 2).

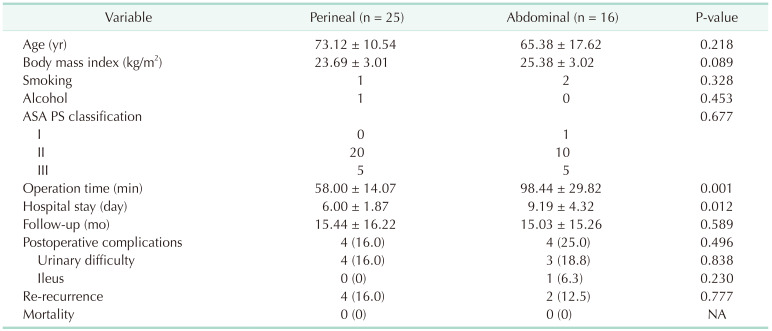

Patient characteristics were compared between the perineal approach group and the abdominal approach group that received additional surgical treatment for recurrent rectal prolapse. There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in variables such as patient’s age, BMI, ASA PS classification, alcohol consumption, and smoking history. The mean operation time was 98.44 ± 29.82 minutes in the abdominal approach group and 58.00 ± 14.07 minutes in the perineal approach group. There was a significant difference in the mean operation time between the 2 groups (P = 0.001). The mean hospital stay was 9.19 ± 4.32 days in the abdominal approach group and 6.00 ± 1.87 days in the perineal approach group. The mean hospital stay was significantly longer in the abdominal approach than in the perineal approach group (P = 0.012). Postoperative complications included 4 voiding difficulties (16.0%) in the perineal approach group, 3 voiding difficulties (18.8%) in the abdominal approach group, and 1 ileus difficulty (6.3%) in the abdominal approach group (P = 0.496). There were no additional postoperative complications such as bleeding, sexual dysfunction, wound infection, or reoperation between the 2 groups. The re-recurrence rate after repeat repair was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P = 0.777) (Table 3).

In this study, we retrospectively compared the clinical management outcomes of 41 of 239 patients with recurrent rectal prolapse at a single tertiary center for approximately 5 years. The recurrence rate after the first operation for rectal prolapse was 17.4% (perineal, 19.1% vs. abdominal, 10.7%), and 82.9% of the patients (34 of 41) were female. In previous studies, the prevalence of recurrent rectal prolapse after initial surgery was about 20%–30%, and it was reported that the majority were in women [8910].

Many studies have stated that the surgeons’ preference and patient risk factors are important in the decision-making process when choosing rectal prolapse surgery [1112]. We performed more perineal approaches (n = 25, 61.0%) than abdominal approaches (n = 16, 39.0%) for recurrent rectal prolapse. This reason can be found in the characteristics of patients with recurrent rectal prolapse. The average age of patients with recurrent rectal prolapse was 70.1 years, and the ASA PS classification was II or higher in most patients (n = 40, 97.6%). Because the patients were all elderly and frail, the risk of general anesthesia was high, so a perineal approach was performed for most recurrent rectal prolapse surgery. The abdominal approach was redone for 2 cases of recurrent rectal prolapse after abdominal approach (Fig. 1). These 2 patients had recurred rectal prolapse after radiotherapy for other malignant diseases (ovarian cancer and prostate cancer). We presumed that weakening of the mesh after radiotherapy may have contributed to the recurrence and decided to redo abdominal approach for these 2 patients. After applying new meshes, no recurrence or postoperative complications were noted.

We compared the 2 surgical methods for recurrent rectal prolapse, and the results showed a statistically significant difference in hospital stay and operation time. The mean hospital stay was 9.19 ± 4.32 days in the abdominal approach group, which was longer than 6.00 ± 1.87 days in the perineal approach group (P = 0.012). A recent multicenter retrospective study reported that postoperative hospital stay was statistically significantly longer in patients with recurrent rectal prolapse who underwent an abdominal approach (6.5 ± 2.6 days vs. 5.5 ± 2.8 days, P = 0.022) [13]. Solomon et al. [14] reported that the mean operation time was more than 50 minutes in the abdominal approach group compared to the peripheral approach group (P < 0.01). Our study had a similar result; the mean operation time was 98.44 ± 29.82 minutes in the abdominal approach group, longer than 58.00 ± 14.07 minutes in the perineal approach group (P = 0.001). Steele et al. [15] reported that the re-recurrence rate of recurrent rectal prolapse was lower in the abdominal approach than in the perineal approach (4 of 27, 14.8% vs. 19 of 51, 37.3%; P = 0.03). In this study, there was no statistically significant difference in the re-recurrence rates of the 2 surgical approaches for recurrent rectal prolapse (P = 0.777). Hong et al. [13] also stated that there was no significant difference in re-recurrence rates between the 2 surgical approaches (P = 0.203).

Postoperative complications included urinary difficulty in 4 patients in the perineal approach group, urinary difficulty in 3 patients in the abdominal approach group, and ileus difficulty in 1 patient (P = 0.496). All patients with complications recovered before discharge. There were no serious postoperative complications, reoperations, or deaths in both surgical approaches in this study.

The limitations of this study include the small number of patients and the short follow-up period. Therefore, additional multicenter studies on recurrent rectal prolapse with a longer follow-up period are continuously needed. In this study, the surgical approach of recurrent rectal prolapse was divided into 2 groups and compared, and the fact that all cases using the abdominal approach operated with the laparoscopic ventral rectopexy method did not present as a limitation.

Through this retrospective study conducted at a single tertiary hospital, we have an opportunity to provide clinical results regarding recurrent rectal prolapse, which lacks research reports, in line with an aging society.

In conclusion, there was no statistical significance in the re-recurrence rate and postoperative complications between the abdominal and perineal approach groups of recurrent rectal prolapse. Both surgical approaches can be good surgical options for the treatment of recurrent rectal prolapse.

Notes

References

1. Steele SR, Varma MG, Prichard D, Bharucha AE, Vogler SA, Erdogan A, et al. The evolution of evaluation and management of urinary or fecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Probl Surg. 2015; 52:92–136. PMID: 25933741.

2. Neshatian L, Lee A, Trickey AW, Arnow KD, Gurland BH. Rectal prolapse: age-related differences in clinical presentation and what bothers women most. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021; 64:609–616. PMID: 33496475.

3. Wijffels NA, Collinson R, Cunningham C, Lindsey I. What is the natural history of internal rectal prolapse? Colorectal Dis. 2010; 12:822–830. PMID: 19508530.

4. Michalopoulos A, Papadopoulos VN, Panidis S, Apostolidis S, Mekras A, Duros V, et al. Surgical management of rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2011; 15 Suppl 1:S25–S28. PMID: 21887563.

5. Bordeianou L, Hicks CW, Kaiser AM, Alavi K, Sudan R, Wise PE. Rectal prolapse: an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and patient-specific management strategies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014; 18:1059–1069. PMID: 24352613.

6. Formijne Jonkers HA, Draaisma WA, Wexner SD, Broeders IA, Bemelman WA, Lindsey I, et al. Evaluation and surgical treatment of rectal prolapse: an international survey. Colorectal Dis. 2013; 15:115–119. PMID: 22726304.

7. Emile SH, Elbanna H, Youssef M, Thabet W, Omar W, Elshobaky A, et al. Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy vs Delorme’s operation in management of complete rectal prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Colorectal Dis. 2017; 19:50–57. PMID: 27225971.

8. Senapati A, Gray RG, Middleton LJ, Harding J, Hills RK, Armitage NC, et al. PROSPER: a randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2013; 15:858–868. PMID: 23461778.

9. Kairaluoma MV, Kellokumpu IH. Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand J Surg. 2005; 94:207–210. PMID: 16259169.

10. Kim DS, Tsang CB, Wong WD, Lowry AC, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD. Complete rectal prolapse: evolution of management and results. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999; 42:460–469. PMID: 10215045.

11. Hool GR, Hull TL, Fazio VW. Surgical treatment of recurrent complete rectal prolapse: a thirty-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997; 40:270–272. PMID: 9118739.

12. Fengler SA, Pearl RK, Prasad ML, Orsay CP, Cintron JR, Hambrick E, et al. Management of recurrent rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997; 40:832–834. PMID: 9221862.

13. Hong KD, Hyun K, Um JW, Yoon SG, Hwang DY, Shin J, et al. Clinical outcomes of surgical management for recurrent rectal prolapse: a multicenter retrospective study. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2022; 102:234–240. PMID: 35475228.

14. Solomon MJ, Young CJ, Eyers AA, Roberts RA. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open abdominal rectopexy for rectal prolapse. Br J Surg. 2002; 89:35–39. PMID: 11851660.

15. Steele SR, Goetz LH, Minami S, Madoff RD, Mellgren AF, Parker SC. Management of recurrent rectal prolapse: surgical approach influences outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006; 49:440–445. PMID: 16465585.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download