Abstract

In mid-2022, as the wave of pediatric coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases escalated in South Korea, a public-private partnership was made to establish a Pediatric COVID-19 Module Clinic (PMC). We describe the utilization of the first prototype children’s modular clinic in Korea University Anam Hospital functioning as the COVID-19 PMC. Between August 1 and September 30, 2022, a total of 766 children visited COVID-19 PMC. Daily number of patient visits to the COVID-19 PMC ranged between 10 and 47 in August; and less than 13 patients per day in September 2022. Not only the model provided timely care for the COVID-19 pediatric patients, but it also enabled safe and efficacious care for the non-COVID-19 patients in the main hospital building while minimizing exposure risk to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 transmission. Current description highlights the importance of spatial measures for mitigating in-hospital transmission of COVID-19, in specifically on pediatric care.

Graphical Abstract

Emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected the healthcare utilization in various aspects. In South Korea, public health authority has partnered with private healthcare units with aligned interest to contain severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by way of hospital infection control methods—namely, early detection, isolation, and treatment. Hospital infection control measures were instituted with mission to minimize the risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 into the healthcare system as part of the national containment strategy.1 In early 2022, a new wave of COVID-19 due to omicron variant had been affecting the community, most notably, childhood population.2 The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on children had slow but deliberate effect on pediatric healthcare capabilities. However, still the national infection control policy was not lifted in the hospitals, and pediatric care system was left without an established triage system and methods of escalating levels of pediatric care. This resulted in the loss of adequate, timely care for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 pediatric patients and has created additional medical challenges.

In mid-2022, as the wave of pediatric COVID-19 cases escalated in South Korea, a public-private partnership was made to establish a Pediatric COVID-19 Module Clinic (PMC) in a private academic hospital. This COVID-19 PMC was to represent a prototype for an emergent childhood care facility, the evolution of modular hospital concept reflecting the change of epidemiology of COVID-19. In this paper, we describe the utilization of the first prototype children’s modular clinic in Korea University Anam Hospital functioning as the COVID-19 PMC, which was fully operational during the COVID-19 surge in mid-2022.

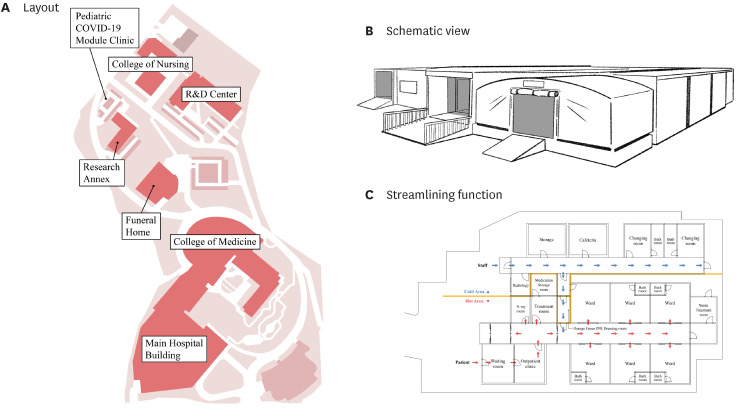

Korea University Anam Hospital is located on the northeast part of Seoul, covers an area of approximately 76,000 m2 on the Nokji Campus of Korea University (Fig. 1A). The COVID-19 PMC was built on a parking lot area on Nokji Campus, approximately 600 m away straight distance from the front gate of main hospital building. The construction of prefabricated COVID-19 PMC elements was done offsite, which then followed the onsite installation of components (Fig. 1B and C). The modular facility includes six modules in different size (15.3 × 18.0 m; 6.0 × 9.7 m; 6.0 × 18 m; 8.4 × 9.0 m; 5.0 × 12.0 m; 5.0 × 14.0 m) attached to form a rectangular building, which were constructed, delivered, and assembled within 4 weeks of period. The COVID-19 PMC has layout design divided into three zones: cold (clean), orange fence (potential contaminated), and hot (contaminated) zones, which were isolated from each other and were interconnected with channels (Fig. 1C). The cold zone includes staff's changing room, cafeteria, and storage facility. The hot zone is composed of patient waiting room, outpatient clinic, treatment room, and six isolation wards, which is interconnected with orange fence before entering the cold zone. Supplementary Table 1 shows the roles and responsibilities of hospital leadership liaison, PMC director, pediatrician-in-chief, and the COVID-19 PMC operation teams. Estimated capacity of patient visit was less than 50 per day; and one pediatrician (from a team of five), three nurses, one radiology technician and one administrative personnel were deployed each day. Fully functional outpatient pediatric care was available, including intravenous fluid and medications, nebulizers, and X-rays. Those who required overnight hospitalization, the patient was then transferred to the main hospital's pediatric isolation ward for further treatment and care.

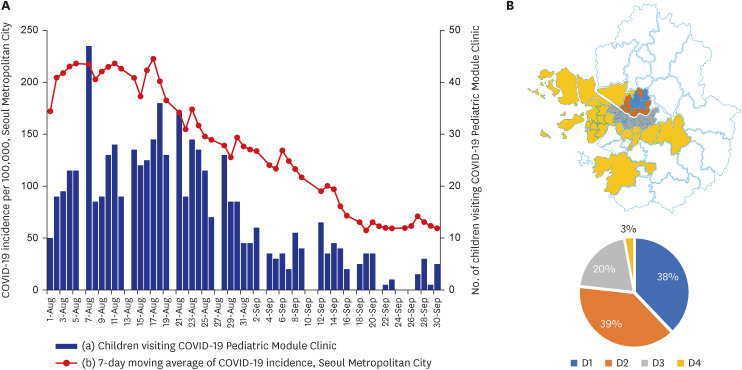

The COVID-19 PMC became active from August 1 to September 30, 2022, during the peak wave of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.5 prevailed in the country. The 7-day moving average of COVID-19 incidence in Seoul ranged between 150 and 230 per 100,000 in August, which then fell to 50–100 per 100,000 in September 2022 (Fig. 2A). Between August 1 and September 30, 2022, a total of 766 children visited COVID-19 PMC. Daily number of patient visits to the COVID-19 PMC ranged between 10 and 47 in August; and less than 13 patients per day in September 2022 (Fig. 2A). The mean age was 4.6 years (range, 2 months–18 years), 55% were boys and 45% were girls. Two hundred eighty-five (37%) received intravenous fluid therapy, 135 (18%) took chest X-rays, and 62 (8%) required hospitalization. Lower respiratory tract infection including croup was suspected in was diagnosed in 161 patients (21%). 38% of the patients were from neighboring district (D1, Dongdaemun-gu, Seongbuk-gu, Nowon-gu, Gangbuk-gu, Jongno-gu), while 39% were from districts 10–15 kms away from the COVID-19 PMC (D2, Seongdong-gu, Mapo-gu, Jungnang-gu, Dobong-gu, Yongsan-gu, Jung-gu, Gwangjin-gu, Seodaemun-gu, Eunpyeong-gu), 20% from distant districts (D3, Seongpa-gu, Gangnam-gu, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Gangdong-gu, Seocho-gu, Gangseo-gu, Dongjak-gu, Gwanak-gu, Yangcheon-gu, Guro-gu, Geumcheon-gu), and 3% from non-Seoul Metropolitan city (D4, Seongnam, Uiwang, Incheon, Goyang, Gwacheon, Gwangju, Hwaseong, Gwangmyeong, Gimpo, Bucheon, Anyang; Fig. 2B).

According to World Health Organization classification and minimum standards for emergency medical teams (also known as ‘BlueBook 2021’), COVID-19 PMC could be categorized ‘type 1, fixed’ with specialized care teams for pediatrics and disease outbreak.3 Initially, in planning stage, PMC have been designed for daytime admission unit, therefore the equipment and layout were almost met the requirement to type 2 emergency medical team unit which can be operate 24 hours and has capability to inpatient acute care. However, lack of manpower made the unit to be operated only 12 hours/days and sequential tapering as patient decreased. If 24 hours 7 days operation would be available, the result could be even remarkable. But it was almost impossible to recruit proper medical professional for the task.

Another remarkable aspect of current COVID-19 PMC experience is, sharing and utilization of basic resource of Korea University Anam Hospital. Using pre-existing and well-established tertiary center’s infrastructure gave great advantage to operate emergency unit in many aspects. Such as, critically ill patient care, transfer out processing, medical supplies, and the order and medical record managing systems.

Responding to COVID-19 pandemic is a continual process that requires swift intervention upon change in disease epidemiology. The building of COVID-19 PMC was aimed to mitigate the spatial and functional constraints of creating isolation spaces in the main hospital building, while containing the virus from the vulnerable population in hospital setting.4 Although having a significant cost and operational implication, a partnership between the public and private sectors enabled utilization of COVID-19 PMC during the surge of pediatric cases, as noted in previous reports in Korea.56

Not only the model provided timely care for the COVID-19 pediatric patients, but it also enabled safe and efficacious care for the non-COVID-19 patients in the main hospital building while minimizing exposure risk to SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The use of modular approaches has been adopted by many hospitals across high-income countries that include repurposing medical and non-medical buildings, and remote adjustments.7 While those approaches were aimed to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 during the period of surge capacity, our COVID-19 PMC model was essential to deliver efficient care in COVID-19 pediatric patients during the changed epidemiology following introduction of new SARS-CoV-2 variant.

Although expanding healthcare access to primary care clinics was found to be effective for improved care, COVID-19 PMC was resourceful for escalating care in pediatric COVID-19 patients requiring further management including intravenous hydration for children with decreased fluid intake, respiratory care for children with respiratory difficulties, and close monitoring for newborns or infants with continued fevers.

Current description highlights the importance of spatial measures for mitigating in-hospital transmission of COVID-19, in specifically on pediatric care. Although children are known to be less severely affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to adults, surge in number of cases (or denominator) inevitably leads to proportionally higher number of severe cases (or nominator) among pediatric population. While COVID-19 PMC was effective in providing escalated care in children, scaling up of such model may not be feasible given the limited resources in pediatric care.

In countries such as Korea, where the population is aging and the number of infants and young children is decreasing, there is a problem of a decrease in the number of pediatricians. As a result, COVID-19 infants and young children may not be able to receive proper pediatric care in emergency situations. Therefore, national support is needed for the training and placement of pediatricians. In addition to the apparent difference in risk of COVID-19 between pediatric and adult patients, there are a number of other considerations. During the omicron phase of COVID-19 pandemic, there have been changes in the disease phenotypes in children; with more croup patients and less of severe sepsis-like features. Despite the changes, the increased burden from croup have posed a significant clinical challenge in the outpatient setting. Given the COVID-19 PMC was designed to provide both urgent and emergent care to the patients, a portion of health access gap from the changed epidemiology, likely had been filled from the operation of PMC.

COVID-19 pandemic continuously poses different challenges at different phases. Most academic healthcare services have managed its infection control policy with a strong commitment to contain the SARS-CoV-2 spread to minimize health service disruption.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Korea University Anam Hospital’s leadership group, nursing team, radiology team, and all other operation units who worked and managed the Pediatric COVID-19 Module Clinic. Korea University Medical Library helped to support illustration of figures presented in this manuscript. We also thank Seoul Metropolitan Government for their administrative support.

Notes

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Choe YJ, Lee JS, Park JE.

Data curation: Choe YJ, Lee Y, Park KH.

Formal analysis: Choe YJ.

Methodology: Choe YJ, Park JE.

Supervision: Im GJ, Lee SW, Park JE.

Validation: Choe YJ, Lee JS, Lee Y, Park KH, Yoo Y.

Writing - original draft: Choe YJ.

Writing - review & editing: Lee JS.

References

1. Jang W, Kim B, Kim ES, Song KH, Moon SM, Lee MJ, et al. Differences in strategies for prevention of COVID-19 transmission in hospitals: nationwide survey results from the Republic of Korea. J Hosp Infect. 2022; 129:22–30. PMID: 35998837.

2. Choi YY, Kim YS, Lee SY, Sim J, Choe YJ, Han MS. Croup as a manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant infection in young children. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(20):e140. PMID: 35607737.

3. World Health Organization. Classification and Minimum Standards for Emergency Medical Teams. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2021.

4. Cheng A, Chen Y, Gao Y, Sun P, Chang R, Zhou B, et al. Mobile isolation wards in a fever clinic: a novel operation model during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol Infect. 2021; 149:e61. PMID: 33622421.

5. Ku SS, Choe YJ. A public-private partnership model to build a triage system in response to a COVID-19 outbreak in Hanam City, South Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020; 11(5):339–342. PMID: 33117640.

6. Park J, Chung E. Learning from past pandemic governance: early response and public-private partnerships in testing of COVID-19 in South Korea. World Dev. 2021; 137:105198. PMID: 32982017.

7. Ndayishimiye C, Sowada C, Dyjach P, Stasiak A, Middleton J, Lopes H, et al. Associations between the COVID-19 pandemic and hospital infrastructure adaptation and planning-a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(13):8195. PMID: 35805855.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 1

Roles and responsibilities in the operation of PMC, Korea University Anam Hospital

Fig. 1

Illustration of the Pediatric COVID-19 Module Clinic in Korea University Anam Campus. (A) Layout, (B) schematic view, and (C) streamlining function of the clinic.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Fig. 2

Monitoring of pediatric patients with COVID-19 during August and September 2022. (A) Daily number of (a) children visiting COVID-19 Pediatric Module Clinic, Korea University Anam Hospital, and (b) 7-day moving average of COVID-19 incidence per 100,000, Seoul Metropolitan City. (B) Geographical distribution of patients visiting COVID-19 Pediatric Module Clinic.

D1, Dongdaemun-gu, Seongbuk-gu, Nowon-gu, Gangbuk-gu, Jongno-gu; D2, Seongdong-gu, Mapo-gu, Jungnang-gu, Dobong-gu, Yongsan-gu, Jung-gu, Gwangjin-gu, Seodaemun-gu, Eunpyeong-gu; D3, Seongpa-gu, Gangnam-gu, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Gangdong-gu, Seocho-gu, Gangseo-gu, Dongjak-gu, Gwanak-gu, Yangcheon-gu, Guro-gu, Geumcheon-gu; D4, non-Seoul area (Seongnam, Uiwang, Incheon, Goyang, Gwacheon, Gwangju, Hwaseong, Gwangmyeong, Gimpo, Bucheon, Anyang).

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download