Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to investigate the trend of domestic medical travel from non-Seoul areas to Seoul for initial breast cancer treatment, and identify factors associated with medical travel in breast cancer patients.

Methods

A nationwide retrospective cohort study was performed using the Health Insurance Review and Assessment data of South Korea. Patients were classified according to the regions in which they underwent breast biopsy (Seoul vs. metropolitan cities vs. other regions). Frequencies of biopsy, diagnosis, treatment, and domestic medical travel were analyzed according to regions, and factors associated with medical travel were investigated.

Results

A total of 150,709 breast cancer survivors who were diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2017 were included. The total rate of medical travel from non-Seoul regions to Seoul had increased from 14.2% (1,161 of 8,150) in 2010 to 19.8% (2,762 of 13,964) in 2017. Approximately a quarter of patients from other regions traveled to Seoul, and over 40% of patients from Chungbuk, Gyeongbuk, and Jeju regions traveled to Seoul for initial treatment in 2017. The difference in the annual frequencies of upfront surgery between Seoul and non-Seoul regions increased over time. Younger age and regions other than metropolitan cities were significantly related to medical travel. Patients covered by medical aid or past medical histories were significantly less likely to travel to Seoul for initial breast cancer treatment.

Go to :

The incidence of breast cancer has rapidly increased and breast cancer has become the major type of cancer among women worldwide [12]. In South Korea, more than 26,000 patients were newly diagnosed with breast cancer in 2017 [3], which led to increased demands for breast cancer surgery and other adjuvant treatments [4].

Multidisciplinary approaches and timely access to definitive care are important for improving breast cancer outcomes [567]. There is substantial evidence that a treatment delay of 3 months or more in breast cancer patients is associated with a lower survival rate [5]. One of the factors that can affect delay in treatment is domestic medical travel, which is moving from one region to other regions for treatment.

Studies on domestic medical travel have been conducted primarily for cancers other than breast cancer [8910]. In South Korea, medical travel from non-capital regions to Seoul for cancer treatments has been increasing [111213]. However, little is known about the trend of medical travel for breast cancer patients in South Korea. Therefore, we conducted a nationwide retrospective cohort study using the national claims data to investigate the patterns and frequencies of initial breast cancer treatments by region, assess domestic medical travel over time, and identify the factors associated with medical travel in breast cancer patients.

Go to :

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (No. 2020-1769). It was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and written informed consent was waived due to its retrospective nature.

The Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) assesses the medical services provided in South Korea and determines their reimbursement. Accordingly, the HIRA database archives the nationwide claims data from all healthcare providers and provides the data in 6 domains including general information, healthcare services, prescriptions, diagnosis, medication information, and provider information [14]. The diagnosis data is archived using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). The V193 code is a specialized claim code for reimbursement based on which hospitals are reimbursed for cancer treatment by the Korean government.

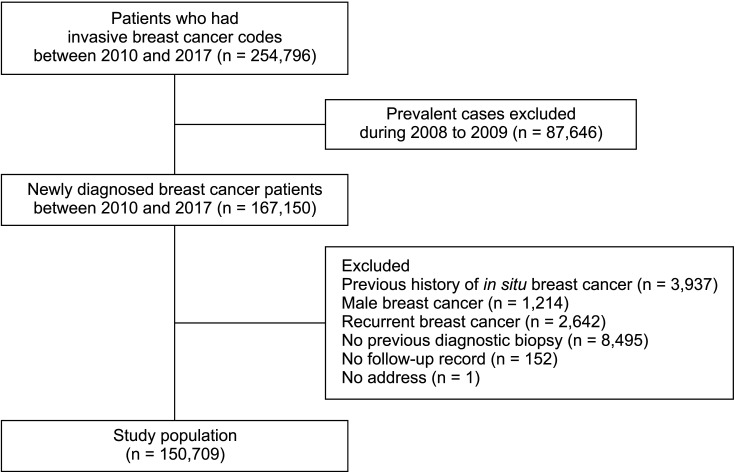

We extracted all available data of 254,796 patients who were coded with the ICD-10 C50 and V193 codes between January 2010 and December 2017. To exclude prevalent cases, we discarded cases between January 2008 and December 2009 (n = 87,646). A total of 167,150 newly diagnosed breast cancer patients were identified. Of them, we excluded cases of male breast cancer (n = 1,214), history of ductal carcinoma in situ (n = 3,937), recurrent breast cancer (n = 2,642), absence of previous diagnostic biopsy (n = 8,495), absence of follow-up record (n = 152), and absence of the record of the medical facility where the biopsy was performed (n = 1) (Fig. 1).

The basic demographics of the patients and their Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) using ICD-10 codes were analyzed [15]. Medical histories such as hypertension (I10–13, 15), diabetes mellitus (E10–14), and dyslipidemia (E78) were defined using the relevant ICD-10 codes combined with medications.

Biopsy for breast cancer diagnosis was defined with the pathologic examination claims codes (C5509, C5911–C5917, C5500, C5504, C5508). The date of biopsy was defined as the latest date among the dates when pathologic exam claims codes were recorded prior to breast cancer diagnosis. The date of breast cancer diagnosis was defined as the first date when C50 plus V193 codes were recorded. Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, and trastuzumab were defined based on the claims data recorded within 1 year after diagnosis.

Geographic regions were categorized into Seoul, metropolitan cities (Daegu, Daejeon, Gwangju, Incheon, Busan, and Ulsan), and other regions (Chungbuk, Chungnam, Gangwon, Gyeongbuk, Gyeonggi, Gyeongnam, Jeju, Jeonbuk, Jeonnam, and Sejong). Subjects were classified into 3 groups according to the regions in which they underwent biopsy.

Baseline characteristics were presented according to the regions where biopsy was performed. The annual frequencies of biopsy, diagnosis, and initial treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation) for breast cancer by geographic region were analyzed. The numbers and proportions of patients who underwent biopsy in non-Seoul areas traveling to Seoul for initial breast cancer treatment were analyzed. Factors associated with domestic medical travel from non-Seoul regions to Seoul were analyzed using a multivariable logistic regression model adjusted by age at diagnosis, insurance (health insurance vs. medical aid), CCI, region where the pathologic exam was performed (metropolitan cities vs. other regions), and year (from 2010 to 2017).

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software ver. 9.4.2 (SAS Institute) and R software ver. 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; http://www.r-project.org).

Go to :

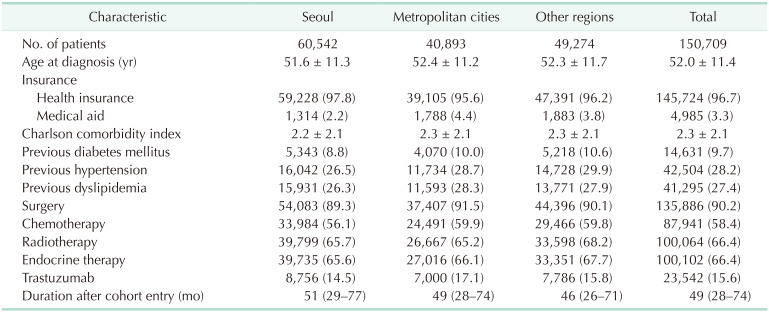

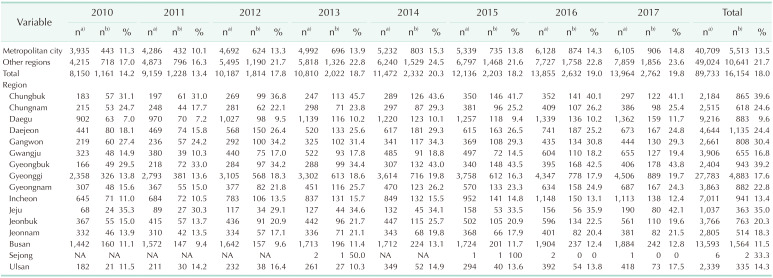

A total of 150,709 patients diagnosed with breast cancer between January 2010 and December 2017 were included in this analysis (Table 1). Of the patients, 135,886 (90.2%) underwent surgery. The proportions of breast cancer patients who received chemotherapy and radiotherapy were 58.4% and 66.4%, respectively. During the study period, 60,542 (40.2%) patients were diagnosed with breast cancer in Seoul.

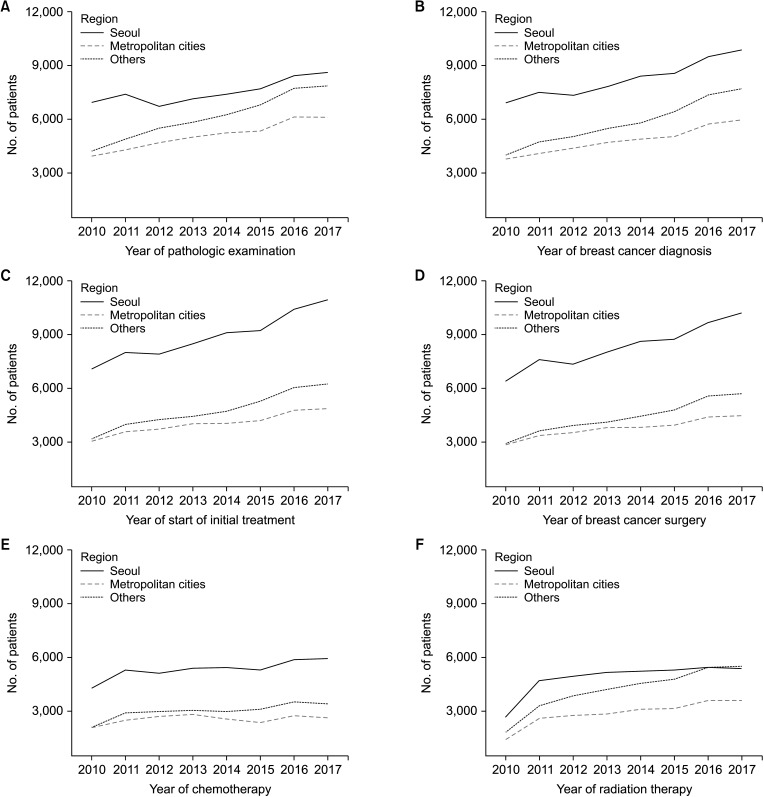

From 2010 to 2017, the annual frequencies of pathologic exams, diagnosis, and treatment for breast cancer increased in all regions (Fig. 2). The difference in the annual frequencies of pathologic examination and diagnosis between Seoul and other regions decreased over time (Fig. 2A, B). However, the difference in the annual frequencies of initial treatment and surgery between Seoul and non-Seoul regions increased over time (Fig. 2C, D). The difference in the annual frequencies of chemotherapy and radiotherapy between Seoul and non-Seoul regions did not increase over time (Fig. 2E, F).

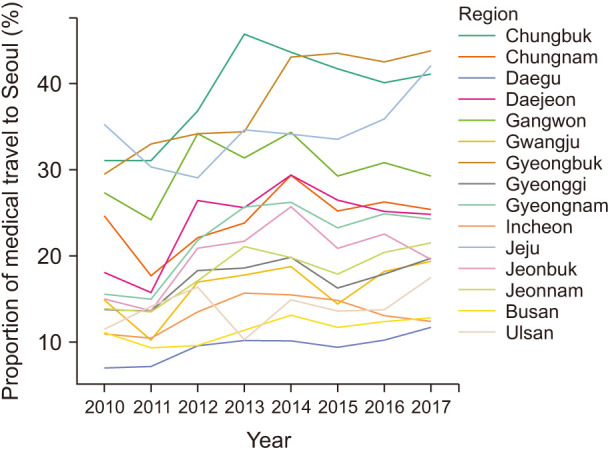

Among the patients who underwent biopsy in non-Seoul regions, after excluding 434 patients without a record on the date of pathologic exam, the rate of domestic medical travel from non-Seoul regions to Seoul for initial treatment increased from 14.2% (1,161 of 8,150) in 2010 to 19.8% (2,762 of 13,964) in 2017 (Table 2). Approximately a quarter of patients (23.6%) from other regions traveled to Seoul in 2017. Especially, more than 40% of breast cancer patients who underwent biopsies in Chungbuk, Gyeongbuk, and Jeju regions traveled to Seoul in 2017 (Fig. 3).

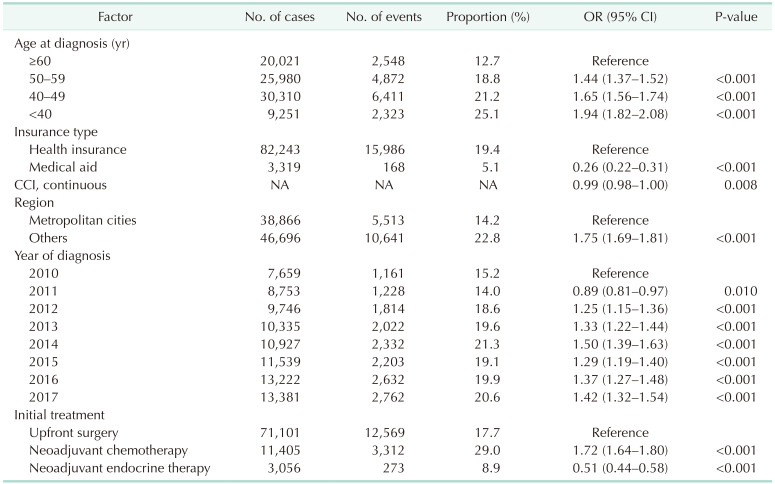

After excluding 4,171 patients who did not receive any treatment, multivariable logistic regression analyses showed age younger than 40 years (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.00–2.28; P < 0.001) was significantly associated with a higher likelihood for domestic medical travel to Seoul for breast cancer treatment (Table 3). Patients registered with medical aid (OR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.23–0.31; P < 0.001) and those with other medical diseases (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97–0.99; P < 0.001) were significantly less likely to travel to Seoul. Patients who underwent pathologic examination in other regions were significantly more likely to travel to Seoul than those who underwent an examination in metropolitan cities (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.71–1.84; P < 0.001).

Go to :

This study showed that domestic medical travel for breast cancer treatment from non-Seoul regions to Seoul increased over time in South Korea. In some regions, more than 40% of the patients traveled to Seoul for breast cancer treatment in 2017. Young patients and patients in other regions were more likely to travel to Seoul after biopsy. Patients covered by medical aid or those with other medical diseases were less likely to travel to Seoul. To our knowledge, this is the first nationwide study to investigate the trend in domestic medical travel of breast cancer patients in South Korea.

A previous study showed the medical travel to Seoul for lung cancer surgery in South Korea [11], as the proportion of lung cancer surgeries significantly increased over time in Seoul while the proportion in other areas decreased. For prostate cancer, 1 study showed that the frequencies of medical travel from non-Seoul regions to Seoul for treatment decreased from 2005 to 2014, although a large proportion of medical travel remained unchanged [13]. Another study in the United States was conducted to investigate the impact of centralizing rectal cancer surgeries to high-volume centers [10], which showed that there was a statistically significant increase in the average distance traveled by patients during a 10-year period, indicating that centralization might add to the travel burden of patients.

Medical travel for cancer treatment is an important issue for patients and healthcare providers alike because there is a risk of prolonged waiting time for treatment. Delay in the start of treatment often causes anxiety, reduces the quality of life, adversely affects mental health, and may lead to detrimental effects on survival [16]. In breast cancer, prolonged time from diagnosis to surgery may decrease cancer-specific survival as well as overall survival [67]. Delayed chemotherapy can be associated with poor prognosis, both in the adjuvant setting [1718] and in the metastatic setting [19].

The present study describes the patterns of medical travel of more than 150,000 patients diagnosed with breast cancer in different regions of South Korea during a 7-year period. We found that young age, insurance type, and previous medical disease were the most important factors associated with medical travel from outside Seoul to Seoul. Medical travel to Seoul for treatment was more common in younger age groups, and the number of patients in their 30s was more than double that of patients aged 60 years or older. A similar trend was also observed in other types of cancers, such as prostate cancer or head and neck cancer [1320]. In our study, the OR for medical travel in patients on medical aid was 1/4 of that in patients with health insurance. Similar to the results of our study, 1 study conducted on parathyroid surgery in the United States reported that the proportion of domestic medical travelers (defined as patients who underwent parathyroidectomy at a hospital in a different United States region from the one in which they resided and traveled more than 150 miles to that hospital) was higher in patients with insurance (62.1%) than in those with Medicare (32.4%) or Medicaid/uninsured (0.3%) [2].

An interesting finding of the present study is that the proportion of patients receiving initial treatment in Seoul increased over time, but this differed depending on the treatment type (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy). The proportion of patients receiving treatment in Seoul increased sharply over time in the case of surgery, while only a modest increase was noted for chemotherapy; in contrast, the proportion of patients receiving radiotherapy increased rapidly in regions other than Seoul. A possible explanation for this discrepancy according to treatment type is the frequency of treatment; while surgery is a 1-time treatment, chemotherapy requires visits every 1–3 weeks for more than 3 months; moreover, radiotherapy requires daily visits, which makes it less likely for patients to travel outside their residential region for treatment.

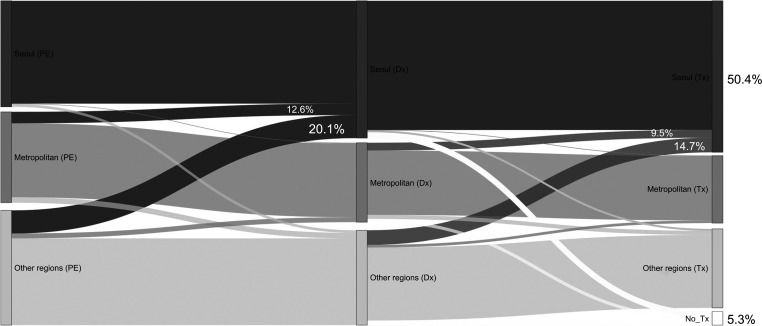

Breast cancer patients can also travel from Seoul to non-Seoul areas for breast cancer treatment. Fig. 4 demonstrates comprehensive patterns of medical travel for breast cancer treatment. Based on 3 time points (date of pathologic exam following breast biopsy, date of breast cancer diagnosis, and date of initiation of treatment), it shows that compared to proportions of medical travel from non-Seoul to Seoul, those of medical travel from Seoul to metropolitan cities or other areas were low. Interestingly, 5.3% of breast cancer patients did not get any treatment within 1 year after diagnosis.

The Korean government initiated the Regional Cancer Center Support Program in 2004 as regional inequality in cancer care was getting worse. As of today, 12 university hospitals have been designated as Regional Cancer Centers to improve the quality of cancer care in the regions and reduce regional inequalities of cancer treatment in Korea. However, this study showed, despite all these financial supports from the government, medical travel to Seoul for breast cancer treatment has still been increasing. The reason for increasing medical travel to Seoul is not clear. Future studies may be needed to investigate the gaps in treatment quality throughout the centers.

The limitations of this study should be noted. First, the actual address of the patients’ residences could not be identified because the HIRA data is based on claims data. Thus, we categorized patients based on the regions where the pathologic examinations were performed instead of the patients’ residences. Second, there are several potential factors associated with medical travel that were not included in the HIRA data, such as socioeconomic status, transportation, and route of information. For a more detailed investigation into the reason for medical travel, a subsequent questionnaire study will be conducted. Third, although the present study showed medical travel for breast cancer treatment in South Korea, wait time for breast cancer treatment was not investigated. The issues of medical travel to Seoul for breast cancer treatment are not only just about centralization but also about time delay to treatment and the effect on survival. Further studies are needed to assess whether increased medical travel rates to Seoul lead to delays in treatment and cause harmful effects on breast cancer survival. However, this study is more about inequality of breast cancer treatment between Seoul and non-Seoul areas. The increasing medical travel to Seoul itself indicates the imbalance of demand and supply of cancer care in the country. In addition, the HIRA data did not include the stage of cancer, and survival analysis could not be performed accordingly. Lastly, it was not clear in this study whether the reason patients moved to Seoul for treatment was that there were therapeutic benefits such as a standard level of treatment. In countries like Korea, where all insurance companies are government, and in countries where transportation costs are more problematic than the cost of medical care, national policies are inevitably important, and a consensus is required as a policy.

In conclusion, medical travel to Seoul for upfront breast cancer surgery has been increasing over time. Increasing medical travel poses not only a medical problem but also a social problem. Policies for appropriate healthcare delivery need to be established in the near future.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We express our gratitude to the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service for providing the nationwide claims data.

Go to :

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018; 68:394–424. PMID: 30207593.

2. Hinson AM, Hohmann SF, Stack BC. Domestic travel and regional migration for parathyroid surgery among patients receiving care at academic medical centers in the United States, 2012-2014. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016; 142:641–647. PMID: 27124618.

3. Kang SY, Kim YS, Kim Z, Kim HY, Kim HJ, Park S, et al. Breast cancer statistics in Korea in 2017: data from a breast cancer registry. J Breast Cancer. 2020; 23:115–128. PMID: 32395372.

4. Chung IY, Lee J, Park S, Lee JW, Youn HJ, Hong JH, et al. Nationwide analysis of treatment patterns for Korean breast cancer survivors using National Health Insurance Service data. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33:e276. PMID: 30369858.

5. Richards MA, Westcombe AM, Love SB, Littlejohns P, Ramirez AJ. Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet. 1999; 353:1119–1126. PMID: 10209974.

6. Yun YH, Kim YA, Min YH, Park S, Won YJ, Kim DY, et al. The influence of hospital volume and surgical treatment delay on long-term survival after cancer surgery. Ann Oncol. 2012; 23:2731–2737. PMID: 22553194.

7. Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, Beck JR, Ross E, Wong YN, et al. Time to surgery and breast cancer survival in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016; 2:330–339. PMID: 26659430.

8. Stitzenberg KB, Sigurdson ER, Egleston BL, Starkey RB, Meropol NJ. Centralization of cancer surgery: implications for patient access to optimal care. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27:4671–4678. PMID: 19720926.

9. Shalowitz DI, Nivasch E, Burger RA, Schapira MM. Are patients willing to travel for better ovarian cancer care? Gynecol Oncol. 2018; 148:42–48. PMID: 29079037.

10. Xu Z, Aquina CT, Justiniano CF, Becerra AZ, Boscoe FP, Schymura MJ, et al. Centralizing rectal cancer surgery: what is the impact of travel on patients? Dis Colon Rectum. 2020; 63:319–325. PMID: 32045397.

11. Park S, Park IK, Kim ER, Hwang Y, Lee HJ, Kang CH, et al. Current trends of lung cancer surgery and demographic and social factors related to changes in the trends of lung cancer surgery: an analysis of the national database from 2010 to 2014. Cancer Res Treat. 2017; 49:330–337. PMID: 27456943.

12. Hong NS, Lee KS, Kam S, Choi GS, Kwon OK, Ryu DH, et al. A survival analysis of gastric or colorectal cancer patients treated with surgery: comparison of capital and a non-capital city. J Prev Med Public Health. 2017; 50:283–293. PMID: 29020762.

13. Kim JH, Kim SY, Yun SJ, Chung JI, Choi H, Yu HS, et al. Medical travel among non-Seoul residents to seek prostate cancer treatment in medical facilities of Seoul. Cancer Res Treat. 2019; 51:53–64. PMID: 29458236.

14. Kim JA, Yoon S, Kim LY, Kim DS. Towards actualizing the value potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) data as a resource for health research: strengths, limitations, applications, and strategies for optimal use of HIRA data. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32:718–728. PMID: 28378543.

15. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005; 43:1130–1139. PMID: 16224307.

16. Song H, Fang F, Valdimarsdóttir U, Lu D, Andersson TM, Hultman C, et al. Waiting time for cancer treatment and mental health among patients with newly diagnosed esophageal or gastric cancer: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2017; 17:2. PMID: 28049452.

17. Lohrisch C, Paltiel C, Gelmon K, Speers C, Taylor S, Barnett J, et al. Impact on survival of time from definitive surgery to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:4888–4894. PMID: 17015884.

18. Chavez-MacGregor M, Clarke CA, Lichtensztajn DY, Giordano SH. Delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016; 2:322–329. PMID: 26659132.

19. Ho PJ, Cook AR, Binte Mohamed Ri NK, Liu J, Li J, Hartman M. Impact of delayed treatment in women diagnosed with breast cancer: a population-based study. Cancer Med. 2020; 9:2435–2444. PMID: 32053293.

20. Lamont EB, Hayreh D, Pickett KE, Dignam JJ, List MA, Stenson KM, et al. Is patient travel distance associated with survival on phase II clinical trials in oncology? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003; 95:1370–1375. PMID: 13130112.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download