Abstract

Teratomas are benign germ cell tumors that usually found out of their anatomical origin. Teratomas usually are found in sacrococcygeal area, gonads, mediastinum, cervicofacial region and intracranial fossa. Spinal teratomas are rare. In this study we describe a case of conus medullaris teratoma which was diagnosed based on imaging studies. The patient underwent surgery. We did bilateral laminectomy. The mass lesion had an obvious and rigid attachment to the conus medullaris. The wall of the lesion was resected as much as possible, but total resection of the lesion's wall could not be done due to changes in neural monitoring. Previous related studies are reviewed.

Teratomas are benign germ cell tumors which include embryonic ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. They are usually found out of their anatomical origin [1]. They comprise 3–5% of childhood tumors and about 20% are malignant [2].

Teratomas can appear in all midline sites, but usually are found in sacrococcygeal area, gonads, mediastinum, cervicofacial region, and intracranial fossa. About 2% are seen in central nervous system and a small proportion of these cases are found in spinal cord [34]. Teratoma comprise about 0.2–0.5% of all spinal tumors. In the infancy they are mostly found in sacrococcygeal area and they almost have extramedullary extension. Intradural expansion of these tumors and spinal cord involvements are only reported in few cases [35]. In this study we describe a case of conus medullaris teratoma.

A 12-year-old girl was referred because of progressive gait impairment and back pain since 4 months ago. In the physical examination, deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) of lower extremities were normal and had no sphincter disorders. She had gait disorder as bradykinesia and was obviously incapable of fast movements. Lower extremity force was 4/5.

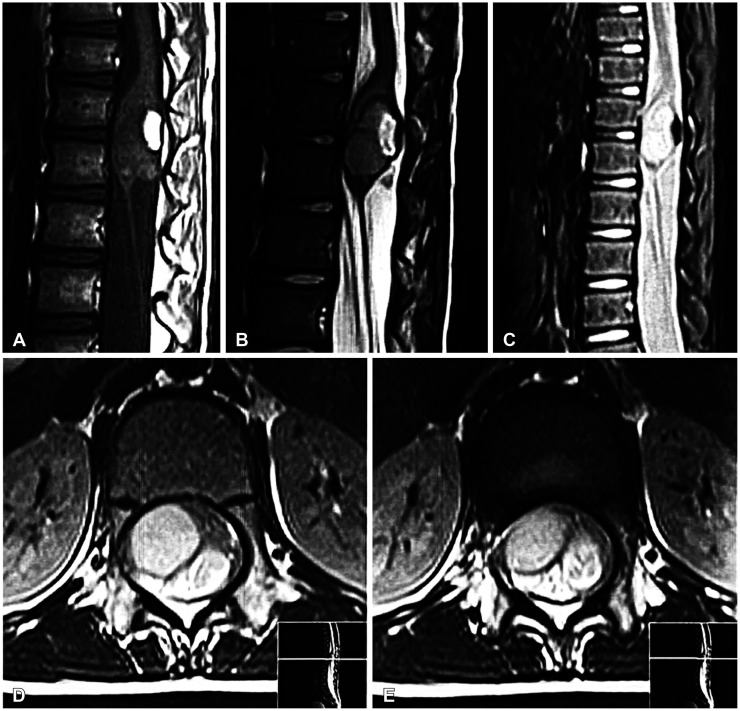

In the imaging studies and dorsolumbar MRI, a hetrogenous well-defined intradural intramedullary mass in connus medullaris was found. A hypersignal area in T1W images consistent with fat was noted, so teratoma was included in the differential diagnosis (Fig. 1). The patient underwent surgery with a possible diagnosis of a conus medullaris teratoma.

In the operating room, the patient underwent general intravenous anesthesia. After connecting the neuromonitoring leads-somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) and motor evoked potential (MEP), we utilized warming blankets to prevent intraoperative hypothermia. We also used narcotics and propofol to prevent disturbance in patient's neuromonitoring.

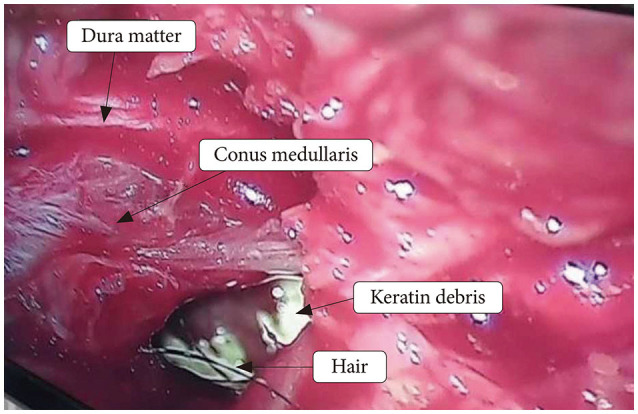

After mapping the site of surgery by using C-arm, we did bilateral laminectomy of T12 and L1 by using micro-drill and kerison ronguer (number 2 and 3). The mass lesion had an obvious and rigid attachment to the conus medullaris (Fig. 2). First we tried for total en bloc resection of the tumor, but internal decompression was done due to temporary changes in MEP and SSEP (decreased amplitude and increased latency) that occurred during the surgery. As the tumor was severely attached to the conus medullaris and filum terminale, cutting the filum terminal was not possible. After incising over the lesion, yellowish liquid containing patches of hair and small white solid tissues was found and then drained totally and specimens were sent for pathologic evaluations. The procedure last approximately 120 minutes.

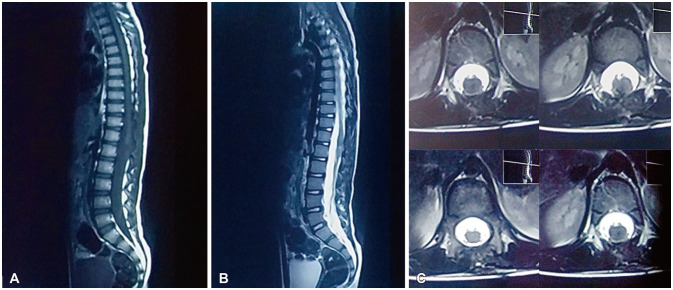

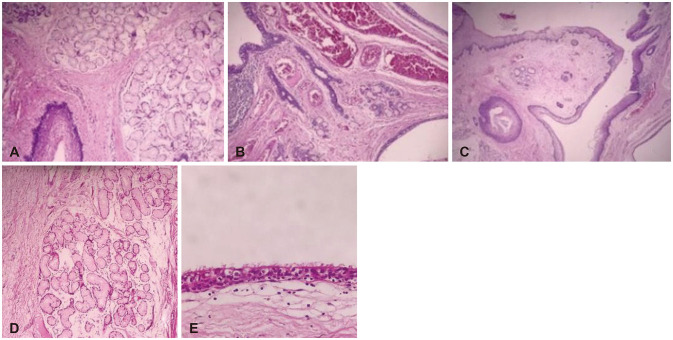

After the surgery no complication and no new motor neurologic deficits were noted and follow up showed no residual tumoral tissue (Fig. 3). Pathologic report confirmed the diagnosis of teratoma (Fig. 4). In the four month follow up after the surgery patient has no pain and her gate became normal.

As the patient was under 18 years old, we obtained the written informed consent from patient's parent.

Spinal teratoma was first described by Virchow and Gowers in 1863 [6]. Most cases of spinal teratoma are diagnosed in the first two decades of life, Nsir et al. [7] noted that so far, few cases of conus medullaris teratoma are published in the literature and most of them were adults. According to the previous studies about one-third of cases accompanied by total resection [7]. Işik et al. [8] reported a case of intramedullary teratoma of conus medullaris in 2008 and stated that they could resect the tumor totally with no neurological symptoms. Oktay et al. [9] presented a 12-year-old male patient with conus medullaris teratoma with 95% tumor resection. In further follow up examinations, all symptoms were faded away. Moreover, the authors declared that intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring can help maximum resection of the tumor. Hejazi and Witzmann [10] reported total resection of conus medullaris teratoma in two adult patients. The authors mentioned that intramedullary teratoma of conus medullaris is very rare and should be considered as a differential diagnosis of cauda equina tumors. They suggested that surgical resection should be done before onset of neurological deficits. Most cases of spinal teratoma in adults are found in thoracolumbar region and specially conus medullaris area [11].

The pathogenesis of spinal teratoma is not exactly known, but there are two theories. One theory has hypothesized that these tumors are originated from primordial germ cells that has migrated incorrectly during embryogenesis in dysraphism. Another theory suggests although germinomas are originated from germ cells, other non-germinoma germ cell tumors such as teratomas occur because of misfolding and misplacement of embryonic cells into the lateral mesoderm [12].

In addition to congenital malformations in adults with teratoma, evidence of trauma or surgery such as lumbar punctures has been observed in these patients [13]. Iatrogenic cysts may occur because of entering dermal and epidermal tissues during closure of myelomeningoceles or entering epithelium during spinal epidural injections [14].

Diagnosis of teratoma is based on histopathologic findings and the specimen should contain three germinal layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm); however, the existence of only two layers does not rule out the diagnosis [13].

The tumor has three pathologic subtypes: mature, immature, and malignant. The mature type is the most common form [15]. Mature and immature types are considered benign specially if treated immediately. Mature teratomas consist of differentiated components such as chondrocytes, squamous epithelial cells, endocrine tissues, mucosal cells, and neural elements. Immature types are more aggressive and contain primitive, undifferentiated, and embryonic tissues. Malignant tumors-as the name implies-contain some components of malignant germ cells and are originated from yolk sac or endoderaml sinuses. The malignant forms are associated with high levels of serum alpha fetoprotein and poor prognosis [61116].

Teratoma's association with spinal malformations such as spina bifida, partial sacral agenesis, hemivertebrae, myelomeningocele, tethered cord and diastematomyelia has been reported in literature [11]. Since most cases of spinal teratomas are associated with anomalies such as split cord and dysraphism, these lesions may be non-neoplastic and occur due to dysembryogenic mechanisms [1617].

Spinal teratomas may be extra-dural, intra-dural or intramedullary. Intramedullary types are rare cases and they tend to occur in thoracolumbar area [8]. Moreover intradural, extramedullary teratoma cases are more common in childhood [11]. Oktay et al. [9] presented a 12-year-old male patient with conus medullaris teratoma with 95% tumor resection. In further follow up examinations, all symptoms were faded away. Moreover, the authors declared that intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring can help maximum resection of the tumor.

In these patients the most common symptoms are weakness of extremities (paresis), sensory alterations and abnormalities in DTRs which depend on the location of the tumor [6].

MRI is the gold-standard diagnostic method for spinal teratoma, however other imaging modalities like plain X-ray and CT scans can be used as well. Abnormalities in these modalities are bone and vertebral anomalies, erosions and increased interpeduncular space [6]. MRI shows teratoma as a heterogeneous mass containing solid and cystic components and usually fat tissue is also found in the lesion like our case which is helpful for preoperative diagnosis [18]. Differential diagnosis of spinal teratomas is ependymoma, astrocytoma, and complicated neurenteric cysts [19].

As the natural history of these tumors is unknown, the treatment method of choice in children with teratoma is complete resection of tumor [2021]. Total resection of the lesion should be performed to prevent recurrence, but if total resection may accompany neurological damages and deficits, resection must be stopped [6]. Extensive laminectomy in 30–80% of patients leads to spinal cord instability; therefore simultaneous laminoplasty is recommended [22].

The recurrence rate of tumor depends on histopathologic type, as we can see symptomatic recurrence in mature teratomas even in cases with subtotal resection is rare. Recurrence rate is estimated about 10% in previous studies and it was reported mostly in immature and malignant forms [8]. As the tumor is slow growing, the patients need long-lasting follow ups and serial imaging for many years [2324].

Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended for teratomas containing malignant components, but there is no evidence of the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in these patients [92325]. In very rare cases of immature types with evidence of malignancy, postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy may alter the aggressive behavior of this tumors and lead to complete and permanent cure [1026]. Also the age of the patient and surgical approaches may influence the clinical outcomes [27].

References

1. Barksdale EM Jr, Obokhare I. Teratomas in infants and children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009; 21:344–349. PMID: 19417664.

2. Billmire DF, Grosfeld JL. Teratomas in childhood: analysis of 142 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1986; 21:548–551. PMID: 2425069.

3. Gu W, Shang H, Jin X, Xie J, Zhao W. Intradural lumbar mature teratoma with neuronal and glial tissue component in an adult. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010; 50:1112–1115. PMID: 21206190.

4. Nonomura Y, Miyamoto K, Wada E, et al. Intramedullary teratoma of the spine: report of two adult cases. Spinal Cord. 2002; 40:40–43. PMID: 11821970.

5. Fernández-Cornejo VJ, Martínez-Pérez M, Martínez-Lage JF, Poza M, Polo-García LA. Cystic mature teratoma of the filum terminale in an adult. Case report and review of the literature. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2004; 15:290–293. PMID: 15239016.

6. Agay AK, Garg S, Hedaoo K. Spinal intradural extramedullary mature cystic teratoma in young adult: a rare tumor with review of literature. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016; 4:5481–5483.

7. Nsir AB, Hammouda KB, Said IB, Kassar AZ, Kchir N, Jemel H. Spinal intradural mature teratoma in an elderly patient. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2015; 1:106–110.

8. Işik N, Balak N, Silav G, Elmaci I. Pediatric intramedullary teratomas. Neuropediatrics. 2008; 39:196–199. PMID: 19165706.

9. Oktay K, Cetinalp NE, Ozsoy KM, Olguner SK, Sarac ME, Vural SB. Intramedullary mature teratoma of the conus medullaris. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016; 7:305–307. PMID: 27114670.

10. Hejazi N, Witzmann A. Spinal intramedullary teratoma with exophytic components: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2003; 26:113–116. PMID: 12962297.

11. Ak H, Ulu MO, Sar M, Albayram S, Aydin S, Uzan M. Adult intramedullary mature teratoma of the spinal cord: review of the literature illustrated with an unusual example. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006; 148:663–669. PMID: 16523223.

12. Echevarría ME, Fangusaro J, Goldman S. Pediatric central nervous system germ cell tumors: a review. Oncologist. 2008; 13:690–699. PMID: 18586924.

13. Stevens QE, Kattner KA, Chen YH, Rahman MA. Intradural extramedullary mature cystic teratoma: not only a childhood disease. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006; 19:213–216. PMID: 16770222.

14. Kudo N, Hasegawa K, Ogose A, et al. Malignant transformation of a lumbar intradural dermoid cyst. J Orthop Sci. 2007; 12:300–302. PMID: 17530384.

15. Tihitena N, Mesay A. Case report: a rare presentation of spinal teratoma in neonates: two cases from Ethiopia. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2017; 24:5–7.

16. Koen JL, McLendon RE, George TM. Intradural spinal teratoma: evidence for a dysembryogenic origin. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 1998; 89:844–851. PMID: 9817426.

17. Mut M, Shaffrey ME, Bourne TD, Jagannathan J, Shaffrey CI. Unusual presentation of an adult intramedullary spinal teratoma with diplomyelia. Surg Neurol. 2007; 67:190–194. PMID: 17254890.

18. Monajati A, Spitzer RM, Wiley JL, Heggeness L. MR imaging of a spinal teratoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986; 10:307–310. PMID: 3950158.

19. Rauzzino MJ, Tubbs RS, Alexander E 3rd, Grabb PA, Oakes WJ. Spinal neurenteric cysts and their relation to more common aspects of occult spinal dysraphism. Neurosurg Focus. 2001; 10:e2.

20. Tapper D, Lack EE. Teratomas in infancy and childhood. A 54-year experience at the Children's Hospital Medical Center. Ann Surg. 1983; 198:398–410. PMID: 6684416.

21. Barahona EA, Olvera JN, Liquidano ME, et al. A special case of intramedullary teratoma in an adult. Literature review. Rev Med Hosp Gen Mex. 2018; 81:237–242.

22. Poeze M, Herpers MJ, Tjandra B, Freling G, Beuls EA. Intramedullary spinal teratoma presenting with urinary retention: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1999; 45:379–385. PMID: 10449085.

23. Allsopp G, Sgouros S, Barber P, Walsh AR. Spinal teratoma: is there a place for adjuvant treatment? Two cases and a review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2000; 14:482–488. PMID: 11198778.

24. Pandey S, Sharma V, Shinde N, Ghosh A. Spinal intradural extramedullary mature cystic teratoma in an adult: a rare tumor with review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 2015; 10:133–137. PMID: 26396595.

25. Li Y, Yang B, Song L, Yan D. Mature teratoma of the spinal cord in adults: an unusual case. Oncol Lett. 2013; 6:942–946. PMID: 24137441.

26. Yoshioka F, Shimokawa S, Masuoka J, et al. Extensive spinal epidural immature teratoma in an infant: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2018; 22:411–415. PMID: 29979131.

27. Güvenç BH, Etus V, Muezzinoglu B. Lumbar teratoma presenting intradural and extramedullary extension in a neonate. Spine J. 2006; 6:90–93. PMID: 16413454.

Fig. 1

Preoperative sagittal T1-weighted (T1W) (A), sagittal T2-weighted (B), sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) (C), and axial T2-weighted (D and E) MRI images of the conus medullaris mass show a well-defined intradural intramedullary mass with cystic components. Note the hypersignal area in T1W sagittal image that loses signal in STIR image, consistent with fat.

Fig. 3

Postoperative sagittal T1-weighted (A), sagittal T2-weighted (B), and axial T2-weighted (C) MRI images in the same patient show near total resection of conus medullaris mass. Note the near total resection of conus medullaris mass.

Fig. 4

Histopathologic appearance. A, B and C with H&E staining show mature neuroglial and meningothelial tissue with a central cavity lined by squamous epithelium, producing lamellar keratin and mucous gland within the wall (magnification ×100). Fibro connective and adipose tissue with a cyst lined by respiratory epithelium are seen. D and E with H&E staining show salivary type mucus glands (D, magnification ×100) and ciliated epithelium (E, magnification ×400). These findings are in favor of mature teratoma.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download