Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to a group of chronic inflammatory diseases—which include CD and UC—that predominantly affect the gastrointestinal tract. The incidence of IBD was reported to be 8–14 per 100,000 persons in the West.1 The crude annual incidence of IBD was revealed to be 1.96–5.3 per 100,000 persons in Asia.2 The ratio of UC to CD was 2.0 in Asia. IBD is increasing in both incidence and prevalence in Asian area.3 IBD is associated with autoimmune disease and increased risk of thromboembolic events. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. VTE is associated with significant risk of mortality, chronic complications, and recurrence. The 1-year case-fatality rate has been reported to be 22%–29% in Western countries.45 One-third of patients who survived deep vein thrombosis would experience long-term post-thrombotic syndrome. Symptoms include pain, persistent swelling, and recurrent ulcers of the affected extremity. Patients with pulmonary embolism may develop chronic pulmonary hypertension. In this review, we would discuss the difference in VTE incidence between Asian and Western countries and evaluate whether Asian patients with IBD should receive routine thromboprophylaxis.

The incidence of VTE in Western countries has been reported to range from 0.73 to 1.82 per 1,000 persons.67 The VTE incidence has been reported to be 0.21–0.57 per 1,000 persons in Asia.89 In North America, VTE was most common in African-Americans, with an incidence of 1.38–1.41 cases per 1,000 individuals per year, followed by Europeans (1.03–1.49 cases per 1,000 individuals) and Hispanic populations. The incidence of VTE in Asian-ancestry populations (0.21–0.29 cases per 1,000 individuals) was less than one-fifth the incidence of African-Americans.9

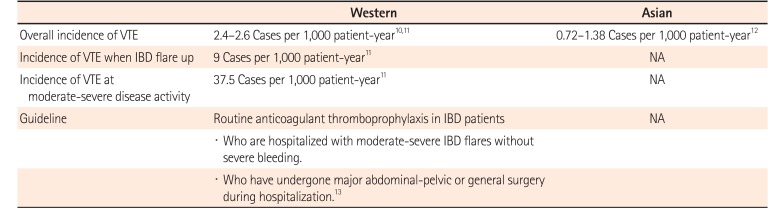

In Western countries, patients with IBD have a nearly 1.5- to 4.0-fold higher risk of VTE when compared with the general population.10 The overall incidence of VTE in patients with IBD has been reported as 2.4–2.6 cases per 1,000 patients per year,1011 and the incidence was revealed to increase to 9 cases per 1,000 patients per year when disease flare-up in the U.K. IBD population.11 The incidence of VTE among patients with IBD in Taiwan was reported to be 1.38 per 1,000 patients per year in a nationwide study.12 As moderate-severe disease activity and hospitalization for IBD flares both increase the risk of VTE,11 routine anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis is recommended in patients hospitalized with moderate-severe IBD flares and in patients who have undergone major abdominal-pelvic surgery during hospitalization (Table 1).10111213 For the treatment of VTE, a minimum of 3 months of anticoagulant therapy for IBD patients with a symptomatic deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or splanchnic vein thrombosis is strong recommended.13 Currently, there is no evidence of which anticoagulants is the most effective, treatment choice is depended on consistency and quality of anticoagulation, ease of use, monitoring needs, side-effects and cost.8 However, these guidelines are based on data gathered from Western populations. In general, the incidence of VTE in Asian populations is lower than that in Western populations. Routine thromboprophylaxis is infrequently used in Asian patients with IBD.

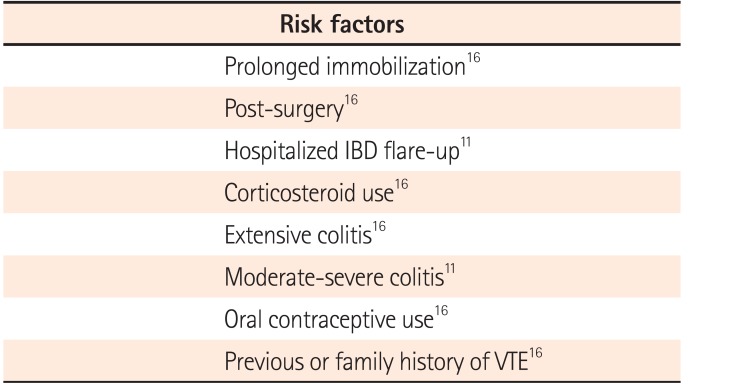

The pathogenesis of VTE in patients with IBD is multifactorial, involving both genetic and acquired factors. The hypercoagulation status can be caused by loss of anticoagulants or thrombophilia. Thrombophilia refers to familial or acquired hemostatic disorders that increases the risk of thrombosis. Loss of anticoagulants includes deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C, and protein S. Thrombophilia can be caused by factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210A mutations, and elevation of procoagulant factors, such as von Willebrand factor or factors V, VII, VIII, IX and XI. The variation among ethnicities in incidence of VTE is attributed to genetic disparity. Chinese patients have lower levels of thrombosis markers, including factor VIII, D-dimer, plasmin-antiplasmin, and von Willebrand factor, than Caucasian or Hispanic patients. Lower incidence of factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A mutation was also reported in Asian populations.14 Obesity is an endogenous risk factor for VTE. Increasing BMI was associated with a rising risk of VTE. Although the prevalence of obesity has increased in Asia with economic development, the adult prevalence of metabolic syndrome remains higher in the United States (34.7%) than in Malaysia (27.5%) and China (7.3%).15 Other risk factors include prolonged immobilization, surgery, hospitalization for IBD flare-up, patient or family history of VTE, corticosteroid and oral contraceptive use (Table 2).1116

Currently, pharmacological thromboprophylaxis is not standard treatment for patients with IBD in Asian countries. A multinational, web-based survey showed ≤24% of clinicians provide adequate prophylaxis for VTE in Asia.17 Our multinational collaborative study enrolled 2,562 hospitalized IBD patients from Korea, Japan and Taiwan showed the average incidence of VTE was 0.72–1.38 per 1,000 persons per year in East-Asian patients with IBD.18 In Western patients with IBD, the overall incidence of VTE has been determined to be 2.4–2.6 per 1,000 persons per year.1011 Because of the relatively low incidence of VTE, the benefits of pharmacological prophylaxis are expected to be small in Asian patients with IBD. These results also support our current practice of not treating with prophylaxis for VTE. However, we did observe a 2-fold increase in VTE risk in patients with IBD when compared with the general population, and we recommend close monitoring of symptoms in patients with IBD with high risk factors for VTE.

The incidence of VTE is lower in Asia for both general and IBD populations than in Western countries. Currently, VTE prevention is not standard for Asian patients with IBD, and routine pharmacological prophylaxis is not recommended. However, patients with additional risk factors such as previous surgery, hospitalization, and moderate-severe disease must be considered for routine thromboprophylaxis. Guidelines for VTE prophylaxis in Asian patients with IBD should be established.

Notes

References

1. Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011; 140:1785–1794. PMID: 21530745.

2. Vegh Z, Kurti Z, Lakatos PL. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases from west to east. J Dig Dis. 2017; 18:92–98. PMID: 28102560.

3. Thia KT, Loftus EV Jr, Sandborn WJ, Yang SK. An update on the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008; 103:3167–3182. PMID: 19086963.

4. Burwen DR, Wu C, Cirillo D, et al. Venous thromboembolism incidence, recurrence, and mortality based on Women's Health Initiative data and Medicare claims. Thromb Res. 2017; 150:78–85. PMID: 28063368.

5. Arshad N, Bjøri E, Hindberg K, Isaksen T, Hansen JB, Braekkan SK. Recurrence and mortality after first venous thromboembolism in a large population-based cohort. J Thromb Haemost. 2017; 15:295–303. PMID: 27943560.

6. Spencer FA, Emery C, Joffe SW, et al. Incidence rates, clinical profile, and outcomes of patients with venous thromboembolism: the Worcester VTE study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009; 28:401–409. PMID: 19629642.

7. Huang W, Goldberg RJ, Anderson FA, Kiefe CI, Spencer FA. Secular trends in occurrence of acute venous thromboembolism: the Worcester VTE study (1985-2009). Am J Med. 2014; 127:829–839. PMID: 24813864.

8. Cohen A, Chiu KM, Park K, et al. Managing venous thromboembolism in Asia: winds of change in the era of new oral anticoagulants. Thromb Res. 2012; 130:291–301. PMID: 22766512.

9. Huang SS, Liu Y, Jing ZC, Wang XJ, Mao YM. Common genetic risk factors of venous thromboembolism in Western and Asian populations. Genet Mol Res. 2016; 15:15017644. DOI: 10.4238/gmr.15017644. PMID: 26985940.

10. Kappelman MD, Horvath-Puho E, Sandler RS, et al. Thromboembolic risk among Danish children and adults with inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based nationwide study. Gut. 2011; 60:937–943. PMID: 21339206.

11. Grainge MJ, West J, Card TR. Venous thromboembolism during active disease and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010; 375:657–663. PMID: 20149425.

12. Chung WS, Lin CL, Hsu WH, Kao CH. Inflammatory bowel disease increases the risks of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the hospitalized patients: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Res. 2015; 135:492–496. PMID: 25596768.

13. Nguyen GC, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, et al. Consensus statements on the risk, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel disease: Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2014; 146:835–848. PMID: 24462530.

14. Jun ZJ, Ping T, Lei Y, Li L, Ming SY, Jing W. Prevalence of factor V Leiden and prothrombin G20210A mutations in Chinese patients with deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Clin Lab Haematol. 2006; 28:111–116. PMID: 16630215.

15. DeBoer MD, Gurka MJ. Clinical utility of metabolic syndrome severity scores: considerations for practitioners. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2017; 10:65–72. PMID: 28255250.

16. Zezos P, Kouklakis G, Saibil F. Inflammatory bowel disease and thromboembolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:13863–13878. PMID: 25320522.

17. Song HK, Lee KM, Jung SA, et al. Quality of care in inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: the results of a multinational web-based survey in the 2(nd) Asian Organization of Crohn's and Colitis (AOCC) meeting in Seoul. Intest Res. 2016; 14:240–247. PMID: 27433146.

18. Weng MT, Matsuoka K, Tung CC, et al. Incidence and risk factor analysis of thromboembolic events in Asian patients with inflammatory bowel disease, a multinational collaborative study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018; (in press).

Table 1

Incidence and Guideline of VTE in IBD Patients

| Western | Asian | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall incidence of VTE | 2.4–2.6 Cases per 1,000 patient-year1011 | 0.72–1.38 Cases per 1,000 patient-year12 |

| Incidence of VTE when IBD flare up | 9 Cases per 1,000 patient-year11 | NA |

| Incidence of VTE at moderate-severe disease activity | 37.5 Cases per 1,000 patient-year11 | NA |

| Guideline | Routine anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis in IBD patients | NA |

| · Who are hospitalized with moderate-severe IBD flares without severe bleeding. | ||

| · Who have undergone major abdominal-pelvic or general surgery during hospitalization.13 |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download