RESULTS

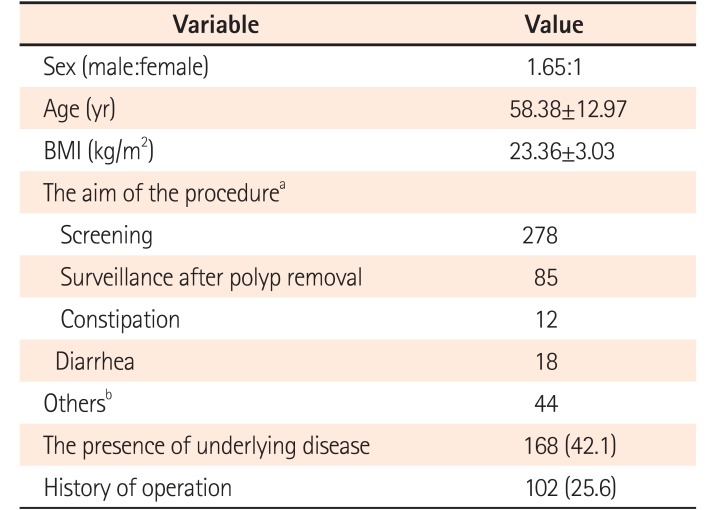

A total of 399 consecutive patients were enrolled. Mean patient age was 58.38±12.97 years and 60.6% were male. Their mean BMI was 23.36±3.03 kg/m

2. Indications for CFS were 69.7% screening, 21.3% surveillance after polyp removal, and 3.0% constipation. Just below half (42.1%) of the patients in our study revealed having at least one comorbidity such as hypertension or cerebrovascular disease, and one-quarter (25.6%) of them had a history of abdominal surgery (

Table 1). The last stool status before CFS was clear liquid in 387 patients (96.9%).

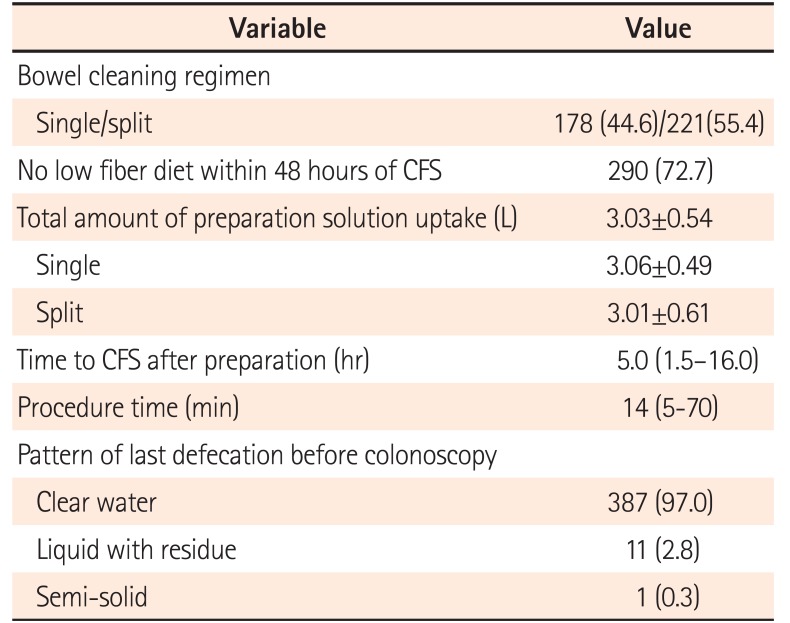

Just over half (n=221, 55.4%) of our patients followed the split protocol, while the others (n=178, 44.6%) followed the single protocol. Regarding colon preparation quality, 104 of colonoscopies (26.1%) were judged as “excellent,” 183 (45.8%) as “good,” 99 (24.8%) as “fair,” 12 (3.0%) as “poor”, and 1 (0.1%) as “inadequate.” Overall, 287 patients (71.9%) achieved adequate bowel preparation and 112 patients (28.1%) achieved inadequate bowel preparation. Overall, the median time between the last dose of the bowel preparation agent and the start of CFS was 5.0 hours (1.5–16.0 hours); that in the A group was 5.0 hours (1.5–16.0 hours); and that in the I group was 5 hours (2–23 hours) (

P=0.190). The overall median procedure time was 14 minutes (5–70 minutes); that in the A group was 15 minutes (5–60 minutes); and that in the I group was 17.5 minutes (5–70 minutes) (

P=0.950) (

Table 2).

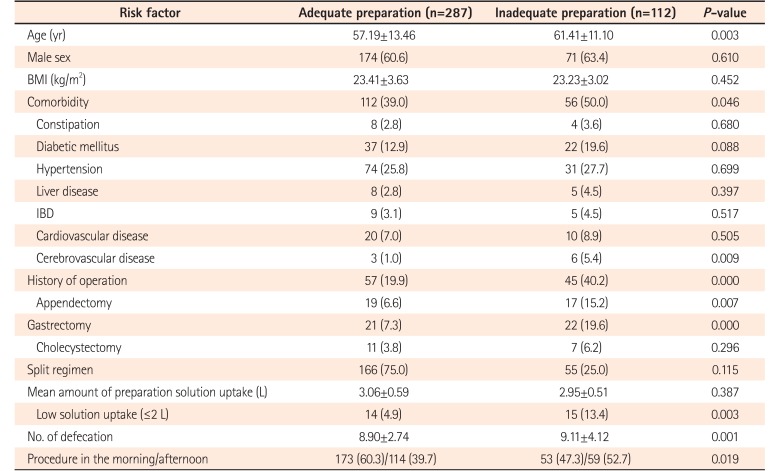

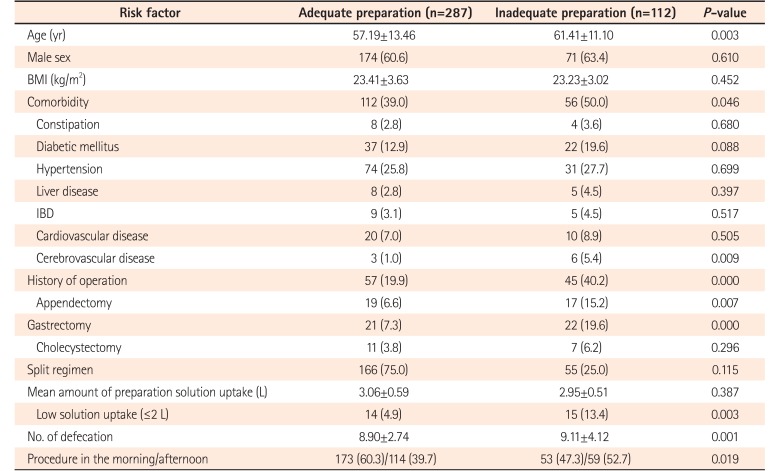

CFS was performed in the afternoon in 39.7% (n=114) of patients in the A group versus 52.7% (n=59) of patients in the I group (

P=0.02). Patients who underwent abdominal surgery were more in I group (19.9% vs. 40.2%,

P<0.01). A total preparation solution uptake of <2 L was reported by 4.9% of patients (n=14) in the A group versus 13.4% of patients (n=15) in the I group (

P<0.01) (

Table 3).

Table 3

Clinical Comparison of Patients by Adequate or Inadequate Bowel Preparation Findings

|

Risk factor |

Adequate preparation (n=287) |

Inadequate preparation (n=112) |

P-value |

|

Age (yr) |

57.19±13.46 |

61.41±11.10 |

0.003 |

|

Male sex |

174 (60.6) |

71 (63.4) |

0.610 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

23.41±3.63 |

23.23±3.02 |

0.452 |

|

Comorbidity |

112 (39.0) |

56 (50.0) |

0.046 |

|

Constipation |

8 (2.8) |

4 (3.6) |

0.680 |

|

Diabetic mellitus |

37 (12.9) |

22 (19.6) |

0.088 |

|

Hypertension |

74 (25.8) |

31 (27.7) |

0.699 |

|

Liver disease |

8 (2.8) |

5 (4.5) |

0.397 |

|

IBD |

9 (3.1) |

5 (4.5) |

0.517 |

|

Cardiovascular disease |

20 (7.0) |

10 (8.9) |

0.505 |

|

Cerebrovascular disease |

3 (1.0) |

6 (5.4) |

0.009 |

|

History of operation |

57 (19.9) |

45 (40.2) |

0.000 |

|

Appendectomy |

19 (6.6) |

17 (15.2) |

0.007 |

|

Gastrectomy |

21 (7.3) |

22 (19.6) |

0.000 |

|

Cholecystectomy |

11 (3.8) |

7 (6.2) |

0.296 |

|

Split regimen |

166 (75.0) |

55 (25.0) |

0.115 |

|

Mean amount of preparation solution uptake (L) |

3.06±0.59 |

2.95±0.51 |

0.387 |

|

Low solution uptake (≤2 L) |

14 (4.9) |

15 (13.4) |

0.003 |

|

No. of defecation |

8.90±2.74 |

9.11±4.12 |

0.001 |

|

Procedure in the morning/afternoon |

173 (60.3)/114 (39.7) |

53 (47.3)/59 (52.7) |

0.019 |

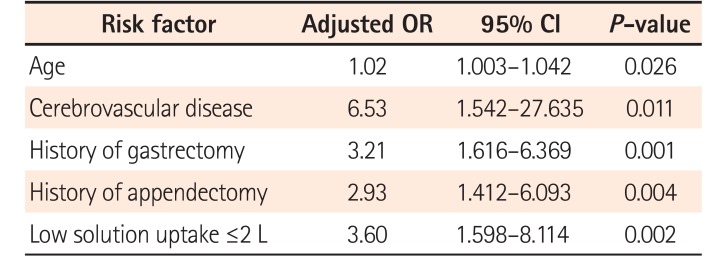

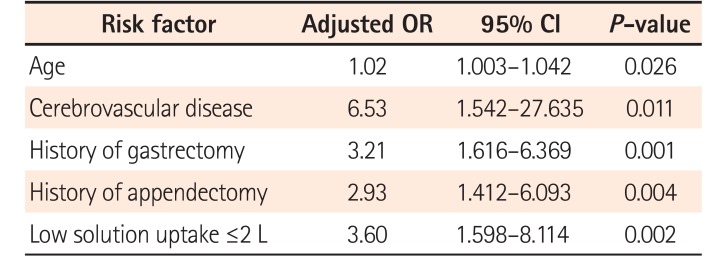

On multivariate analysis, elderly age (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.003–1.042;

P=0.03), history of cerebrovascular disease (OR, 6.53; 95% CI, 1.542–27.635;

P<0.01), history of gastrectomy (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.616–6.369;

P<0.01) or appendectomy (OR, 2.93; 95% CI, 1.412–6.093;

P<0.01), and a total intake of the preparation solution of <2 L (OR, 3.60; 95% CI, 1.598–8.114;

P<0.01)were the independent predictors of inadequate bowel preparation (

Table 4).

Table 4

Risk Factors of Poor Bowel Preparation by Multivariate Analysis

|

Risk factor |

Adjusted OR |

95% CI |

P-value |

|

Age |

1.02 |

1.003–1.042 |

0.026 |

|

Cerebrovascular disease |

6.53 |

1.542–27.635 |

0.011 |

|

History of gastrectomy |

3.21 |

1.616–6.369 |

0.001 |

|

History of appendectomy |

2.93 |

1.412–6.093 |

0.004 |

|

Low solution uptake ≤2 L |

3.60 |

1.598–8.114 |

0.002 |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Inadequate bowel preparation results in a reduced adenoma detection rate and is associated with interval CRC.

6 According to the ASGE and AGA suggestions of CFS quality indicators, adequate preparation should be >98%.

2 To accomplish this target rate, it is very important to identify patients with risk factors of poor bowel preparation to enable improvement. Accordingly, we aimed to investigate the frequency of inadequate bowel preparation in real clinical practice and the associated risk factors that need to be improved.

Previous studies reported that the inadequate bowel preparation rate was 21% to 28%, similar to our findings. Our results showed the status of actual clinical practice, and considering the suggested proportion of adequate bowel preparation in quality indicator of CFS,

2 further stress the need for greater attention on improving bowel preparation status.

Our study findings suggested that elderly age, history of cerebrovascular disease, history of gastrectomy or appendectomy, and a total preparation solution uptake <2 L are significant predictors of inadequate bowel preparation. These results were similar to those of several previous studies.

1789

As life expectancy increases, the indication of CFS in elderly patients also increases.

10 One study showed that the incidence of inadequate preparation in old age is high.

11 In the current study, increased age was an independent risk factor for inadequate bowel preparation, which could be associated with delayed gastrointestinal motility, poor understanding of preparation instructions, high constipation rate, comorbid diseases such as diabetes, and a higher incidence of a history of abdominal surgery.

Chung et al.

1 reported that a history of colectomy, hysterectomy, or appendectomy was a risk factor of inadequate bowel preparation. However, our data did not reveal any difference in bowel preparation status by history of hysterectomy, likely because too few patients had a history of hysterectomy (n=6). We found that a history of other intra-abdominal surgeries such as appendectomy and gastrectomy were independent risk factors of inadequate bowel preparation. These findings suggest that any kind of intra-abdominal surgery could affect bowel preparation status due to altered bowel motility and postoperative adhesions.

Failure to ingest sufficient preparation solution is also a cause of inadequate bowel preparation.

12131415 Although several kinds of preparation solutions have become available in an effort to improve compliance, patient satisfaction is limited. Common reasons for noncompliance include patient discomfort and intolerance to ingesting a large solution volume.

16 In our study, 29 patients (7.3%) ingested an inadequate preparation solution volume (<2 L). Although Chiu et al.

17 reported that the ingestion of 2 L of bowel preparation solution was sufficient to achieve an adequate bowel preparation, if ingested according to the preparation time protocol, doing so in actual practice is not so easy for patients.

In our study, a history of cerebrovascular disease was an independent predictor of inadequate bowel preparation. The possible causes for this include an increased incidence of bed-ridden status, a high frequency of constipation, delayed gastrointestinal motility, and medications that could affect the bowel motility.

91819

A previous study suggested other factors such as medical problems that influence bowel motility including liver cirrhosis, diabetes, chronic constipation, multiple medications, obesity, and hospitalization as predictors of inadequate bowel preparation.

1 However, the current study did not show any significant results regarding these factors, possibly due to inadequate numbers of patients with these comorbidities.

In a recent study, the split regimen was reportedly more effective than the single regimen for achieving dose in bowel preparation;

2021 however, our study revealed no significant intergroup difference. This may be due to 15 of 221 patients (6.9%) who received a split dose versus 3 of 178 patients (1.7%) who received the single dose vomiting during the bowel preparation process, representing a statistically significant difference (

P=0.01) and possibly offsetting the benefit of the split dose. In addition, our study intended to reveal the actual practice, in which patient characteristics could be heterogeneous and preparation regimen may be of no significance.

In our study, patients who underwent CFS in the afternoon had a higher incidence of inadequate bowel preparation (A group, 114 [39.7%]; I group, 59 [52.7%]; P=0.02) as well as a higher incidence of being prescribed the single bowel preparation protocol. However, inadequate bowel preparation was not significantly associated with single bowel preparation protocol. Inadequate bowel preparations were more frequent in the afternoon patients because these patients had a higher incidence of a history of cerebrovascular disease or intra-abdominal surgery (morning patients, 47 [20.8%]; afternoon patients, 63 [36.4%]). These results suggest that other factors as well as compliance are more influential than regimen method.

In our study, 72.7% of patients ingested a low fiber diet for the 48 hours prior to CFS, while 92% ingested a total uptake preparation solution volume >2 L. A low understanding of the instructions and poor awareness of the results of inadequate bowel preparation could result in patient non-compliance. Nguyen and Wieland

22 reported that a poor understanding of the instructions is a significant factor of poor bowel preparation. Education regarding bowel preparation could effectively improve bowel preparation status.

232425 Lee et al.

26 also reported that bowel preparation protocol reinforcement education by telephone or text message increased the adequate bowel preparation rate. Using these methods, especially with elderly patients, will help increase the adequate bowel preparation rate.

Our study has several limitations. First, the bowel preparation status assessments were performed by 3 endoscopists, which may introduce inter-observer variation. To reduce it, the endoscopists referred to a photographic example of bowel preparation conditions at every examination prior to scoring. Second, because the data of total solution intake, number of bowel movements, time to CFS after preparation, and pattern of last defecation before CFS depended on patient memory, recall bias could be a factor. Third, to see the actual clinical outcomes, patients who were excluded from other studies (those with a history of surgery or other factors) were included in our study, which could create a confounding factor.

Nevertheless, in Asia, our study included relatively large numbers of patients who were subjected to a standard CFS protocol. As such, it can reflect the degree of bowel preparation in actual clinical practice. Our results may help clinicians identify patients at high risk of inadequate bowel preparation.

In conclusion, 28.1% of our patients had inadequate bowel preparation, the risk factors of which were elderly age, a history of intra-abdominal surgery such as appendectomy or gastrectomy, a history of cerebrovascular disease, and inadequate preparation solution consumption(<2 L). Our findings suggest that special care and an individualized approach are required for patients with risk factors of inadequate bowel preparation, including a comprehensive education program about preparation and the encouragement of an appropriate diet and ambulation during preparation for CFS.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download