Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, is a chronic, debilitating, and expensive condition affecting millions of people globally. There is significant variation in the quality of care for patients with IBD across North America, Europe, and Asia; this variation suggests poor quality of care due to overuse, underuse, or misuse of health services and disparity of outcomes. Several initiatives have been developed to reduce variation in care delivery and improve processes of care, patient outcomes, and reduced healthcare costs. These initiatives include the development of quality indicator sets to standardize care across organizations, and learning health systems to enable data sharing between doctors and patients, and sharing of best practices among providers. These programs have been variably successful in improving patient outcomes and reducing healthcare utilization. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the long-term impact and applicability of these efforts in different geographic areas around the world, as regional variations in patient populations, societal preferences, and costs should inform local quality improvement efforts.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including CD and UC are chronic, debilitating, and expensive conditions.1 There are many aspects of IBD care that make it apt for quality improvement (QI), including the significant variation in how care is delivered,234 the prevalence of potentially preventable disease- and medication-associated complications56 and a significant direct and indirect individual and societal cost burden of illness.1 IBD care is expensive and complex–patients commonly require multidisciplinary care, biologic medications, inpatient care, and surgeries.7 Several QI initiatives have been developed to address these issues, although in different ways. Some initiatives are aimed at defining quality of care in IBD, such as the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) IBD performance measures,8 the Crohn's & Colitis Foundation (CCFA) process and outcome measures,9 and the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) IBD standard set. Other initiatives are focusing on the development of learning health systems including ImproveCareNow and IBD Qorus; these are virtual platforms and networked practices which allow for sharing of data and best practices, along with QI training for IBD centers and practices, predominantly in the United States. These programs have also developed standardized care pathways to provide evidenced-based algorithms to improve focused aspects of clinical care.

While many aspects of QI in IBD are equally relevant across the globe such as the need to avoid steroids and disease complications, there may be important regional differences with respect to the prevalence of distinct disease phenotypes, genetic drivers of disease manifestations and response to therapy, prevalence of potential “mimickers” of the disease such as tuberculosis that may warrant specific approaches to treatment, epidemiology of environmental triggers such as prevalence of smoking, availability of specific treatment options and diagnostic tests, societal preferences, and costs. These differences highlight the need for regionally relevant QI initiatives and critical evaluation of the available quality measures and care pathways to ensure that they are appropriate to specific populations and healthcare environments.

Quality indicators, or quality measures, are used to objectively assess the quality of care by determining whether certain evidenced-based, expert-recommended, or patient-centric aspects of care are being followed. Quality indicators are intended to be “specific, measurable elements of care for which there is evidence of consensus that can be used to assess the quality care provided and hence change it,” and offer the potential to “define basic, minimally acceptable care and help distinguish good quality from bad.”101112 These measures have typically followed the Donabedian13 model, and applied to the structure, process, or outcomes of care. Structure measures pertain to the overall availability of healthcare resources like staffing, access to specialists, and medication availability. Process measures pertain to the steps (or “processes”) that lead to a particular outcome measure such as timely diagnosis, early treatment, appropriateness of medication use, and health care maintenance such as vaccination and cancer screening. Outcome measures are high-level clinical outcomes which matter most to patients and are the most important yet most difficult to measure. Outcome measures might include mortality, days hospitalized, number of emergency room visits, and proportion of patients in remission. In addition to these 3 categories of quality measures, “balance” measures are commonly used to ensure that improvement in one area is not degrading performance in another area. For example, if hospital length of stay is an outcome measure, the balance measure could be patient satisfaction to ensure patients do not feel rushed out of the hospital, or readmission rates to ensure patients are not discharged before medically ready. Patient satisfaction measures represent an entirely different aspect of quality measurement focused on the patient, which have become increasingly important and relevant to hospital payments in the United States.

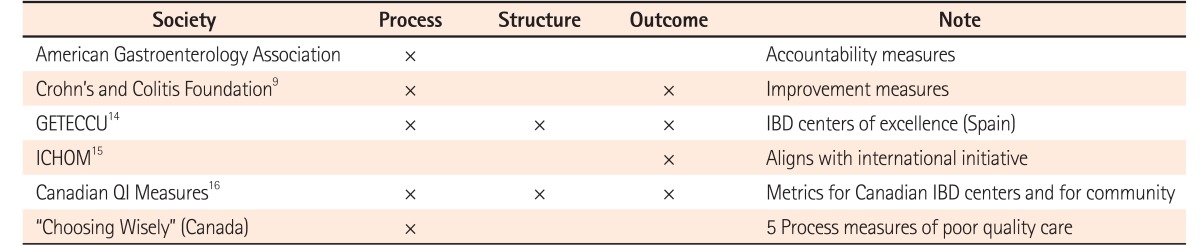

Several organizations have developed quality measures for IBD (Table 1).9141516 The AGA has developed process measures for IBD which have been used by the federal health insurance program in the United States, Medicare, to provide financial incentives (or avoid financial penalties) for gastroenterologists when caring for patients with IBD.17 However, these measures are limited in scope and primarily used for accountability and reporting for financial incentives, rather than for QI purposes. In Asia, there is varied delivery and awareness of some of the AGA measures as determined in a recent multinational physician survey; reasons cited for this variation included cost, time involved in performing the recommended intervention, and variable perception of the importance or relevance of a particular measure to the clinical status of the patient.18

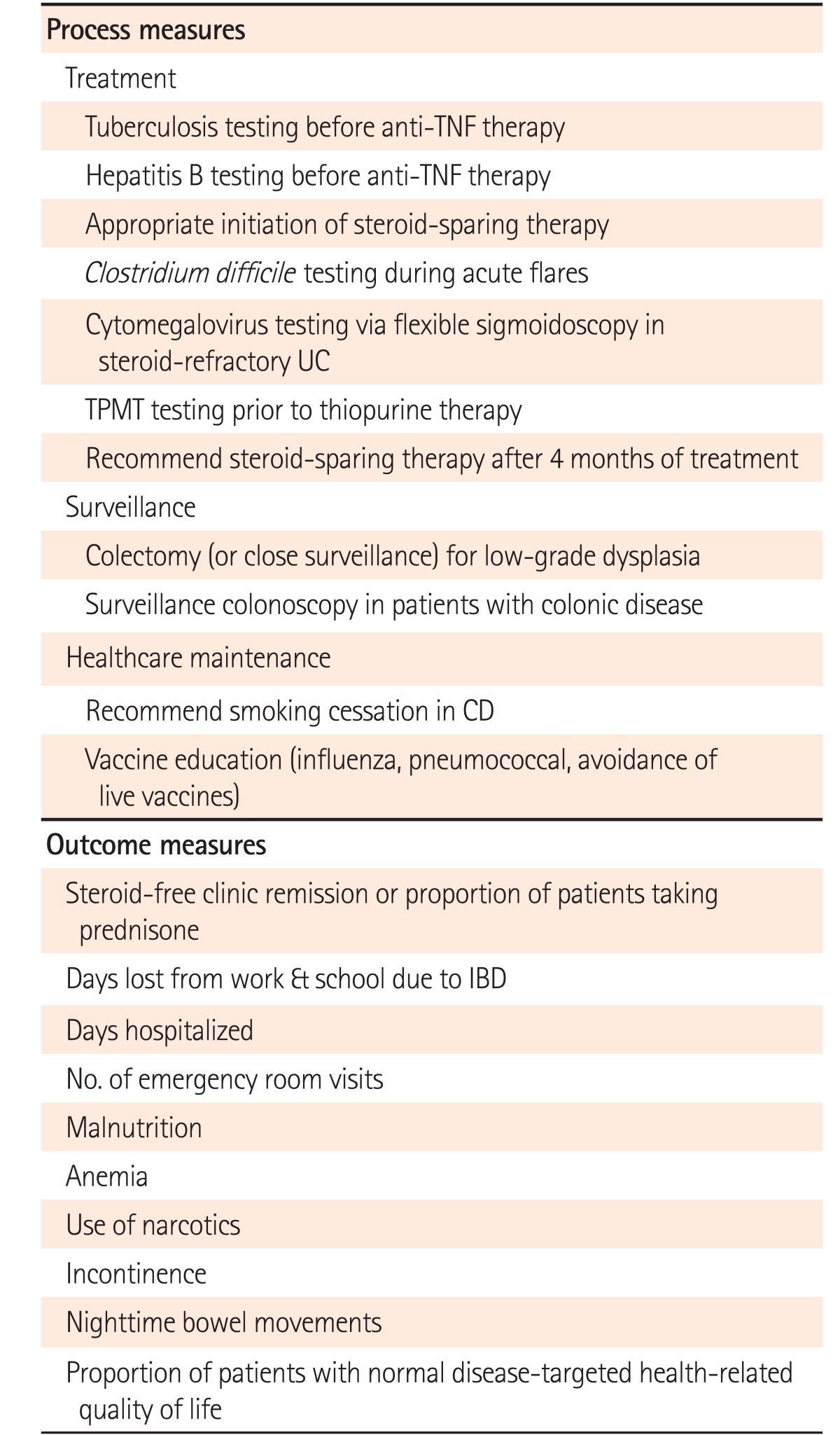

In 2013, the CCFA, a non-profit U.S.-based patient advocacy organization, published 10 process measures and 10 outcome measures (Table 2).9 These measures were developed with input from various IBD stakeholders, including gastroenterologists, nurses, and patients through an iterative process using a modified Delphi panel and 3 in-person meetings. Unlike the AGA measures, the CCFA measures are not used for physician accountability or financial incentives. They have been incorporated into the IBD-Qorus learning health system (see below) and other QI initiatives to help standardize the quality of care for IBD. Standardization of the measurement of processes of outcomes is desired in order to enable comparisons across sites and to assess for improvement over time.

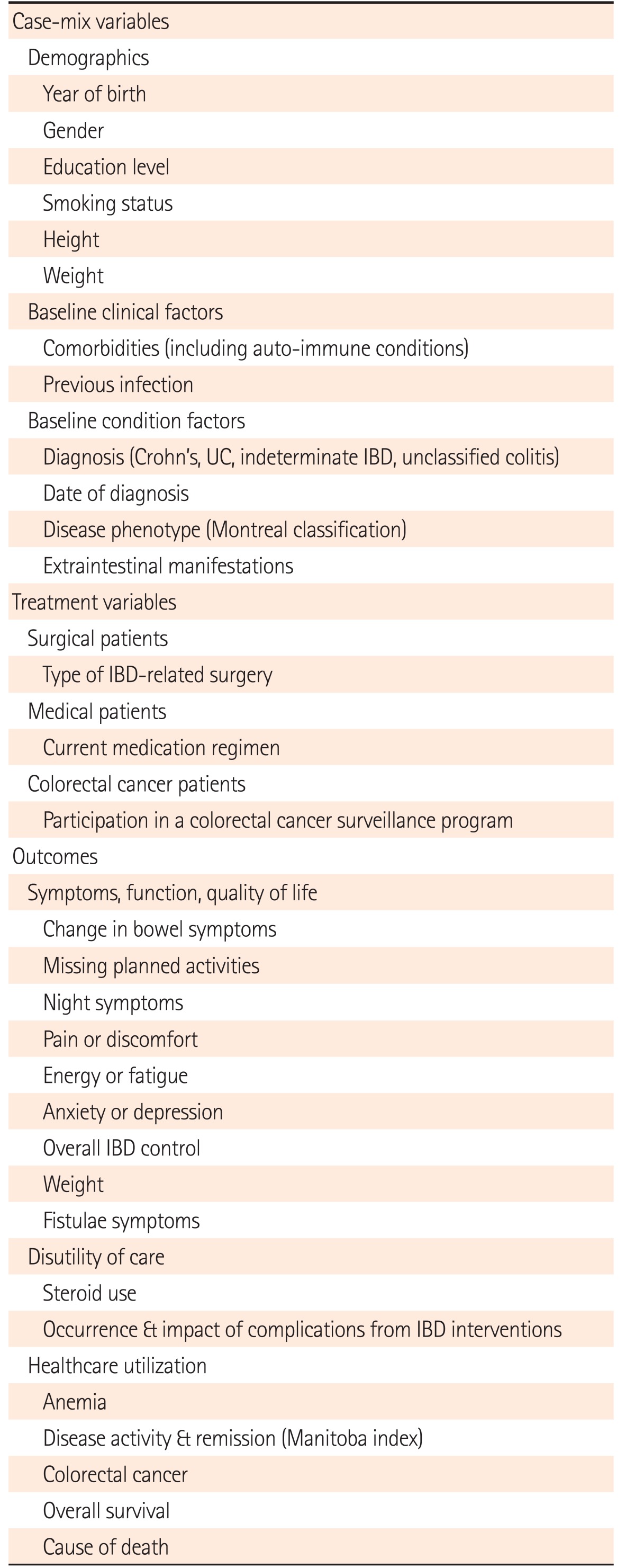

The ICHOM is an organization focused on defining and reporting standardized outcome measure sets across all diseases. This non-profit organization has brought together multiple stakeholders including physicians, outcomes researchers and patient advocates to create standardized outcome sets for each medical condition. This is intended to facilitate comparisons across various organizations caring for patients with IBD globally. The ICHOM outcome set for IBD was completed in 2016 (Table 3) and focuses on the entire care cycle from diagnosis to remission or death.15

In addition to the efforts described above, other international societies have developed quality measures for IBD intended for regional use including gastroenterology societies in Spain and Canada. Calvet et al.14 developed metrics for IBD centers of excellence in Spain; a common theme through many of these metrics is the need for expert, multidisciplinary care teams including specialty IBD nurses. In Canada, quality indicators have recently been developed that broadly address centers of excellence, patient care, and clinical outcomes.16 In addition, a recent effort for the Canadian “Choosing Wisely” campaign to reduce unnecessary or harmful practices has identified 5 aspects of care that should be avoided in patients with IBD; unlike other process measures that recommend appropriate practices,19 these measures represent processes of poor quality of care.

A learning health system is where “science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation, with best practices seamlessly embedded in the delivery process and new knowledge captured as an integral by-product of the delivery experience.” Two successful learning health systems, ImproveCareNow and IBD Qorus, were developed to care for patients with IBD.

ImproveCareNow is a network which allows the sharing of clinical data, patient-reported outcomes, and best practices between patients and providers to improve pediatric IBD care. More than 900 pediatric gastroenterologists and 27,000 patients at 95 care centers in the United States, United Kingdom, and Qatar participate in this learning health system. ImproveCareNow is centered around reducing variation in pediatric IBD care and measuring processes to improve clinical outcomes.2021 To achieve this, it relies on collaboration between multiple care centers to implement change. Physicians submit data on outpatient visits, audit their performance data, and analyze this information during QI meetings. Over the course of several years, ImproveCareNow has demonstrated a steady and significant improvement in the proportion of children who are in clinical remission, have normal growth, and are avoiding steroids.21

IBD Qorus is a learning health system that was developed by the CCFA.22 It was designed to enable rapid data-sharing between physicians and patients to define, measure and improve the quality of care for adult IBD patients. Similar to ImproveCareNow, care teams are taught QI methodology and are encouraged to develop, learn and share best practices from each other. In addition to the platform designed to enhance the sharing of information between the doctor and the patient, standardized care pathways have been incorporated into patient management. These are care algorithms for specific aspects of care that sites may elect to incorporate into their improvement efforts; currently available care pathways include screening and interventions around malnutrition and anemia.2324 A novel aspect of IBD Qorus is that quality metrics are principally reported by patients directly into the electronic platform, rather than providers, which empowers patients to be more involved in their care and reduces the data entry and regulatory burden on providers and their staff.

There has been significant progress in the development of quality indicators for IBD over the past decade, with the availability of dozens of individual structure, process, and outcome measures that have been thoughtfully developed with multi-stakeholder input across multiple organizations. The challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for institutions and practices now relate to the integration of these quality measures into clinical care, and the implementation of QI programs that can show changes in patient outcomes. Measurement of quality using quality indicators is just the first step toward true QI. Future studies should demonstrate whether and how the measurement of quality can lead to reduction in the variation in care delivery, decreased costs, and improved patient outcomes.

Notes

FINANCIAL SUPPORT: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

1. Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008; 135:1907–1913. PMID: 18854185.

2. Esrailian E, Spiegel BM, Targownik LE, Dubinsky MC, Targan SR, Gralnek IM. Differences in the management of Crohn's disease among experts and community providers, based on a national survey of sample case vignettes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007; 26:1005–1018. PMID: 17877507.

3. Spiegel BM, Ho W, Esrailian E, et al. Controversies in ulcerative colitis: a survey comparing decision making of experts versus community gastroenterologists. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 7:168–174.e1. PMID: 18952199.

4. Kappelman MD, Bousvaros A, Hyams J, et al. Intercenter variation in initial management of children with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007; 13:890–895. PMID: 17286275.

5. Viget N, Vernier-Massouille G, Salmon-Ceron D, Yazdanpanah Y, Colombel JF. Opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: prevention and diagnosis. Gut. 2008; 57:549–558. PMID: 18178610.

6. Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, Kane SV. ACG clinical guideline: preventive care in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017; 112:241–258. PMID: 28071656.

7. Mehta F. Report: economic implications of inflammatory bowel disease and its management. Am J Manag Care. 2016; 22(3 Suppl):s51–s60. PMID: 27269903.

8. Ahmed S, Siegel CA, Melmed GY. Implementing quality measures for inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015; 17:14. PMID: 25762473.

9. Melmed GY, Siegel CA, Spiegel BM, et al. Quality indicators for inflammatory bowel disease: development of process and outcome measures. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:662–668. PMID: 23388547.

10. MacLean CH, Louie R, Leake B, et al. Quality of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 2000; 284:984–992. PMID: 10944644.

11. Shekelle PG, MacLean CH, Morton SC, Wenger NS. Acove quality indicators. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 135(8 Pt 2):653–667. PMID: 11601948.

12. Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ. 2003; 326:816–819. PMID: 12689983.

13. Donabedian A. The role of outcomes in quality assessment and assurance. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1992; 18:356–360. PMID: 1465293.

14. Calvet X, Panés J, Alfaro N, et al. Delphi consensus statement: quality Indicators for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Comprehensive Care Units. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:240–251. PMID: 24295646.

15. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) Web site. Inflammatory bowel disease. Accessed May 10, 2017. http://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/inflammatory-bowel-disease/.

16. Nguyen GC, Devlin SM, Afif W, et al. Defining quality indicators for best-practice management of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 28:275–285. PMID: 24839622.

17. Siegel CA, Allen JI, Melmed GY. Translating improved quality of care into an improved quality of life for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 11:908–912. PMID: 23747710.

18. Song HK, Lee KM, Jung SA, et al. Quality of care in inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: the results of a multinational web-based survey in the 2nd Asian Organization of Crohn's and Colitis (AOCC) meeting in Seoul. Intest Res. 2016; 14:240–247. PMID: 27433146.

19. Nguyen GC, Boland K, Afif W, et al. Modified Delphi process for the development of choosing wisely for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017; 23:858–865. PMID: 28509817.

20. Crandall W, Kappelman MD, Colletti RB, et al. ImproveCareNow: the development of a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease improvement network. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:450–457. PMID: 20602466.

21. Crandall WV, Margolis PA, Kappelman MD, et al. Improved outcomes in a quality improvement collaborative for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatrics. 2012; 129:e1030–e1041. PMID: 22412030.

22. Crohn's & Colitis Foundation Web site. IBD Qorus. Accessed May 10, 2017. http://www.crohnscolitisfoundation.org/science-and-professionals/ibdqorus/.

23. Tinsley A, Ehrlich OG, Hwang C, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding the role of nutrition in IBD among patients and providers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22:2474–2481. PMID: 27598738.

24. Hou JK, Gasche C, Drazin NZ, et al. Assessment of gaps in care and the development of a care pathway for anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017; 23:35–43. PMID: 27749376.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download