INTRODUCTION

The role of school lunches is to provide appropriate nutrition to promote growth, development, and health for target students. The nutritional standards for school lunches are designed to provide balanced diets and help to achieve the role of school lunches. It has been reported that the nutrient intake of students who have school lunches is influenced by the nutritional standards for school lunches [

123].

Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) and the nutrient intake data of the target students were used to set reference values for nutritional standards for school lunches in several countries [

45]. In the United States, after setting a daily target intake using the data from the DRIs for Americans, the School Nutrition Dietary Assessment study (SNDA), and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the reference values were set by multiplying the daily target intake by the ratio of energy consumed at lunch out of a day [

6]. In Japan, the reference values were set by multiplying the recommended daily intake of the DRIs for Japanese by a ratio of 33%, 40%, or 50% depending on the kinds of nutrients, considering the nutrient intake of the students using the dietary survey data of elementary and middle school students [

7]. In Taiwan, the reference values were set to one-third or two-fifth of the recommended daily intake based on the DRIs for Taiwanese and the data of elementary and middle school students from the Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan [

89].

However, in South Korea, the nutritional standards for school lunches were established using only the DRIs for Koreans; reference values for each nutrient were set by multiplying uniformly the recommended daily intake of the DRIs by one-third, which signifies the concept of one out of 3 meals [

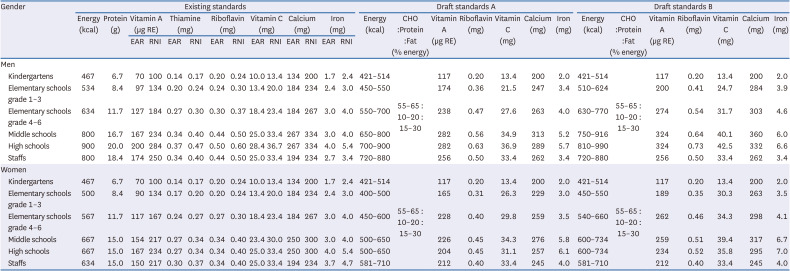

10]. Therefore, it is necessary to employ a scientific method to set the reference values of nutritional standards for school lunches, considering the actual nutrient intake of the target students. Accordingly, through a policy research project ‘Development of Nutritional Standards for School Lunches (Report No. TR 2018-38),’ the Ministry of Education developed new nutritional standards in 2018 using the latest DRIs at the time (i.e., the 2015 DRIs for Koreans) and the data from the 6th KNHANES (KNHANES VI) [

11]. The developed standards were presented as 2 draft standards: A and B. In the 2 standards, the ratio of energy to be provided through school lunches was implemented differently after setting the daily target intake of energy and nutrients [

11].

It is necessary to secure the feasibility of application to increase the effectiveness of the nutritional standards for school lunches developed on the basis of scientific evidence. In the United States, the feasibility of application in the menu planning of nutritional standards for school lunches was evaluated as follows: (1) menus from 397 schools across the nation were collected from the SNDA III data, (2) representative menus were selected for each school level (elementary, middle, and high schools), (3) the representative menus were modified with minimal changes to meet the new nutritional standards, and (4) the menus before and after modification were compared [

6]. In the UK, pilot school lunches applying the new standards were tested for a week at 15 schools representing various school types after developing the nutritional standards for school lunches. The standard recipes and ingredient lists were submitted by the schools, and reviews on the standards were collected from 24 representative British food service providers in order to evaluate the feasibility of application [

12].

South Korea developed the nutritional standards for school lunches in 2004 and conducted a pilot operation of school lunches applying the new standards at 96 schools (32 each of elementary, middle, and high schools) to evaluate the feasibility of application of the standards [

13]. After the pilot operation, the school lunch nutrition management checklist and the pilot operation evaluation form were collected from the schools. The nutritional values and the standard food compositions were then analyzed.

After developing the nutritional standards for school lunches, it is very important to evaluate and improve the feasibility of application through a pilot operation. As mentioned above, a previous study developed the draft nutritional standards for school lunches [

11]. After developing the standards, the pilot operation was conducted to ensure the feasibility of application of the draft standards [

14]. The feasibility of application of the standards can be evaluated from the viewpoints of consumers and suppliers. The results of the pilot operation were divided into 2 parts from the viewpoints of consumers and suppliers. A previous study evaluated the feasibility from the consumer perspective through a survey on students’ and teachers’ satisfaction with the pilot school lunches applying the draft standards [

15]. This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of application of the draft standards from the supplier perspective.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

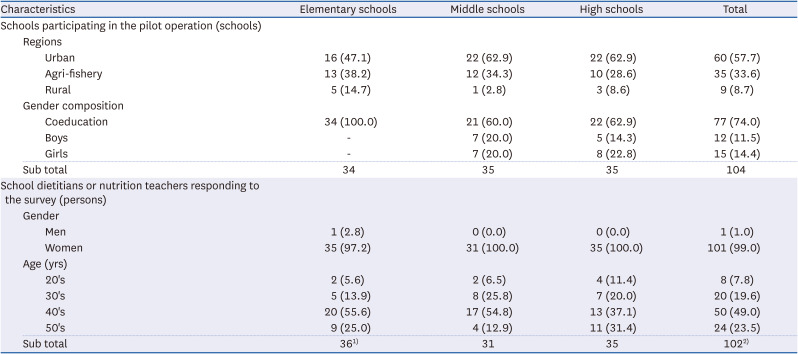

In this study, the feasibility of application of the draft nutritional standards for school lunches was evaluated from the supplier perspective. The pilot operation was conducted at 104 participating schools across the nation by applying the draft standards A and B. The ease and appropriateness of application of the draft standards were evaluated using the school lunch operation data and the survey results.

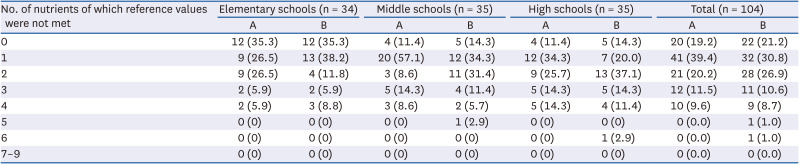

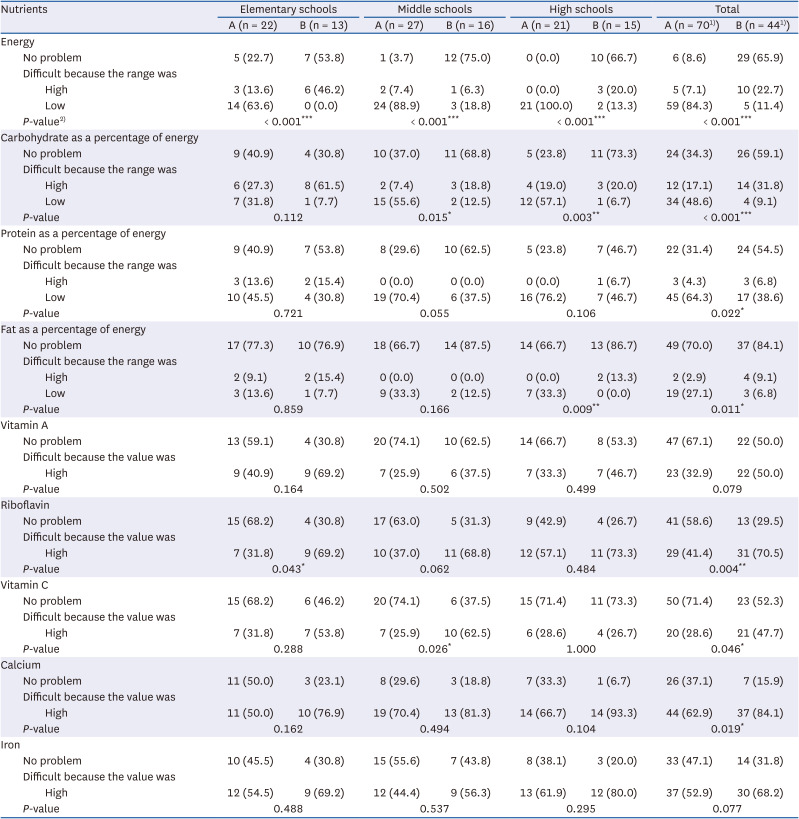

Considering the ease of application in terms of nutritional values, the proportions of schools of which lunches met the reference values of the school’s own nutritional standards for energy and 8 nutrients were low (19.2% for the standards A, 21.2% for the standards B). This could be attributed to the fact that the school dietitians or nutrition teachers were not accustomed to planning menus by applying the draft standards at the time of the pilot operation. Therefore, research on the development of menus and recipes meeting the reference values of new standards is necessary to ensure the feasibility of application of the new standards in school lunch sites.

In the United States and Canada, sample menus for school nutritional standards would be essential because dietitians or nutrition teachers are not staffed in schools. In the United States, the sample menus for breakfast and lunch meeting the reference values of the standards were provided for each school level in consideration of students’ preference and food cost after developing the new school nutritional standards [

6]. In Canada, sample menu handbooks for breakfast and lunch were provided for the application of school nutritional standards, and detailed recipes for each menu were provided for each age group (4−8, 9−13, 14−18 yrs) [

17]. Korean schools are staffed with dietitians or nutrition teachers unlike such countries. Nevertheless, the development of sample menus and recipes would be a great help in applying new nutritional standards for school lunches.

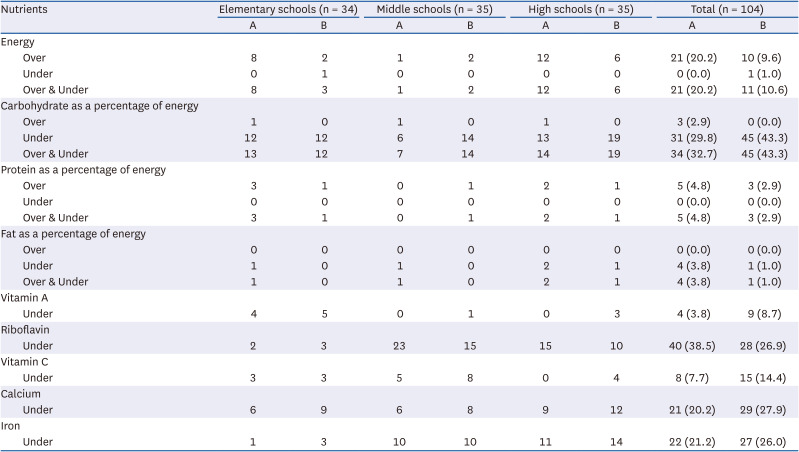

This study showed that the proportion of schools of which lunches had higher nutritional values than the reference values of the draft standards was high in energy and protein as a percentage of energy. This may be because the school dietitians or nutrition teachers considered the students’ preference for high protein and high energy foods when planning menus [

418]. However, school dietitians or nutrition teachers should plan their menus to meet the reference ranges rather than focusing on the students’ preferences. The reference ranges of energy and macronutrients as percentages of energy of the nutritional standards for school lunches were established based on the 2015 DRIs for Koreans. The DRIs presented the estimated energy requirements and the acceptable macronutrient distribution range for adequate intake of energy and macronutrients among Koreans [

19]. Obesity caused by excessive energy intake is a major health problem that increases the risk of chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes [

202122]. In addition, it has been reported that the composition of macronutrients as percentages of energy is related to health [

2223].

On the other hand, nutrients with a high proportion of schools of which lunches had lower nutritional values than the reference values were riboflavin, calcium, and iron. In a study analyzing the nutritional values provided by school lunches in Korea [

24], the nutritional values of riboflavin, calcium, and iron did not meet one-third of the recommended daily intake of DRIs in some target student groups. Korea Health Statistics 2018 [

25] reported that the ratios of actual intake to recommended daily intake were 148.8% and 133.6% for riboflavin, 65.6% and 63.7% for calcium, and 91.4% and 79.8% for iron in the 6−11 and 12−18 years age groups, respectively. These results showed that the nutritional values from school lunches as well as the actual intake of the target students might have been insufficient, especially in calcium and iron. Therefore, school lunches should provide sufficient riboflavin, calcium, and iron.

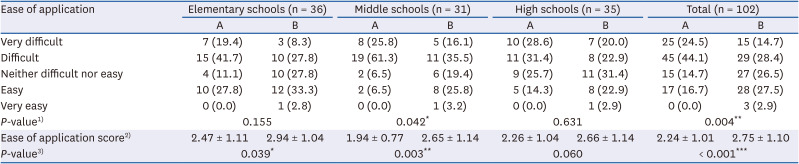

This study showed that the standards B were more applicable than the standards A. The mean score for the ease of application was higher for the standards B (2.75) than for the standards A (2.24). A previous study [

18] reported that school dietitians or nutrition teachers in the Chungbuk region considered energy and protein the most important when planning menus. The nutritional values exceeded the reference values of the nutritional standards in protein (41.9%), energy (36.2%), calcium (9.8%), and vitamins (7.9%) [

18]. The standards B might have been easier to apply because the reference ranges of energy and protein as a percentage of energy were higher than those of the standards A.

The school dietitians or nutrition teachers reporting difficulty in meeting the reference values of the draft standards answered reasons for the difficulty as follows: the low reference ranges of energy (84.3%) and protein as a percentage of energy (64.3%) for the standards A, and the high reference values of calcium (84.1%), riboflavin (70.5%), and iron (68.2%) for the standards B. It has been reported that energy and macronutrients such as protein and fats tend to exceed the reference ranges when planning school lunch menus, while micronutrients such as calcium, iron, and vitamins tend to be excessive or insufficient depending on food selection [

1826]. The school dietitians or nutrition teachers might have felt difficulty in meeting the reference ranges of energy and protein as a percentage of energy because they have low reference ranges in the standards A. On the other hand, the respondents might have felt difficulty in meeting the reference values of calcium, riboflavin, and iron because the reference values of vitamins and minerals were set relatively higher in the standards B than in the standards A.

In this study, it was difficult to meet the reference values because of the lower reference ranges of energy and protein as a percentage of energy for the standards A and the higher reference values of calcium and riboflavin for the standards B as the school level increased. According to a previous study [

4], it becomes more difficult to plan menus meeting the reference values of nutritional standards as the school level increases from elementary to middle to high schools. In particular, it is difficult to meet the reference value of calcium as the school level increases [

418]. The proportions of students who consumed milk in Korean schools were 72.5% for elementary schools, 33.9% for middle schools, and 21.3% for high schools in 2019 [

27]. This might have been the reason for the difficulty in meeting the reference values of calcium and riboflavin only with school lunches as the school level increased, considering that milk and dairy products are good sources of calcium and riboflavin [

21].

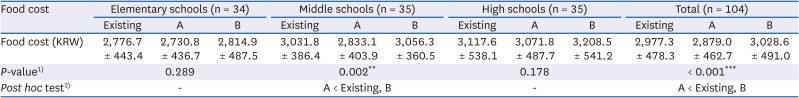

Considering the ease of application in terms of food cost, there was no significant difference in the food cost of school lunches applying the existing standards and standards B. The average food cost of school lunches applying the standards A (KRW 2,880) was lower than that of school lunches applying the existing standards (KRW 2,980) or the standards B (KRW 3,030). The food cost of school lunches applying the standards A was considered relatively low because the reference values of the standards A were set lower than those of the existing standards or the standards B. Therefore, there would be no food cost issue when planning menus by applying the standards B.

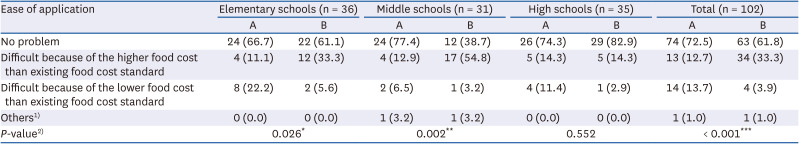

In addition, 72.5% and 61.8% of school dietitians or nutrition teachers reported no problem in meeting the existing food cost standard when planning menus by applying the standards A and B, respectively. Food cost is known to be an important factor for most school dietitians or nutrition teachers in menu planning. According to a study on nutrition management for school lunch programs in Seoul and Incheon provinces [

28], food cost is the third highest priority among the 6 factors considered by school dietitians or nutrition teachers. Furthermore, school dietitians or nutrition teachers in the Chungbuk region considered food cost the most important and difficult factor [

18]. In this study, the ease of application in terms of food cost was found to be high in both standards A and B. Therefore, both standards were judged appropriate for field application.

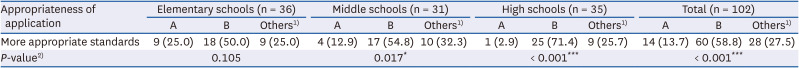

The overall appropriateness of application of the draft standards was found to be higher for the standards B than for the standards A. Almost two-thirds (58.8%) of the school dietitians or nutrition teachers answered that the standards B were more appropriate standards. This is considered to be because the ease of application in terms of nutritional values was higher for the standards B than for the standards A, and both standards showed high ease of application in terms of food cost.

In conclusion, the feasibility of application of the draft nutritional standards for school lunches evaluated from the supplier perspective was higher for the standards B than for the standards A. The standards B showed higher ease of application than the standards A in terms of nutritional values, and both standards A and B showed high ease of application in terms of food cost. The overall appropriateness of application was higher for the standards B than for the standards A.

Our attempt in this study was to prepare the basis for new nutritional standards for school lunches, which were about to be revised at the time. However, the nutritional standards for school lunches in South Korea, revised in 2021, were set using the existing method of uniformly multiplying the recommended nutrient intake of the 2015 DRIs for Koreans by 1/3 for each nutrient. Since the existing method is based only on the DRIs, it has a limitation of reflecting the actual nutrient intake of the target students insufficiently. In the future, it is necessary to revise the nutritional standards for school lunches by applying a scientific method that can reflect the actual nutrient intake of the target students, not based only on DRIs.

In this study, sodium and sugar were not included in the draft nutritional standards because the exact recipes for the amount of sodium or sugar added during cooking school lunches have not been established. In the future, sodium and sugar should be considered to be included in the nutritional standards for school lunches.

This study is significant since it tried to verify the feasibility of application of the draft nutritional standards for school lunches through a systematic pilot operation. In the future, the results of this study can be used as valuable information to evaluate and improve the feasibility of application of the nutritional standards for school lunches in South Korea as well as other countries.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download