Abstract

Purpose

Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (LPPG) has a nutritional advantage over laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG), however, may be less beneficial in overweight patients in terms of weight loss. The purpose of this study was to compare LPPG and LDG in overweight patients with early gastric cancer.

Methods

Clinicopathologic data of overweight patients (body mass index [BMI], ≥25 kg/m2) who underwent LPPG (n = 63) or LDG (n = 183) in 2016–2018 were retrospectively reviewed. In the LDG group, patients with Billroth-II anastomosis were separately grouped (LDG B-II, n = 66). Changes in BMI, hemoglobin, albumin, and total protein were compared among groups.

Results

Changes in BMI were not significant different among groups. The LPPG group had significantly higher albumin than the LDG group at postoperative 6 months and 1 year. The LPPG group had higher total protein than the LDG group at postoperative 2 years. The LPPG group had a higher complication rate of Clavien-Dindo classification III or higher (20.6%) than the LDG group (8.2%, P = 0.007). However, after excluding pyloric stenosis, there was no significant difference among groups (LPPG vs. LDG, P = 0.290; LPPG vs. LDG B-II, P = 0.921).

Conclusion

LPPG and LDG groups showed similar weight loss. However, the LPPG group had higher albumin and protein levels than the LDG group of overweight patients. Thus, it is not necessary to select LDG only for weight loss. LPPG may be selected as one option due to its potential nutritional benefit when pyloric stenosis is properly managed.

Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG), a representative function-preserving gastrectomy, was developed for benign ulcer. It is currently being used for early gastric cancer located in the middle stomach [1].

Although PPG is not so frequently performed in Korea [2], several reports have shown that PPG can be beneficial in terms of less body weight loss, better preservation of nutrition, and less incidence of diarrhea of dumping syndrome in comparison with other gastrectomy methods [345].

Whether laparoscopic PPG (LPPG) is also beneficial to overweight patients has not been well studied. Although LPPG might help preserve the quality of life of patients by reducing dumping syndrome or diarrhea, maintenance of high body mass index (BMI) might be rather harmful considering its associations with obesity and various cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [6].

To select an appropriate surgical method for early gastric cancer patients with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher, this study compared changes in BMI, nutritional changes, and complications between laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (LDG) and LPPG before and after surgery.

Medical records of patients at Seoul National University Hospital from 2016 to 2018 were reviewed retrospectively. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (No. H-2112-068-1281). It was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent is exempt because it is a retrospective study.

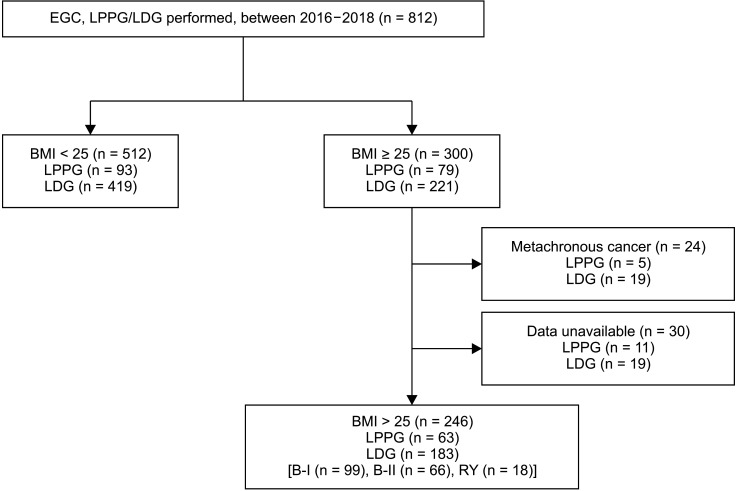

Among a total of 812 patients who underwent LDG or LPPG for clinical stage I early gastric cancer [7], 300 patients were identified to have a preoperative BMI of ≥25 kg/m2. After excluding patients with metachronous cancer or data loss, 246 patients (63 patients in the LPPG group and 183 patients in the LDG group) were selected for analysis. In the LDG group, patients with Billroth-II anastomosis were separately grouped (LDG B-II, n = 66) to adjust for the possibility of different sizes of the proximal remnant stomach (Fig. 1).

Operations were performed by 4 experienced surgeons. Surgical procedures for LPPG and LDG were the same as previously reported [58]. The infrapyloric artery and vein, the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve, and the first branch of the right gastric artery were preserved without complete lymph node dissection of station 5. Extent of lymph nodes of LPPG was D1+ in most cases. Partial or complete dissection of station 11p was performed in selected patients according to the location of the tumor and surgeon’s discretion. D1+ or D2 dissection was performed for the LDG group. The pyloric cuff was 3 cm in most extracorporeal anastomosis cases. The cuff could be longer than 3 cm in cases with intracorporeal anastomosis [91011].

Demographic data such as age, sex, BMI, weight, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification, comorbidity, pathological TNM stage, and short-term surgical results were obtained from the medical records of Seoul National University Hospital.

The TNM stage was organized through the TNM staging system of Union for International Cancer Control, 8th edition. Postoperative complications were classified according to Clavien-Dindo classification [12].

BMI was measured in the same place at the outpatient clinic of the gastric cancer center. BMI and blood tests including serum total protein, albumin, and hemoglobin were assessed preoperatively and postoperative 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years with 2 months of windows. The graphs of changes in BMI and nutritional indicators before and after surgery were made using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, California). In order to predict the cut-off value of the preoperative BMI when the postoperative BMI was 25 kg/m2 or less for each operation, the BMI section was analyzed.

To compare clinical parameters between groups, the chi-square test was used for categorical variables and the Student t-test was used for continuous variables. Data repeatedly measured in the same subject were analyzed using a mixed linear test. In the mixed linear test, if the effect according to time was proven to be significant in the time-group interaction test, a post-hoc test was performed with the significance level corrected to see at what point the initial value showed a significant difference. Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation or median (range). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

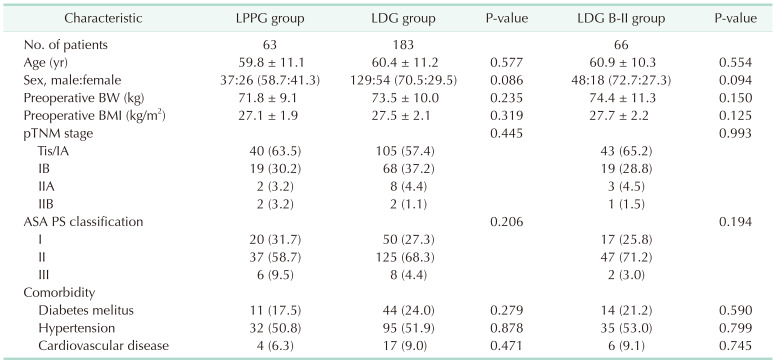

Clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in clinicopathologic characteristics among LPPG, LDG, and LDG B-II groups. The LPPG group showed a tendency of higher proportion of female patients. However, the difference was not statistically significant.

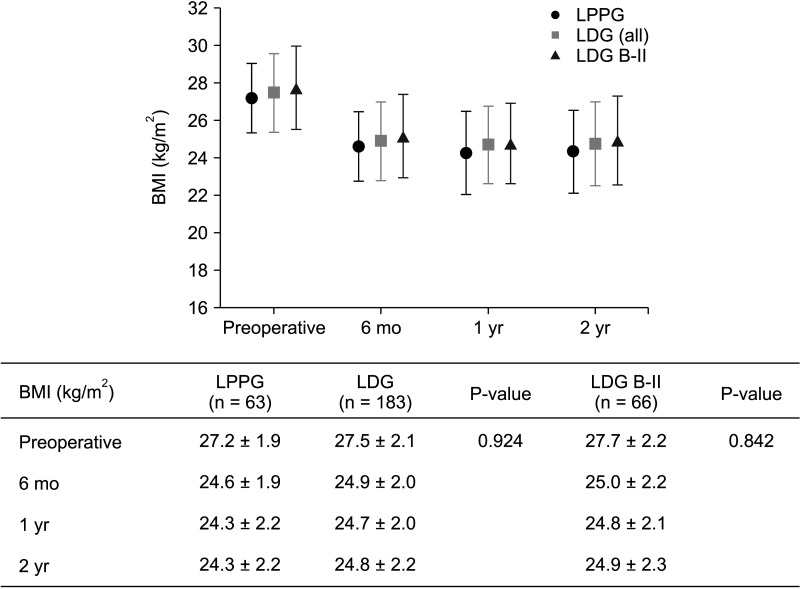

BMI changes in LPPG, LDG, and LDG B-II groups showed no significant difference (Fig. 2). BMI changes at 1 year after surgery in LPPG, LDG, and LDG B-II groups were –2.88 ± 1.59, –2.75 ± 1.49, and –2.93 ± 1.44 kg/m2, respectively. They were not different according to the vertical location of the tumor (upper and middle thirds vs. lower third) either (Supplementary Table 1).

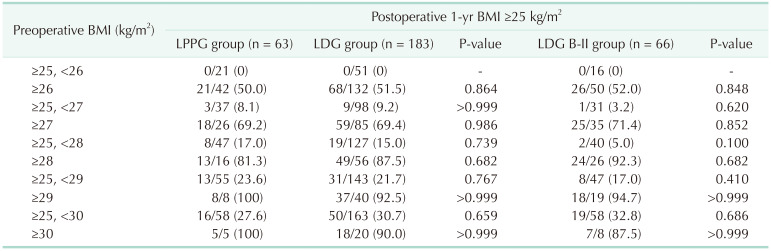

In both LPPG and LDG groups, if BMI exceeded 26 kg/m2, postoperative BMI was maintained at 25 kg/m2 or higher in more than 50% of patients. In over 80% of cases with a preoperative BMI of 28 kg/m2 or higher, almost all patients with a preoperative BMI of 29 kg/m2 or higher maintained a postoperative BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher (Table 2).

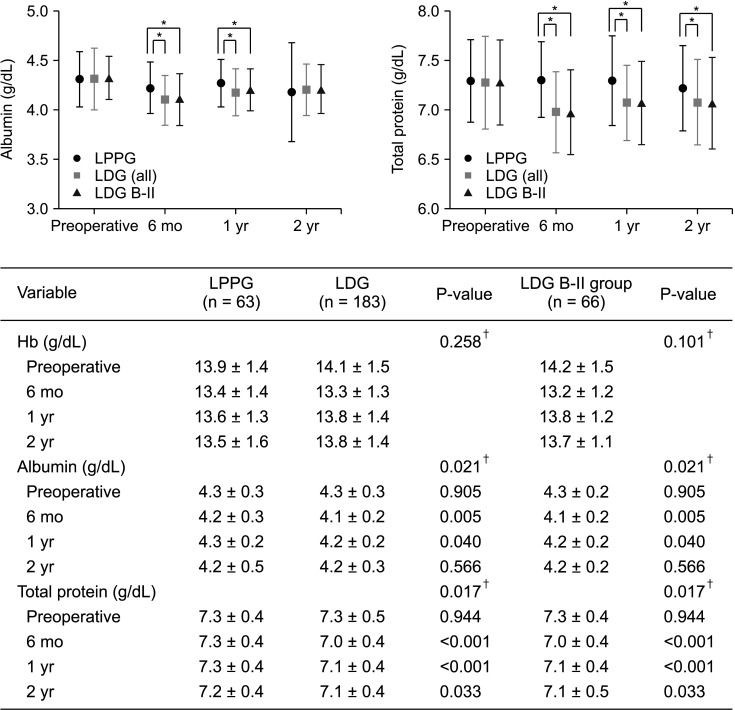

Albumin showed a smaller decrease in LPPG than in LDG at 6 months and 1 year after surgery. The difference between the 2 groups was significant (6 months, P = 0.005; 1 year, P = 0.040). Total protein decreased less in LPPG than in LDG at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery. The difference between the 2 groups was statistically significant (6 months, P < 0.001; 1 year, P < 0.001; and 2 years, P = 0.033) (Fig. 3).

Hemoglobin levels before and after surgery were similar between the 2 groups, showing no significant difference.

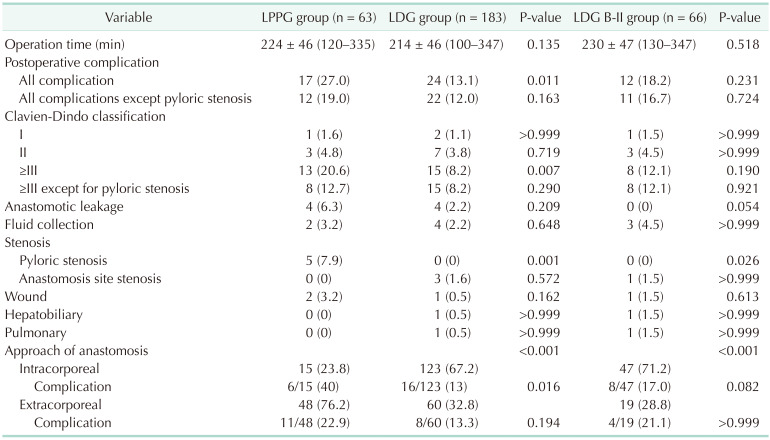

There was no difference in average operation time between LDG and LPPG groups (Table 3).

Postoperative complications occurred more in the LPPG group than in the LDG group, showing a significant difference (27.0% in LPPG vs. 13.1% in LDG, P = 0.011). However, when comparing the incidence of complications except for pyloric stenosis, it was similar between the 2 groups (19.0% in LPPG vs. 12.0% in LDG, P = 0.163).

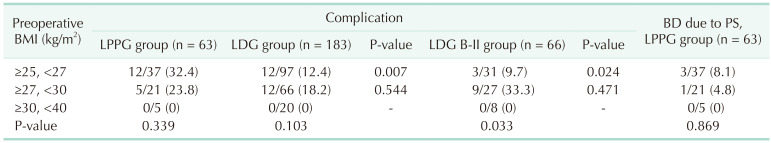

Complication rates were compared by the preoperative BMI section. Results are shown in Table 4. For BMI of ≥25 and <27 kg/m2, the incidence of complications was significantly higher in LPPG than in LDG or LDG B-II (32.4% in LPPG vs. 12.4% in LDG, P = 0.007; 32.4% in LPPG vs. 9.7% in LDG B-II, P = 0.024). On the other hand, there was no difference in the incidence of complications between LPPG and LDG (or LDG B-II) in BMI of 27 kg/m2 or higher.

There were 4 cases of pyloric stenosis requiring balloon dilatation in the LPPG group. And the frequency of balloon dilatation did not increase as the BMI increased in the LPPG group.

The purpose of this study was to find the optimal surgical method for patients with BMI of ≥25 kg/m2, which is defined as overweight or obese according to the World Health Organization general population BMI classification [13], among early gastric cancer patients.

Previous studies that did not limit BMI showed less body weight loss after PPG compared to that after distal gastrectomy (DG) [141516]. Based on these studies, we considered that LPPG might be less beneficial to overweight patients in terms of maintenance of overweight status, which is associated with various metabolic diseases.

However, the present study focusing on overweight patients showed no difference in weight loss between LPPG and LDG. When we compared LPPG with all types of LDG, a significant proportion of LDG might consist of cancer in the lower third of the stomach, which can affect the comparability in terms of remaining remnant stomach volume. Thus, we additionally compared LPPG with only LDG B-II anastomosis, which is more likely to have a similar resection line with LPPG. Nevertheless, we could not find any difference in weight loss between the 2 groups. Therefore, it seems unreasonable to select LDG only for greater weight loss in patients with high BMI based on our data.

The little difference in weight loss change between PPG and DG may be explained by greater weight loss after PPG in our study than previous studies which did not focus on the high BMI patients [171819]. We speculate that the difficulty of lymph node dissection around the infrapyloric area with preservation of infrapyloric vessels in overweighted patients might have resulted in direct or indirect injuries around the pylorus. These injuries possibly decreased the function of the pylorus and limited food uptake by delayed gastric emptying and/or loss of appetite [20], although it may not be proven without gastric emptying time test.

When considering acceptable upper limit of BMI as 25 kg/m2, which is usually defined as target BMI for weight loss in bariatric surgery, we tried to estimate how much proportion of patients would remain BMI over 25 kg/m2 after surgery by grouping patients according to BMI section. The majority of patients in our series maintained their BMI over 25 kg/m2 after surgery regardless of LPPG or LDG. Most patients with preoperative BMI of ≥28 kg/m2 did not reach less than BMI of 25 kg/m2 after LPPG or LDG. Thus, we may not expect a weight loss effect by performing conventional gastrectomy for those patients.

Unlike little differences in body weight change, LPPG showed better preservation of serum albumin and protein levels in this study. Better preservation of albumin and protein levels has been shown in previous studies without limitation of BMI [141516171819]. Preservation of the pylorus could be helpful to maintain controlled slow transit through the duodenum and proximal jejunum and to preserve the absorption of protein [21]. Regarding the nutritional aspect, LPPG might have benefits for patients if patients do not have other metabolic diseases.

Other studies have reported less hemoglobin loss in DG Billroth-I anastomosis (DG B-I) compared to DG Billroth-II anastomosis (DG B-II) [2223]. This may be interpreted by a bypassing effect of the duodenum in DG B-II, where iron absorption is maximal. We expected similar results in our series. However, there was no difference in hemoglobin levels between PPG and DG B-II for an unknown reason.

On the other hand, LPPG resulted in more complications than LDG in this study. The main difference was in the proportion of pyloric stenosis in LPPG as reported in previous studies [5911]. In spite of higher incidence of pyloric stenosis in PPG, the total complication rate was similar between PPG and DG in previous studies [9], which might be due to fewer occurrences of complications other than pyloric stenosis in the PPG group with relatively lower BMI that might be associated with less extent of dissection. However, in overweight patients, the effect of fewer complications other than pyloric stenosis did not differ between PPG and DG in our study. Thus, the overall complication rate was higher in PPG.

We hypothesized that increased BMI might have affected a higher incidence of complications. However, the incidence of overall complication and pyloric stenosis was not directly associated with BMI section in our subgroup analysis (Table 4). However, a recent report from a multicenter randomized trial (KLASS-04) has suggested that BMI is risk factor of pyloric stenosis [9]. The incidence of pyloric stenosis in our study (8.0%) was near the upper limit of the range of previous studies (5%–8%) [9111415], suggesting possibly more injuries around the pylorus in overweight patients. However, 5 patients who developed pyloric stenosis were well managed by balloon dilatation (n = 4) or conservative management (n = 1) without long-term sequelae.

This study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study conducted at a single center and the LDG group was composed of highly variable cases with different extents of resection of the stomach. Although we tried to compensate for the limitation by additional analysis with only the LDG B-II group, there was a limitation of comparability. Second, effects on metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension could not be compared due to the unavailability of data from a retrospective medical record review. Although a few studies suggested a better effect on glucose control in Billroth-II anastomosis than in Billroth-I anastomosis, whether conventional DG B-II anastomosis could be sufficient as metabolic surgery remains unclear [2425]. In our series, LDG did not show any better effect on body weight loss, which is one important aspect in metabolic surgery. Therefore, to obtain enough metabolic effects for those patients, we may not choose LDG instead of LPPG. We may consider more effective metabolic surgery methods.

On the other hand, we could identify some patients with diabetes in the LPPG group. Unlike concerns that diabetes might affect the function of the pylorus via neuropathic or vascular disturbance, most diabetic patients did not suffer from pyloric stenosis or delayed emptying. Thus, we may think that mild diabetes without major complications, at least, is not needed to be excluded from indication of LPPG.

In conclusion, when compared with LDG, LPPG showed no difference in body weight change. Although LPPG showed advantage of better preservation of albumin and protein, it had a disadvantage of higher complication rate in patients with BMI of ≥25 kg/m2. Its higher complication rate was mainly due to more frequent development of pyloric stenosis, which was successfully managed with non-surgical treatment.

Therefore, it does not seem necessary to select conventional LDG only for the purpose of weight loss in overweight patients. LPPG could be an option to obtain better nutritional benefit if it is combined with proper management of pyloric stenosis.

References

1. Sasaki I, Fukushima K, Naito H, Matsuno S, Shiratori T, Maki T. Long-term results of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for gastric ulcer. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1992; 168:539–548. PMID: 1306602.

2. Information Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. Korean Gastric Cancer Association-led nationwide survey on surgically treated gastric cancers in 2019. J Gastric Cancer. 2021; 21:221–235. PMID: 34691807.

3. Hotta T, Taniguchi K, Kobayashi Y, Johata K, Sahara M, Naka T, et al. Postoperative evaluation of pylorus-preserving procedures compared with conventional distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2001; 31:774–779. PMID: 11686554.

4. Yamaguchi T, Ichikawa D, Kurioka H, Ikoma H, Koike H, Otsuji E, et al. Postoperative clinical evaluation following pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004; 51:883–886. PMID: 15143939.

5. Park DJ, Lee HJ, Jung HC, Kim WH, Lee KU, Yang HK. Clinical outcome of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy in gastric cancer in comparison with conventional distal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis. World J Surg. 2008; 32:1029–1036. PMID: 18256877.

6. Park YS, Park DJ, Lee Y, Park KB, Min SH, Ahn SH, et al. Prognostic roles of perioperative body mass index and weight loss in the long-term survival of gastric cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018; 27:955–962. PMID: 29784729.

7. Guideline Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association (KGCA). Development Working Group & Review Panel. Korean Practice Guideline for Gastric Cancer 2018: an evidence-based, multi-disciplinary approach. J Gastric Cancer. 2019; 19:1–48. PMID: 30944757.

8. Alzahrani K, Park JH, Lee HJ, Park SH, Choi JH, Wang C, et al. Short-term outcomes of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: comparison between extracorporeal and intracorporeal gastrogastrostomy. J Gastric Cancer. 2022; 22:135–144. PMID: 35534450.

9. Park DJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Ryu KW, Han SU, Kim HH, et al. Short-term outcomes of a multicentre randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy with laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer (the KLASS-04 trial). Br J Surg. 2021; 108:1043–1049. PMID: 34487147.

10. Oh SY, Lee HJ, Yang HK. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2016; 16:63–71. PMID: 27433390.

11. Hiramatsu Y, Kikuchi H, Takeuchi H. Function-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021; 13:6223. PMID: 34944841.

12. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004; 240:205–213. PMID: 15273542.

13. World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight [Internet]. Geneva: WHO;2021. cited 2021 Jun 9. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

.

14. Suh YS, Han DS, Kong SH, Kwon S, Shin CI, Kim WH, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy is better than laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for middle-third early gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2014; 259:485–493. PMID: 23652333.

15. Tsujiura M, Hiki N, Ohashi M, Nunobe S, Kumagai K, Ida S, et al. Should pylorus-preserving gastrectomy be performed for overweight/obese patients with gastric cancer? Gastric Cancer. 2019; 22:1247–1255. PMID: 30888536.

16. Jiang X, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Fukunaga T, Kumagai K, Nohara K, et al. Postoperative outcomes and complications after laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2011; 253:928–933. PMID: 21358534.

17. Fujita J, Takahashi M, Urushihara T, Tanabe K, Kodera Y, Yumiba T, et al. Assessment of postoperative quality of life following pylorus-preserving gastrectomy and Billroth-I distal gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients: results of the nationwide postgastrectomy syndrome assessment study. Gastric Cancer. 2016; 19:302–311. PMID: 25637175.

18. Xia X, Xu J, Zhu C, Cao H, Yu F, Zhao G. Objective evaluation of clinical outcomes of laparoscopy-assisted pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for middle-third early gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019; 19:481. PMID: 31117975.

19. Tsujiura M, Hiki N, Ohashi M, Nunobe S, Kumagai K, Ida S, et al. Excellent long-term prognosis and favorable postoperative nutritional status after laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017; 24:2233–2240. PMID: 28280944.

20. Wang CJ, Suh YS, Lee HJ, Park JH, Park SH, Choi JH, et al. Postoperative quality of life after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients: a prospective longitudinal observation study. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2022; 103:19–31. PMID: 35919110.

21. Schölmerich J. Postgastrectomy syndromes: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004; 18:917–933. PMID: 15494286.

22. Lim CH, Kim SW, Kim WC, Kim JS, Cho YK, Park JM, et al. Anemia after gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: long-term follow-up observational study. World J Gastroenterol. 2012; 18:6114–6119. PMID: 23155340.

23. Rogers C. Postgastrectomy nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011; 26:126–136. PMID: 21447764.

24. Pinheiro JS, Schiavon CA, Pereira PB, Correa JL, Noujaim P, Cohen R. Long-long limb Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is more efficacious in treatment of type 2 diabetes and lipid disorders in super-obese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008; 4:521–527. PMID: 18539540.

25. Kwon Y, Kim HJ, Lo Menzo E, Park S, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of Billroth reconstruction on type 2 diabetes: a new perspective on old surgical methods. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015; 11:1386–1395. PMID: 25892345.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary Table 1 can be found via https://doi.org/10.4174/astr.astr.2023.104.1.18.

Supplementary Table 1

Comparison of changes in BMI before and 1 year after surgery according to LPPG and LDG in upper and middle lesion

Fig. 1

Flowchart showing the selection of study subjects. EGC, early gastric cancer; LPPG, laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy; LDG, laparoscopic distal gastrectomy; BMI, body mass index; B-I, Billroth-I anastomosis; B-II, Billroth-II anastomosis; RY, Roux-en-Y anastomosis.

Fig. 2

Changes in body mass index (BMI) before and after surgery. Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (mixed linear test). The P-value is the value of the time and group interaction test. 6 mo, 6 months postoperative; 1 yr, 1 year postoperative; 2 yr, 2 years postoperative; LPPG, laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy; LDG, laparoscopic distal gastrectomy; B-II, Billroth-II anastomosis.

Fig. 3

Changes in nutritional indicators. Values are shown as mean ± standard deviation, mixed linear test. The P-value of hemoglobin is the time point and group interaction test value, and the P-value of albumin and total protein is the post-hoc test value comparing the groups at each time point. 6 mo, 6 months postoperative; 1 yr, 1 year postoperative; 2 yr, 2 years postoperative; LPPG, laparoscopic pylorus-preserving gastrectomy; LDG, laparoscopic distal gastrectomy; B-II, Billroth-II anastomosis. *P<0.05. †P-value of time and group interaction test.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download