INTRODUCTION

Patient education refers to instructions regarding a patient’s health, with the ultimate goal of long-term health improvement.

1 In addition to verbal education, patient educational materials increase the overall effectiveness of patient education.

2 The information in these materials is mainly provided via face-to-face interactions; phone interactions with medical staff; written formats, such as educational pamphlets and brochures; online educational content; and audiovisual formats, such as video and audio materials.

3 The content of patient educational materials typically includes information and guidance about surgeries or procedures, tests, post-procedure self-care, diseases, preoperative preparation, and patient diets.

4 These materials supplement verbal education and facilitate at-home patient learning.

56 Furthermore, written educational information helps patients and guardians to retain more information and overcome the “one-way process” wherein experts deliver large amounts of information without tailoring the delivery to individual patients.

7

The Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare and Korea Health Information Service implemented an electronic medical record (EMR) certification system in 2020.

8 This certification system encourages companies to develop standardized products by verifying the national standards for domestic EMR systems to facilitate the provision of quality medical services and promote EMR system improvements such as system interoperability.

8 The system’s evaluation criteria for “patient information provision” includes the “provision of patient-specific educational materials” (PEMs) and “patient healthcare information notification.”

9 Patient educational materials should comprise patient-tailored content to facilitate patient disease management and provide notifications about patient healthcare. In addition to the EMR certification system, national efforts should be made for quality control and verification of patient educational materials.

10

Since 2015, the meaning and technical presentation of PEMs have been regulated by the Office of the National Coordinator in Health IT Certification Program Section “170.315(a)(13) Patient-specific educational resources” wherein patient-specific educational resources are identified based on patient data, such as a list of their medical conditions and medications.

11

Previous studies have examined how patient educational materials in a specific field should be provided

145612 and the materials that are the most effective.

131415 Today, high-quality PEMs can be provided using an efficient tool, the EMR system. Thus, it is important to identify suitable conditions, including the socioeconomic policy environment, for the provision of PEMs via the EMR system. In this study, we examined the selection of patient-specific educational content, the methods by which these materials can be provided, and how these materials can be produced.

In this mixed-method research, we conducted expert interviews and Delphi surveys to produce and distribute PEMs. The study findings would offer insights into the fee-setting process and evaluation standards for the provision of these materials.

METHODS

This study aimed to identify the requirements for the effective provision of PEMs and determine how these requirements should be implemented. To address this aim, we conducted a qualitative analysis of responses obtained through expert interviews to identify these requirements, and based on the results; we quantitatively analyzed the responses provided by clinical-field workers to the questions in the Delphi surveys.

Respondent selection

Healthcare providers (doctors and nurses) with clinical experience, patient safety experts, medical information system experts, and patient educational content experts were interviewed and surveyed. These interviews and surveys were conducted from October to December 2021. The face-to-face advisory interview participants were selected based on the correlation of their specialties to the research topic. Moreover, all the face-to-face advisory interviewees were experts in tertiary medical institutions.

The expert interviews were conducted with one patient educational material expert who works in a material development/management department of a medical institution (patient education material expert 1, PM1) and two experts in patient educational material systems (material system experts 1 and 2, MS1 and MS2). MS1 is an expert in EMR system prescriptions, involving patient educational materials and automatic prescription functions. MS2 is an expert in EMR systems and patient educational material management. In addition, we also interviewed two patient education experts (patient education experts 1 and 2, PE1 and PE2). PE1 is an expert who has previously participated in government research on patient educational materials development. PE2 is an expert with clinical experience who had previously participated in government research related to patient educational counseling and examination policy.

Questionnaire and survey design

We used a flexible, semi-structured expert interview format since we could not administer the same questions to all respondents due to their varying fields of expertise.

16 Semi-structured in-depth individual interviews are a set of predetermined open-ended questions and other questions that emerge from the dialog between an interviewer and interviewee.

16 The interview outline was provided to participants before the interviews. All interviews were conducted individually and recorded, and the questions were transcribed into Korean. The interviews lasted between 60 and 120 minutes.

For the surveys, we used the Delphi method of gathering the collective opinions of a group of experts regarding a particular topic.

17 The content validity of the Delphi surveys was ensured by involving expert panelists and conducting iterative rounds.

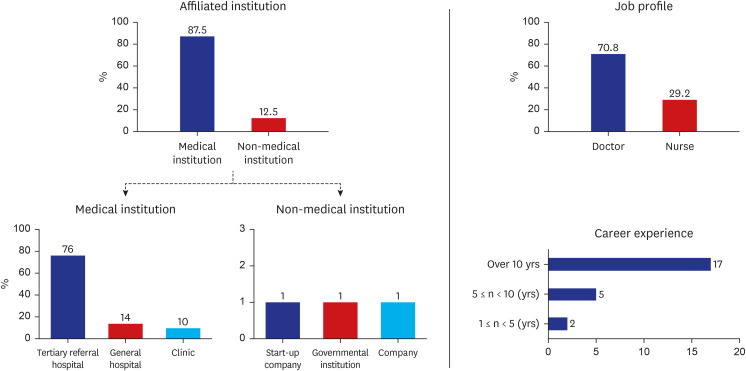

18 In this study, the survey questions were based on current research and information obtained from expert interviews. The questionnaires were administered via e-mail to 26 healthcare providers (doctors and nurses) with clinical experience. The respondents’ perceptions or competencies regarding patient education differed depending on their respective clinical fields or level of clinical experience.

19 To achieve unbiased results, we selected specialists from various clinical fields, including cardiology, hematology, geriatrics, psychiatry, radiology, surgery, pediatrics, emergency medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pathology, plastic surgery, and otolaryngology, as respondents. According to Delbecq et al.,

20 if the backgrounds of respondents of a Delphi survey are homogeneous, 10 to 15 respondents are sufficient for analysis. Moreover, Witkin et al.

21 noted that the approximate size of a Delphi panel should generally comprise less than 50 participants. Furthermore, Hsu and Sandford stated,

22

“If the sample size of a Delphi study is too small, these subjects may not be considered as having provided a representative pooling of judgments regarding the target issue. If the sample size is too large, the drawbacks inherent within the Delphi technique such as potentially low response rates and the obligation of large blocks of time by the respondents and the researcher(s); can be the result.”

Considering the results of previous studies, we concluded that between 10 and 50 respondents would be appropriate for our survey. Therefore, we selected 26 survey respondents.

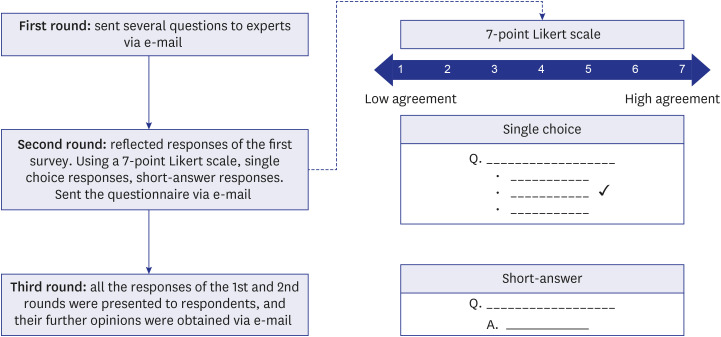

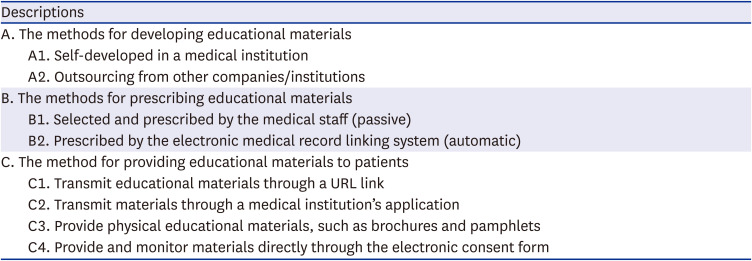

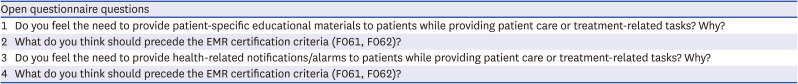

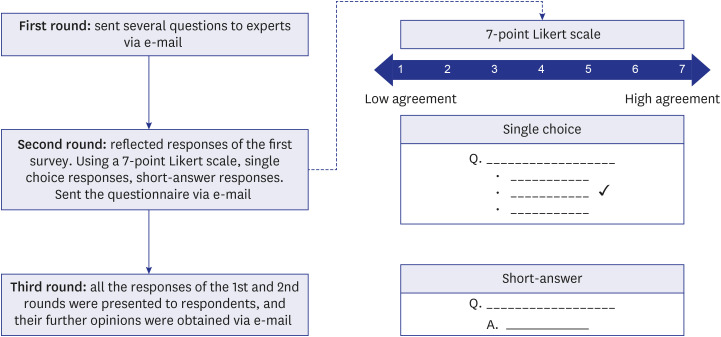

The three Delphi surveys were conducted via email. The first survey was administered as a questionnaire comprising four open-ended questions wherein the respondents were asked about the necessity for PEMs and health-related notifications/alarms (HNAs) and the prerequisites for their implementation. The second survey was a structured questionnaire comprising questions about the respondents’ basic information, such as their affiliated institution, occupation, and career experience. Additionally, we included information on PEM-related certification items and posed seven questions about conditions required for the effective provision of PEMs to patients, preferred delivery methods if PEMs are provided via an EMR system, as well as the prerequisites and appropriate fees for PEMs. Furthermore, we provided information on the certification items related to HNAs and posed six questions about the conditions required for the effective provision of HNAs to patients, preferred delivery methods if HNAs are provided via EMRs, and the prerequisites and appropriate fees for HNAs. Each survey question could be answered on a seven-point Likert scale, through the provision of short answers, or through multiple-choice responses (single selection). In the third survey, after the results of the first and second surveys were presented, the respondents answered questions regarding their additional, comprehensive opinions (

Fig. 1). The survey questionnaires are provided in

Supplementary Data 1.

Fig. 1

Delphi survey process with response methods.

Data analysis

In this study, each interview transcript was read by the researchers several times for accuracy. To prevent expert opinions from being interpreted and reported contrary to their intended meaning, each expert was asked to review their responses twice. The expert interviews were conducted in Korean, and the interviewees were asked to confirm the reports of their responses to the interview questions.

In this study, expert interviews were not conducted for analysis but rather to obtain advice from subject experts. Therefore, rather than analyzing the contents of the expert interviews, we sought to obtain specific consultation criteria. Specifically, the criteria represent meaningful expert insights that were used to develop the questionnaires for the Delphi surveys.

Subsequently, among the three surveys conducted, we calculated the statistical results for the second questionnaire. For responses that used a seven-point Likert, wherein 1 represents the lowest agreement level and 7 represents the highest agreement level, we calculated the average and standard deviation and ranked the results according to their value. Additionally, we determined the total range of all responses and calculated the average of the responses regarding fees. Finally, we ranked the responses to multiple-choice questions using the statistics of the response values and calculating their respective percentages.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center, Korea (IRB 2021-1757). Respondents were assured anonymity and confidentiality, and web-based informed consent was obtained before the online survey.

DISCUSSION

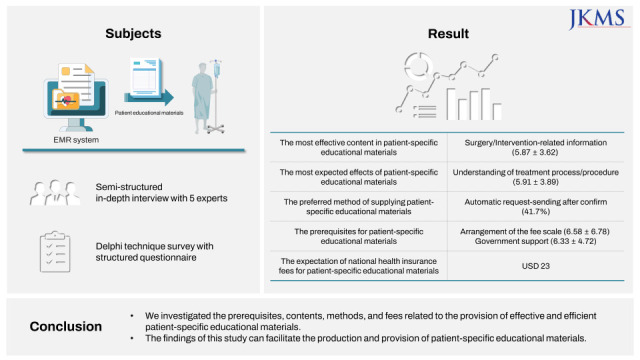

In this study, we assessed effective strategies to help produce and provide PEMs, especially through EMR. We identified the conditions required for the effective provision of PEMs. The most effective content in PEMs was classified based on “surgery/intervention-related information” and “diagnosis/disease-related information.” The important expected effects were “understanding of treatment process/procedure” and “beware of contraindications related to disease/treatment.” These results differed from experts' opinions that suggested “patient’s behavioral changes” and “caution against contraindications” as priorities. To narrow this gap and develop an effective best practice, continuous and active communication with related experts and field healthcare providers is necessary.

The method of sending PEMs after confirmation by healthcare providers according to the automatic request for educational materials/notification through the system was preferred (41%). This preference is due to the expectation that the automated request for educational materials/notifications will reduce the additional burden on the healthcare providers and concerns about the accuracy of providing materials through the system.

Per the expert interview responses, one institution used the automatic prescription system. Currently, most clinicians spend more time manually prescribing educational materials using electronic health records (EHRs) rather than interacting with patients.

24 According to previous studies, the average clinician consultation time was 3.7 ± 3.3 min in Hwang’s study,

25 2.3 ± 0.7 min in Aharonson-Daniel et al.,

26 6.7 ± 8.6 min in Park’s study,

27 and 4.2 ± 2.7 min in work by Lee et al.

28 Focusing on domestic research, the average treatment time is 4.9 min. During this relatively short period, it takes more time for physicians to fill out patient charts using the EHR system than using paper charts.

29 Additionally, a recent study reported that family medicine physicians spend almost half (4.5 hours) of their work hours filling EHR.

30 Several studies have reported that using the EHR system increases a physician’s workload and ultimately causes burnout.

31323334 It would be burdensome for clinicians to prescribe educational materials suitable for each patient's clinical situation within the treatment hours. PEMs, automatically prescribed through the EMR system, could relieve this burden. The automatic prescription function of the system must be expanded and developed to increase system accuracy.

In this study, the most necessary basis for providing PEMs was the “arrangement of the fee scale” and “government support.” Experts agreed that material tailored to the patient’s health literacy level should be provided, and their degree of understanding should be confirmed. It is appropriate to set the fee according to “the number of cases provided educational materials (50%). The different results of the prerequisites for providing educational materials and the fee-setting criteria are due to the burden of developing additional systems to evaluate health literacy, patient understanding, and additional human resources.

We found that most medical institutions did not have a system for further monitoring the patients after educational materials were provided. When the government establishes a feedback system for providing educational materials in the future, a monitoring system should be established for quality management and confirmation. For example, a medical institution using electronic consent forms can be an efficient way to manage information on patient feedback.

The average response of the appropriate fee for PEM was KRW 27,547 (range: KRW 700–100,000, approximately USD 23), and for HNA was KRW 22,014 (range: KRW 100–100,000, approximately USD 18.4). When considering resources for providing PEMs, a cost higher than that of HNAs should be set. However, regarding the responses related to PEM fees, we found meaningful response differences between the doctors and nurses. The average response of doctors regarding a PEM fee was KRW 32,300 (approximately USD 27), while the nurses proposed a fee of KRW 7,814 (approximately USD 6.5). Additionally, the average response of doctors to a fee for HNAs was KRW 25,353 (approximately USD 21), while that of nurses was KRW 7,042 (approximately USD 5.9). This difference can be attributed to the opinion that insurers should pay for patient education and that PEM system updates and developments should be included within the scope of payment, as previously mentioned during the expert interviews.

The average fees determined in these surveys coincide with the fees determined by pilot projects conducted by the Korean government. In 2018, a pilot project for the provision of management education counseling before and after surgery was conducted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. An amount of KRW 25,300 (approximately USD 21, i.e., 20% of the patient’s burden rate) was established as the fee for educational counseling per patient by disease.

35 This fee was applied in practice in 2020, and it is similar to the current guideline fees for patient education, considering the system preparation and human resources involved in the provision of PEMs.

The study findings are subject to the following limitations. First, this study does not consider the needs of the patients who receive educational materials since the surveys in this study were conducted on healthcare providers. More effective and satisfactory PEMs can be developed if additional research is conducted, considering the patient's perspective. Second, further studies involving larger sample sizes are needed to draw a firm conclusion. Thus, future research should use a larger sample size since that of the current study only surveyed a limited number of people (n = 31). Lastly, although we recruited experts from various specialties, the possibility of bias in selecting participants for the expert interviews cannot be completely excluded.

We drew four major conclusions from the findings of this study.

First, to provide effective PEMs, the accuracy or relevance of the context-based material that will be provided to the patient is important. Therefore, a specific follow-up study is required to determine the accuracy and relevance of PEMs in a clinical context.

Second, for PEMs to be distributed automatically through an EMR system, it is necessary to supplement it with a non-interruptive system that does not interfere with existing workflows and to obtain healthcare providers’ trust in the system. Thus, future research must be conducted to determine how user trust and coordination in the PEM delivery system can be obtained to avoid interference with existing workflows.

Third, when developing PEMs, the following two conditions must be considered: 1) clinical processes, such as diagnosis, surgery, and medication, and 2) the patient’s health literacy level. Thus, further research is required into the method by which an EMR system can reflect both a patient’s medical condition and their health literacy level and the effectiveness of this method.

Lastly, a specific system is needed to specify how the government will compensate medical institutions that provide PEMs. Based on this policy support method, we focused on how to provide incentives to medical institutions. Further pilot projects must be performed to improve patient health and ultimately achieve national-level health effects.

Overall, the provision of PEMs can be summarized as a national- and institutional-level task. At the national level, a foundation must be developed for the widespread expansion and dissemination of context-based PEMs. At the institutional level, such as in medical institutions, it is necessary to design and operate PEM systems actively. Thus, additional research regarding the effects of PEMs is required.

The findings of this study provide support for the effective education of patients and medical staff by facilitating the quality control of newly produced PEMs beyond those previously produced without appropriate standards and by selecting the type of PEMs that should be provided according to the patient’s clinical context, reflecting the opinions of medical professionals with clinical experience.

The results of this study can help small clinics, governmental bodies, policymakers, and system developers by providing methods by which PEMs can be produced and provided to patients. In addition, the study findings may enhance the production of PEMs in the absence of appropriate standards. Follow-up research is required to gain further insights into effective patient education, focusing on patients, healthcare providers, and the government.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download