INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has lasted over 2 years. As of June 19, 2022, a total of 18,276,552 cumulative confirmed cases have been reported in the Republic of Korea (Korea). Of these, 2,189,362 (11.98%) cases were detected in children aged 0–9 years and 2,393,695 (13.10%) in those aged 10–19 years. Twenty-two and nine cases of death have been reported in children aged 0–9 and 10-19 years, respectively.

1

Compared to the beginning of the pandemic, the proportion of children with confirmed COVID-19 infection has recently increased. It is therefore important to understand the epidemiology of COVID-19 in children. Moreover, further understanding of the clinical features, epidemiology, and immunogenicity of COVID-19 in children is warranted for undertaking appropriate medical and policy measures.

A viral serological assay is a test to confirm the presence of antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The diagnosis of acute infection through a viral nucleic acid amplification test or rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 does not reflect the actual number of infected individuals in the population. Because there are cases of asymptomatic or subclinical-infections. Therefore, a serologic study is indicated to determine how many people are actually infected within the population.

Seroprevalence can be used as evidence to support the strengthening or alleviation of measures such as quarantine or containment, and school closure and attendance decisions. Moreover, it is essential to consider customized quarantine measures according to the target population, as the risk of severe COVID-19 infection and mortality is different in children compared with that in adults.

In the first half of 2021, the nationwide COVID-19 infection-induced antibody seroprevalence estimate in the U.S was 20.6%.

2

Intensive quarantine measures, including aggressive tracing, open public testing, rigorous epidemiologic investigations, and strict isolation have continued since the beginning of the pandemic, resulting in relatively few confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Korea than in other countries. Several seroprevalence studies for SARS-CoV-2, mainly in adult, were evaluated in Korea during this period. The results varied from 0.07% to 1.27%, depending on the population, region, and time of the test.

3456 In a nationwide study conducted by the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) from April 2020 to December 2020, only 5 out of 5,284 people in 17 cities and provinces nationwide tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibody, and the seroprevalence was 0.09%.

3 In another study, 16 out of 4,085 individuals from 13 regions across the country had antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, which equated to a seroprevalence of 0.39%, from September 2020 to December 2020.

6

In May 2020, a study examined 1,500 residual samples at two university hospitals in Seoul. In that study, no children were reactive to the antibody test. Only one adult tested positive (0.07%).

4 From May to July 2020, 7,248 specimens were collected from two university hospitals in Daegu and Chungbuk. Daegu and Chungbuk were classified as an epicenter and non-epicenter, respectively. The seroprevalence was 1.25% in Daegu and 0.83% in Chungbuk. In that study, 489 participants aged 0–19 years were included. Among them, 0.88% (1/114) of children in Daegu and 0.8% (3/375) of children in Chungbuk were positive in the test.

5

Although the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children could be partially estimated from these studies, there is a limitation in fully reflecting the seroprevalence of COVID-19 in Korean children. This study was the first study conducted to determine the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children-aged 0 to 18 in Korea, about one year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic before the era of COVID-19 vaccination.

Go to :

RESULTS

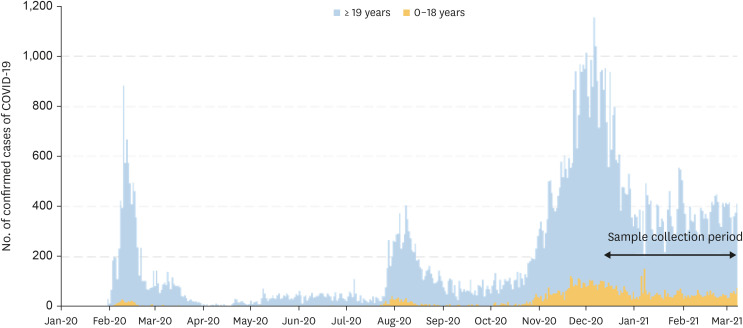

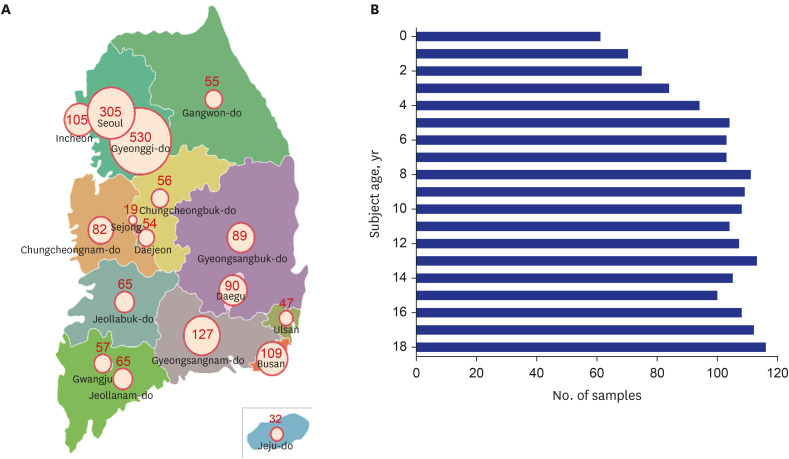

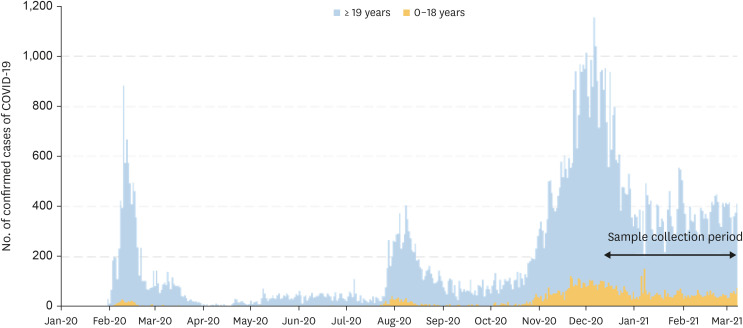

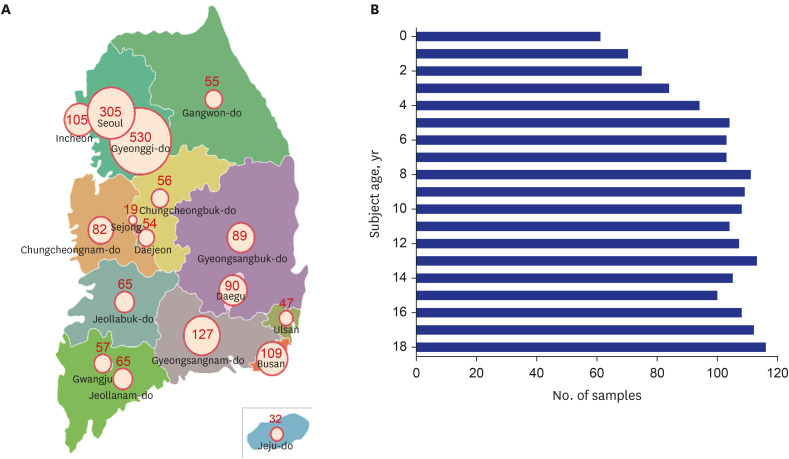

A total of 1,887 residual serum samples were collected from 17 cities and provinces, from December 24, 2020, to March 25, 2021 (

Fig. 1). This period is when the first and second wave of COVID-19 in Korea ended and the third wave was in progress. Based on the national population data provided by Statistics Korea, the highest number of samples was collected from Gyeonggi-do (28.1%, 530/1887). The proportion of samples collected in Seoul was 16.1% (305/1887) (

Fig. 2A). In the age distribution (per one-year interval), the highest number of samples was collected from the 18-year age group (6.1%, 116/1,887), and the least number of samples collected was from infants under the age of 1 year (3.23%, 61/1,887) (

Fig. 2B). Additionally, 44.6% (837/1,887) and 55.4% (1,040/1,887) of the samples were collected from males and females, respectively.

| Fig. 1

Number of daily confirmed cases of COVID-19 as of March 31, 2021. Study samples were collected from December 24, 2020, to March 31, 2021.

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

|

| Fig. 2 Regional and age distribution of study participants. (A) Map of cities and province with number of samples collected. (B) Number of samples stratified by participant age.

|

Of the 1,887 samples collected, 21 samples were collected from provincial medical centers. In Korea, most patients with COVID-19 were cared at provincial medical centers. Thus, samples collected from provincial medical centers were excluded to reduce bias. In total, 1,866 samples were used for laboratory testing.

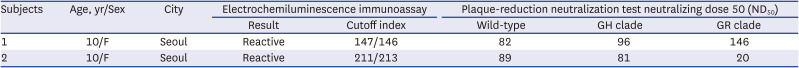

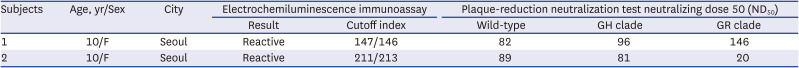

ECLIA testing identified two reactive cases from the 1,866 samples. The positive samples were then re-tested through the same experimental method. Both cases were confirmed as reactive. The resultant seroprevalence was 0.11% (2/1,866). Both reactive samples were collected from 10-year-old females in Seoul in February 2021. When the two samples underwent PRNT testing, neutralizing antibodies were observed (

Table 1). Based on the observed seroprevalence of 0.11%, the number of children aged 0–18 years who are recently infected with SARS-CoV-2 is estimated to be 107.2 per 100,000.

Table 1

Positive reactivity of specimens in the serological test

|

Subjects |

Age, yr/Sex |

City |

Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay |

Plaque-reduction neutralization test neutralizing dose 50 (ND50) |

|

Result |

Cutoff index |

Wild-type |

GH clade |

GR clade |

|

1 |

10/F |

Seoul |

Reactive |

147/146 |

82 |

96 |

146 |

|

2 |

10/F |

Seoul |

Reactive |

211/213 |

89 |

81 |

20 |

Go to :

DISCUSSION

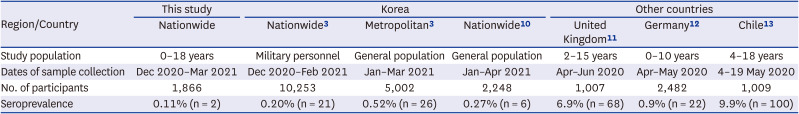

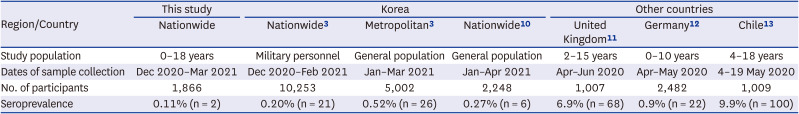

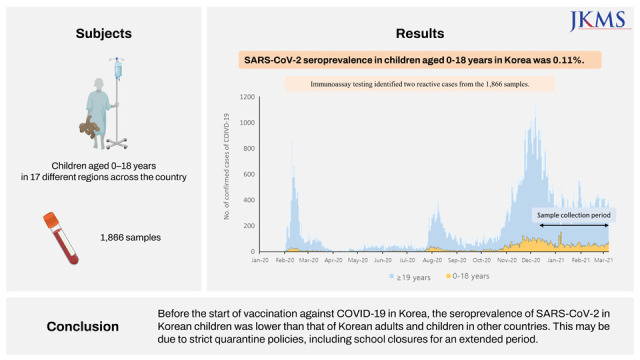

This nationwide cross-sectional study demonstrated a COVID-19 seroprevalence of 0.11% in children aged 0–18 years from December 2020 to March 2021. This seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 is lower than that observed in Korean adult during the similar period (

Table 2).

10111213 Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were assessed among soldiers enlisted in the army, and antibody positive rate was 0.20%. In another study, seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among adults in the metropolitan general population was 0.52%.

3 The SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence of KNHANES in subjects aged 10 years and older was 0.27%.

10 Although some children were included in the KNHANES study, the seroprevalence was lower in the present study.

Table 2

Prevalence of serum antibodies to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in Korea and in children in other countries

|

Region/Country |

This study |

Korea |

Other countries |

|

Nationwide |

Nationwide3

|

Metropolitan3

|

Nationwide10

|

United Kingdom11

|

Germany12

|

Chile13

|

|

Study population |

0–18 years |

Military personnel |

General population |

General population |

2–15 years |

0–10 years |

4–18 years |

|

Dates of sample collection |

Dec 2020–Mar 2021 |

Dec 2020–Feb 2021 |

Jan–Mar 2021 |

Jan–Apr 2021 |

Apr–Jun 2020 |

Apr–May 2020 |

4–19 May 2020 |

|

No. of participants |

1,866 |

10,253 |

5,002 |

2,248 |

1,007 |

2,482 |

1,009 |

|

Seroprevalence |

0.11% (n = 2) |

0.20% (n = 21) |

0.52% (n = 26) |

0.27% (n = 6) |

6.9% (n = 68) |

0.9% (n = 22) |

9.9% (n = 100) |

Currently, it is not known exactly how long antibodies persist after infection with COVID-19. Therefore, the period of infection in participants who tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies cannot be specified in this study. However, from the end of January 2020, when the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported, to March 25, 2021, the study end date, there were 10,356 children aged 0–18 years confirmed with COVID-19 in Korea. The confirmed cases equate to 126.4 per 100,000 people. In the last 6 months before the end of this study, the cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 cases aged 0–18 years old was 9,373, which is 114.4 per 100,000 people of this age.

In this study, the number of people who tested positive for antibodies aged 0–18 per 100,000 was 107.2, which is similar to the cumulative number of cases per 100,000 in the last 6 months. In Korea, a strong mass screening policy continued regardless of the presence of symptoms. Therefore, we speculate that the asymptomatic group would have been less likely to go undiagnosed.

Several studies investigated COVID-19 seroprevalence in children in other countries. In a multi-center cohort study of 1,007 children aged 2 and 15 years from United Kingdom, the SARS-CoV-2 antibody positive rate was 6.9%.

11 In another study conducted in Germany, 2,482 children between the age of 0 and 10 years and their parents were tested. 22 of 2,482 children (0.9%) and 48 of 2,482 parents (1.9%) were seropositive.

12 In Chile, 8–10 weeks after a school-related outbreak, SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing was performed on 1,009 students and faculty members. The antibody positivity rates were 9.9% among the students, which was lower than the 16.6% observed in the adult faculty members

13 (

Table 2). Following many serological studies in various countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted.

14 In one review, 47 studies from 23 countries were analyzed including studies up to August 2020. The SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the general population ranged from 0.37% to 22.1%, with a pooled estimate of 3.38% (95% CI, 3.05–3.72%). In two pediatric studies, the pooled seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 was 8.76% (95% CI, 7.16–10.06). These findings support that SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence is lower in children in Korea than in other countries.

The relatively low seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Korean children compared to children in other countries may be related to the strict national public health and quarantine measures in Korea. This includes closure of school, restrictions on gatherings, and international travel restrictions, leading to subsequent decrease in social activities among children.

46 In 2020, the number of school days in Korea decreased to 50% of that in the previous year. In detail, the number of school days for elementary, middle, and high school students was 48.6%, 46.3%, and 54.8% of that in the previous year.

15 In the first half of 2021, although mean school attendance increased to 73.1%, with 74.6%, 63.8%, and 72.0% in elementary, middle, and high school students, respectively, many students are still unable to attend school due to enforced quarantine measures. According to UNESCO, schools were completely or partially closed for 68 weeks in Korea as of September 2021, which is longer than that in other countries.

16 Additionally, as of May 2021, elementary and middle schools were fully open in two-thirds of OECD countries. However, in Korea, schools were partially open, providing an educational environment with a mix of online and face-to-face classes.

17 As a result, children in Korea have fewer school days early in the pandemic than students in other countries. These situations can negatively affect children, such as reduced learning ability and social skills. These may affect the growth and development of individual children in the short term. In turn, these may increase the burden on society and the nation in the long term.

In this study, neutralizing antibodies were measured using the PRNT method for the two samples that tested positive via the Elecsys

® Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody assay. The ND50 for the S, GH, and GR clades, the SARS-CoV-2 genotypes prevalent in Korea during this study period, were found to be low in both samples. Currently, how long SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are persistent in the body after infection is not clearly known, and the results may vary depending on the test method.

18 Additionally, antibodies are not always generated in every infected patient. In approximately 5–10%, IgG may not be measurable after infection, and neutralizing antibodies may not be detected in those with mild or no symptoms.

1920 Although these findings may explain the low level of neutralizing antibodies in our study, further studies are warranted.

The international standards for binding and neutralizing antibodies are not clearly established. Additionally, the following must be considered: 1) a qualitative assay rather than a quantitative assay was used to measure the binding antibodies, and 2) only two samples were positive in the binding antibody test.

The strength of this study is that it is the first nationwide study to investigate the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children in Korea. Samples were collected in proportion to the population distribution of children by region and age in Korea. However, residual samples were used for analysis, and the risk of bias is possible. In addition, clinical information such as clinical symptoms and confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection was unavailable.

SARS-CoV-2 antibody test is not currently recommended, either to demonstrate the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccination or to confirm the need for vaccination in unvaccinated populations.

21 Therefore, the low antibody positivity rate in children observed in this study should not be used as evidence for recommending vaccination to children.

The low SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in Korean children suggests the following implications. First, children have been adequately protected against COVID-19. The initial quarantine policy of massive testing not only symptomatic cases, but also asymptomatic public and isolating all confirmed patients was effective in reducing serious illness and death. Second, very few children have immunity against SARS-CoV-2 by a year after the pandemic begins. This suggests that most children are susceptible and immunologically naive to SARS-CoV-2. In fact, during the omicron outbreak in Korea, the number of confirmed cases surged, and for about a month from end of February 2022, Korea recorded the highest daily number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the world.

22 As of April 30, at the end of the omicron surge, there were 33,382 cumulative confirmed cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 population in Korea. During this period, more children were infected, and among them, the incidence of COVID-19 per 100,000 population aged 0-9 years and 10-19 years was 55,857 and 48,060, respectively, which was higher than that of adults over 20 years of 19.

23

And as of August 16, 2022, the cumulative number of confirmed cases per 100,000 population was 41,640 in Korea, which is much higher than the United States of America 27,466, United Kingdom 34,342, and Germany, 37,587, the countries with major COVID-19 outbreak.

24

As COVID-19 infection in children shows a milder clinical course and lower fatality rate than in adults, it is necessary to consider different infection control policies for children. In elderly adults with a high fatality rate, active testing, isolation, and vaccination may effectively reduce the burden on the medical system. However, it should be considered in children so they can continue to have educational opportunities and achieve normal development.

This study is a SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence study conducted during the period including the third COVID-19 wave, before the start of vaccination against COVID-19 in Korea. The seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in 1,887 children between the age of 0 and 18 years nationwide was 0.11%, which was lower than that of Korean adults and children in other countries. This may be attributed to strict nationwide quarantine policies, including continuing school closures for a longer period than other countries.

Considering the situation in Korea, where more than half of children are infected with COVID-19, but the fatality rate is very low, strict health and quarantine measures did not appear to be necessary for children. Controlling a pandemic is very difficult, so long-term sustainable methods should be considered. It is unfortunate that children were adversely affected by infection control policies that mainly target adults.

A risk-based control targeting the high-risk group would be one of the strategies.

Vaccination against COVID-19 was introduced in Korea after this study. Thus, follow-up studies must assess changes in seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Korea. The results of this study can be used as data to compare with seroprevalence studies after the Delta and omicron variants outbreaks. And, long-term observation of the health and development of children who are currently experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic is necessary.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download