INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is a rare inflammatory benign breast disease that can clinically and radiologically mimic breast cancer and is difficult to treat due to high recurrence rates despite long-term treatments [

12].

The definitive treatment of IGM is controversial and an optimal treatment strategy has not yet been defined. Conservative treatment, medical or surgical options, or a combination of all treatments are among the strategies described [

34]. The mainstay of surgical treatment is abscess drainage, wound debridement, and larger local excisions, as well as mastectomies. Due to treatment uncertainty and the high rate of recurrence despite all treatments, most authors advocate wide excision as the primary treatment and other treatments as an adjunctive treatment [

23456].

However, a reconstructive approach to the treatment of IGM patients has evolved in recent years from breast-conserving surgery, broadening its general indication to achieve wider excision. With this approach, it is aimed both to control the disease and to preserve the aesthetics of the patient’s breasts [

789]. Furthermore, when compared to patients undergoing simple resections, this technique improves the quality of life and self-esteem [

7]. Therefore, contralateral breast symmetry is considered an intrinsic component of this surgery [

1011]. After starting its use, the authors suggested various definitions and classifications [

111213]. While these techniques allow wide surgical excisions in patients with breast cancer, they also aim to protect the breast. Similarly, many authors have used these new techniques derived from plastic surgery techniques to ensure wide surgical excisions in the surgical management of IGM [

78141516]. Although the term ‘oncoplastic’ in conjunction with the techniques used in the surgical treatment of benign breast disease has created confusion of terms, no author has proposed a new definition. As each new definition deepens the confusion in the literature, some authors have tried to shed light with consensus on the definition and classification of this term [

1718]. However, standardization of these techniques is required to optimize patient selection and improve aesthetic outcomes [

17]. These techniques are defined by the American Society of Thoracic Surgeons as volume displacement, partial mastectomy defect closure, and redistribution of resection volume over the breast, and are classified into 2 levels: level 1 (20%) and level 2 (20%–50%). Volume replacement refers to cases in which volume is added to a partial tissue defect using flaps or implants [

18].

Its etiology, like that of IGM treatment, is unknown, but it is generally thought to be idiopathic. However, some etiological causes have been proposed, including autoimmune diseases, hormonal imbalances, various infections, breast trauma, smoking, and genetic factors [

192021].

After surgical excision or core biopsy, the definitive diagnosis must be confirmed histopathologically, and a differential diagnosis with other granulomatous diseases must be made [

4]. Imaging methods are important for differential diagnosis with malignancy rather than diagnosis.

We present the selection and surgical outcomes of plastic and reconstructive breast surgery techniques used in the surgical management of patients with IGM treated in our general surgery clinic in this study.

Go to :

METHODS

Patient selection

This study was conducted in Gazi Yaşargil Training and Research Hospital with the approval of the hospital’s Ethics Committee (No. 58; July 4, 2022) with the written informed consent. Written informed consent was obtained for the use of all clinical images of the patients.

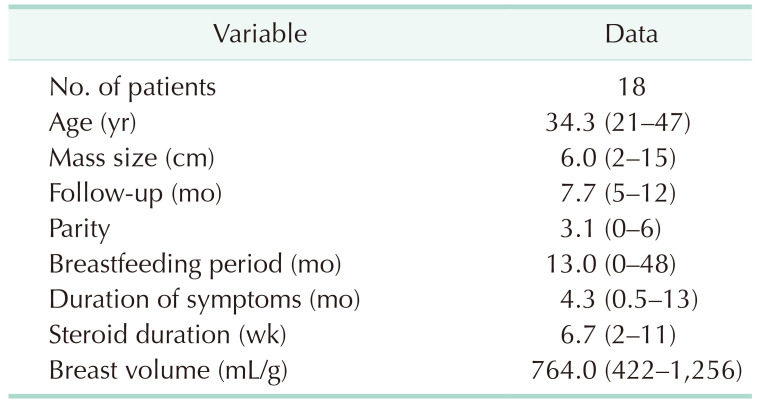

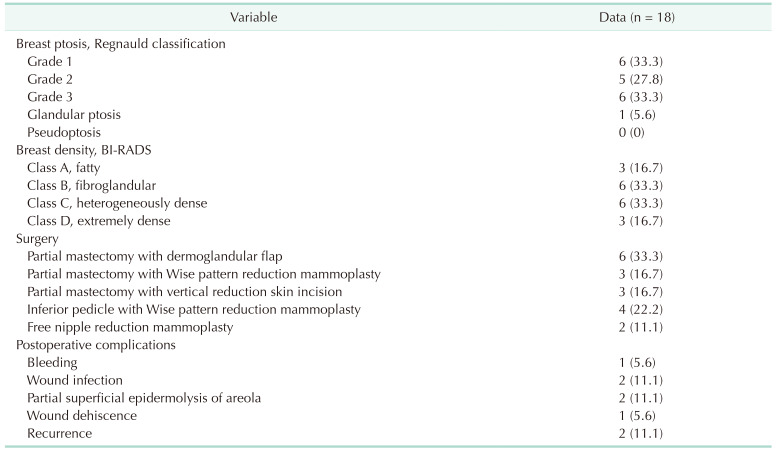

This is a retrospective case series with prospective data collected in a single center over 2 years. The study included 18 patients aged ≥18 years who had been diagnosed with IGM and were operated on with plastic and reconstructive breast surgery techniques between 2020 and 2022. Patients who had other conventional methods of surgery and whose records were missing were excluded from the study. All patients’ basic characteristics were recorded, including age at diagnosis, pregnancy and breastfeeding history, menopause status, duration of symptoms, number of births, breast trauma history, history of autoimmune disease, oral contraceptive use, smoking status, comorbid disease, and family history of breast cancer.

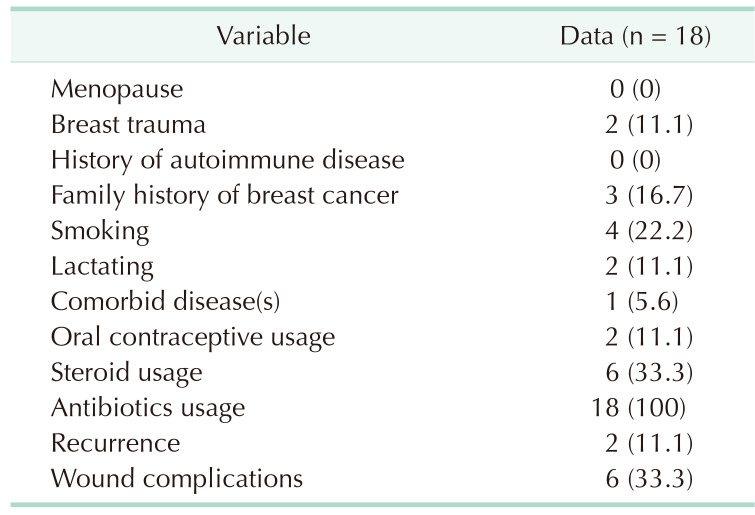

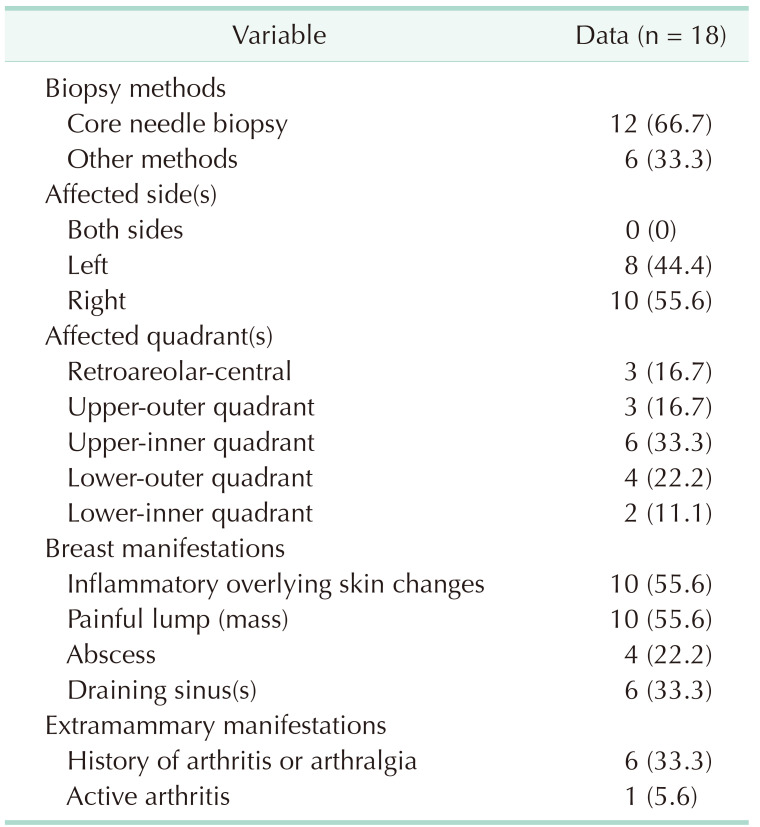

Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of breast lesions, biopsy specimens taken from the abscess wall during surgical drainage, or excisional biopsy of the breast mass were used to confirm the pathological diagnosis. Special stains such as H&E, Ziehl-Neelsen (for tuberculosis), and periodic acid-Schiff were used to stain all pathology preparations (for fungal infection).

The presence of a mass, an abscess, or a fistula, the location of the lesion in the breast, nipple ptosis, nipple involvement, breast volume, and extramammary symptoms were all documented. Mammography and ultrasound were used to assess the extent of the lesion, and MRI was used in patients with multiple or diffuse lesions. Diagnostic studies including culture studies, mammograms, ultrasounds, and histological examinations were performed. After taking the necessary measurements standing up, the breast volumes were calculated using an application called BREAST-V (diepflap. it Medical Software, Rome, Italy) that was installed on an android device [

22]. According to Regnauld classification, breast ptosis was classified into 5 levels: grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, glandular ptosis, and pseudoptosis [

23]. According to the Breast Imaging-Reporting Data System (BI-RADS), breast densities were classified as fatty (A), scattered fibroglandular (B), heterogeneously dense (C) or extremely dense breast tissue (D) [

24]. The patients’ preoperative treatment (antibiotic and steroid use), as well as postoperative complications, follow-up times, and recurrences, were all documented.

In our clinic, primarily medical treatment is applied in patients with IGM. Drainage procedures are performed for patients presenting with abscess clinic and antibiotic treatment is administered to patients presenting with draining sinuses. Surgical treatment is planned due to the inability to treat the disease despite all medical treatments, the side effects of steroids, and the patient’s request. Procedures are delayed till a maximum downsizing of the mass is attained before surgical treatment. However, in cases of non-response to medical treatment or progression, surgical treatment is performed without delay.

Exclusion yielded a preliminary diagnosis of granulomatous mastitis in all 18 cases. All of these patients were on antibiotics, some with steroids, and while they could not cure the disease, they did have to go through multiple drainage procedures. In some patients, recurrence developed after local excision. Medical treatment was given to patients who had microabscesses and drained sinuses in order to reduce them or merge them into a single abscess. In patients who developed a single large abscess, the abscess was excised and drained, followed by extended resection after the lesion contracted.

Plastic and reconstructive breast surgery techniques and the surgical treatment

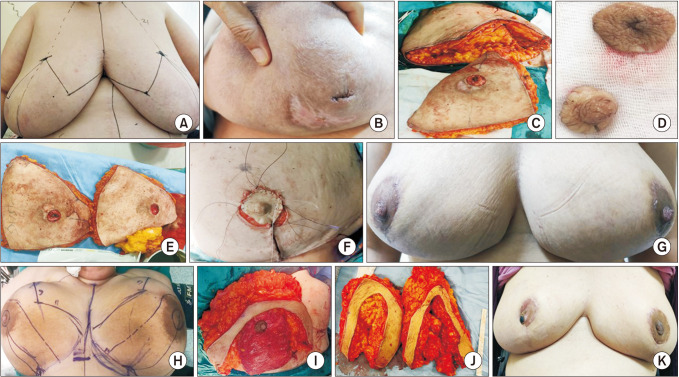

Drawings were created in the correct preoperative evaluation of the patients using anthropometric measurements of the breasts and fixed skeletal points. Breast volume, excision volume, lesion localization, glandular density, presence of fistula, nipple involvement, and breast ptosis degree were all taken into account while drawing the technique to be used. The technique to be used and the results were discussed in detail with the patients. The patients provided the necessary permission for photography and publication, as well as detailed consent for surgery. The drawings made included old scar marks and fistula openings in the skin. Small volume excision techniques such as local tissue rearrangement and crescent mastopexy (level 1) were used on women with medium-sized breasts, small lesions, and grade 1 ptosis. For patients with significant ptosis, adequate breast volume, and larger breasts who desired breast reduction, reduction mammoplasty techniques (level 2) were preferred. Patients with retroareolar lesions underwent free nipple reduction mammoplasty.

We generally preferred partial mastectomy with vertical reduction skin incision (bilateral therapeutic mastopexy) for women who did not want breast reduction but accepted a change in breast shape. We limited the amount of attenuation during level 1 or used one of the level 2 techniques against the high risk of fat necrosis in women with low-density breast tissue with a large fat composition (BI-RADS 1/2) because the resections were performed in a dual plan between the skin and pectoral muscle. Breast reshaping was simple with level I techniques for resections of less than 20% of the breast volume and level 2 techniques for larger resections. In all patients, the simplest cosmetically acceptable techniques were chosen based on the patient’s request.

All operations were performed by the same surgical team under general anesthesia and with routine antibiotic prophylaxis. To remove fistula openings, unhealed wounds, or unsightly scar tissue in the skin, incisions were made in accordance with the preoperative drawings. To avoid canine ear deformity, the incision length was readjusted after repairs. Due to recurrence and failure to achieve total regression, all relevant diseased tissues were extensively excised, including the affected skin, breast abscess, fistula, and inflammatory or necrotic tissues up to the intact tissue limits. Contralateral breast symmetry was performed after determining the amount of tissue resection required for the same side.

The techniques we prefer according to localization are as follows. Superior lesions were treated with a periareolar approach (round block mammoplasty), omega (batwing) mammoplasty, and inferior pedicle mastopexy. In lateral lesions, lateral mammoplasty enabled us to combine wide lesion excision with superomedial nipple-areola complex (NAC) repositioning on a dermoglandular pedicle. In cases of medial lesions, medial mammoplasty or round block mammoplasty was preferred. For lower pole and central subareolar lesions, vertical reduction skin incision and Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty were preferred. Patients with centrally located nipple involvement and adequate breast volume underwent free nipple graft reduction mammoplasty.

Skin flaps were prepared in general, and all relevant tissues were excised up to the lower pectoral muscle. A glandular advancement flap was used to close the defect after parenchymal resection. The pouch was thoroughly washed and aspirated after the NAC was repositioned. The udder was reshaped, and the skin envelope was properly closed to prevent a dog ear from forming. Following wide excisions, a hemovac drain was routinely placed.

After operation, the drains were removed when the drain content decreased below 20 mL. All patients used surgical bras for 1 month. The patients were followed up in terms of early and late complications. Postoperative complications, recurrence, and 6-month follow-up outcomes were all documented.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative variables are represented as mean (range), while categorical variables are represented as number (%).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Although IGM is uncommon, it can clinically and radiologically mimic breast cancer. Diagnosis of IGM is an exclusion; it must be distinguished from carcinoma and inflammatory breast cancer, as well as other chronic inflammatory breast diseases [

4]. The presence of noncaseating granulomatous inflammation was confirmed histopathologically by core biopsy and biopsies taken from the abscess walls of all patients at the diagnosis stage. Since no clear pathogenesis was found in the patients’ anamnesis and etiological studies, all cases were classified as idiopathic.

The optimal management of IGM is still controversial. The purpose of this study was to discuss the selection and outcomes of plastic and reconstructive breast surgery techniques used in the surgical management of patients with IGM. Because of the high recurrence rates, wide excisions remain the primary treatment in the surgical management of IGM [

2456].

Large breasts with >20% excision of breast tissue, inferior or centrally located lesions, and varying degrees of breast ptosis may result in unacceptable cosmetic results [

11]. As a result, plastic and reconstructive breast surgeries have recently evolved into breast-conserving surgery to achieve wider excision. These methods also include contralateral breast symmetry, which incorporates aesthetically derived breast reduction techniques into the field of breast surgery and allows for resection of up to 50% of the breast volume without sacrificing aesthetics [

101112]. The authors used these techniques to manage patients with IGM who needed extensive resection, with acceptable complications, recurrences, and cosmetic outcomes [

7891415].

These techniques in general are level 1 techniques, which include small volume excisions like local tissue rearrangement and crescent mastopexy; while level 2 techniques include larger volume excisions like circumvertical mastopexy designs and reduction mammoplasty designs (including free nipple graft) [

18]. As a result, we used level 1 techniques in 6 of the patients (33.3%) and level 2 techniques in the remaining patients. We generally preferred level 1 techniques in young patients with small-medium chest volume and grade 1 ptosis.

It is critical to identify the elements that can be used to select patients and determine the best technique. The most important factors are undoubtedly excision volume, lesion localization, and glandular density [

11]. Excision of more than 20% of breast tissue necessitates the use of level 2 techniques for acceptable cosmetic results [

1011]. The authors create an atlas of techniques that can be used for lesion localization and make detailed recommendations about the details [

11122526]. Although we used these atlases to select the technique in this study, we mostly discussed individualized surgical selection with the patients.

Level 1 techniques require dual-plane breast dissection from both the skin and the pectoral muscle. With dual-plane attenuation, a dense glandular breast (BI-RADS 3/4) can be easily mobilized without risk of necrosis. Low-density breast tissue with a high fat composition (BI-RADS 1/2) has a higher risk of fat necrosis after intense weight loss; therefore, when deciding on the plastic and reconstructive breast surgery technique to use [

11], mammograms should be used to determine breast density. In our study, the distribution of the patients according to their breast densities was homogeneous.

As a result, patient desire is the most important factor in the selection of the technique, both in terms of patient satisfaction and medicolegal events. We chose a technique based on the patients’ requests for breast reduction for large breasts and mastopexy for severely ptotic breasts.

Although the type and approach of technique vary, the general principle is based on the transposition of intraglandular flaps prepared by releasing the patient’s own breast tissue in the dual plane (skin-muscle) following diseased tissue excision, closing the defect, and recreating an acceptable breast shape. We believe that an individualized surgical approach should be used for effective patient management because the patients in this study were seeking definitive surgery for recurrent IGM despite all treatments. Because there are numerous factors related to the patient and the disease that will influence the scope of the preferred technique, as well as the patient’s desire. Our surgical indications were recurrence after excision in 8 patients (44.4%), recurrence after various drainage procedures due to an abscess in 4 (22.2%) patients, and persistent disease despite medical treatment in the remaining 6 (33.3%).

In the general literature, studies focusing on the surgical treatment of IGM lesions with plastic and reconstructive breast surgery techniques are small case series focusing on patient satisfaction [

71415]. Overall, patient satisfaction was reported to be 77%, with low recurrence and complication rates [

7]. Breast surgeons dealing with plastic and reconstructive breast surgery must balance 2 opposing goals: a cosmetic result aimed at patient satisfaction on the one hand, and a wide resection to prevent recurrence on the other. Otherwise, prolonged excision may leave a large tissue defect that is difficult to close, resulting in a negative cosmetic outcome [

27]. As a result, some authors recommend stage I prosthesis implantation for patients with IGM after conservative treatment for definitive efficacy and high patient satisfaction [

16], or delayed breast reconstruction to monitor surgical recurrence [

28]. We advocate wide excision and reconstruction with simultaneous plastic and reconstructive breast surgery techniques for patients. For extensive disease requiring mastectomy or small breasts requiring >50% resection, we recommend the use of an autologous flap and implant. Assessing the location of the tumor and the associated risk of deformity is an important tool in planning the appropriate surgical approach [

11].

To achieve a good aesthetic result, the variables of the disease and breast tissue should be carefully evaluated when planning a wide resection. If a patient has IGM and has breast ptosis and large breasts, one of the reduction mammoplasty techniques, which usually involve excision of the skin envelope, should be preferred to reduce the breast. Depending on the location of the lesion, the degree of ptosis, the density of the breast, the Wise pattern, or the vertical scar technique, superior, superomedial, or inferior pedicle mammoplasty may be preferred. However, in retroareolar centrally located lesions, free nipple reduction mammoplasty is an option. Excision of the skin envelope, as well as previous scar marks and fistula openings, should be planned as incision preferences.

Following partial mastectomy in the patients included in this study, dermoglandular flap transposition was used (round block technique, batwing mastopexy) in 6 patients (33.3%), Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty was used in 3 patients (16.7%), vertical reduction skin incision was used in 3 patients (16.7%), inferior pedicle with Wise pattern reduction mammoplasty was used in 4 patients (22.2%), and free nipple reduction mammoplasty was used in 2 patients (11.1%).

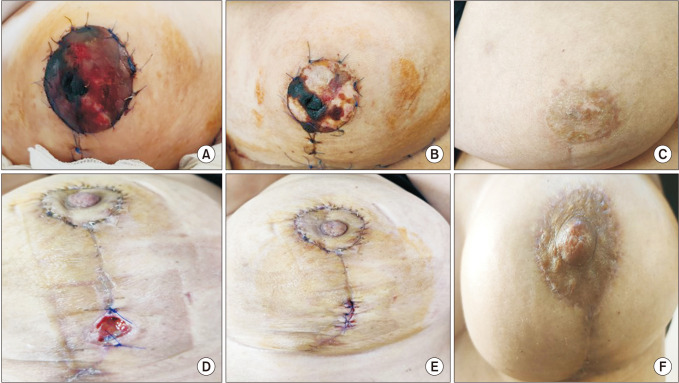

The round block technique involves deepithelialization of the periareolar space with NAC provided by a central glandular pedicle in mildly ptotic, mid-sized breasts with upper pole lesions near the areola. The same technique can be applied to the opposite breast at the same time to achieve symmetry. Another good option for upper quadrant localizations is batwing mastopexy (omega plasty) [

25]. We have successfully applied both techniques to our patients, with low complications and good cosmetic results.

Level 2 techniques were used for wider resections in patients with sufficient volume who also desired breast reduction. However, vertical reduction skin incision (bilateral therapeutic mastopexy) was frequently our preferred procedure for women with ptotic breasts who did not want breast reduction but accepted a change in breast shape. Since it allows for wide excision within the limits of standard marks, this technique is ideal for lower pole tumors and central subareolar tumors. The principle here is that the only way to reduce breast volume is through wide local excision [

25]. Reduction mammoplasty techniques, on the other hand, were preferred for patients who desired breast reduction but had significant ptosis, adequate breast volume, and larger breasts. Depending on where the lesion is located, a preoperative skin pattern and NAC pedicle are designed to allow for wide resection within the resection pattern typical for the specific reduction technique chosen, as well as filling the planned partial mastectomy defect with remaining breast tissue. The contralateral breast is reduced after determining the amount of tissue resection required for the same side [

25]. We preferred the Wise pattern with inferior pedicle reduction mammoplasty technique, which is particularly effective in upper quadrant localizations and advanced ptosis.

Local tissue remodeling and crescent mastopexy, which are important components of many plastic and reconstructive techniques, were performed on women with medium-sized breasts, small lesions, and grade 1 ptosis. These approaches typically involve lifting the skin/subcutaneous flaps to allow mobilization of the underlying glandular tissue to fill the glandular defect [

25].

In addition, due to the negative effects on flap nutrition, we performed operations on 4 active smokers (22.2%) who had quit smoking for 1 month. By using conservative treatment, we were able to postpone the operations of 2 patients (11.1%) during the lactation period until after lactation. We gave antibiotics to all of the patients, despite the fact that no benefit could be demonstrated [

29]. Due to the obvious side effects, we only used steroids on 6 of our patients (33.3%). However, 2 recurrence patients (11.1%) benefited from local steroid injections [

9]. By recommending reduction mammoplasty to 3 patients (16.7%) with large breasts and a family history of breast cancer, we hoped to reduce the risk of breast cancer [

30].

Overall, surgical and patient-reported outcomes were satisfactory. Overall, the surgical and patient-reported outcomes were favorable.

Although the treatment of IGM is controversial, the use of these techniques may have increased the treatment costs. However, patient satisfaction with good cosmetic results plays a primary role in the use of these techniques by surgeons. There is little information about the cost-effectiveness analysis of IGM treatment in the literature. Future studies may enlighten this major issue and contribute to a certain standardization in the management of IGM.

This study has some limitations. For starters, the sample size was small and came from a single location. Second, the follow-up was relatively short. Furthermore, no patient satisfaction survey was conducted.

In conclusion, for patients with IGM who are refractory to conservative treatment or have unsatisfactory results after primary surgery, a surgical management strategy based on the size and location of the lesion should be established. The simplest and most easily applicable techniques can yield successful results with acceptable complication rates in these patients. This study demonstrated that the plastic and reconstructive breast surgery techniques, in conjunction with wide excision, can be used safely in reconstruction in patients with IGM, resulting in low recurrence rates.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download