DISCUSSION

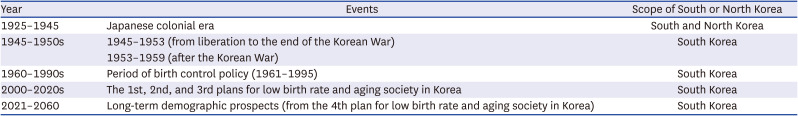

Based on the above results, the changes and trends in the population count, birth rate, and number of births in Korea during the past 100 years, from 1925 to 2020, were examined. In this discussion: 1) using the statistics mentioned above, we examine the changes in the history and events of the relevant past that affected the changes in the birth rate, 2) we review the causes and countermeasures of the low fertility society problem, which is currently emerging as a serious demographic, social, and economic problem in Korea, and 3) we determine the meaning of the statistically predicted estimates up to the year 2065. To explain the relationship between the history and events related to the changes in the fertility rate of Korea, this study divided the modern history of Korea into the following periods: 1) the Korean Empire and Japanese colonial period, 2) period of liberation, 3) Korean War and the late 1950s, 4) period of birth control policy (1961–1995), 5) period of population quality improvement policy (1996–2003), and 6) period of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th plan for an aging society and population (2005–2025).

Looking at the Korean Empire and Imperial Japan’s forced occupation period, in 1897, Emperor Gojong proclaimed the name of Korea as the Korean Empire, and in 1910, the annexation of Korea to Japan began. Statistical data for this era include the national census, the current state census, and the data of the dynamics survey based on reports of births and deaths,

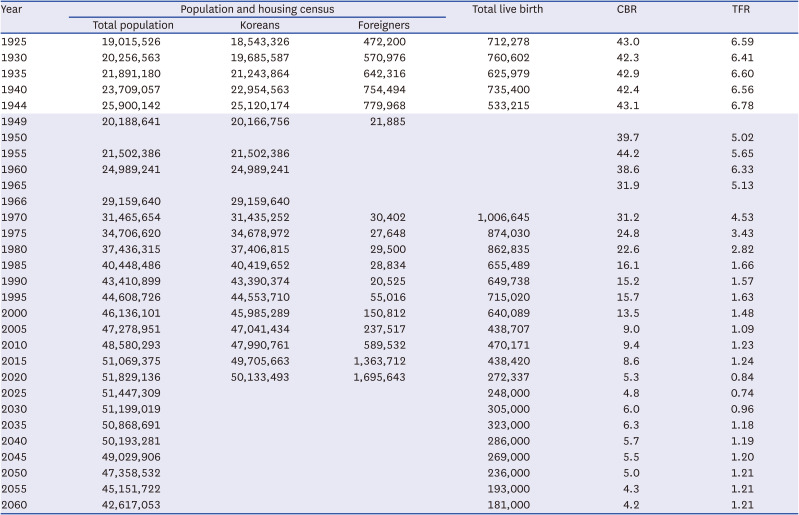

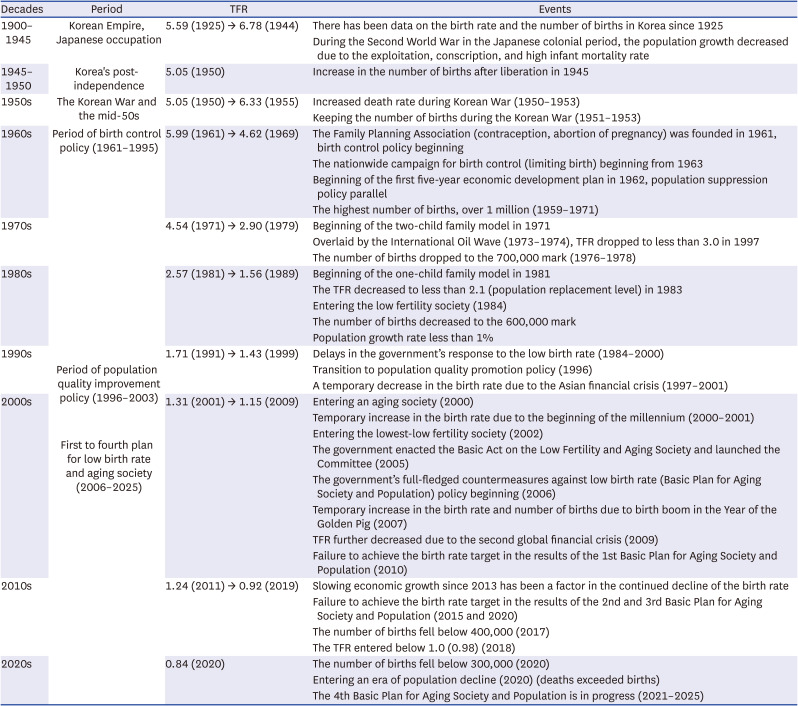

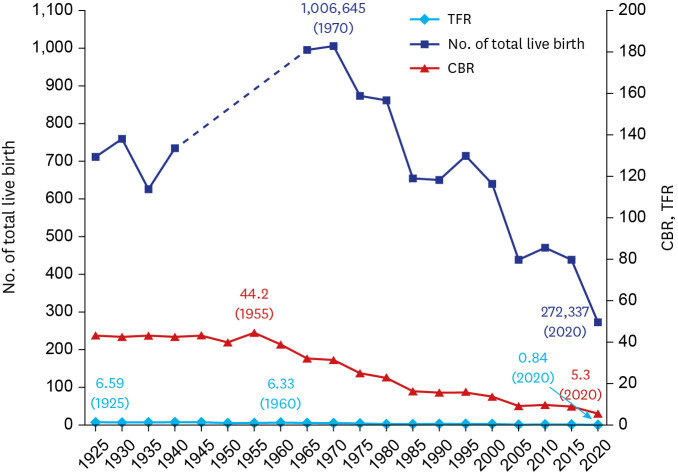

9 most of which were based on estimates. As is usually the case with the colony’s demographics, the current state census was compiled primarily based on a police census. Compared with the year 1925, the total population increased significantly in the 1940s, which may have been due to the initiation of the food rationing system, and the number of undeclared births that were reported all at once. The TFR during the Japanese colonial period was 6.0–7.0, a period when the infant mortality rate was high; as a result, the population growth was negligible. With World War II breaking out in 1939, Japan’s severe exploitation and forced labor at the end of the Japanese colonial period reduced the number of births in Korea from 600,000 to 500,000. With the liberation of Korea in 1945, the number of births increased from 590,000 in 1946 to 630,000–680,000 in 1947–1950. The TFR in 1950 was 5.05. During the Korean War period and the late 1950s, even during the Korean War of 1950–1953, the number of births decreased slightly to 630,000 in 1950 but remained at 670,000–770,000 during 1951–1953. In 1955, the TFR was 6.33, and the population decreased significantly owing to a sharp increase in the death rate during the war. The period from 1961 to 1995 was the period of birth control policy. In 1961, the Korean Family Planning Association was founded, and the birth control policy began. In 1963, a nationwide movement to promote family planning (birth control) projects began. The slogans of 1961 gave birth to moderation, “let’s raise well, have little, raise well,” and in 1966, the three-child movement was set into motion (3.3.35 principle, let’s have three children before the age of 35). In the process of the TFR, which began in 1962, the population growth suppression policy was strongly pursued (this 5-year economic development plan was the 7th and continued until 1996). At that time, the government distributed free contraceptives to public health centers across the country to suppress childbirth. The vasectomy was also free of charge.

While the TFR decreased from 5.99 in 1961 to 4.62 in 1969, the number of births each year was over one million during 1959–1971, and this period recorded the highest number of births in Korean history. In 1971, the two-childbearing movement was launched, and in the mid-to-late 1970s, the birth control policy overlapped with the international oil shock (1973–1974). During 1977–1979, the TFR ranged from 2.99–2.90, entering the second era, and the number of births during 1976–1978 decreased to 700,000.

Family planning (birth control) was continued in the years 1981–1989. In 1981, the slogan raised was “one well-raised daughter out-envies ten sons,” in 1983, the slogan was “two’s too much.” During 1979–1982, the number of births remained in the mid-to-late 800,000 range. In 1983, it entered the population replacement level, defined as less than TFR 2.1. Since 1984, Korea entered an era of low fertility (TFR 1.76), with the number of births decreasing to 600,000, and the population growth rate being < 1%. In 1989, free contraceptive services were stopped, and family planning (birth control) was somewhat relaxed. In the 1990s, although the era of a low fertility society was not yet in full swing, the government abandoned this policy in 1994, 32 years after the birth control policy was introduced. Following this, Korea witnessed a period of “Population Quality Improvement Policy,” which started in 1996 and ended in 2003. During this period, despite the entry into the era of a low fertility society in 1984, until the early 2000s, the government and other social circles were not aware of the seriousness of the low fertility society, and the policy response was delayed due to the inertia of the long-term population suppression policy.

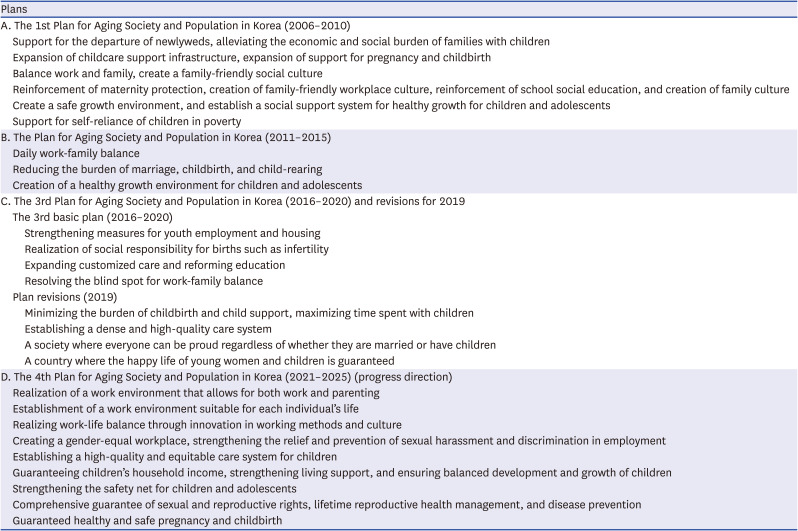

In the 2000s, the TFR rebounded briefly between the years 2000 and 2001, ranging from 1.48 to 1.31, due to the start of the 2000 millennium boom. In 2002, it entered the era of the lowest-low fertility society (TFR less than 1.3) (January 18, 2002). This was the period when Korea’s seriously low fertility society began in earnest. In 2000, the elderly constituted 7.2% of the total population and entered the phase of being an aging society, a critical problem that is demographically second to that of the low fertility society. In the 2000s, there was an increase in infertility, avoidance of marriage, and avoidance of pregnancy. An increase in the age of pregnancy and giving birth emerged as the major cause of low fertility. In 2004, the government set the issue of the low fertility rate in the aging society on the national agenda, after realizing its seriousness. In 2005, the government enacted the Basic Act on the Low Fertility and Aging Society, launched a related committee, and took full-fledged countermeasures for the low fertility society policy. It began with the 1st plan for a low birth rate and an aging society (2006–2010) announced in 2005. Although the TFR (1.26) and the number of births (490,000) increased temporarily due to the birth boom in 2007, the “Year of the Golden Pig,” it was temporary. Although the 1st plan for the aging society and population was implemented with the goal of improving the TFR from 1.08 in 2005 to 1.61 (OECD average) in 2010, it failed to achieve the goals. Korea’s TFR decreased to 1.15 due to the second global financial crisis that occurred in 2009.

The government implemented the 2nd plan for the aging society and population in 2015 with the goal of restoring the TFR to the OECD average in 2016–2030. However, it failed to achieve the target (TFR was 1.24 in 2015). Since 2013, the TFR has continuously decreased, along with a slowdown in global economic growth. Even worse, the number of births declined below 400,000 (350,000) in 2017, and the TFR went below 1.0 (0.98) in 2018.

In the announcement of 2020, the last year of the 3rd plan for the aging society and population, the target was to increase the TFR from 1.21 in 2014 to 1.50 in 2020, however, it failed to achieve this target (TFR 0.84 in 2020). According to the 2020 statistics, the number of births fell below 300,000 (270,000), following the fall of 400,000 in 2017. Korea entered an era of population decline, recording 300,000 deaths in three years. We reached the age of the population cliff.

The government established the 4th Plan for Aging Society and Population in 2021 to shift the goal of resolving the low fertility society from fertility-oriented policies to policies that improve the quality of life of all generations, emphasizing the integration and solidarity of classes and generations, but it did not present specific TFR target figures for 2025.

The causes analyzed in the 1st and 2nd plans for the aging society and population (2005, 2011), which were announced in 2005 and 2010, include an increase in the age of marriage, avoidance of childbirth, delay in marriage and childbirth due to income and employment instability, difficulty in reconciling work and family, lack of childcare system and infrastructure, increase in the burden of raising children, change in values regarding marriage and children, and changes in traditional values, such as family succession. According to the 4th plan for the aging society and population (2021), the causes of a low fertility society were: increased labor market disparities and precarious employment, intensifying competition for employment, intensifying competition for education, single-to-late marriage factors, rise in housing prices, increase in housing costs, decrease in consumer spending capacity, gender discrimination in the labor market, difficulties in work-family balance, increase in dual-income, care gap in the care infrastructure system due to an increase in the demand for care (a situation in which working parents have no place to leave their children after childbirth), decrease in the marriage rate, change in the conception of marriage and family, and changes in the composition of family, which is rapidly progressing. Ultimately, various factors, such as social and institutional factors of employment, childcare, housing, labor, and care; awareness and practice of marriage, pregnancy, and childbirth; aging of women who give birth; and a decrease in the number of births, are complicated. Finding a solution to this problem has emerged as an important task.

Measures and efforts to overcome the above-mentioned lowest-low fertility society were already drafted in the policy implemented in 2006. However, the results were unsatisfactory. Although the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd rounds witnessed the investment of a high budget and the implementation of several measures, the results were a failure. As a result, the following 4th plan was formulated and is currently being implemented.

The direction of the 4th Plan for Aging Society and Population (2021–2025), which is the most recent one, implies the following: 1) change in the basic perspective (focus on improving the quality of life of ‘individuals,’ balanced approach and practice of investment in family support and social structural innovation); 2) guarantee of enjoyment of individual rights in response to aging in the low fertility society (transition to a society where we work together and care for each other, guarantee basic rights to children, ensure there are comprehensive sexual and reproductive rights, and strengthen the medical support for pregnancy and childbirth along the life cycle); and 3) improvement in the nation and society’s ability to respond to demographic changes (reinforcement of education-training and life-based foundations where everyone’s capabilities can be exercised, innovation towards an integrated society in response to the new normal of demographic change, etc.).

To put the policies into practice, the plan attempts to create a society where: people work together and take care of each other (work-life balance enjoyed by all: realization of a work environment that allows work-parenting, establishment of a work environment that harmonizes with an individual’s life/work-life balance through work style, and facilitation of cultural innovation); there is gender-equal working society (creating a gender-equal workplace, strengthening the relief and prevention of sexual harassment and gender discrimination in employment/improving the quality of jobs in the field of intensive care work for women); there is reinforcement of social responsibility for child care (establishing a dense and high-quality care system, creating an equitable primary care environment for children/improving efficiency through the integrated operation of child care, and improving the efficiency through the integrated operation of child care); there is universal guarantee of children’s basic rights (guaranteeing children’s household income and strengthening livelihood support, ensuring the balanced development and growth of children/strengthening the protection and safety net of children and young people); and there is guarantee of lifetime sexual and reproductive rights (comprehensive protection of sexual and reproductive rights, life-long reproductive health management, and disease prevention or healthy and safe pregnancy and childbirth). However, the target TFR value for 2025, when the fourth round ends, is not specifically presented. Thus, the result is noteworthy.

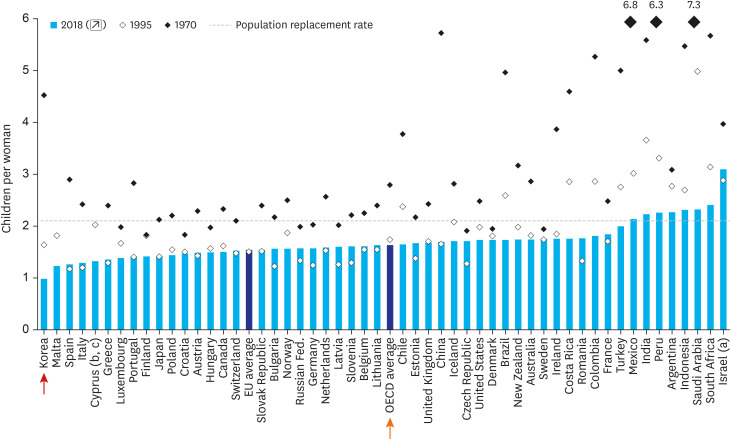

According to the estimated birth rate and number of births until 2065 published by Statistics Korea, Korea’s population is projected to be 51,821,669 in 2021, with it maintained at 51,926,953 in 2030, then beginning to decrease to 51,629,895 in 2035, and further decreasing to 42,837,900 in 2060, which is 40 years from now. The total number of births is estimated to increase from 290,000 in 2021 to 358,000 in 2030, and then gradually decrease to 214,000 by 2060. As per the CBR estimates, there will be a decrease in CBR from 5.6 in 2021 to 5.0 in 2060. According to TFR estimates, TFR is predicted to increase from 0.86 in 2021 to 1.27 in 2060. In both cases, a significant increase was not expected. Looking at the average TFR of OECD countries, TFR decreased from 2.79 in 1970 to 1.74 in 1995, with it standing at 1.63 in 2018. In 2018, Korea had the lowest TFR among the 37 OECD countries (0.98). Among the OECD countries, 11 countries (including Korea) experienced the lowest-low fertility society phenomenon (TFR 1.3 or less). Except for Korea, all other countries escaped the lowest-low fertility society phenomenon. This is the result of comprehensive fertility promotion policies implemented by OECD countries for a long time to restore the fertility rate.

121314 Sweden does not have a special fertility policy. It is simply a family and labor policy within the social welfare system. The society operates on the principle that all people who can work, including women, participate in labor to develop the economy and society. France’s fertility policy is mainly national and public childcare facilities for childcare services, and kindergarten is a free education for most children aged 3 to 5 years. The United States does not have a separate fertility incentive program. Rather, they actively support the cause by aiming for a large family. By sharing resources between generations, extended families have a stronger ability, than nuclear families, to overcome crises in a low fertility population and aging society. Large families who live together can help parents raise children and perform household chores. It seems that most OECD countries that overcame low fertility were able to do so because they eventually created an environment where women could work. In Germany, although women’s participation in the labor market is not an important policy target, childcare services are highly developed. Looking at the countries that have made some progress in overcoming the low fertility rate, we can see that marriage, pregnancy, childbirth, and childrearing are things that individuals and families have to go through, but society and the state are putting their highest priority on all policies and are earnestly implementing these policies. To this end, a gender-equal family policy, work-family balance, and acceptance of various family types without discrimination should be implemented. In addition, policy support is needed to create a virtuous cycle structure, such as the influx of excellent immigrants to secure a workforce, the use of the elderly workforce, and support for the stable economic independence of the youth.

Therefore, in conclusion, looking at the changes and trends in the number of births, fertility rate, and birth rate in Korea over the past 100 years, following the liberation, Korea (South Korea) went through a birth control policy period of limiting childbirth due to the increase in the number of births. When it comes to the population quality improvement policy period, Korea’s low fertility society era that started in the mid-2000s, the TFR fell below 0.84 in 2020. Following the population collapse of 400,000 in 2017, with fewer than 300,000 births (270,000), the number of deaths reached 300,000, thereby entering an era of population decline. In other words, we reached the age of the population cliff. Furthermore, OECD countries recorded the lowest fertility rates. As we enter the era of population decline, we are in a serious situation that will give rise to various socio-economic problems, ranging from demographic problems to future population decline. To overcome this, the government has devised various measures. Thus, the authors hope that this data will help provide basic materials for practical applications in related fields, including medical fields, such as neonate perinatal, infant, and neonatal medicine, and help tackle the low fertility rate problem prevailing in Korea.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download