Abstract

Purpose

Our study aimed to make a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis on the clinical application of gastric-jejunum pouch anastomosis (GJPA) and Billroth-II anastomosis after distal gastrectomy.

Methods

We collected clinical data from 249 patients who received distal gastrectomy from January 2016 to July 2020. According to the reconstruction method used, all patients were divided into the Billroth-II group and the GJPA group. Clinical data and operation complications were analyzed.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the 2 groups were comparable after PSM. In the Billroth-II group, the incidence rate of delayed gastric emptying was higher than that in the GJPA group. Fewer patients suffered reflux gastritis in the GJPA group. The RGB (residue, gastritis, and bile) scores related to the severity of bile reflux into the remnant stomach, gastritis, and residue were higher in the Billroth-II group. Postoperative nutritional status and Visick classification demonstrated that postoperative subjective feelings in the GJPA group were improved significantly.

Currently, stomach cancer is one of the most common tumors of the digestive tract [1]. The mortality of gastric cancer is only inferior to lung cancer, ranking second in China [2]. In most patients with gastric cancer, cancer affects the distal part of the stomach in China, and the only possible cure for gastric cancer is radical distal gastrectomy [3]. Different reconstruction methods affect the safety of operation and the life quality of postoperative patients [45]. Therefore, it is important to explore a safe and easy reconstruction method to apply in distal gastrectomy. In the past, we mainly used Billroth-II anastomosis for reconstruction after distal gastrectomy, because Billroth-II reconstruction does not consider the location of gastric cancer and is simple to operate [6]. However, Billroth-II reconstruction alters the normal gastrointestinal anatomy and can lead to complications related to gastrointestinal reconstruction. Therefore, we invented a new reconstruction method: Gastric-jejunum pouch side-to-end anastomosis (GJPA) [7]. The purpose of this study was to analyze the clinical propensity of GJPA and conventional Billroth-II anastomosis after distal gastrectomy to determine which reconstruction method is optimal.

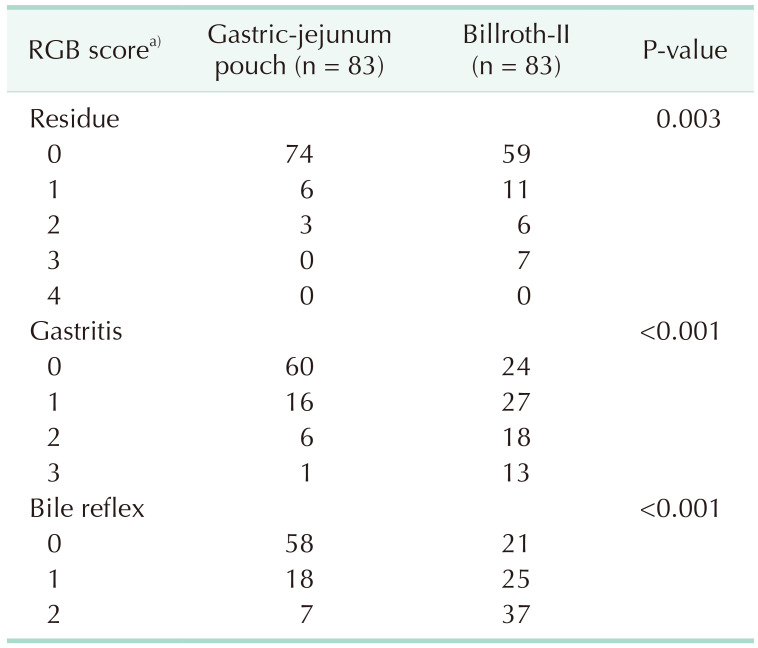

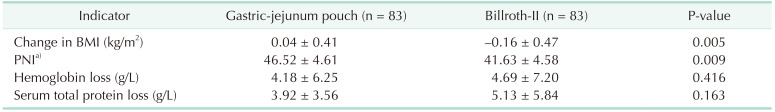

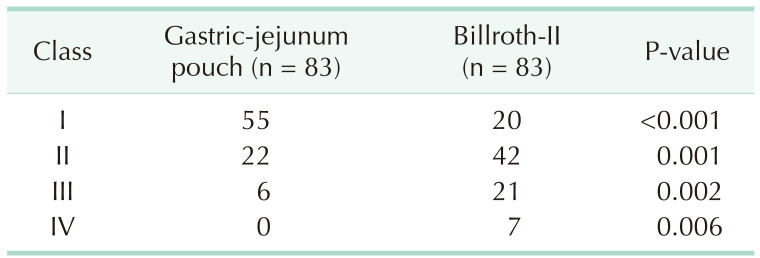

A total of 377 patients with distal gastric cancer were treated in our hospital from January 2016 to July 2020. All enrolled patients must meet the following requirements: first, patients with distal gastric cancer were confirmed by preoperative endoscopy, pathology, and CT; second, the TNM stage of the patients was T2-4N0-3M0, corresponding to stage Ib–III [8]; no distant metastasis and no adjacent organ invasion confirmed by intraoperative examination. We then excluded the following patients: first, patients who did not complete follow-up; second, patients who underwent emergency gastric surgery; and third, patients who had previous experience with upper abdominal surgery. At last, a total of 249 patients met the above inclusion criteria. The enrolled patients were divided into the GJPA group (n = 136) and the Billroth-II group (n = 113) according to the different reconstruction methods performed by the surgeon. One year after the operation, the patients underwent CT, upper digestive tract endoscopy, and routine blood tests. We evaluated the endoscopic changes of the residual stomach according to the RGB (residue, gastritis, and bile) grading system [9]. Furthermore, we used the Visick grading method to assess the postoperative subjective feelings and postoperative nutritional status of the patients in the 2 groups [10]. All patients were reexamined 1 year after the operation. We collected and analyzed the clinical data of all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1 year after surgery. The ethics committee of The General Hospital of Western Theater Command approved the ethical statement of this retrospective study (No. 17015). Written consent was obtained from the patient.

Distal gastrectomy and D2 radical excision were performed according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Treatment Protocol.

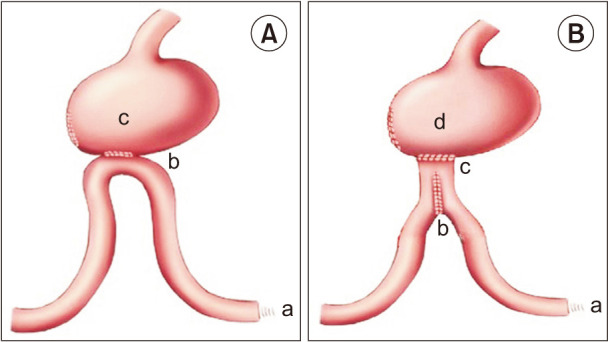

As we previously described [7], Billroth-II anastomosis was performed as follows (Fig. 1A): first, we brought up a loop of jejunum 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz to the residual stomach in an antecolic fashion. Second, we used an electric knife to make an approximately 2-cm longitudinal incision at the antimesenteric side of the jejunum, which was 15 cm away from the ligament of Treitz to bury the circular stapler’s anvil (SDH29, Johnson & Johnson Company, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). The corresponding main part of the stapler was put into the proximal gastric remnant and was matched with the circular stapler’s anvil. Then, we constructed the anastomosis over the posterior wall of the stomach. Finally, the incision of the residual stomach was closed.

GJPA was performed as previously described [7]: (Fig. 1B) first, we brought up a loop of jejunum 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz to the residual stomach in an antecolic fashion. Second, we used an electric knife to make an approximately 2-cm longitudinal incision at the antimesenteric side of the jejunum, which was 15 cm away from the ligament of Treitz. Third, we injected the 2 arms of a 75 mm linear stapler (TLC75, Johnson & Johnson Company, USA) into the afferent and efferent loops of jejunum. The side-to-side anastomosis was performed at the antimesenteric side of the jejunum to construct a jejunal pouch. We then buried the circular stapler’s anvil (SDH29, Johnson & Johnson Company, USA) into the jejunal pouch through the 2-cm longitudinal incision. The corresponding main part of the stapler was put into the proximal gastric remnant and was matched with the circular stapler’s anvil. We constructed the anastomosis over the posterior wall of the stomach. Finally, the incision of the residual stomach was closed.

Statistical processing was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). In this retrospective study, we used propensity score matching (PSM) to equalize the covariates to reduce the selection error among the covariates. PSM matched each patient in the Billroth-II group to a patient in the GJPA group based on preoperative characteristics, including sex, age, pathological stage, and location of the tumor. Following that, the normality of our clinical data was determined by performing Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. The form of median and interquartile range was used to express non-normally distributed data. The form of mean ± standard deviation was used to express normally distributed data. We performed the Mann-Whitney test to analyze the skewed data and used Student t-test to analyze the normally distributed data. The proportion variable was analyzed using a chi-square test or Fisher exact test. It was considered statistically significant when P-value was less than 0.05.

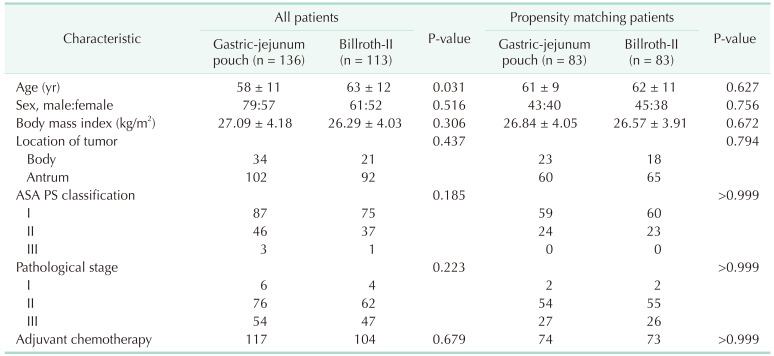

The preoperative clinical characteristics of the patients enrolled in this study were shown in Table 1. The patients in the Billroth-II group were older compared with those in the GJPA group before propensity matching. There was no significant intergroup difference in the clinical characteristics after propensity matching.

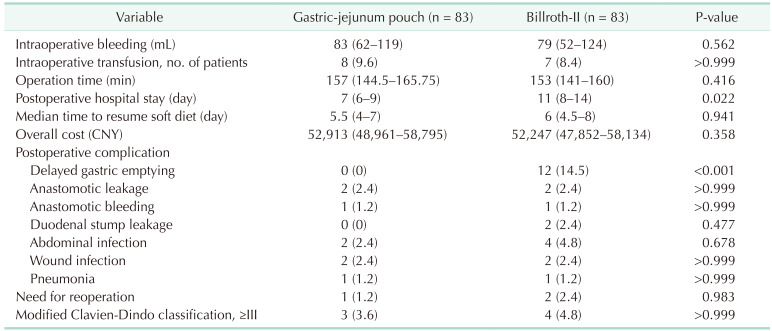

The intraoperative characteristics and early surgical complications of the patients in the 2 groups were shown in Table 2. Compared with the GJPA group, postoperative hospital stay in the Billroth-II group was significantly longer. The incidence rate of delayed gastric emptying in the Billroth-II group was higher than that in the GJPA group. There were no significant intergroup differences in other indicators.

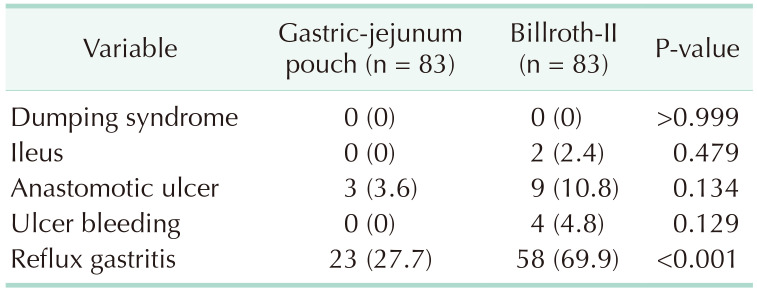

Late outcomes 1 year after operation were shown in Table 3. In the Billroth-II group, more patients suffered from reflux gastritis disease. As shown in Table 4, compared with the Billroth-II group, the RGB scores related to the severity of bile regurgitation into the residual stomach, gastritis and residue were lower in the GJPA group. Significant differences in terms of change in body mass index and prognostic nutritional index were found 1 year after surgery (Table 5). The Visick grading method is a subjective measure of the quality of life of postoperative patients. Compared with the Billroth-II group, postoperative subjective feelings in the GJPA group were much improved (Table 6).

Many surgeons have created a variety of reconstructive techniques after radical gastrectomy to ameliorate the therapeutic outcomes and improve the quality of life of patients with gastric cancer. Gastroduodenostomy (Billroth-I reconstruction) maintains a proper physiological passageway from the stomach to the intestinal tract. However, the retention of gastric remnant size is limited by the location and size of the tumor for patients with gastric cancer, which may increase the incidence of anastomotic leakage due to the high tension of anastomotic stoma. Moreover, many patients lose the chance for reoperation because of the occurrence of gastric stump cancer. For Billroth-II anastomosis, there is no restriction on the size of the residual stomach. Billroth-II anastomosis can completely meet the requirement of radical gastrectomy and become the recommended surgical method for gastrointestinal reconstruction in patients with distal gastric cancer who underwent radical gastrectomy [11]. However, Billroth-II anastomosis changes the normal physiological and anatomical structure of the stomach, leading to significant changes in the route of food in patients after surgery. In addition, Billroth-II anastomosis may disorder the function of gastric remnant regulated by neurohormone and musculogenic factors, resulting in various short-term and long-term postoperative complications [12]. Therefore, a simple, economical, and safe reconstruction can greatly benefit patients undergoing radical gastrectomy. To design a secure reconstruction, our previous study [7] introduced a novel reconstruction: GJPA. GJPA is an adjacent anastomosis between residual stomach and jejunum at the top of a folded jejunum; so, it is a simple side-to-side anastomosis between residual stomach and jejunum. The residual stomach is directly connected with the jejunum pouch after the GJPA is performed. Anastomosis between jejunum and jejunum forms a huge pouch that can allow the digestive juices to flow out of the input loop to reside in it, rather than directly flowing into the residual stomach inducing reflux gastritis. Because there are many similarities between the operation procedure of GJPA and Braun anastomosis, we may regard GJPA as a modified Braun anastomosis. Moreover, GJPA is simpler than Braun anastomosis and is completely different from the traditional Billroth-II anastomosis and Billroth-II with Braun anastomosis. Thus, we think that GJPA should be considered an independent gastrojejunostomy.

In this study, we used PSM to ensure the comparability of baseline characteristics between the 2 groups and reduced any possible bias caused by confounders. Before matching, there was a statistically significant difference in age between the 2 groups of patients. After matching, there was no significant intergroup difference in the clinical characteristics. The intraoperative and early postoperative clinical data showed that GJPA did not increase intraoperative bleeding, did not prolong the operation time, and did not increase the economic burden of the patients. Additionally, compared with the GJPA group, postoperative hospital stay in the Billroth-II group was significantly longer. This may have resulted due to the low incidence of delayed gastric emptying in the GJPA group. In addition, no intergroup difference was found in overall cost. The above results demonstrated that GJPA accelerated the recovery of patients after the operation and that GJPA was economical. The postoperative late outcomes in this study proved that the occurrence rate of late complications (reflux gastritis) in the GJPA group was lower than that in the Billroth-II group. We believe that the high occurrence of postoperative complications in the Billroth-II group is related to a variety of reasons. First, Billroth-II anastomosis is a half-mouth anastomosis. It can prevent gastric emptying from occurring too quickly, but this anastomosis lets digestive juices flow through the loop of input into the stomach first and then into the output loop. Therefore, the residual stomach becomes the path by which digestive juices must be passed through, and the gastric mucosal barrier can be damaged by the digestive juices leading to the occurrence of reflux gastritis [1314]. In addition, GJPA adds a jejunal pouch, facilitating the digestive juices directly entering the output loop, reducing the pressure in the input loop, thus improving the blood supply of the anastomosis, alleviating edema of the anastomosis, and reducing the incidence of delayed gastric emptying, as well as reducing the incidence of reflux gastritis. Finally, as a result of maintaining food amount and reduction of digestive juices reflux, the patients’ residual gastric motility postoperatively recovered quickly, ameliorating their appetite and food intake, preventing body weight loss, and improving the patients’ quality of life.

In this study, we used PSM to eliminate differences and decrease confounding effects between the 2 groups as far as possible; though, in nature, this was still a retrospective study. We cannot ensure that all confounding factors were included in our research. Therefore, to further prove our conclusion, we need to conduct a prospective randomized controlled trial in the future.

In conclusion, GJPA is economical, reliable, and safe for the reconstruction of patients undergoing distal gastrectomy. It deserves widespread promotion in clinical practice.

References

1. Lee S, Lee H, Lee J. Feasibility and safety of totally laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: comparison with early gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2018; 18:152–160. PMID: 29984065.

2. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016; 66:115–132. PMID: 26808342.

3. So JB, Rao J, Wong AS, Chan YH, Pang NQ, Tay AY, et al. Roux-en-Y or Billroth II reconstruction after radical distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018; 267:236–242. PMID: 28383294.

4. Kim JM, Park JH, Jeong SH, Lee YJ, Ju YT, Jeong CY, et al. Relationship between low body mass index and morbidity after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016; 90:207–212. PMID: 27073791.

5. Lee MS, Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, Kim HH, et al. What is the best reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer? Surg Endosc. 2012; 26:1539–1547. PMID: 22179454.

6. Chen S, Chen DW, Chen XJ, Lin YJ, Xiang J, Peng JS. Postoperative complications and nutritional status between uncut Roux-en-Y anastomosis and Billroth II anastomosis after D2 distal gastrectomy: a study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019; 20:428. PMID: 31300019.

7. Cao Y, Gong J, Gan W, Zhou J, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. Gastric-jejunum pouch side-to-end anastomosis: a novel and safe operation of gastrojejunostomy for preventing reflux gastritis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015; 8:5541–5546. PMID: 26131135.

8. Santiago JM, Sasako M, Osorio J. [TNM-7th edition 2009 (UICC/AJCC) and Japanese Classification 2010 in Gastric Cancer: towards simplicity and standardisation in the management of gastric cancer]. Cir Esp. 2011; 89:275–281. Spanish. PMID: 21256476.

9. Nagano H, Ohyama S, Sakamoto Y, Ohta K, Yamaguchi T, Muto T, et al. The endoscopic evaluation of gastritis, gastric remnant residue, and the incidence of secondary cancer after pylorus-preserving and transverse gastrectomies. Gastric Cancer. 2004; 7:54–59. PMID: 15052441.

10. Poziomyck AK, Cavazzola LT, Coelho LJ, Lameu EB, Weston AC, Moreira LF. Nutritional assessment methods as predictors of postoperative mortality in gastric cancer patients submitted to gastrectomy. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2017; 44:482–490. PMID: 29019578.

11. Bove V, Tringali A, Familiari P, Gigante G, Boškoski I, Perri V, et al. ERCP in patients with prior Billroth II gastrectomy: report of 30 years’ experience. Endoscopy. 2015; 47:611–616. PMID: 25730282.

12. Vakhrushev IaM, Ivanov LA. [Changes in gastric secretory function in peptic ulcer patients after gastric resection]. Ter Arkh. 1991; 63:14–16. Russian.

13. Collard JM, Romagnoli R. Roux-en-Y jejunal loop and bile reflux. Am J Surg. 2000; 179:298–303. PMID: 10875990.

14. Montesani C, D’Amato A, Santella S, Pronio A, Giovannini C, Cristaldi M, et al. Billroth I versus Billroth II versus Roux-en-Y after subtotal gastrectomy: prospective [correction of prespective] randomized study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002; 49:1469–1473. PMID: 12239969.

Fig. 1

(A) Billroth-II reconstruction. a, Treitz ligament; b, gastrointestinal anastomosis; and c, residual stomach. (B) Gastric-jejunum pouch anastomosis reconstruction. a, Treitz ligament; b, jejunal pouch (6 cm); c, gastrointestinal anastomosis; and d, residual stomach.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download