INTRODUCTION

Vaccination has been one of the key ways in which the 2-year long coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been addressed. Several types of COVID-19 vaccines were rapidly rolled out and have shown efficacy ranging from 74% to 95% in preventing COVID-19 depending on the vaccine platform.

123

Severe aggravation was also shown to be significantly prevented by the available vaccines.

23 The imperfect efficacy of vaccination has resulted in breakthrough COVID-19 infections and severe progression of COVID-19 regardless of vaccination status, and the factors related to those events are of both scientific and clinical interest. Although the worldwide pandemic situation is largely easing, there is regional imbalance in the severity of the pandemic and in the coverage by vaccines, especially in countries with poor resources. Even in high-income countries, the proportion of unvaccinated individuals is not low. As the world approaches a strategy of living with COVID-19, physicians will frequently find themselves caring for vaccinated and unvaccinated COVID-19 patients and need to be educated for the clinical features of those patients.

Since the first rollout of the AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) vaccine on February 26, 2021, national vaccine coverage in Korea has been favorable, but patients with breakthrough infections have been reported.

45 Although population-based studies estimating the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines have been reported,

678 information about the clinical features and risk factors for aggravation of vaccinated and unvaccinated COVID-19 patients in a real-world setting would be very helpful to physicians. The Korean national COVID-19 policy provided an opportunity to investigate vaccinated and unvaccinated COVID-19 patients needing hospitalization.

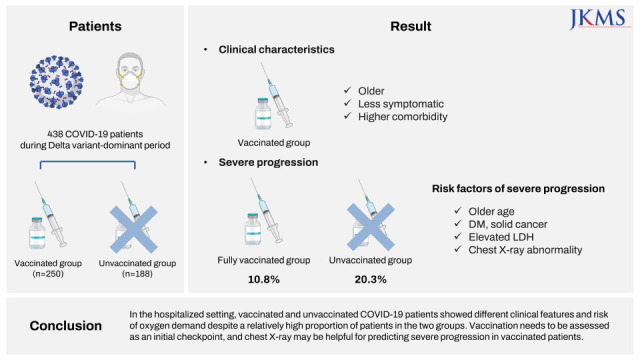

In this study, we aimed to describe how the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 patients present in a real-world in-hospital care setting during the COVID-19 vaccination era and to determine the clinical implications of vaccination status in the individual patient care.

METHODS

Patients and study setting

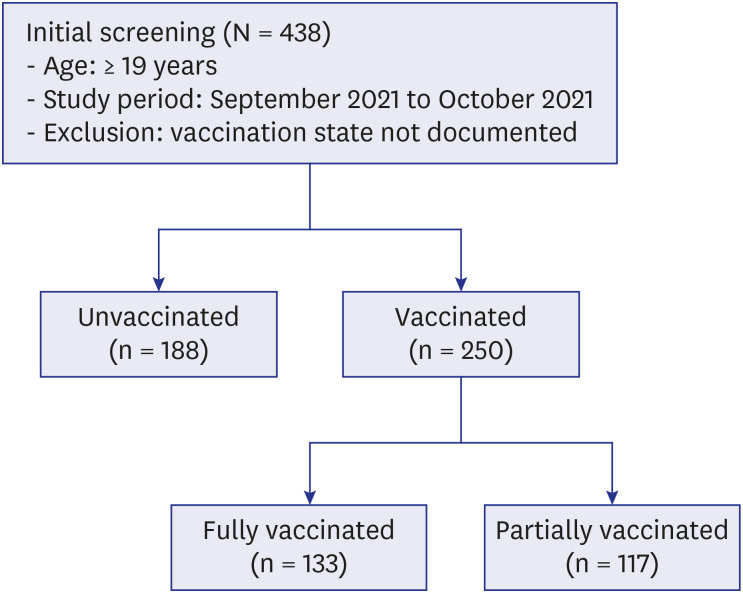

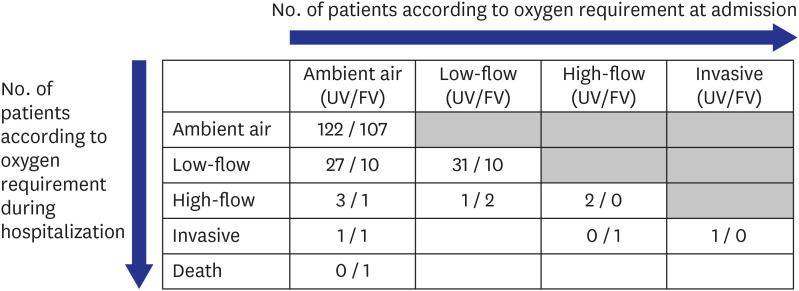

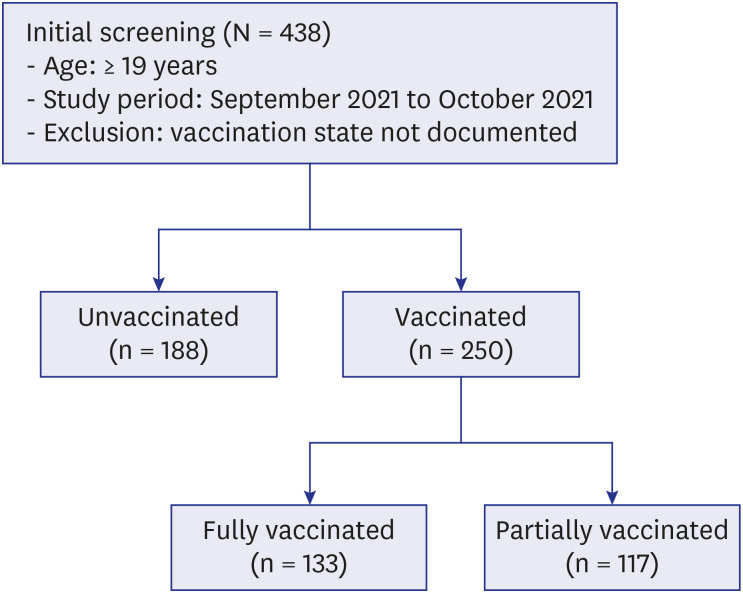

All hospitalized COVID-19 patients ≥ 19 years of age in whom COVID-19 infection was confirmed by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction were enrolled from September to October 2021 at Boramae Medical Center, a university affiliated hospital designated for the care of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Patients for whom information on documented vaccination status was not available were excluded (

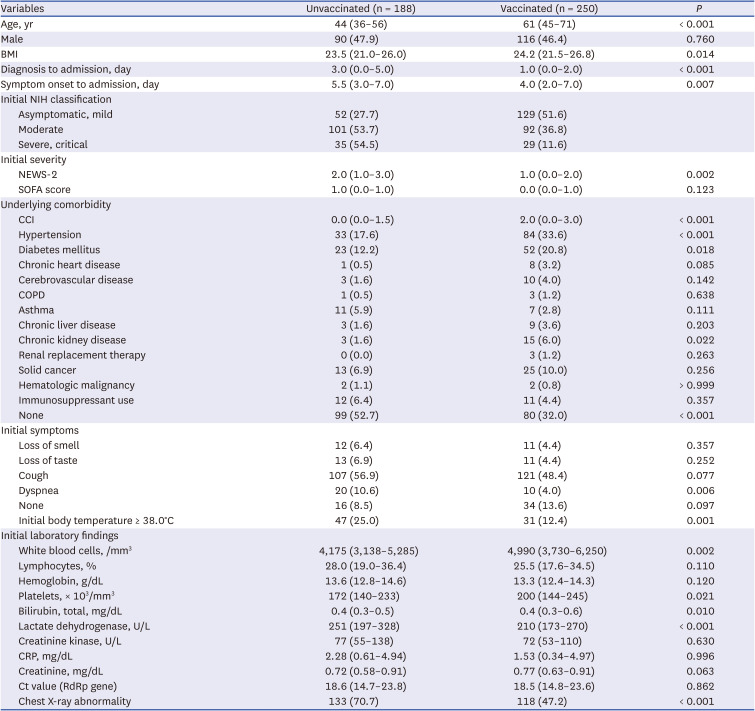

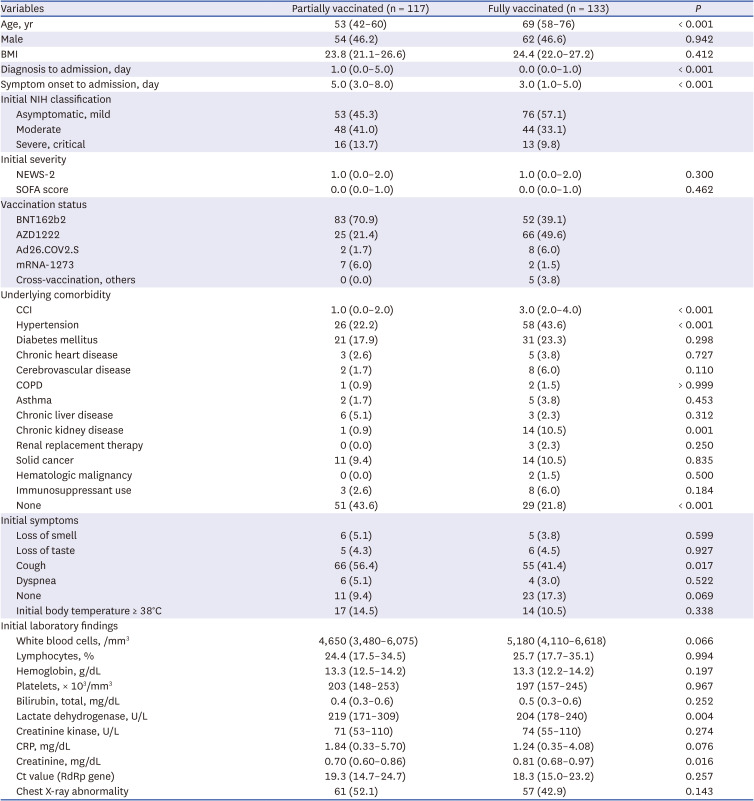

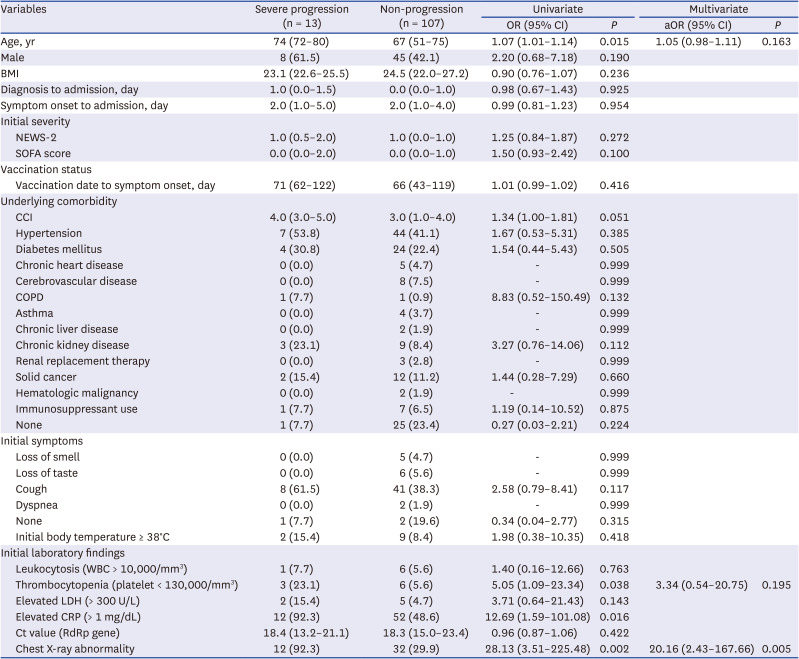

Fig. 1). During the study period, COVID-19 patients classified as belonging to a high-risk group or a symptomatic low-risk group were allowed to be admitted to the hospital. Most other stable COVID-19 patients were isolated in residential treatment centers. The patients were grouped into vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, and their presenting clinical features and the overall risk factors at admission for severe progression were characterized. In the subgroup analysis, clinical predictors for severe progression were assessed in the fully vaccinated group.

Fig. 1

Study setting. A total of 438 patients were enrolled, 188 of whom were unvaccinated and 250 of whom were vaccinated. The vaccinated group was divided into the fully vaccinated group and the partially vaccinated group.

Data collection and definitions

Data were retrospectively collected on demographics, vaccination status, clinical variables at presentation (clinical severity, symptoms and signs, laboratory findings and chest radiography), specific treatments, and clinical outcomes. COVID-19-specific treatments, including the use of remdesivir, monoclonal antibodies, or corticosteroids, and the use of antibacterial agents for periods ≥ 3 days were recorded. The level of oxygen supplementation, the in-hospital mortality, and the duration of hospitalization were used to assess the clinical outcomes.

Initial clinical severity was assessed based on the National Early Warning Score (NEWS)-2 and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score,

9 and the severity of underlying comorbidity was estimated according to the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI).

10 Patients with COVID-19 who had received full vaccination were defined as those who developed symptoms or were diagnosed with COVID-19 more than 14 days after completion the recommended vaccine regimen. Those who were vaccinated at least once but did not meet the criteria for full vaccination were defined as partially vaccinated.

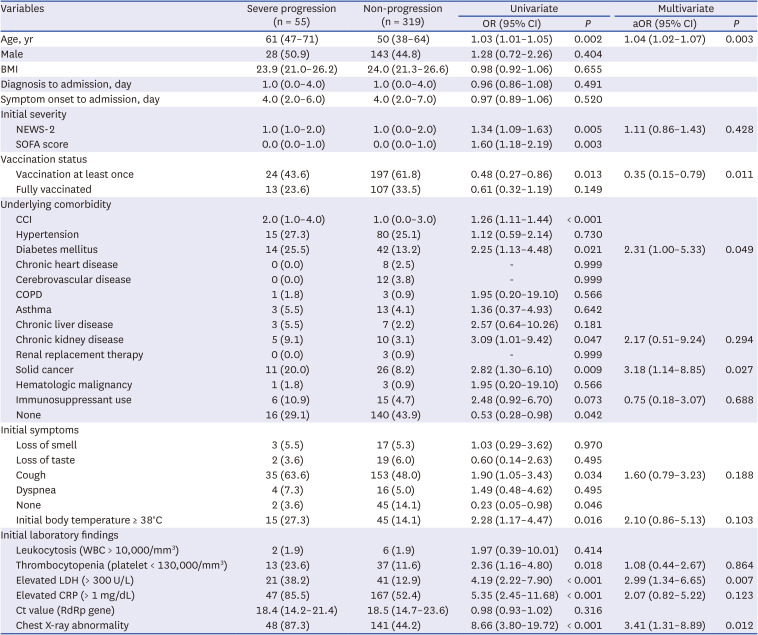

The use of immunosuppressants was defined as having received any anticancer chemotherapy or any immunosuppressive agents, including steroids, within 30 days. The worst results of body temperature on the day of admission and laboratory findings within 24 hours after admission were used. Severe progression was defined as the occurrence of new oxygen demand during the clinical course of the disease, and oxygen demand was defined as needing oxygen for a period of more than 24 consecutive hours. Chest X-ray abnormalities were defined as the presence of lung infiltration suggestive of pneumonia on simple chest X-ray according to the independent formal report of the reviewing radiologists.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. To determine the risk factors for severe progression, multivariable logistic regression was performed using variables for which P < 0.10 in the univariate analysis. To avoid multicollinearity, the CCI, variable of no underlying disease and no initial symptoms were not included in the multivariable model. The SOFA score was excluded from the multivariable model to avoid multicollinearity with the NEWS-2 and thrombocytopenia. To determine the goodness of fit for logistic regression models, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Boramae Medical Center (No. 20-2021-54). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB owing to the retrospective nature of the study. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

DISCUSSION

During the study period, the national policy of Korea was to isolate most COVID-19 patients in residential treatment centers that mainly provided daily living support with minimum medical care for 10 days. Patients with high risk factors for severe progression or complication, or symptomatic patients who required further medical care were admitted or transferred to dedicated hospitals such as our study hospital. In addition, COVID-19 vaccination in Korea was first made available to the high-risk group, which included elderly individuals. Although the percentage of fully vaccinated individuals in the national population ≥ 18 years of age was 54.2%, it differed markedly in different age groups. The percentages of fully vaccinated individuals over 80, 70–79, and 60–69 years of age were 79.8%, 89.6%, and 87.6%, respectively, but among individuals 50–59, 40-49, 30–39, and 18–29 years of age, the percentages were 58.4%, 32.2%, 36.1% and 32.5%, as of 28 September 2021.

Our results showed that the hospitalized COVID-19 patients in our study had characteristics in accordance with the national admission guidelines for COVID-19 patients. The vaccinated patients were older, had more comorbidities and were admitted to the hospital as early as possible in the fear that their condition might worsen. This might result in lower clinical severity at admission among these patients. In contrast, the unvaccinated patients were largely younger, had fewer comorbidities and were admitted to the hospital later in the clinical course of the disease due to severe manifestations that were not prevented by vaccination. We did not intend to compare the individual study subjects, vaccinated and unvaccinated directly; instead, we wanted to describe the type of COVID-19 patients we would expect to see in the hospital after the peak of the pandemic eased down. Although the composition of study subjects can be directly attributed to the national policy for allocation of COVID-19 patients, the scenario may be similar in real-world practice in the near future or might exist in other regions of the globe due to the existence of different policies for pandemic control in different countries.

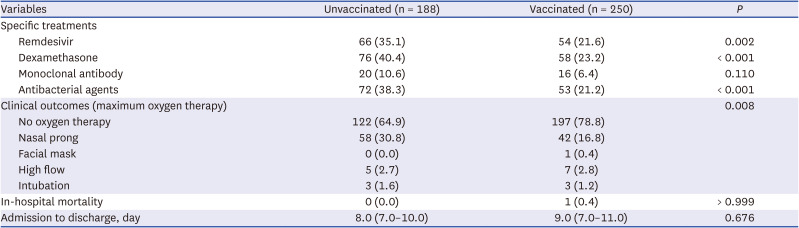

The proportion of patients who required supplemental oxygen was higher in the unvaccinated group than in the vaccinated group. Considering the older age of the vaccinated group and the higher proportion of comorbidities in that group, the fact that a lower proportion of patients in the vaccinated group needed oxygen therapy might be due to the effect of vaccination. Among unvaccinated and fully vaccinated patients without initial oxygen demand, the proportions of patients with severe progression were 20.3% (31/153) and 10.8% (13/120), respectively. One study conducted in Korea during the early COVID-19 pandemic showed that 11.7% (16/136) of unvaccinated patients experienced clinical aggravation with a need for oxygen treatment during the clinical course of the disease.

11 As the delta variant was the predominant strain at the time of our study (September–October 2021),

1213 the higher rate of progression observed in our study might be partially due to the virulence of the delta variant. Compared to the fully vaccinated patients, the proportion of unvaccinated patients who experienced severe progression was higher. Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 vaccination significantly prevents severe outcomes and reduces the length of hospitalization in high-risk groups.

1415 The results of our study suggest that a considerable proportion of younger COVID-19 patients with few comorbidities experience high degree of clinical severity and have a need for oxygen therapy in real practice. Fortunately, the oxygen therapy rarely requires invasive ventilation. However, in resource limited settings, even the failure of simple oxygen therapy may lead to a fatal outcome.

Treatment with remdesivir or dexamethasone was associated with severe cases of the disease. Interestingly, the use of antibacterial agents was also higher in the unvaccinated group, despite the assumption that the older group with multiple comorbidities might require more antibiotics to cope with complications of the disease. This somewhat unexpected result might be due to the higher clinical severity of the unvaccinated group and may indirectly reflect the tendency to inappropriately prescribe antibiotics for patients with COVID-19 who show severe symptoms, such as high fever, dyspnea, chest X-ray abnormalities and hypoxemia, not exactly based on the bacterial complications.

1617

Regarding the laboratory findings, an elevated level of LDH at presentation was a predictor of severe progression. One previous study showed that elevated LDH levels during 6–10 days after the onset of illness were associated with clinical aggravation.

11 Abnormal baseline chest X-ray finding was also reported to be a risk factor for oxygen requirement.

18 In this study, chest X-ray abnormalities at the initial presentation were a risk factor for severe progression among unvaccinated and vaccinated patients, and also in fully vaccinated patients. Therefore, several important predictors of severe progression that were identified in unvaccinated patients during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic still appear to be risk factors for severe progression, even under the influence of vaccination and change of dominant variant strain.

Although a previous study reported the occurrence of breakthrough infections in fully vaccinated patients,

19 the clinical characteristics and outcomes of vaccine breakthrough infections have not been systematically compared with those of infections in unvaccinated patients. Breakthrough COVID-19 infection in vaccinated people is also important from both the clinical and the pathophysiological perspectives. As expected based on studies that showed vaccine efficacy in preventing severe COVID-19,

23 vaccination was the only protective factor for severe progression among patients with breakthrough infection and unvaccinated patients. As this study was conducted among hospitalized patients, the results may help clinicians manage patients with the potential of severe progression in hospital settings. As the chest X-ray abnormality was the only risk factor for clinical progression among fully vaccinated patients, it would be necessary to check the chest X-rays early during the patient’s hospitalization and monitor clinical progression more carefully for the patients with initial chest X-ray abnormalities.

This study has several limitations. First, because it was conducted retrospectively at a single center, the generalization of the results may be limited. Second, the number of fully vaccinated patients with severe progression was relatively small. Third, we did not perform virologic analysis of concurrent SARS-CoV-2 variants. However, the likelihood of bias due to the variants may be minimal because most of the study patients were believed to be infected with the delta variant, considering the fact that the dominant viral population in Korea during the study period was the delta variant. Although our results may not be precisely applicable to other variants, the clinical framework could be extrapolated similarly.

In conclusion, we described the clinical features of unvaccinated and vaccinated COVID-19 patients in a hospitalized setting. The only protective factor for severe progression was the vaccination at least once. Among fully vaccinated patients, the chest X-ray abnormality was a predictor for severe progression. In a COVID-19 practice of hospitalized setting, vaccination should be an initial checkpoint for triage and chest X-ray may be helpful in predicting progression.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download