RESULTS

The meaning units reported by participants were organized under seven headings: observed attitude and impression of participants, difficulties due to mental health problems, difficulties due to physical pain, difficulties in relationships, negative changes following the incident, positive changes following the incident, and help needed. Under all headings, 27 themes, 60 sub-themes, and 80 meaning units were elicited.

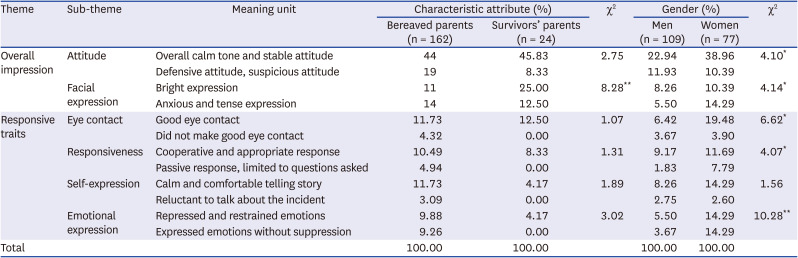

Observed attitude and impression of participants

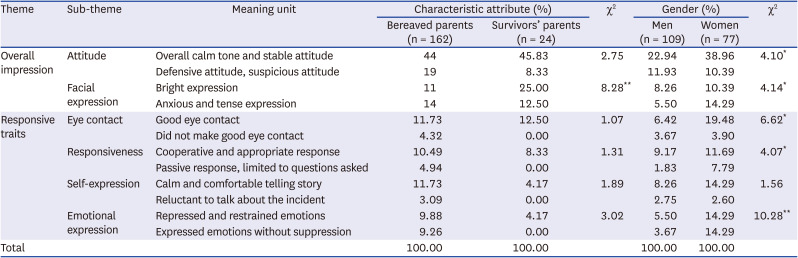

In ‘observed attitude and impression of participants,’ two themes, six sub-themes, and 12 meaning units were elicited. Themes were “overall impression” and “responsive traits,” and sub-themes were “attitude,” “facial expression,” “eye contact,” “responsiveness,” “self-expression,” and “emotional expression.”

More than a quarter (29.57%, n = 55) of participants were calm and stable during the interview, while 11.29% (n = 21) exhibited defensive or suspicious attitudes. Female participants (38.96%, n = 30) were more likely than males (22.94%, n = 25) to exhibit a stable attitude, with a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 4.095, P < 0.05). Parents of survivors (25.00%, n = 6) were more likely than bereaved parents (6.79%, n = 11) to have a bright facial expression and less likely to have tense or anxious facial expressions (12.50%, n = 3). There were statistically significant differences in facial expressions across both characteristic attributes (χ2 = 8.284, P < 0.01) and gender (χ2 =4.135, P < 0.05).

Good eye contact was made by 11.73% (n = 19) of bereaved parents and 12.50% (n = 3) of survivors’ parents, with female respondents (19.48%, n = 15) making better eye contact than males (6.42%, n = 7). Cooperative and appropriate responsiveness was shown by 10.49% (n = 17) of bereaved parents and8.33% (n = 2) of survivors’ parents. Passive responses to questions asked were observed only in bereaved parents (4.94%, n = 8). There was a statistically significant difference in responsiveness across genders (χ2 = 4.074, P < 0.05), but not across characteristic attributes (χ2 = 1.308, P > 0.05).

With regards to descriptions of the event, 11.73% of bereaved parents were calm and comfortable telling their stories; reluctance to talk about the incident was observed in3.09% of bereaved parents. Female respondents (14.29%, n = 11) tended to be more comfortable recounting their stories than males (8.26%, n = 9). More bereaved parents (9.88%, n = 16) than survivors’ parents (4.17%, n = 1) exhibited a tendency to repress and restrain emotion; 9.26% (n = 15) of bereaved parents freely expressed their emotions. There was a statistically significant difference in emotional expression by gender only (χ

2 = 10.284,

P < 0.01) (

Table 1).

Table 1

Observed attitude and impression of participants (N = 186) (multiple responses)

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Meaning unit |

Characteristic attribute (%) |

χ2

|

Gender (%) |

χ2

|

|

Bereaved parents (n = 162) |

Survivors’ parents (n = 24) |

Men (n = 109) |

Women (n = 77) |

|

Overall impression |

Attitude |

Overall calm tone and stable attitude |

44 |

45.83 |

2.75 |

22.94 |

38.96 |

4.10*

|

|

Defensive attitude, suspicious attitude |

19 |

8.33 |

11.93 |

10.39 |

|

Facial expression |

Bright expression |

11 |

25.00 |

8.28**

|

8.26 |

10.39 |

4.14*

|

|

Anxious and tense expression |

14 |

12.50 |

5.50 |

14.29 |

|

Responsive traits |

Eye contact |

Good eye contact |

11.73 |

12.50 |

1.07 |

6.42 |

19.48 |

6.62*

|

|

Did not make good eye contact |

4.32 |

0.00 |

3.67 |

3.90 |

|

Responsiveness |

Cooperative and appropriate response |

10.49 |

8.33 |

1.31 |

9.17 |

11.69 |

4.07*

|

|

Passive response, limited to questions asked |

4.94 |

0.00 |

1.83 |

7.79 |

|

Self-expression |

Calm and comfortable telling story |

11.73 |

4.17 |

1.89 |

8.26 |

14.29 |

1.56 |

|

Reluctant to talk about the incident |

3.09 |

0.00 |

2.75 |

2.60 |

|

Emotional expression |

Repressed and restrained emotions |

9.88 |

4.17 |

3.02 |

5.50 |

14.29 |

10.28**

|

|

Expressed emotions without suppression |

9.26 |

0.00 |

3.67 |

14.29 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

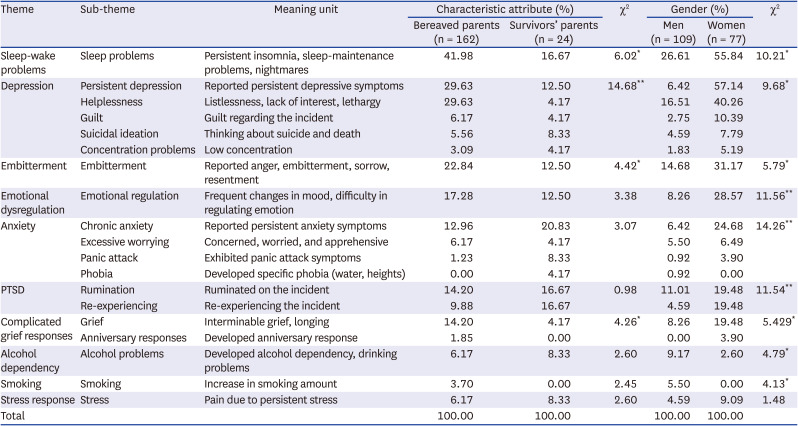

Difficulties due to mental health problems

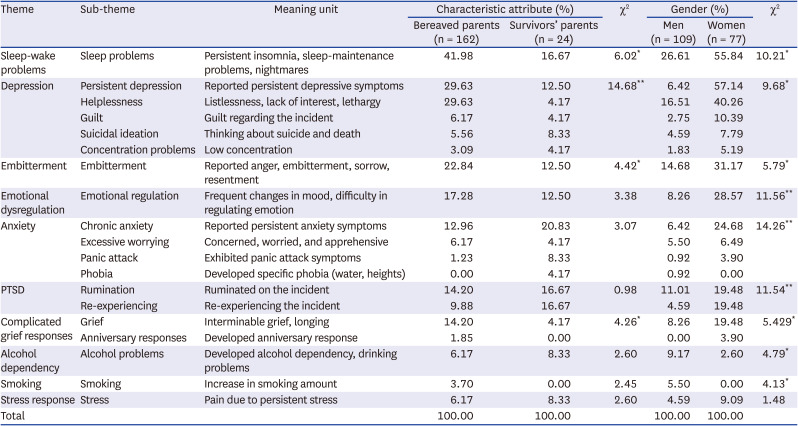

In ‘difficulties due to mental health problems,’ 10 themes, 19 sub-themes, and 19 meaning units were elicited. Themes were ‘sleep-wake problems,’ ‘depression,’ ‘embitterment,’ ‘emotional dysregulation,’ ‘anxiety,’ ‘PTSD,’ ‘complicated grief responses,’ ‘alcohol dependence,’ ‘smoking,’ and ‘stress responses.’

Participants reported experiencing sleep problems including persistent insomnia, difficulty maintaining sleep, and nightmares even five years after the accident. Notably, 41.98% (n = 68) of bereaved parents reported sleep problems, as did 16.67% (n = 4) of survivors’ parents; the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (χ2 = 5.022, P < 0.01). Female respondents (55.84%, n = 43) were more likely than males (26.61%, n = 29) to report sleep problems, with a statistically significant difference between genders (χ2 = 10.207, P < 0.01).

Persistent depressive symptoms were present in 27.42% (n = 51) of total participants, with 26.34% (n = 49) reporting listlessness and lack of energy. In particular, the bereaved parents (29.63%, n = 48) were more likely than parents of survivors (12.50%, n = 3) to report persistent depression; female respondents (57.14%, n = 44) exhibited a higher incidence of depression than males (6.42%, n = 7). Among bereaved parents, 29.63% (n = 48) reported feelings of helplessness, 6.17% (n = 10) reported guilt, and 5.56% (n = 9) reported having suicidal ideations. There was a statistically significant difference in depressive symptoms by characteristic attributes (χ2 = 10.207, P < 0.001). Among female respondents, 40.26% (n = 31) reported feelings of helplessness, 10.39% (n = 8) reported guilt, and 7.79% (n = 6) attested to suicidal ideations. There was a statistically significant difference in depressive symptoms according to gender (χ2 = 10.207, P < 0.01).

Symptoms of embitterment, such as sorrow and resentment, were more often reported by bereaved parents (22.84%, n = 37) than parents of survivors (12.50%, n = 3), and more often by female respondents (31.17%, n = 24) than males (14.68%, n = 16). There were statistically significant differences in embitterment both by gender (χ2 = 5.792, P < 0.01) and characteristic attribute (χ2 = 4.423, P < 0.01). Symptoms of emotional dysregulation, such as frequent changes in mood, were reported by 17.28% (n = 28) of bereaved parents, 12.50% (n = 3) of survivors’ parents, 28.57% (n = 22) of female respondents, and 8.26% (n = 9) of male respondents. There was a statistically significant difference in emotional dysregulation by gender (χ2 = 11.560, P < 0.001).

Chronic anxiety symptoms were more often exhibited by survivors’ parents (20.83%, n = 5) than bereaved parents (12.96%, n = 21), and more often by female respondents (24.68%, n = 19) than males (6.42%, n = 7). In particular, 6.17% (n = 10) of bereaved parents reported excessive worrying, concern, and apprehension; two respondents among bereaved parents and two among survivors’ parents reported panic attacks. One parent whose child survived the accident (4.17%) developed new specific phobia of heights and water. There was a statistically significant difference in anxiety symptoms by gender (χ2 = 14.264, P < 0.001), but not by characteristic attribute (χ2 = 3.069, P > 0.05).

Regarding PTSD symptoms, 14.20% (n = 23) of bereaved parents and 16.67% (n = 4) of survivors’ parents reported rumination, while 9.88% (n = 16) of bereaved parents and 16.67% (n = 4) of survivors’ parents reported re-experiencing the incident. Rumination was more prevalent in female respondents (19.49%, n = 15) than male respondents (11.01%, n = 12), with the same pattern of re-experiencing the event. There was a statistically significant difference in PTSD symptoms by gender only (χ2 = 11.539, P < 0.001). With regards to CG responses, more bereaved parents (14.20%, n = 23) than survivors’ parents (4.17%, n = 1), and more female respondents (19.48%, n = 15) than male respondents (8.26%, n = 9) expressed interminable grief and longing. Notably, three bereaved parents (1.85%) had developed responses to the anniversary of death. There were statistically significant differences in CG responses across both characteristic attribute (χ2 = 4.257, P < 0.05) and gender (χ2 = 5.428, P < 0.05).

In terms of alcohol dependency, male respondents (9.17%, n = 10) were more likely than female respondents (2.60%, n = 2) to report alcohol-related problems, with a statistically significant difference by gender (χ

2 =4.794,

P < 0.05). Six bereaved parents (3.70%), all of whom were male, experienced difficulties due to increased smoking, with a statistically significant difference by gender only (χ

2 = 4.125,

P < 0.05). In terms of stress responses, 6.17% of bereaved parents, 8.33% of survivors’ parents, 9.09% of females, and 4.59% of males were afflicted with chronic stress (

Table 2).

Table 2

Difficulties due to mental health problems (N = 186) (multiple responses)

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Meaning unit |

Characteristic attribute (%) |

χ2

|

Gender (%) |

χ2

|

|

Bereaved parents (n = 162) |

Survivors’ parents (n = 24) |

Men (n = 109) |

Women (n = 77) |

|

Sleep-wake problems |

Sleep problems |

Persistent insomnia, sleep-maintenance problems, nightmares |

41.98 |

16.67 |

6.02*

|

26.61 |

55.84 |

10.21*

|

|

Depression |

Persistent depression |

Reported persistent depressive symptoms |

29.63 |

12.50 |

14.68**

|

6.42 |

57.14 |

9.68*

|

|

Helplessness |

Listlessness, lack of interest, lethargy |

29.63 |

4.17 |

16.51 |

40.26 |

|

Guilt |

Guilt regarding the incident |

6.17 |

4.17 |

2.75 |

10.39 |

|

Suicidal ideation |

Thinking about suicide and death |

5.56 |

8.33 |

4.59 |

7.79 |

|

Concentration problems |

Low concentration |

3.09 |

4.17 |

1.83 |

5.19 |

|

Embitterment |

Embitterment |

Reported anger, embitterment, sorrow, resentment |

22.84 |

12.50 |

4.42*

|

14.68 |

31.17 |

5.79*

|

|

Emotional dysregulation |

Emotional regulation |

Frequent changes in mood, difficulty in regulating emotion |

17.28 |

12.50 |

3.38 |

8.26 |

28.57 |

11.56**

|

|

Anxiety |

Chronic anxiety |

Reported persistent anxiety symptoms |

12.96 |

20.83 |

3.07 |

6.42 |

24.68 |

14.26**

|

|

Excessive worrying |

Concerned, worried, and apprehensive |

6.17 |

4.17 |

5.50 |

6.49 |

|

Panic attack |

Exhibited panic attack symptoms |

1.23 |

8.33 |

0.92 |

3.90 |

|

Phobia |

Developed specific phobia (water, heights) |

0.00 |

4.17 |

0.92 |

0.00 |

|

PTSD |

Rumination |

Ruminated on the incident |

14.20 |

16.67 |

0.98 |

11.01 |

19.48 |

11.54**

|

|

Re-experiencing |

Re-experiencing the incident |

9.88 |

16.67 |

4.59 |

19.48 |

|

Complicated grief responses |

Grief |

Interminable grief, longing |

14.20 |

4.17 |

4.26*

|

8.26 |

19.48 |

5.429*

|

|

Anniversary responses |

Developed anniversary response |

1.85 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

3.90 |

|

Alcohol dependency |

Alcohol problems |

Developed alcohol dependency, drinking problems |

6.17 |

8.33 |

2.60 |

9.17 |

2.60 |

4.79*

|

|

Smoking |

Smoking |

Increase in smoking amount |

3.70 |

0.00 |

2.45 |

5.50 |

0.00 |

4.13*

|

|

Stress response |

Stress |

Pain due to persistent stress |

6.17 |

8.33 |

2.60 |

4.59 |

9.09 |

1.48 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

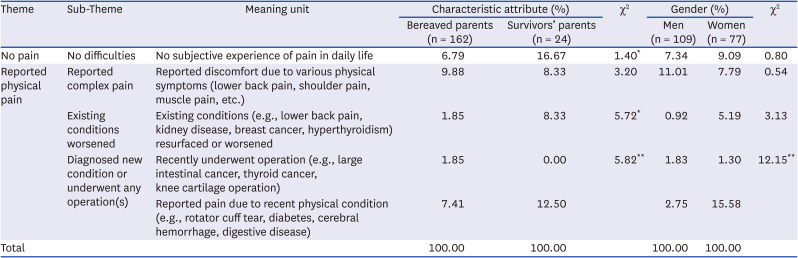

Difficulties due to physical pain

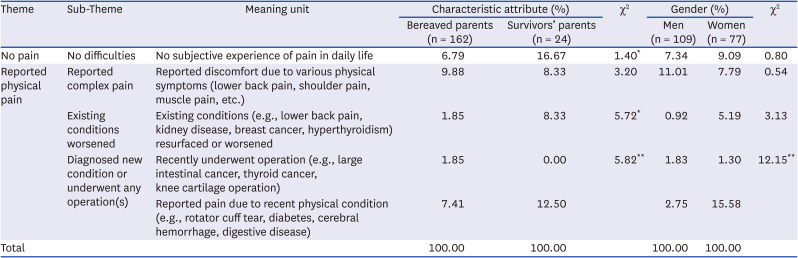

For the classification of ‘difficulties due to physical pain,’ two themes, four sub-themes, and five meaning units were elicited. Themes were ‘no pain’ and ‘reported physical pain’; sub-themes were ‘no difficulties,’ ‘reported complex pain,’ ‘existing conditions worsened,’ and ‘diagnosed new conditions or underwent any operation(s).’

Survivors’ parents (16.67%, n = 4), compared to bereaved parents (6.79%, n = 11), were more likely to report no subjective experience of pain during their day-to-day lives, with a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 1.401, P < 0.05) by characteristic attribute.

Roughly 105 (9.88%, n = 16) of bereaved parents and 8.33% (n = 2) of survivors’ parents suffered from a variety of physical symptoms, with more male respondents (11.01%, n = 12) than female respondents (7.79%, n = 6) reporting complex pain. Respondents often referred to lower back pain, shoulder pain, and muscle pain. Also, three bereaved parents (1.85%) and two (8.33%) survivors’ parents reported worsening of existing conditions or resurfacing of past conditions such as lower back pain, kidney disease, breast cancer, or hyperthyroidism. There was a statistically significant difference in worsening existing conditions by characteristic attribute (χ2 = 5.716, P < 0.05), but not by gender (χ2 = 3.132, P > 0.05).

Three bereaved parents (1.85%) reported having recently undergone an operation. In addition, 7.41% (n = 12) of bereaved parents and 12.50% (n = 3) of survivors’ parents experienced pain from recent physical ailments, with more female respondents (15.58%, n = 12) than male respondents (2.75%, n = 3) reporting the experience of recent physical pain. There were statistically significant differences in this subtheme by both characteristic attribute (χ

2 = 5.824,

P < 0.01) and gender (χ

2 = 12.150,

P < 0.01) (

Table 3).

Table 3

Difficulties due to physical pain (N = 186) (multiple responses)

|

Theme |

Sub-Theme |

Meaning unit |

Characteristic attribute (%) |

χ2

|

Gender (%) |

χ2

|

|

Bereaved parents (n = 162) |

Survivors’ parents (n = 24) |

Men (n = 109) |

Women (n = 77) |

|

No pain |

No difficulties |

No subjective experience of pain in daily life |

6.79 |

16.67 |

1.40*

|

7.34 |

9.09 |

0.80 |

|

Reported physical pain |

Reported complex pain |

Reported discomfort due to various physical symptoms (lower back pain, shoulder pain, muscle pain, etc.) |

9.88 |

8.33 |

3.20 |

11.01 |

7.79 |

0.54 |

|

Existing conditions worsened |

Existing conditions (e.g., lower back pain, kidney disease, breast cancer, hyperthyroidism) resurfaced or worsened |

1.85 |

8.33 |

5.72*

|

0.92 |

5.19 |

3.13 |

|

Diagnosed new condition or underwent any operation(s) |

Recently underwent operation (e.g., large intestinal cancer, thyroid cancer, knee cartilage operation) |

1.85 |

0.00 |

5.82**

|

1.83 |

1.30 |

12.15**

|

|

Reported pain due to recent physical condition (e.g., rotator cuff tear, diabetes, cerebral hemorrhage, digestive disease) |

7.41 |

12.50 |

2.75 |

15.58 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

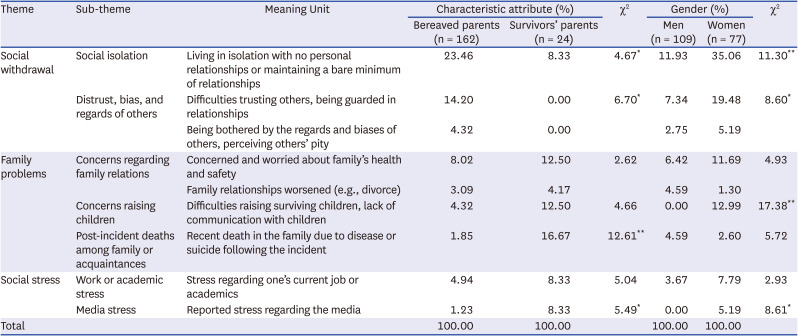

Difficulties in relationships

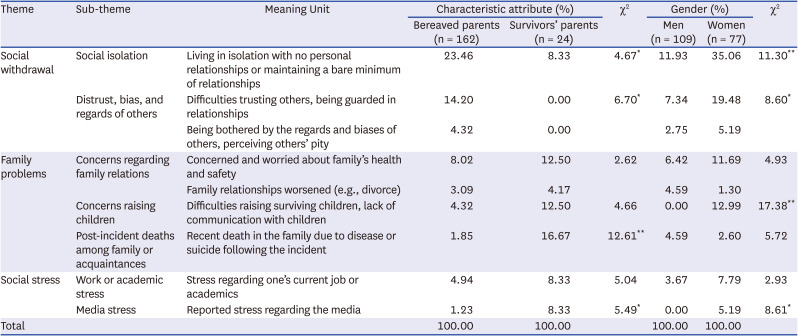

Under the ‘difficulties in relationships’ classification, three themes, seven sub-themes, and nine meaning units were elicited. Themes were ‘social withdrawal,’ ‘family problems,’ and ‘social stress.’ Sub-themes were ‘social isolation,’ ‘distrust, bias, and regards of others,’ ‘concerns regarding family relations,’ ‘concerns raising children,’ ‘post-incident deaths among family or acquaintances,’ ‘work or academic stress,’ and ‘media stress.’

About one third (37.63%, n = 70) of all respondents attested to social withdrawal. In particular, the bereaved parents (23.46%, n = 38) were more likely than survivors’ parents (8.33%, n = 2) to refer to relationships being severed. Female respondents (35.06%, n = 27) were more likely than male respondents (11.93%, n = 13) to report social isolation or maintaining a bare minimum of social relationships. There were statistically significant differences in social withdrawal both by characteristic attribute (χ2 = 4.672, P < 0.05) and gender (χ2 = 11.295, P < 0.01). Notably, 14.20% (n = 23) of bereaved parents reported having trouble trusting others and being guarded in their approach to relationships. Also, seven bereaved parents (4.32%) reported being conscious of others’ regards and/or bias towards themselves, and perceived those others were regarding them with pity. Female respondents (19.48%, n = 15), more than males (7.34%, n = 8), reported feeling guarded in their relationships. The differences in this category of distrust toward others were statistically significant across both characteristic attributes (χ2 = 6.697, P < 0.05) and gender (χ2 = 8.601, P < 0.05).

In addition, 12.50% (n = 3) of survivors’ parents and8.02% (n = 13) of bereaved parents were concerned about their families’ health and safety; five bereaved parents (3.09%) and one survivor’s parent (4.17%) reported that their relationships with their own parents had worsened. Survivors’ parents (12.50%, n = 3) were more likely than bereaved parents (4.32%, n = 7) to encounter difficulties in raising their surviving children and struggle from a lack of communication with their children. In particular, 12.99% (n = 10) of female respondents had concerns about raising children. There was a statistically significant difference only by gender (χ2 = 17.380, P < 0.001) for this sub-theme.

Three bereaved parents (1.85%) and four survivors’ parents (16.67%) struggled from recent (post-accident) deaths in the family caused by disease or suicide, with a statistically significant difference across characteristic attributes (χ

2 = 12.614,

P < 0.001). Meanwhile, 10 respondents (5.38%) experienced stress in their current job or academic situation, and four respondents (2.15%) reported stress from media reports regarding the incident. There were statistically significant differences in media-related stress across both characteristic attributes (χ

2 = 5.491,

P < 0.05) and gender (χ

2 = 8.614,

P < 0.05) (

Table 4).

Table 4

Difficulties in relationships (N = 186) (multiple responses)

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Meaning Unit |

Characteristic attribute (%) |

χ2

|

Gender (%) |

χ2

|

|

Bereaved parents (n = 162) |

Survivors’ parents (n = 24) |

Men (n = 109) |

Women (n = 77) |

|

Social withdrawal |

Social isolation |

Living in isolation with no personal relationships or maintaining a bare minimum of relationships |

23.46 |

8.33 |

4.67*

|

11.93 |

35.06 |

11.30**

|

|

Distrust, bias, and regards of others |

Difficulties trusting others, being guarded in relationships |

14.20 |

0.00 |

6.70*

|

7.34 |

19.48 |

8.60*

|

|

Being bothered by the regards and biases of others, perceiving others’ pity |

4.32 |

0.00 |

2.75 |

5.19 |

|

Family problems |

Concerns regarding family relations |

Concerned and worried about family’s health and safety |

8.02 |

12.50 |

2.62 |

6.42 |

11.69 |

4.93 |

|

Family relationships worsened (e.g., divorce) |

3.09 |

4.17 |

4.59 |

1.30 |

|

Concerns raising children |

Difficulties raising surviving children, lack of communication with children |

4.32 |

12.50 |

4.66 |

0.00 |

12.99 |

17.38**

|

|

Post-incident deaths among family or acquaintances |

Recent death in the family due to disease or suicide following the incident |

1.85 |

16.67 |

12.61**

|

4.59 |

2.60 |

5.72 |

|

Social stress |

Work or academic stress |

Stress regarding one’s current job or academics |

4.94 |

8.33 |

5.04 |

3.67 |

7.79 |

2.93 |

|

Media stress |

Reported stress regarding the media |

1.23 |

8.33 |

5.49*

|

0.00 |

5.19 |

8.61*

|

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

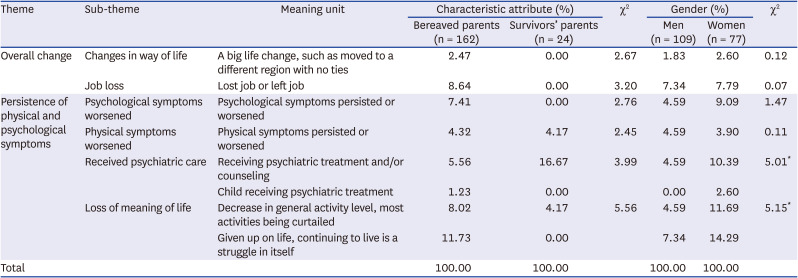

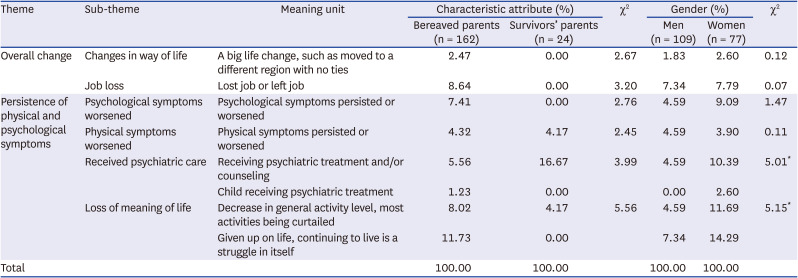

Negative changes following the incident

For the ‘negative changes following the incident’ classification, two themes, six sub-themes, and eight meaning units were elicited. Themes were ‘overall change,’ and ‘persistence of physical and psychological symptoms’; sub-themes were ‘changes in the way of life,’ ‘job loss,’ ‘psychological symptoms worsened,’ ‘physical symptoms worsened,’ ‘received psychiatric care,’ and ‘loss of meaning of life.’

Four bereaved parents (2.47%) reported a big life change in their lives and had moved to a different region in which they had no ties. Fourteen bereaved respondents (8.64%) reported having lost or left their jobs. A general persistence of physical and/or psychological symptoms was noted.7.41% (n = 12) of bereaved parents reported that their psychological symptoms had worsened, among whom seven (9.09%) were female and five (4.59%) were male. Seven bereaved parents (4.32%) reported persistence or worsening of physical symptoms. 16.67% (n = 4) of survivors’ parents and 5.56% (n = 9) of bereaved parents were receiving psychiatric treatment and consultation at the time this study was conducted; two bereaved parents (1.23%) stated that their children were receiving psychiatric treatment. There were statistically significant differences in psychiatric treatment across both characteristic attributes (χ2 = 3.989, P < 0.05) and gender (χ2 = 5.005, P < 0.05).

Meanwhile, 8.02% (n = 3) of bereaved parents and 4.17% (n = 1) of survivors’ parents noted a decrease in activity levels such that most aspects of life had been curtailed. Female respondents (11.69%, n = 9) were more likely than males (4.59%, n = 5) to state that their life had lost its meaning. Notably, 19 bereaved respondents (11.73%) attested to having given up on life and found that continuing to live was a struggle in itself. There were statistically significant differences in loss of meaning of life by both characteristic attribute (χ

2 = 5.559,

P < 0.05) and gender (χ

2 = 5.154,

P < 0.05) (

Table 5).

Table 5

Negative changes following the incident (N = 186) (multiple responses)

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Meaning unit |

Characteristic attribute (%) |

χ2

|

Gender (%) |

χ2

|

|

Bereaved parents (n = 162) |

Survivors’ parents (n = 24) |

Men (n = 109) |

Women (n = 77) |

|

Overall change |

Changes in way of life |

A big life change, such as moved to a different region with no ties |

2.47 |

0.00 |

2.67 |

1.83 |

2.60 |

0.12 |

|

Job loss |

Lost job or left job |

8.64 |

0.00 |

3.20 |

7.34 |

7.79 |

0.07 |

|

Persistence of physical and psychological symptoms |

Psychological symptoms worsened |

Psychological symptoms persisted or worsened |

7.41 |

0.00 |

2.76 |

4.59 |

9.09 |

1.47 |

|

Physical symptoms worsened |

Physical symptoms persisted or worsened |

4.32 |

4.17 |

2.45 |

4.59 |

3.90 |

0.11 |

|

Received psychiatric care |

Receiving psychiatric treatment and/or counseling |

5.56 |

16.67 |

3.99 |

4.59 |

10.39 |

5.01*

|

|

Child receiving psychiatric treatment |

1.23 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

2.60 |

|

Loss of meaning of life |

Decrease in general activity level, most activities being curtailed |

8.02 |

4.17 |

5.56 |

4.59 |

11.69 |

5.15*

|

|

Given up on life, continuing to live is a struggle in itself |

11.73 |

0.00 |

7.34 |

14.29 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

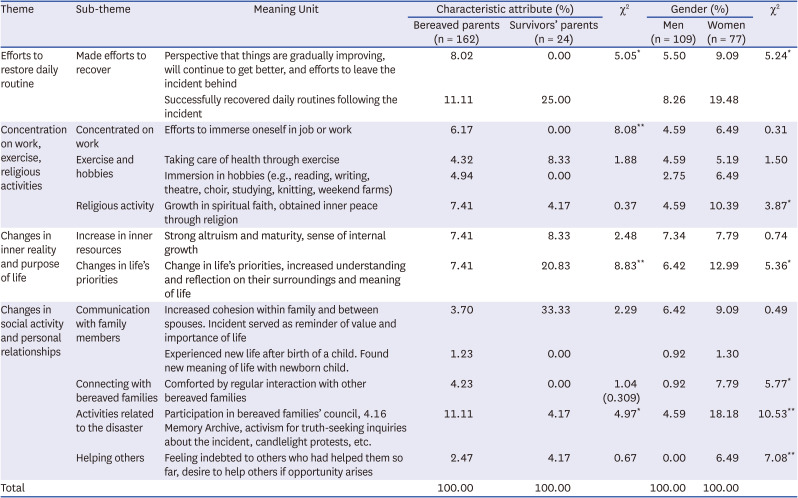

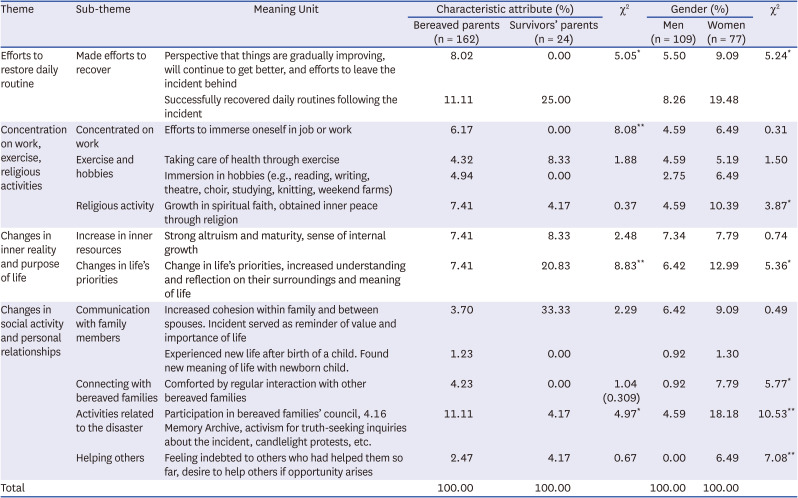

Positive changes following the incident

For the classification of ‘positive changes following the incident,’ four themes, 10 sub-themes, and 13 meaning units were elicited. Themes were ‘efforts to restore daily routine,’ ‘concentration on work, exercise, religious activities,’ ‘changes in inner reality and purpose of life,’ and ‘changes in social activity and personal relationships.’ Sub-themes were ‘made efforts to recover,’ ‘concentrated on work,’ ‘exercise and hobbies,’ ‘religious activity,’ ‘increase in inner resources,’ ‘changes in life’s priorities,’ ‘communication with family members,’ ‘connecting with bereaved families,’ ‘activities related to the disaster,’ and ‘helping others.’

Thirty-seven participants (19.89%) reported making efforts to recover their daily routines. Among respondents from bereaved families, 13 parents (8.02%) felt that their lives were gradually improving and would continue to improve and showed efforts to leave the accident behind. More parents of survivors (25.00%, n = 6) than those of children who had died (11.11%, n = 18), and more female respondents (19.48%, n = 15) than male respondents (8.26%, n = 9) reported having recovered their daily routines after the incident, with statistically significant differences according to characteristic attributes (χ2 = 5.051, P < 0.05) and gender (χ2 = 5.236, P < 0.05).

Efforts to concentrate on work, exercise, and religious activities were observed. Notably, while 6.17% (n = 10) of bereaved parents reported efforts to immerse themselves in their work, no such efforts were mentioned by survivors’ parents. There was a statistically significant difference in immersion in work only according to characteristic attributes (χ2 = 8.083, P < 0.01). Furthermore, 4.32% (n = 7) of bereaved parents and 8.33% (n = 2) of survivors’ parents managed their health through exercise. Immersion in hobbies was noted by eight respondents (4.94%) among bereaved parents, with hobbies including reading, writing, theater, choir, studying, knitting, and visiting farms on weekends. Growth in spiritual faith was reported by more bereaved parents (7.41%, n = 12) than survivors’ parents (4.17%, n = 1), and more female respondents (10.39%, n = 8) than males (4.59%, n = 5). These respondents reported having gained inner peace through religion. There was a statistically significant difference in religious activity by gender (χ2 = 3.865, P < 0.05).

Participants also mentioned seeing a positive change in their inner resources and meaning of life. The 7.41% (n = 12) of bereaved parents and 8.33% (n = 2) of survivors’ parents reported an increase in altruism and maturity with a sense of internal growth. Changes in life’s priorities were noted by 20.83% (n = 5) of survivor’s parents compared to 7.41% of bereaved parents (n = 12), and in more female respondents (12.99%, n = 10) than male respondents (6.42%, n = 7). These respondents reported an increased understanding of their surroundings and reflection on the meaning of life. There were statistically significant differences in changes in life’s priorities both across characteristic attributes (χ2 = 8.833, P < 0.01) and gender (χ2 = 5.361, P < 0.05).

Some parents also noted a positive change in social activities and relationships. Roughly one third 33.33% (n = 8) of survivors’ parents compared to 3.70% (n = 6) of bereaved parents reported increased cohesion within the family after the disaster, noting that the accident served as a reminder of the value and importance of family. Meanwhile, two bereaved parents (1.23%) experienced life anew upon having a new child after the accident and reported new meaning in their life due to raising their newborn. 4.23% (n = 7) of bereaved parents reported receiving significant comfort through regularly interacting with members of other bereaved families; most of these respondents were female (7.79%, n = 6).

Additionally, 11.11% (n = 18) of bereaved parents participated in disaster-related activism such as the bereaved families’ council, the 4.16 Memory Archive, demands for investigation into the reasons for the accident, and candlelight protests, among other protest activities. Female respondents (18.18%, n = 14) were more engaged in these initiatives than male respondents (4.59%, n = 5). There were statistically significant differences in disaster-related activities across both characteristic attributes (χ

2 = 4.968,

P < 0.05) and gender (χ

2 = 10.526,

P < 0.01). Furthermore, 2.47% (n = 4) of bereaved parents and 4.17% (n = 1) of survivors’ parents reported feeling indebted to others who had helped them so far and expressed the desire for an opportunity to help others in the future. There was a statistically significant difference in the desire to help others based on gender (χ

2 = 7.078,

P < 0.01) (

Table 6).

Table 6

Positive changes following the incident (N = 186) (multiple responses)

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Meaning Unit |

Characteristic attribute (%) |

χ2

|

Gender (%) |

χ2

|

|

Bereaved parents (n = 162) |

Survivors’ parents (n = 24) |

Men (n = 109) |

Women (n = 77) |

|

Efforts to restore daily routine |

Made efforts to recover |

Perspective that things are gradually improving, will continue to get better, and efforts to leave the incident behind |

8.02 |

0.00 |

5.05*

|

5.50 |

9.09 |

5.24*

|

|

Successfully recovered daily routines following the incident |

11.11 |

25.00 |

8.26 |

19.48 |

|

Concentration on work, exercise, religious activities |

Concentrated on work |

Efforts to immerse oneself in job or work |

6.17 |

0.00 |

8.08**

|

4.59 |

6.49 |

0.31 |

|

Exercise and hobbies |

Taking care of health through exercise |

4.32 |

8.33 |

1.88 |

4.59 |

5.19 |

1.50 |

|

Immersion in hobbies (e.g., reading, writing, theatre, choir, studying, knitting, weekend farms) |

4.94 |

0.00 |

2.75 |

6.49 |

|

Religious activity |

Growth in spiritual faith, obtained inner peace through religion |

7.41 |

4.17 |

0.37 |

4.59 |

10.39 |

3.87*

|

|

Changes in inner reality and purpose of life |

Increase in inner resources |

Strong altruism and maturity, sense of internal growth |

7.41 |

8.33 |

2.48 |

7.34 |

7.79 |

0.74 |

|

Changes in life’s priorities |

Change in life’s priorities, increased understanding and reflection on their surroundings and meaning of life |

7.41 |

20.83 |

8.83**

|

6.42 |

12.99 |

5.36*

|

|

Changes in social activity and personal relationships |

Communication with family members |

Increased cohesion within family and between spouses. Incident served as reminder of value and importance of life |

3.70 |

33.33 |

2.29 |

6.42 |

9.09 |

0.49 |

|

Experienced new life after birth of a child. Found new meaning of life with newborn child. |

1.23 |

0.00 |

0.92 |

1.30 |

|

Connecting with bereaved families |

Comforted by regular interaction with other bereaved families |

4.23 |

0.00 |

1.04 (0.309) |

0.92 |

7.79 |

5.77*

|

|

Activities related to the disaster |

Participation in bereaved families’ council, 4.16 Memory Archive, activism for truth-seeking inquiries about the incident, candlelight protests, etc. |

11.11 |

4.17 |

4.97*

|

4.59 |

18.18 |

10.53**

|

|

Helping others |

Feeling indebted to others who had helped them so far, desire to help others if opportunity arises |

2.47 |

4.17 |

0.67 |

0.00 |

6.49 |

7.08**

|

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

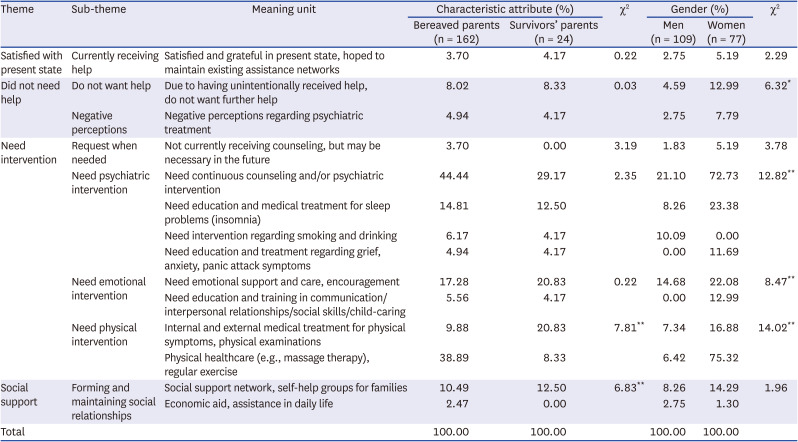

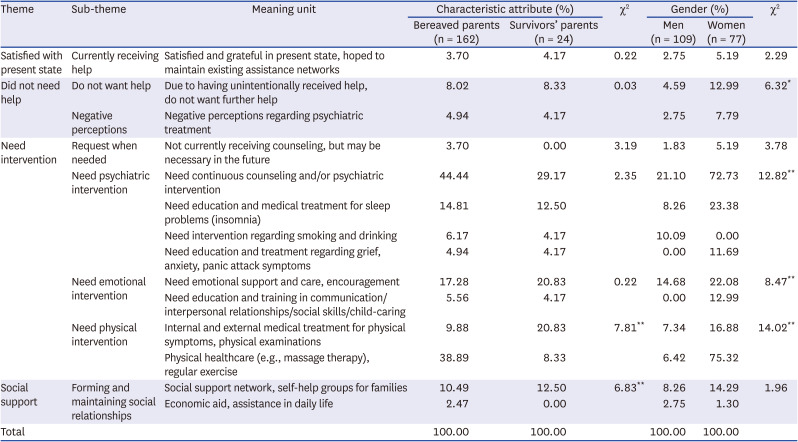

Help needed

In the help needed category, four themes, eight sub-themes, and 14 meaning units were elicited. Themes were ‘satisfied with present state,’ ‘did not need help,’ ‘need intervention,’ and ‘social support.’ Sub-themes were ‘currently receiving help,’ ‘do not want help,’ ‘negative perceptions,’ ‘request when needed,’ ‘need psychiatric intervention,’ ‘need emotional intervention,’ ‘need physical intervention,’ and ‘forming and maintaining social relationships.’

Only 3.70% (n = 6) of bereaved parents and 4.17% (n = 1) of survivor’s parents reported satisfaction and gratitude with regards to their present state and hoped to maintain their existing assistance networks. However, 8.02% (n = 13) of bereaved parents and 8.33% (n = 2) of survivor’s parents did not wish to receive further help due to having received what they considered too much help. 4.94% of bereaved parents and 4.17% of survivor’s parents had negative perceptions of psychiatric treatment, while 7.79% of female respondents had negative perceptions of psychiatric treatment. There was a statistically significant difference in negative perceptions of psychiatric help by gender (χ2 = 6.317, P < 0.05).

Need for psychiatric, emotional, and physical intervention was also apparent. Six bereaved parents (3.70%) stated they were not currently receiving counseling but acknowledged that they might need counseling in the future. Bereaved parents (44.44%, n = 72) were more likely than survivors’ parents (29.17%, n = 7) to report a need for continuous counseling and/or psychiatric intervention, as were female respondents (72.73%, n = 56) compared to male respondents (21.10%, n = 23). The 14.81% (n = 24) of bereaved parents and 12.50% (n = 3) of survivors; parents expressed a desire for education and medical treatment for sleep problems and insomnia. Eleven respondents (5.91%) stated a need for intervention regarding smoking and/or drinking problems, and nine respondents (4.84%) desired education and treatment regarding grief, panic, and anxiety symptoms. There was a statistically significant difference in the expressed need for psychiatric intervention between males and females (χ2 = 12.822, P < 0.001), but not across characteristic attributes (χ2 = 2.346, P > 0.05).

Need for continuous emotional support, care, and encouragement was noted in more parents of survivors of (20.83%, n = 5) than those of deceased children (17.28%, n = 28), and more female respondents (22.08%, n = 17) than male respondents (14.68%, n = 16). Meanwhile, 5.56% of bereaved parents (n = 9) and 4.17% (n = 1) of survivors’ parents reported a desire for education and training in communication skills, interpersonal relationships, social skills, and child-rearing skills. Need for intervention regarding physical symptoms, such as internal medicine or external medical treatments and physical examinations, was expressed by more parents of survivors (20.83%, n = 5) than those whose children had died in the accident (9.88%, n = 16), and more female respondents (16.88%, n = 13) than male respondents (7.34%, n = 8). In particular, 38.89% (n = 63) of bereaved parents noted the necessity of physical healthcare such as massage therapies and regular exercise, most of whom were female (75.32%, n = 58). There were statistically significant differences in the need for physical intervention by both characteristic attributes (χ2 = 7.807, P < 0.01) and gender (χ2 = 14.015, P < 0.001).

Need for social support was also noted. 10.49% (n = 17) of bereaved parents and 12.50% (n = 3) of survivors’ parents reported a need for social support network and activities such as self-help groups. Four individuals (2.47%) from bereaved families reported the need for economic aid and assistance in daily life. There was a statistically significant difference in this theme across characteristic attributes (χ

2 = 6.828,

P < 0.01) (

Table 7).

Table 7

Help needed (N = 186) (multiple responses)

|

Theme |

Sub-theme |

Meaning unit |

Characteristic attribute (%) |

χ2

|

Gender (%) |

χ2

|

|

Bereaved parents (n = 162) |

Survivors’ parents (n = 24) |

Men (n = 109) |

Women (n = 77) |

|

Satisfied with present state |

Currently receiving help |

Satisfied and grateful in present state, hoped to maintain existing assistance networks |

3.70 |

4.17 |

0.22 |

2.75 |

5.19 |

2.29 |

|

Did not need help |

Do not want help |

Due to having unintentionally received help, do not want further help |

8.02 |

8.33 |

0.03 |

4.59 |

12.99 |

6.32*

|

|

Negative perceptions |

Negative perceptions regarding psychiatric treatment |

4.94 |

4.17 |

2.75 |

7.79 |

|

Need intervention |

Request when needed |

Not currently receiving counseling, but may be necessary in the future |

3.70 |

0.00 |

3.19 |

1.83 |

5.19 |

3.78 |

|

Need psychiatric intervention |

Need continuous counseling and/or psychiatric intervention |

44.44 |

29.17 |

2.35 |

21.10 |

72.73 |

12.82**

|

|

Need education and medical treatment for sleep problems (insomnia) |

14.81 |

12.50 |

8.26 |

23.38 |

|

Need intervention regarding smoking and drinking |

6.17 |

4.17 |

10.09 |

0.00 |

|

Need education and treatment regarding grief, anxiety, panic attack symptoms |

4.94 |

4.17 |

0.00 |

11.69 |

|

Need emotional intervention |

Need emotional support and care, encouragement |

17.28 |

20.83 |

0.22 |

14.68 |

22.08 |

8.47**

|

|

Need education and training in communication/interpersonal relationships/social skills/child-caring |

5.56 |

4.17 |

0.00 |

12.99 |

|

Need physical intervention |

Internal and external medical treatment for physical symptoms, physical examinations |

9.88 |

20.83 |

7.81**

|

7.34 |

16.88 |

14.02**

|

|

Physical healthcare (e.g., massage therapy), regular exercise |

38.89 |

8.33 |

6.42 |

75.32 |

|

Social support |

Forming and maintaining social relationships |

Social support network, self-help groups for families |

10.49 |

12.50 |

6.83**

|

8.26 |

14.29 |

1.96 |

|

Economic aid, assistance in daily life |

2.47 |

0.00 |

2.75 |

1.30 |

|

Total |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

DISCUSSION

This study examined the experiences of bereaved parents of victims and parents of survivors of the Sewol Ferry accident after five years. Data from in-depth interviews were categorized under seven headings: observed attitude and impression of participants, difficulties due to mental health symptoms, difficulties due to physical pain, difficulties in relationships, negative changes following the incident, positive changes following the incident, and help needed. Twenty-seven themes, 60 sub-themes, and 80 meaning units were elicited.

Even five years after the Sewol Ferry accident, 38% of respondents reported problems sleeping. Respondents experienced long-term depression, helplessness, guilt, suicidal ideations, and concentration problems; 57% of female respondents reported long-term depression. As for PTSD symptoms, rumination was observed in 14.20% of bereaved parents and 16.67% of survivors’ parents; more than 10% of total respondents reported re-experiencing symptoms. These results are consistent with a prior study of 241 survivors, survivor family members, and bereaved family members of the Sewol Ferry incident that found the correlations among the severity of PTSD, posttraumatic growth (PTG), and posttraumatic embitterment disorder differed according to the level of social support.

8 Another study which examined the psycho-social attributes of 51 bereaved families one year after the loss of a spouse or child

19 found a statistically significant decrease in depression symptoms only, and no significant changes in the level of social functioning or pain. In a different study, stronger and more persistent symptoms of sadness and depression were reported when the bereaved person had lost a child than a parent, sibling, or spouse.

20 In addition, more than 20% of respondents in this study reported embitterment symptoms, including sorrow and resentment. This echoes the findings from a previous study of bereaved families of Sewol Ferry victims, which also noted the presence of embitterment regarding the accident, rejection of unjust realities, fear and anxiety of abandonment, and sorrow.

21 Embitterment can hinder the pursuit of functional solutions to life’s problems, and paralyze emotions.

2223 Since chronic embitterment can cause serious damage and pain to the person and to those around them protective factors to overcome such embitterment need to be investigated.

24

Social withdrawal was reported by 37.63% of respondents. Some completely cut off all personal relationships, while most maintained only the minimum necessary to carry out their lives. Notably, 18.52% of bereaved parents struggled with distrust, wariness, and bias towards other people, with more female respondents reporting fear in relationships than males. Bereaved parents were more likely than survivors’ parents to report concern about their families’ health and safety. Some bereaved parents reported moving to a different region where they had no ties, describing a complete 180-degree change in their lives. While 8.64% of bereaved parents reported losing or leaving their job, the same was not reported by survivors’ parents. These results are consistent with prior studies that found that experiencing traumatic stress results in destructive emotions and damages functional coping, and that psychological pain is correlated with the loss of one’s job.

22 Bereaved parents were also more likely than survivors’ parents to report a general decrease in activity and curtailment of most of life’s aspects. Female respondents were more likely than males to find life itself a burden and to report a loss of meaning and purpose in life, which is another finding that merits attention.

Emotional dysregulation due to frequent changes in emotion was more prevalent in female respondents than male respondents; symptoms of chronic anxiety and excessive worry were reported by bereaved parents. In addition, 14.20% of bereaved parents reported symptoms of interminable grief and longing for their lost children and noted death-anniversary responses. Although grief symptoms generally decrease with the passage of time, it is important in the case of bereaved parents to evaluate the process of grief as well as persistent PTSD symptoms on a long-term basis.

1925 Further research into the various factors that may facilitate change and recovery is needed. It is possible that experiencing a negative life event can lead to psychopathological symptoms. These findings highlight the importance of continued evaluation and intervention in bereaved families. Meanwhile, male respondents exhibited a much greater incidence of alcohol and smoking problems than females. Analysis of data from the World Trade Center (WTC) Health Registry 10 years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks found that socioeconomic status, social resources, and life experiences prior to the incident had a greater effect on psychiatric symptoms than gender.

20 Thus, it is important to consider a wide range of factors when investigating the psychiatric status and struggles of bereaved parents members and survivors’ parents.

In addition, 44% of bereaved parents reported a need for psychiatric, emotional, and physical intervention. Bereaved parents experienced more psychological and physical symptoms than survivors’ parents; they and their families were receiving more psychiatric treatment due to such symptoms. Seventy-three percent of female respondents expressed a need for continuous psychotherapy and psychiatric intervention, and education and training on child education, as well as communication and interpersonal skills. In particular, female respondents reported struggling with how to care for their surviving children and appropriately communicating with their children. A previous study of 54 families of Sewol Ferry victims focusing on changes in social relationships found that intra-family communications generally decreased, but increased in some cases; consistent with this study’s findings, concerns regarding surviving children were noted.

5 In an interpretive phenomenological analysis of 16 bereaved parents of Sewol Ferry victims,

21 respondents discussed changes in child-raising approaches, parent-child conflicts, and educating their surviving children, which indicated a need for assistance and aid with child-rearing. This echoes the present study’s findings; training and in-depth understanding about how to respond to the emotions of surviving children and appropriate child-raising practices are needed. Another study of 48 survivors of the Sewol Ferry incident

22 emphasized the need to strengthen social support after experiencing a traumatic event. Providing social resources to bereaved families can protect mental health.

23 Mental health recovery can be facilitated by establishing social support networks and activities such as self-help groups for bereaved families.

Notwithstanding these difficulties, about 20% of respondents exhibited a positive attitude in pursuing recovery. Survivors’ parents stressed the value and importance of family and noted increased cohesion within the family. Female respondents, more than males, were comforted through regular interaction with other bereaved families. It is notable that bereaved family respondents focused on political activism (to demand truth-seeking investigations regarding the accident) and participated in the bereaved families’ council. Respondents were grateful for the help they received and expressed a desire to help others when the opportunity arose. Bereaved parents, compared to survivors’ parents, exhibited more efforts to immerse themselves in their work, and concentrated more on hobbies and religious activities to pursue inner peace. Experiencing immersion in activities resulted in a change in life’s priorities and inner growth in many participants, which is consistent with prior studies that found that performing alternative activities such as regular exercise and hobbies can help PTSD-diagnosed individuals lower their stress levels and address psychological symptoms.

2425 The findings illustrate that finding one’s meaning of life is an important factor in enhancing recovery following a negative incident.

22 In particular, one study of bereaved families showed that socialization is a critical factor in managing stress and sadness.

26 Therefore, it appears that socialization shifts the focus of traumatic experience from the internal to the external, and enables immersion in day-to-day life, in other words, the external world.

This study’s limitations and recommendations for future research are as follows. First, participants in this study were limited to those who continuously participated in the cohort study, which signals an urgent need to access bereaved families who fall outside those who participate in regular psychological and physical health examinations. In the case of the bereaved family who did not participate in this study, it is necessary to keep in mind the possibility that they may have a different mental health state than that of the bereaved family who participated in this study. Therefore, considering this possibility, the results of this study should not be overgeneralized to all bereaved families. Also, in this context, a comparative study on the characteristics of the bereaved family group that received appropriate evaluation and intervention and the bereaved family group that did not should be performed in the future. Second, in this study, 23 interviewers were interviewed. Therefore, despite the standardized semi-structured interview procedure, it cannot be excluded that the characteristics of various interviewers may have influenced the qualitative content described by the interviewee. Third, in this study, data on the attitudes and impressions of the participants toward the interview were classified based on the data described by the interviewer. Therefore, the subjective experience of the interviewer may have influenced the research results. In future research, more objective evaluation and classification through video recording of interview scenes will be required. Forth, this study conducted qualitative analysis using a semi-structured questionnaire to investigate participants’ unique experiences and used χ2 testing to identify significant differences among subject characteristics. For more broad-scale quantitative data analyses, systematic comparative analysis with quantitative data is required to further elucidate the conditions of bereaved parents and those of survivors. Fifth, this study provided a window into the possibility of PTG by identifying positive changes in participants’ day-to-day lives after the accident. Our findings signal a need for further investigation and analysis of factors that facilitate PTG of trauma-affected individuals and psychological protective factors.

In conclusion, this study analyzed the unique experiences of bereaved parents and those of survivors 5 years after the Sewol Ferry accident. One-on-one interviews of 186 parents were conducted by 23 psychiatrists. Based on these interviews, we investigated the psychiatric, physical, and relational difficulties, and major personal and social changes, experienced by bereaved parents and survivors’ parents, and identified differences by gender. As such, the results of this study can provide a basis for continuing psychological evaluation and intervention. Long-term systematic psychosocial approaches that include providing social infrastructure, mental health services, and facilitating an individual’s process of recovery are needed and require the formulation of professional intervention guidelines.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download