INTRODUCTION

Human breast milk is essential for the growth and development of newborns and is an irreplaceable source of nutrition for early survival. It is well known that breast milk contains 87–88% water and provides 65–70 kcal per 100 mL through macronutrients such as carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

123 In addition, hormones and growth factors present in breast milk perform various bioactive functions.

2 In addition, the human health effects of immunologic components containing lactoferrin, lysozyme, secretory immunoglobulin A, etc., are also well known.

145 Therefore, the World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund recommends that mothers exclusively breastfeed their babies until 6 months of age, and recommend that they continue breastfeeding until they are 2 years old.

67 However, in modern society, various reasons prevent mothers from breastfeeding their children.

8 Social reasons such as increases in women's social activity, as well as the issues of diseases and people's negative perceptions regarding breastfeeding are increasing the difficulty of breastfeeding.

9 In an effort to improve the given situation and breastfeeding rate, each country and institution is enforcing various policies such as operating breast milk banks. Many companies are trying to support mothers’ breastfeeding in various ways, such as providing nursing rooms and break times. Korea, where welfare is relatively developed, still faces limitations in terms of policy support and changing people’s attitudes.

101112 These limitations exist in medical institutions that care for people's health. Mothers working for medical institutions are also responsible for the upbringing and health care of their children. Nevertheless, environmental factors such as special working conditions, lack of understanding of breastfeeding, and restless work at medical institutions exist for mothers working for medical institutions who cannot focus on breastfeeding.

Ironically, breastfeeding is particularly difficult for workers working at medical institutions in South Korea, which typically emphasize the advantages of breastfeeding and recommend breastfeeding. Nevertheless, research has not yet been conducted in South Korea about how breastfeeding policies are progressing in these institutions and what difficulties they may have encountered. Therefore, we investigated the situation of breastfeeding in medical institutions in South Korea to confirm and identify the need for policy support and to improve environments which hinder breastfeeding.

Go to :

METHODS

Questionnaire to check breastfeeding status

To investigate the status of breastfeeding of medical healthcare workers, we enrolled those who had childbirth experience within the last 5 years and wanted to participate in the survey. Online questionnaires were sent to 313 applicants on July 22 and 23, 2021, of which some answers were collected through e-mail, and online questionnaires were sent again on August 2, 2021, to applicants who did not answer. Questionnaire collection was closed on August 5, 2021, and questionnaires were answered by 179 applicants in total. Of these, 175 surveys were analyzed, with the exception of two questionnaires with insufficient answers, a case where a child was hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit, and a case where it had been more than 5 years since birth.

The questionnaire consisted of 40 questions in eight sections, which took approximately 5 minutes to complete (

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1BwUuhBBlGlh8OJiGE_TvUm62BdxSvojf2KI4Zw8BiOE/edit?ts=60d2a4d6). The questionnaires included information related to: the category and type of work performed in medical institutions, birth status, whether or not the parent understood and was educated in advance about breastfeeding, and whether or not they had a plan for breastfeeding right after birth. We also analyzed if the mothers had breastfed their children, the factors affecting breastfeeding, and the children’s medical histories.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). This survey on the status of breastfeeding was confirmed by frequency analysis, and the comparison of whether or not breastfeeding was carried out for more than 1 month was compared using cross-analyses and t-tests. A χ2 test was performed to examine the differences according to whether breastfeeding lasts for more than one month. Analysis of the duration of breastfeeding was compared using the t-test, ANOVA test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Mann-Whitney U test. The comparison between breastfeeding duration and continuous variables was conducted using correlation analysis. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong and the requirement for informed consent was waived (IRB No. KHNMC 2020-11-009).

Go to :

RESULTS

Demographic data

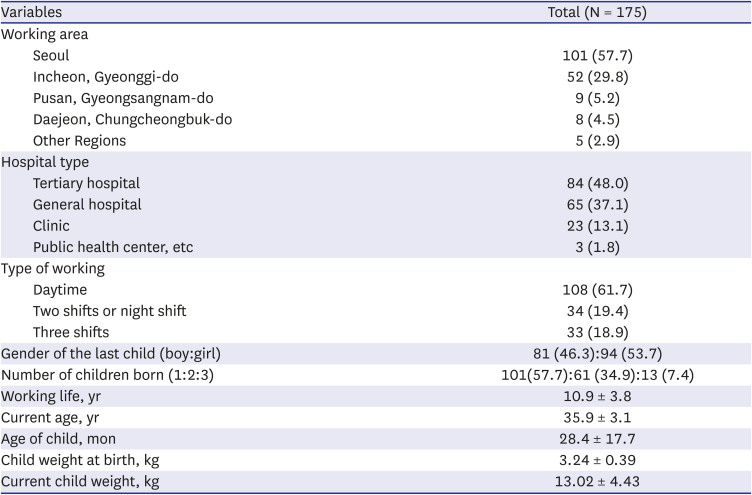

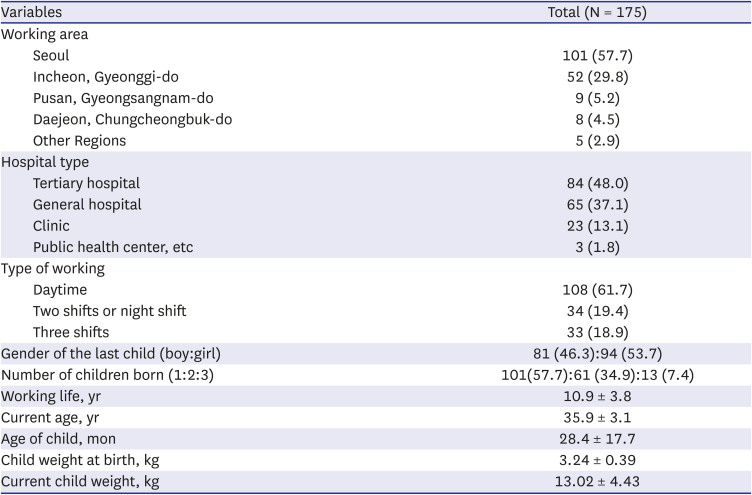

Table 1 and

Fig. 1 show the information related to work at medical institutions for the 175 participants included in the study. In terms of working areas, Seoul was the most common, with 101 people working (57.7%) in this region. Among the hospitals, 84 (48.0%) were working in advanced/upper general hospitals, 65 (37.1%) in general hospitals, and 23 (13.1%) in hospitals and clinics. In terms of occupation, 94 were doctors (53.7%), 71 were nurses (40.6%), and 10 were administrative personnel (5.7%). A total of 108 people (61.7%) worked in the daytime, 34 (19.4%) worked night duty along with daytime work or in two shifts, and 33 (18.9%) worked three different shifts. The number of girls birthed was higher (94, 53.7%) than boys (81, 46.3%), and the number of participants with one child was the highest at 101 (57.7%).

| Fig. 1Algorithm according to occupation of responders.

|

Table 1

Characteristics of responders

|

Variables |

Total (N = 175) |

|

Working area |

|

|

Seoul |

101 (57.7) |

|

Incheon, Gyeonggi-do |

52 (29.8) |

|

Pusan, Gyeongsangnam-do |

9 (5.2) |

|

Daejeon, Chungcheongbuk-do |

8 (4.5) |

|

Other Regions |

5 (2.9) |

|

Hospital type |

|

|

Tertiary hospital |

84 (48.0) |

|

General hospital |

65 (37.1) |

|

Clinic |

23 (13.1) |

|

Public health center, etc |

3 (1.8) |

|

Type of working |

|

|

Daytime |

108 (61.7) |

|

Two shifts or night shift |

34 (19.4) |

|

Three shifts |

33 (18.9) |

|

Gender of the last child (boy:girl) |

81 (46.3):94 (53.7) |

|

Number of children born (1:2:3) |

101(57.7):61 (34.9):13 (7.4) |

|

Working life, yr |

10.9 ± 3.8 |

|

Current age, yr |

35.9 ± 3.1 |

|

Age of child, mon |

28.4 ± 17.7 |

|

Child weight at birth, kg |

3.24 ± 0.39 |

|

Current child weight, kg |

13.02 ± 4.43 |

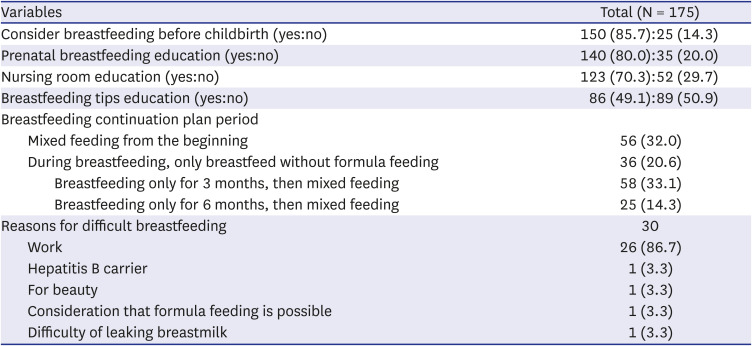

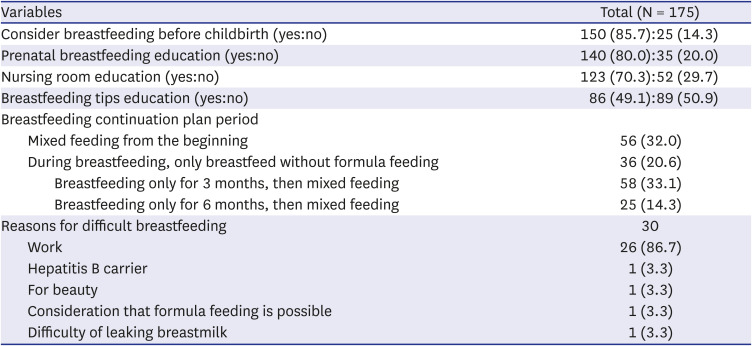

Table 2 shows the responses to breastfeeding before childbirth. Those who considered breastfeeding before childbirth (150 women, 85.7%) were more numerous than those who did not (25 women, 14.3%). A total of one hundred and forty women (80.0%) had received education about the benefits of breastfeeding before childbirth. However, only 86 women (49.1%) were educated on breastfeeding tips before childbirth, such as lactation or breastfeeding. The participants reported varying breastfeeding plans. Thirty people responded that they thought breastfeeding would be difficult, with 26 (86.7%) stating that this was due to work-related problems; the remaining 4 (13.3%) were concerned about their physical appearance or were hepatitis B carriers. The rest answered that they thought it would not matter or that their breast milk might not come out well.

Table 2

Information about breastfeeding before childbirth

|

Variables |

Total (N = 175) |

|

Consider breastfeeding before childbirth (yes:no) |

150 (85.7):25 (14.3) |

|

Prenatal breastfeeding education (yes:no) |

140 (80.0):35 (20.0) |

|

Nursing room education (yes:no) |

123 (70.3):52 (29.7) |

|

Breastfeeding tips education (yes:no) |

86 (49.1):89 (50.9) |

|

Breastfeeding continuation plan period |

|

|

Mixed feeding from the beginning |

56 (32.0) |

|

During breastfeeding, only breastfeed without formula feeding |

36 (20.6) |

|

|

Breastfeeding only for 3 months, then mixed feeding |

58 (33.1) |

|

|

Breastfeeding only for 6 months, then mixed feeding |

25 (14.3) |

|

Reasons for difficult breastfeeding |

30 |

|

Work |

26 (86.7) |

|

Hepatitis B carrier |

1 (3.3) |

|

For beauty |

1 (3.3) |

|

Consideration that formula feeding is possible |

1 (3.3) |

|

Difficulty of leaking breastmilk |

1 (3.3) |

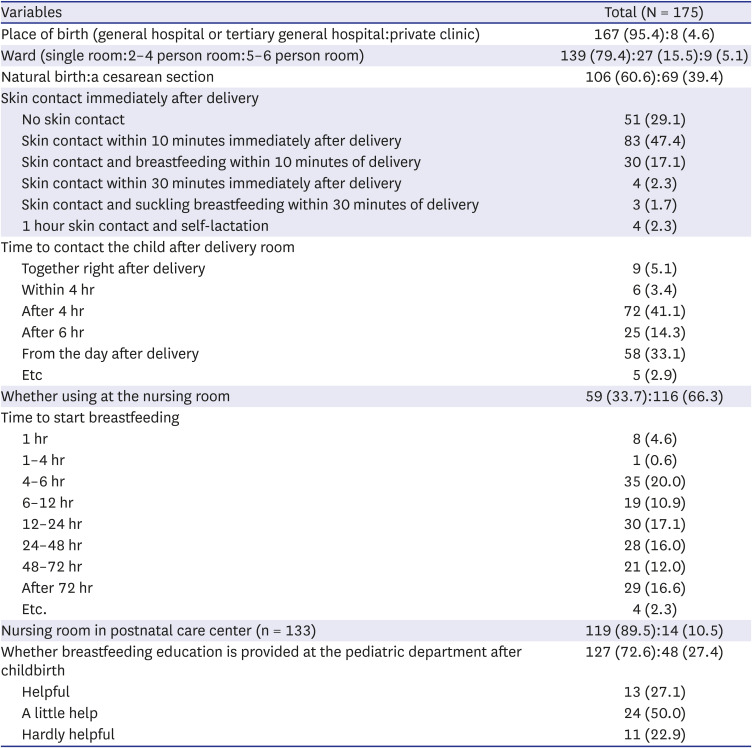

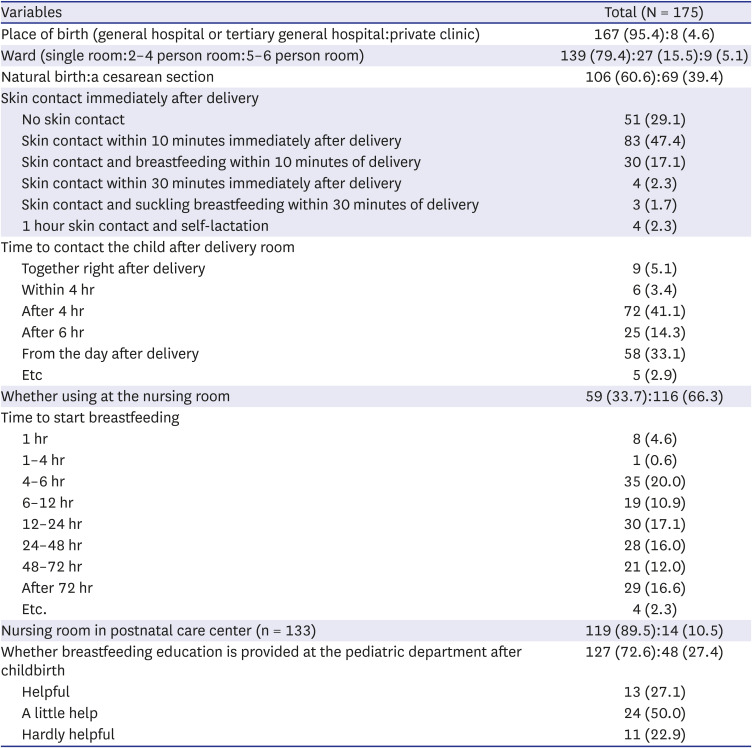

General hospitals accounted for 95.4% of births (167/175;

Table 3). Immediately after birth, as many as 51 mothers (29.1%) never tried skin contact, and 4 mothers (2.3%) only tried breastfeeding following skin contact with the baby for more than 1 hour. In terms of the time spent with the baby after birth, 9 mothers (5.1%) stayed with their babies right after birth, 6 were with them within 4 hours after birth, and 72 (41.1%) were with them from around 4–6 hour after birth. A total of 58 (33.1%) mothers began to spend time with their babies from the day after birth. As for breastfeeding, 8 mothers (4.6%) started within 1 hour, and 36 (20.6%) started within 6 hours. Twenty-eight (16.0%), 21 (12.0%), and 29 (16.6%) mothers started breastfeeding on the 1st, 2nd, or 3rd day after childbirth, respectively. Only 48 (27.4%) experienced guidance or education on breastfeeding from a pediatrician after childbirth. Among them, 13 (27.1%) answered that this education was useful, and 11 (22.9%) answered that it was hardly useful.

Table 3

Information about breastfeeding after childbirth

|

Variables |

Total (N = 175) |

|

Place of birth (general hospital or tertiary general hospital:private clinic) |

167 (95.4):8 (4.6) |

|

Ward (single room:2–4 person room:5–6 person room) |

139 (79.4):27 (15.5):9 (5.1) |

|

Natural birth:a cesarean section |

106 (60.6):69 (39.4) |

|

Skin contact immediately after delivery |

|

|

No skin contact |

51 (29.1) |

|

Skin contact within 10 minutes immediately after delivery |

83 (47.4) |

|

Skin contact and breastfeeding within 10 minutes of delivery |

30 (17.1) |

|

Skin contact within 30 minutes immediately after delivery |

4 (2.3) |

|

Skin contact and suckling breastfeeding within 30 minutes of delivery |

3 (1.7) |

|

1 hour skin contact and self-lactation |

4 (2.3) |

|

Time to contact the child after delivery room |

|

|

Together right after delivery |

9 (5.1) |

|

Within 4 hr |

6 (3.4) |

|

After 4 hr |

72 (41.1) |

|

After 6 hr |

25 (14.3) |

|

From the day after delivery |

58 (33.1) |

|

Etc |

5 (2.9) |

|

Whether using at the nursing room |

59 (33.7):116 (66.3) |

|

Time to start breastfeeding |

|

|

1 hr |

8 (4.6) |

|

1–4 hr |

1 (0.6) |

|

4–6 hr |

35 (20.0) |

|

6–12 hr |

19 (10.9) |

|

12–24 hr |

30 (17.1) |

|

24–48 hr |

28 (16.0) |

|

48–72 hr |

21 (12.0) |

|

After 72 hr |

29 (16.6) |

|

Etc. |

4 (2.3) |

|

Nursing room in postnatal care center (n = 133) |

119 (89.5):14 (10.5) |

|

Whether breastfeeding education is provided at the pediatric department after childbirth |

127 (72.6):48 (27.4) |

|

Helpful |

13 (27.1) |

|

A little help |

24 (50.0) |

|

Hardly helpful |

11 (22.9) |

Comparison to the group who continued breastfeeding for longer than a month or who did not

Of all the lactating mothers who participated in the questionnaires, 160 (91.4%) breastfed for more than a month, and 15 (8.6%) breastfed for less than a month (

Table 4). When breastfeeding was planned in advance, the mothers were more likely to continue breastfeeding for more than a month, compared to when it was not planned (

P = 0.101). Among 133 mothers who answered that they stayed with their babies in the same nursing room at a postnatal care center, 111 (93.3%) kept breastfeeding for more than a month, but among those who stayed apart, only 10 (71.4%) continued breastfeeding for more than a month (

P = 0.024). Additionally, a meaningful relationship was found between breastfeeding for more than a month and work shift patterns in medical institutions (

P = 0.027).

Table 4

Difference according to whether breastfeeding lasts for more than one month

|

Variables |

Breastfeeding for more than 1 month (n = 160) |

Breastfeeding for less than 1 month (n = 15) |

P value |

|

Working area |

|

|

0.862 |

|

Seoul (n = 101) |

90 (89.1) |

11 (10.9) |

|

Incheon, Gyeonggi-do (n = 52) |

50 (96.2) |

2 (3.8) |

|

Pusan, Gyeongsangnam-do (n = 9) |

8 (88.9) |

1 (11.1) |

|

Daejeon, Chungcheongbuk-do (n = 8) |

7 (87.5) |

1 (12.5) |

|

Other regions (n = 5) |

5 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Type of working hospital |

|

|

0.425 |

|

Tertiary general hospital (n = 84) |

75 (89.3) |

9 (10.7) |

|

General hospital (n = 65) |

63 (96.9) |

2 (3.1) |

|

Hospital (n = 23) |

20 (87.0) |

3 (13.0) |

|

Public health, others (n = 3) |

2 (66.7) |

1 (33.3) |

|

Occupation |

|

|

0.422 |

|

Doctor (n = 94) |

85 (80.4) |

9 (9.6) |

|

Nurse (n = 71) |

65 (91.5) |

6 (8.5) |

|

Administrative (n = 10) |

10 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Work type |

|

|

0.027*

|

|

Daytime (n = 108) |

95 (88.0) |

13 (12.0) |

|

Two shifts or night shift (n = 34) |

32 (94.1) |

2 (5.9) |

|

Three shifts (n = 33) |

33 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

Primiparity (n = 101):multiparity (n = 74) |

91 (90.1):69 (93.2) |

10 (9.9):5 (5.8) |

0.327 |

|

Pre-planned (or not) |

141 (94.0):19 (76.0) |

9 (6.0):6 (24.0) |

0.010*

|

|

Pre-education (or not) |

128 (91.4):32 (91.4) |

12 (8.6):3 (86.0) |

0.651 |

|

nursing room education (or not) |

112 (91.1):48 (92.3) |

11 (8.9):4 (7.7) |

0.524 |

|

Breastfeeding tips education |

78 (90.7):82 (92.1) |

8 (9.3):7 (7.9) |

0.472 |

|

Using nursing room after childbirth |

57 (96.6):103 (88.8) |

2 (3.4):13 (11.2) |

0.066 |

|

Nursing room in postnatal care center (n = 133) |

111 (93.3):10 (71.4) |

8 (6.7):4 (28.6) |

0.024*

|

|

Education by pediatricians |

41 (85.4):119 (93.7) |

7 (14.6):8 (6.3) |

0.078 |

Ninety-five (88.0%) daytime workers, 32 (94.1%) two-shift workers, and 33 (100%) three-shift workers continued breastfeeding for more than a month. Among these three shift types, a more significant difference was noticed in three-shift workers than in daytime workers (P = 0.026). However, breastfeeding durations greater than 1 month were not related to working area (P = 0.862), type of medical institution, or occupation.

It was also confirmed that there was no significant relationship with prior education about breastfeeding (P = 0.651), rooming-in systems implemented (P = 0.524), breastfeeding knowledge (P = 0.472), rooming-in after birth (P = 0.066), nor with whether prior education about breastfeeding was conducted by a doctor of pediatrics and adolescents after birth (P = 0.078). Whether this was a mother’s first birth (P = 0.327), the place of birth (P = 0.481), type of room (P = 0.633), way of birth (P = 0.648), and type of anesthesia provided at the time of giving birth (P = 0.332) were also not related.

A meaningful relationship between breastfeeding duration and skin contact with the baby, whether the baby was fed breast milk after birth (P = 0.190), the time until the mother met her baby again after birth (P = 0.121), and postnatal care location (P = 0.879) was also not found.

Characteristics in lactating mothers based on breastfeeding duration

Of the 160 lactating mothers who breastfed for over a month, the breastfeeding duration of 159 lactating mothers was analyzed, and the average breastfeeding duration was 5.51 ± 4.71 months (

Table 5). The maintenance period of breastfeeding was significantly longer when working in Seoul compared to in other areas (

P = 0.014). Breastfeeding durations also differed depending on the size or level of the hospitals (

P = 0.009); workers in general hospitals tended to breastfeed for significantly longer than those that worked in upper-level hospitals (4.5 ± 3.8 vs. 7.0 ± 5.5 months,

P = 0.003). A difference was also noted between occupation categories (

P = 0.019), but a more significant difference was found in the comparison between nurses and doctors, with nurses maintaining longer breastfeeding durations (4.7 ± 4.4 vs. 6.7 ± 5.1 months,

P = 0.012). Longer breastfeeding periods were noted when mothers worked three shifts compared to only working in the daytime (7.4 ± 5.6 vs. 5.3 ± 4.7 months,

P = 0.037) or working two shifts or on night duty (7.4 ± 5.6 vs. 4.1 ± 2.9 months,

P = 0.005).

Table 5

Difference according to the duration (period) of breastfeeding

|

Variables |

Values |

P value |

|

Working area (n = 159) |

|

|

|

|

|

Seoul (89):Incheon & Gyeonggi (50):others (20) |

6.3 ± 4.9 |

4.7 ± 4.5 |

4.1 ± 3.9 |

0.014*

|

|

Type of working hospital (n = 157) |

|

|

|

|

|

Tertiary general hospital (74):general hospital (63):hospital (20) |

4.5 ± 3.8 |

7.0 ± 5.5 |

5.1 ± 3.9 |

0.009*

|

|

Occupation (n = 159) |

|

|

|

|

|

Doctor (84):nurse (65):administrative (10) |

4.7 ± 4.4 |

6.7 ± 5.1 |

4.7 ± 2.4 |

0.019*

|

|

Work type (type of work) (n = 159) |

|

|

|

|

|

Daytime (95):day and night (31):three shifts (33) |

5.3 ± 4.7 |

4.1 ± 2.9 |

7.4 ± 5.6 |

0.015*

|

|

Breastfeeding planning, yes (n = 140) vs. no (n = 19) |

5.6 ± 4.8 |

5.0 ± 4.0 |

0.759 |

|

Breastfeeding education, yes (n = 127) vs. no (n = 32) |

6.0 ± 5.0 |

3.5 ± 2.8 |

0.000*

|

|

Parent-child (nursing) room education, yes (n = 111) vs. no (n = 48) |

6.1 ± 5.0 |

4.3 ± 3.7 |

0.015*

|

|

Education on breastfeeding tips, yes (n = 77) vs. no (n = 82) |

5.9 ± 5.1 |

5.2 ± 4.3 |

0.373 |

|

Duration for considering to continue breastfeeding |

|

|

0.002*

|

|

Mixed from the beginning (48):keep breastfeeding while coming out (34) |

4.0 ± 2.6 |

8.8 ± 6.5 |

|

Up to 3 months of breast milk (54):breast milk up to 6 months (23) |

4.5 ± 3.9 |

6.1 ± 4.6 |

|

Breastfeeding up to 6 months |

|

|

0.000*

|

|

Full (exclusive) breastfeeding (26):constant ratio mixed breastfeeding (19) |

10.7 ± 4.6 |

4.7 ± 2.8 |

|

Mainly formula feeding (57):predominantly breastfeeding (42) |

2.8 ± 1.5 |

7.6 ± 5.5 |

Depending on the period planned for breastfeeding prior to childbirth, the actual breastfeeding maintenance period after birth showed a significant difference (P = 0.002). Breastfeeding durations were longer when the mothers had planned to breastfeed exclusively without powdered milk supplementation (8.8 ± 6.5 months) or had planned to breastfeed for 6 months (6.1 ± 4.6 month) compared to those that planned to breastfeed for only 3 months (4.5 ± 3.9 month) or planned to breastfeed and use powdered milk from the start (4.0 ± 2.6 month). Those who kept breastfeeding for up to 6 months tended to continue for longer (P < 0.001).

On the other hand, childbirth experience (P = 0.219), child’s sex (P = 0.082), or whether breastfeeding was planned (P = 0.759) was not related to breastfeeding duration. The work period/employment period (P = 0.085), age of the lactating mother (P = 0.060), age at the time of childbirth (P = 0.335), and number of children (P = 0.111) also had no significant relationship.

In addition, the place of childbirth (P = 0.102), room used in the hospital after birth (P = 0.628), method of childbirth (P = 0.795), type of anesthesia (P = 0.252), time in skin contact with baby (P = 0.171), rooming-in (P = 0.339), initial time of breastfeeding (P = 0.773), place for postnatal care (P = 0.969), and rooming-in condition at the postnatal care center (P = 0.686) had no significant relationships with breastfeeding duration.

Whether or not a doctor of pediatrics and adolescents educated the mothers on breastfeeding after birth (P = 0.184) nor the mothers’ level of satisfaction from the education (P = 0.530) were related to breastfeeding duration. Meaningful results were not observed between breastfeeding duration and whether breastfeeding was maintained for 6 months, nor between medical history or if a mother had been hospitalized.

Factors hindering breastfeeding and potential countermeasures

Of the 15 mothers who stopped breastfeeding within a month, 4 (26.7%) had breastfed a previous child, 10 (66.7%) fed their first child, and 1 never breastfed their children. The reasons for not breastfeeding were as follows: multiple checks allowed, work-related reasons for six mothers (40%), not producing well for five (33.3%), lack of sleep for five (33.3%), baby not latching well for three (20.0%), and beauty reasons for two mothers (13.3%). Seven (46.7%) answered that breastfeeding-friendly circumstances at work are required for comfortable/stable breastfeeding, and 6 (40.0%) said that they needed the support of helpers for a certain period of time after birth. Out of a total of 160 lactating mothers who breastfed for over a month, valid answers about the type of breastfeeding they performed were obtained from 145, of which 27 (18.6%) exclusively breastfed for 6 months, and 42 fed their babies mainly breast milk along with other choices for 6 months.

With regard to the start time of weaning off breast milk, out of 158 who provided valid answers, 17 (10.8%) had started already or were going to start after 4 months, 57 (36.1%) planned to or did after 5 months of breastfeeding, 71 (44.9%) did after 6 months, and 13 (8.2) started weaning their children after 6 months or were considering it.

A total of 112 mothers responded to the question regarding difficulties in breastfeeding after returning to work in a medical institution. Of these, 87 (77.7%) mentioned a lack of time caused by being busy at work, 82 (73.2%) mentioned the need for places and appropriate circumstances for breast pumping and storage, 22 (19.6%) mentioned unfavorable looks and attitudes from other people (1.9%). 19 (17.0%) were concerned regarding the nutrition of their breast milk.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Although the importance and benefits of breastfeeding are well known, the breastfeeding rate has decreased for various reasons in modern society. For this reason, various studies have been conducted to identify these causes and improve breastfeeding rates.

8911 In Korea, various investigations on the causes of breastfeeding have been conducted.

1314 There have been studies on the relation between breastfeeding and the work of breastfeeding mother, but there have been no studies in various occupations working in medical institutions.

1516

This is the first study in South Korea to investigate breastfeeding among mothers working in medical institutions with a variety of occupations, working hours, and working patterns. Through this study, we acquired data concerning awareness regarding breastfeeding of healthcare workers and whether education was provided to them. In addition, by investigating the status of workers in medical institutions who have experienced breastfeeding or are currently breastfeeding, we analyzed the factors affecting them and identified potential areas for improvement.

The researchers identified several interesting findings in this study. First, it was confirmed that there was a difference in breastfeeding period according to the type of work. We found a tendency to maintain longer-term breastfeeding when working at a general hospital rather than at a tertiary center. In addition, compared to doctors who worked daytime shifts, they tended to maintain longer-term breastfeeding in nurses that worked three shifts. In this regard, we were not able to carry out further research into special work circumstances depending on the respective hospitals or departments. However,-compared to the mode of working regularly only during daytime hours every day and returning to work the next day, even if the working hours or the number of days are irregular, it is possible to continue breastfeeding for a longer time because it is easier to breastfeed and store breast milk. However, compared to working exclusively in the daytime, it is possible that having more time at home, even if working irregularly in terms of time and days, makes pumping and saving breast milk more convenient and leads to a longer period of breastfeeding. Preceding research has confirmed that maternal employment status is related to the maintenance of breastfeeding; in addition, we confirmed that maintenance of breastfeeding depends on the shift pattern worked, even within the same occupational category.

151617

Second, we learned that it was not easy to continue breastfeeding after returning to work after maternity leave. Improving these circumstances is required, and lactating mothers also expressed the need for support. Even though there is a lack of understanding about breastfeeding in public places, our research found that this concern does not exacerbate breastfeeding difficulties.

1819 Recently, medical institutions have provided places in outpatient departments or other available places where visitors are able to feed or pump breast milk. Nevertheless, it was confirmed that there are still not enough facilities or support for workers themselves. There has been noticeable improvement in the support systems created for mothers and children immediately after birth in South Korea. Childcare support policies, such as maternity leave or others, are being established, and specialized facilities such as postnatal care centers or postnatal helper services are also available. Infant care facilities, such as childcare centers, have been improved. However, there is still a lack of support for lactating mothers and for infants who are at the stage between newborn and child. The facilities and support policies provided for lactating and working mothers are still in the beginning stages.

Third, we realized that sufficient education and planning prior to childbirth is important for maintaining breastfeeding. The importance of education related to breastfeeding has already been emphasized not only for workers at medical institutions but also for other lactating mothers.

9131420 However, our study, which is different from previous studies, showed that education after childbirth has little relevance to the maintenance of breastfeeding. This could be more related to a mother’s satisfaction level of the education received. Unfortunately, due to the lack of experts that can appropriately educate mothers on breastfeeding in the country, satisfaction levels are currently expected to remain low.

Further, most of the education about breastfeeding that is provided by experts is carried out shortly after childbirth only, and in many cases, the education before giving birth depends on the surrounding information. In particular, no single expert can teach parents continuously after the neonate stage. Providing continuous education about the benefits and appropriate methods of breastfeeding to lactating mothers who regularly visit pediatric departments before childbirth and at every vaccination appointment is necessary. To achieve this, we confirmed the necessity of trained experts/specialists, as well as proper systems and support. Since the continuity of breastfeeding eventually depends on the will of the lactating mothers, improving awareness through continuous education in advance of childbirth is urgently required.

14 Finally, there are guidelines to help mothers and babies feel emotional bonds at the initial stage, such as physical skinship or allowing the baby to suckle immediately after giving birth; however, we confirmed these have been cursory yet.

Our study has a few limitations. It was not a mass survey encompassing all occupational categories at the respective medical institutions located in all areas nationwide. Since the questionnaire was answered by the people willing to, there are limitations to the sample size and in the occupational categories and areas considered. In addition, it was not easy to accurately reflect the diversity of duties according to the respective department, detailed occupations, and various individual differences in our sample.

It is known that breastfeeding durations may differ depending on external factors such as the type of childbirth or medical history; however, we failed to confirm meaningful results from our limited survey data.

921 Nevertheless, the research enabled us to learn about the actual breastfeeding conditions of workers at medical institutions. Furthermore, to better encourage breastfeeding, we highlighted the need for circumstance improvement in medical institutions, the implementation of supporting policies, and the provision of specialized education on breastfeeding.

In conclusion, we found that breastfeeding durations of workers in medical institutions vary according to their work hours or shift patterns, and there is a need for support in this environment, including facilities or policies to enable the continuation of breastfeeding after returning to work. In addition, we confirmed that it is necessary to maintain the will to keep breastfeeding through continuous education prior to childbirth and to train experts and specialists to continue this education after childbirth.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download