2. Golinelli D, Boetto E, Carullo G, Nuzzolese AG, Landini MP, Fantini MP. Adoption of digital technologies in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review of early scientific literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020; 22:e22280. PMID:

33079693.

3. Kataria S, Ravindran V. Digital health: a new dimension in rheumatology patient care. Rheumatol Int. 2018; 38:1949–1957. PMID:

29713795.

4. Kim HS. Apprehensions about excessive belief in digital therapeutics: points of concern excluding merits. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35:e373. PMID:

33230984.

5. Shim JS, Oh K, Jung SJ, Kim HC. Self-reported diet management and adherence to dietary guidelines in Korean adults with hypertension. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:432–440. PMID:

32096363.

6. Cheung BMY, Or B, Fei Y, Tsoi MF. A 2020 vision of hypertension. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:469–475. PMID:

32281321.

7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Enforcement policy for digital health devices for treating psychiatric disorders during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) public health emergency [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration;2020. cited 2021 March 27. Available from:

https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.

8. Gesetzesbeschluss des Deutschen Bundestages (Legislature, German Federal Parliament). Gesetz für eine bessere Versorgung durch Digitalisierung und Innovation (Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz - DVG) (Nov. 29, 2019).

11. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte. DiGA [Internet]. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte;2021. cited 2021 May 27. Available from:

https://diga.bfarm.de/.

12. CureApp, Inc. CureApp hypertension therapeutics app clinical trial results announced at ESC congress 2021 and published in the European Heart Journal, a leading cardiovascular journal [Internet]. Tokyo: CureApp, Inc.;2021. cited 2021 September 22. Available from:

https://cureapp-en.blogspot.com/.

13. Jeon YW, Kim HC. Factors associated with awareness, treatment, and control rate of hypertension among Korean young adults aged 30–49 years. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:1077–1091. PMID:

32975054.

14. Lee HY, Oh GC, Sohn IS, et al. Suboptimal management status of younger hypertensive population in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:598–606. PMID:

34085433.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Policy for device software functions and mobile medical applications [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration;2019. cited 2021 March 27. Available from:

https://www.fda.gov/media/80958/download.

20. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Guidelines for medical device applicability of the program [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2021. cited 2021 April 13. Available from:

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11120000/000764274.pdf.

21. Australian Therapeutic Goods Act 1989, Pub. L. No. 21, 1990 (Jan 1, 2019).

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technology (MCIT) and definition of “Reasonable and Necessary”; Delay of effective date. Final rules. Fed Regist. 2021; 86:26849–26854.

25. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technology (MCIT) and definition of “Reasonable and Necessary.” Final rules. Fed Regist. 2021; 86:2987–3010.

26. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technology (MCIT) and definition of “Reasonable and Necessary.” Final rules. Fed Regist. 2021; 86:62944–62958.

30. Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss Innovationsausschuss. Forderbekanntmachung Seite des Innovationsausschusses beim Gemeinsamen Bundesausschuss zur themenoffenen Forderung von neuen Versorgungsformen gemaß § 92a Absatz 1 des Fuften Buches Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB V) zur Weiterentwicklung der Versorgung in der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung (zweistufiges Verfahren) [Internet]. Berlin: Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss Innovationsausschuss;2021. cited 2021 April 13. Available from:

https://innovationsfonds.g-ba.de/downloads/media/245/2021-03-17_Foerderbekanntmachung_NVF_themenoffen_2021.pdf.

31. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. DX (Digital Transformation) action strategies in healthcare for SaMD (Software as a Medical Device) [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2020. cited 2021 April 13. Available from:

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11124500/000737470.pdf.

34. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Roles and functions of health insurance review and assessment service [Internet]. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2021. cited 2021 May 25. Available from:

https://repository.hira.or.kr/handle/2019.oak/2523.

35. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Guidelines on national health insurance benefits coverage for new and innovative healthcare technology. AI-based healthcare technology (medical imaging) & introduction of 3D printing to healthcare technology [Internet]. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2019. cited 2021 May 25. Available from:

https://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA020041000100&brdScnBltNo=4&brdBltNo=10255#none.

36. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; revised process for making national coverage determinations. Notice. Fed Regist. 2013; 78:48164–48169.

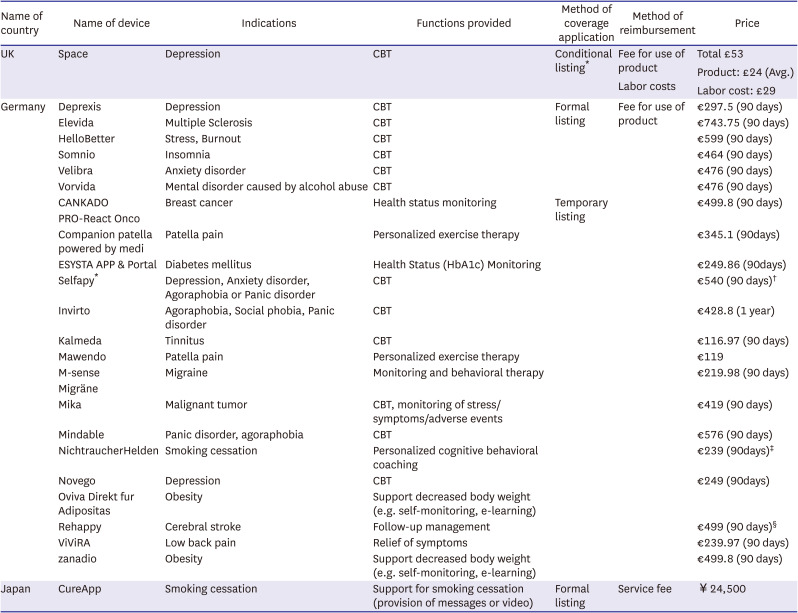

42. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte. DiGA directory [Internet]. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte;2021. cited 2021 May 27. Available from:

https://diga.bfarm.de/de/verzeichnis.

43. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Handling of medical device insurance coverage, etc. [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2019. cited 2021 April 13. Available from:

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000497471.pdf.

44. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Criteria for calculating insurance redemption prices for specified insurance medical materials [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2019. cited 2021 April 13. Available from:

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000497470.pdf.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download