INTRODUCTION

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) Type II, known as causalgia, develops after a nerve injury, and tends to show the more painful and more severe symptoms of CRPS. The ordinary strategy in CRPS treatment is often multi-disciplinary, with the use of various kinds of medications and physical therapies combined with sympathetic nerve block. Even with several treatments, it is very difficult to manage the acute stage of CRPS type II. And neurostimulation (spinal cord stimulator) could be surgically implanted to control the pain by directly stimulating the spinal cord for the treatment of intractable CRPS. A systematic review concluded that spinal cord stimulation appears to be an effective therapy in the management of patients with CRPS type I (Level A evidence) than type II (Level D evidence)14). Moreover, there is evidence to reveal that SCS is a cost-effective treatment for CRPS type I. We report a case of acute stage CRPS type II treated with new anti-inflammatory agent [polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) solution]. Result was very satisfactory. As far as we know, this is 1st case report showing effectiveness of PDRN for the treatment of CRPS type II.

CASE REPORT

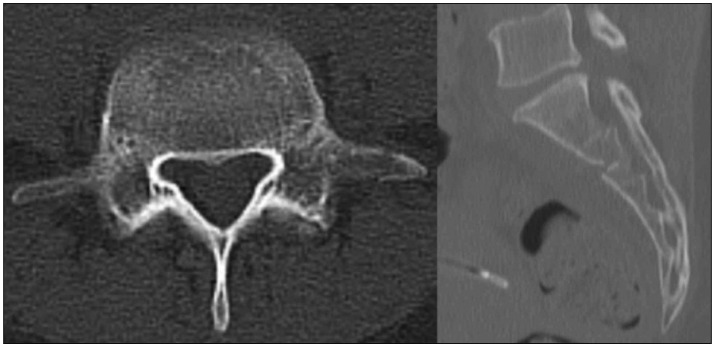

A 32-year-old female patient came to the hospital complaining of left leg numbness. She had experienced a traumatic event, a fall into a waterway, one month ago. After which, she had severe low back pain and was evacuated to the nearby general hospital. Computed tomography (CT) showed an L5 left transverse process fracture and an S2 body fracture, and absolute bed rest (ABR) for one month was recommended (Fig. 1). During this period, her left leg numbness was progressively aggravated. To evaluate whether symptom aggravation during the ABR period was related to the patient's history of a left-side L5–S1 discectomy 2 years previously, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. The MRI did not show recurrent disc material, but it did show an annular tear at L4–5 and postoperative scar tissue at L5–S1, and the previous doctor recommended continued conservative management. After the period of ABR was complete, the patient began ambulation and was transferred to our hospital in her hometown. She complained of left leg numbness initially upon arrival, and the more she walked, the more the pain was aggravated, showing hyperalgesia and allodynia.

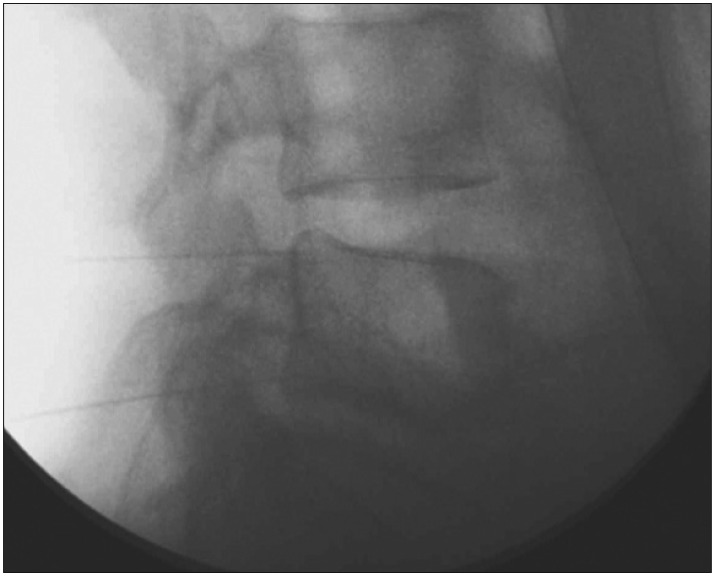

Gabapentin and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors are prescribed to treat these neuropathic symptoms. And we ordered physiotherapy and wheelchair ambulation for the first two weeks. Various nerve blocks were performed, including sympathetic nerve block. Even as the symptoms seemed to subside somewhat, skin flushing still appeared on the left lower leg when the patient was in a standing position (Fig. 2). The persistent skin discoloration seemed to worsen as time went on, despite frequent sympathetic nerve blocks using steroid. The allodynia became so severe that the patient was hesitant to wear a sock. To rule out the possibility of arterial injury, we performed lower extremity CT angiography, and there was no sign of arterial injury around the fracture site. We concluded that her symptoms resulted from lumbosacral plexus injury due to the transverse process fracture. At that time, it was 2 months after the initial trauma. Because this was the acute phase, we wanted to prevent the disease from progressing to the chronic phase. Our clinics have been performing prolotherapy using PDRN solution, and we are familiar with the effects of PDRN. We injected PDRN solution at the ventral surface of the left L5 transverse process, superior and inferior, one ampoule (3 cc) each by using needles used for medial branch block (Fig. 3). Needles was inserted perpendicularly through C-arm-guided approach.

Allodynia and hyperalgesia were improved one day after the procedure and the skin flushing was diminished (Fig. 4). The patient was discharged 3 days after the PDRN injection and at the 1-month follow-up, her symptoms were very much improved.

DISCUSSION

Autonomic disturbance can lead to significant pain in patients with peripheral nerve injuries and is characteristic of CRPS. Severe burning pain, allodynia, hyperalgesia, careful attempts to protect the involved extremity from movement or contact, and evidence of autonomic hyper- or hypoactivity are features of CRPS. Vascular changes such as skin flushing and discoloration and temperature fluctuations are hallmarks of this deranged autonomic activity. CRPS type I usually occurs after a minor injury to the extremity (e.g., ankle sprain), whereas CRPS type II occurs after significant injury to a major mixed nerve (e.g., brachial plexus injury), such as in our case.

CRPS may change within a patient over time, particularly in the transition from "warm CRPS" (acute) to "cold CRPS" (chronic)5). Several pathophysiological concepts have been proposed to explain the complex symptoms of CRPS : 1) facilitated neurogenic inflammation; 2) pathological sympatho-afferent coupling; and 3) neuroplastic changes within the CNS11). The acute CRPS stage is regarded as the inflammatory period.

Management of CRPS remains challenging, with many patients having only partial or minimal relief with treatment. Therapy is based on a multidisciplinary approach. Non-pharmacological approaches include physiotherapy and occupational therapy. Pharmacotherapy is based on individual symptoms and includes steroids, free radical scavengers, antineuralgic agents, and finally agents interfering with bone metabolism (calcitonin, bisphosphonates). Invasive therapeutic options include sympathectomy and implantation of spinal cord stimulators11).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, and free radical scavengers are used in CRPS with intent to treat for pain as well as for inflammation. However, CRPS-related inflammation may be largely neurogenic, initiated by inflammatory mediators from the terminals of afferent nociceptors, and no drugs have been studied for this type of inflammation8). Hence, there is no satisfactory pharmaceutical intervention for the acute phase of CRPS. Many interventional therapies for pain relief have been tried for decades. Sympathetic nerve block is traditionally recognized as an important procedure, both in the diagnosis and treatment of CRPS. The pain relief following sympathetic nerve block generally outlasts the effect of the local anesthetic13). If after numerous therapies, a patient's pain is intractable, sympathectomy or spinal cord stimulation (SCS) may be recommended as surgical treatment alternatives. Recently, SCS seems to be the general trend, and it is reported that SCS is effective in reducing the chronic neuropathic pain of CRPS type I914). Specific treatment of CRPS type II at the chronic stage is also reported, but to our knowledge, no specific interventional or invasive treatment for control of acute stage CRPS type II has been reported6).

PDRN (Placentex®) is a low molecular weight DNA complex extracted from trout sperm. PDRN is selectively coupled with the adenosine A2A receptor and acts as an agonist. The adenosine A2A receptor alters the cytokine system by decreasing secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, macrophage inflammatory protein 1α, and interleukin (IL)-6. The adenosine A2A receptor is also associated with increased circulation of IL-10, anti-inflammatory cytokine4). Therefore, PDRN has an anti-inflammatory effect and could be a potential pharmacological treatment for inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis315). This also explains how PDRN can help to control the acute phase of CRPS, such as in our case. However, this doesn't seem to be enough to explain the dramatic result of our case.

The adenosine A2A receptor also has a tissue regeneration effect, as indicated by its stimulation of endothelial cell migration and proliferation. Activation of this receptor is also associated with increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, which enhances tissue function712). Promoting cell proliferation by acting as a mitogen for fibroblasts and, endothelial cells could result in extracellular matrix production and remodeling, and can be useful for burn treatment and prolotherapy210). We suppose that this regeneration mechanism has an additional effect on our case. Because we have been performing prolotherapy in our clinics, we have observed these mechanisms of PDRN, not only the regeneration effect, but also the anti-inflammatory effect. PDRN has been found to be a safe modality, and no harmful effect has been reported1).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download