Abstract

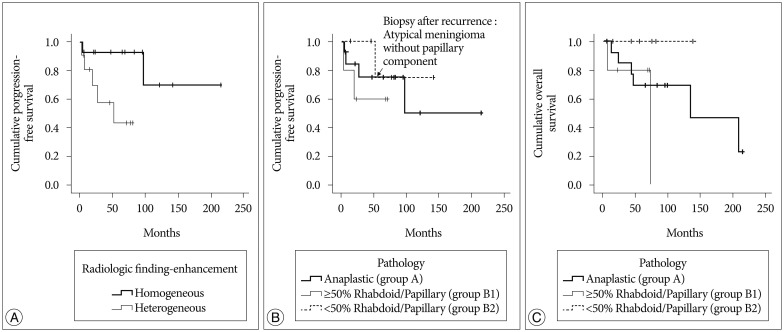

Papillary and rhabdoid meningiomas are pathologically World Health Organization (WHO) grade III. Any correlation between clinical prognosis and pathologic component is not clear. We analyzed the prognoses of patients with meningiomas with a rhabdoid or papillary component compared to those of patients with anaplastic meningiomas. From 1994 to June 2013, 14 anaplastic meningiomas, 6 meningiomas with a rhabdoid component, and 5 meningiomas with papillary component were pathologically diagnosed. We analyzed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, extent of removal, adjuvant treatment, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and pathologic features of 14 anaplastic meningiomas (group A), 5 meningiomas with a predominant (≥50%) papillary or rhabdoid component (group B1), and 6 meningiomas without a predominant (<50%) rhabdoid or papillary component (group B2). Homogeneous enhancement on MRI was associated with improved PFS compared to heterogeneous enhancement (p=0.025). Depending on pathology, the mean PFS was 134.9±31.6 months for group A, 46.6±13.4 months for group B1, and 118.7±19.2 months for group B2. The mean OS was 138.5±24.6 months for group A and 59.7±16.8 months for group B1. All recurrent tumors were of the previously diagnosed pathology, except for one tumor from group B1, which recurred as an atypical meningioma without a papillary component. Group B1 tumors showed a more aggressive behavior than group B2 tumors. In group B2 cases, the pathologic findings of non-rhabdoid/papillary portion could be considered for further adjuvant treatment.

Meningiomas are the most common type of primary intracranial or spinal tumors10). The majority of meningiomas are benign, with malignant meningiomas comprising only 1 to 2% of all diagnoses. In the current World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, benign meningiomas are recognized by their histologic subtype and lack of anaplastic features10). WHO grade III malignant meningiomas have rhabdoid or papillary subtypes, histological features of frank malignancy resembling that of carcinomas, melanomas, or high-grade sarcomas, or 20 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPFs)10).

Meningiomas with rhabdoid or papillary components are aggressive clinically and biologically, leading to high mortality46815). All patients with malignant meningiomas have poor prognoses, but neither clinical courses nor pathologic and radiologic characteristics of rhabdoid or papillary meningiomas are known due to low incidences1).

In this study, meningiomas with rhabdoid or papillary components were divided into two groups, those with and without predominant rhabdoid or papillary components. We analyzed clinical, radiologic, and pathologic findings in patients with meningiomas with and without predominant rhabdoid or papillary components and compared those findings to those for anaplastic meningiomas.

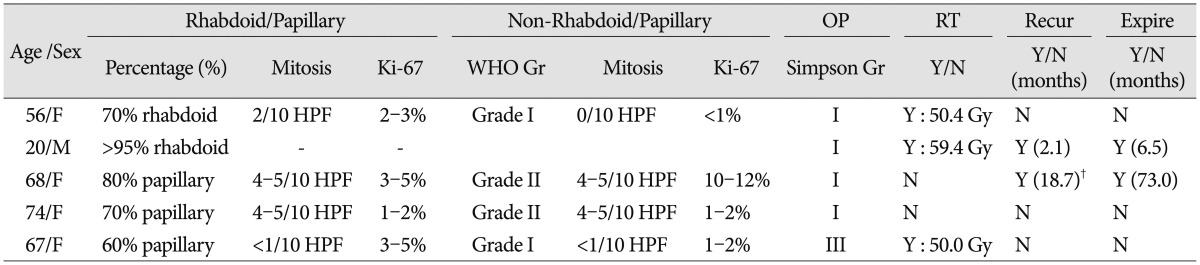

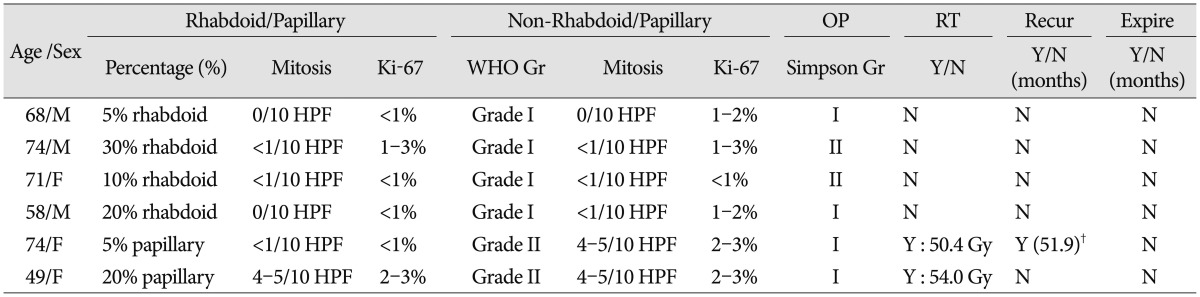

Twenty-five patients were diagnosed with malignant meningiomas from 1994 to June 2013. This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board (IRB No: CNUHH-2015-100), and the need for written informed consent was waived. Pathologic diagnoses, according the WHO classification, were anaplastic meningioma (n=14), meningioma with a rhabdoid component (n=6), and meningioma with a papillary component (n=5)10). The meningiomas with a rhabdoid or papillary component (total=11) were further divided into meningiomas with a predominant (≥50%) rhabdoid (n=2) or papillary (n=3) component and meningiomas without a predominant (<50%) rhabdoid (n=4) or papillary (n=2) component. In total, all patients were divided into three groups. Group A patients had anaplastic meningiomas. Patients with meningiomas containing a predominant (≥50%) papillary or rhabdoid component were in group B1, and patients with meningiomas not containing a predominant (<50%) rhabdoid or papillary component were in group B2.

The mean age of the patients was 52.9 years (range, 20–74 years), and there were 15 women and 10 men. The mean symptom duration was 3.4 months (range, 0.1–12 months). The main clinical symptoms included headache in 12 patients, nausea and vomiting in 3 patients, seizures in 4 patients, altered mental state in 4 patients, hemiparesis in 1 patient, and visual disturbance in 1 patient. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) scale (0 to 3) was used to assess patients before and after surgery14). Pre-operative ECOG PS scores were 0 in 8 patients, 1 in 8 patients, 2 in 7 patients, and 3 in 2 patients.

Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed with gadolinium enhancement. Lesions were classified according to size, location, severity of peri-tumoral edema (none, mild, moderate, or severe), shape of tumor (well circumscribed or mushroom pattern), signal intensity (low, iso, or high) on T2-weighted images (T2WI), and enhancement pattern (homogeneous or heterogeneous). Mild peri-tumoral edema measured less than half of the longest tumor diameter on the axial view; moderate edema measured more than half, but less than twice and severe edema measured more than twice.

The extent of tumor removal was estimated by the Simpson grading system and was primarily determined according to the judgment of the neurosurgeons. The extent of tumor removal was validated by reviewing post-operative gadolinium-enhanced computed tomography scans16). After surgery, patients underwent follow-up gadolinium-enhanced MRI every 6 months. New lesion development or remnant mass enlargement was considered recurrence.

We defined the mean range as the follow-up length and determined the effects of single variables on progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) via univariate and multivariate analyses. The variables were radiologic parameters, extent of removal, pathologic subtype, and adjuvant treatment. PFS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of radiological progression or last follow-up visit, and OS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death or last follow-up. We calculated survival probability using the Kaplan-Meier method and performed comparisons using the log-rank test. We examined all variables using the Cox proportional hazard analysis to identify independent predictors of survival. All statistical analyses were performed at a significance level of p<0.05 using the statistical package SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Among the 14 group A anaplastic meningiomas, the mean tumor size was 4.1 cm (range, 1.1–8.8 cm). The mass was in the convexity in 6 patients, in the parasagittal area in 4 patients, at the sphenoid ridge in 3 patients, and at the jugular foramen in 1 patient. Three patients had mild peri-tumoral edema, 6 patients moderate edema and 2 patients severe edema. Tumors were well-circumscribed in 13 of 14 patients. T2WI signal intensity was low for 4 tumors, iso for 5 tumors, and high for 5 tumors, with 9 tumors having homogenous enhancement and 5 having heterogeneous enhancement. Among the 5 group B1 meningiomas with ≥50% rhabdoid or papillary component, the mean size of tumor was 2.9 cm (range, 0.7–5.7 cm). The mass was in the convexity in 3 patients, in the parasagittal area in 1 patient, and periventricular in 1 patient. Peri-tumoral edema was present in 4 of 5 patients (1 mild, 2 moderate, and 1 severe), and 4 of the 5 tumors were well-circumscribed. The T2WI signal was low for 2 tumors, iso for 1 tumor, and high for 2 tumors, with 2 tumors having homogenous enhancement and 3 having heterogeneous enhancement. Among the 6 group B2 meningiomas with <50% rhabdoid or papillary component, the mean tumor size was 3.15 cm (range, 2.1–4.4 cm). The mass was in the convexity in 3 patients, in the parasagittal area in 1 patient, in the periventricular in 1 patient, and in the olfactory groove in 1 patient. There was peri-tumoral edema in 5 of 6 patients (mild in 3, moderate in 1, and severe in 1). Tumors were well-circumscribed in 6 patients. The T2WI signal intensity was low for 2 tumors, iso for 1 tumor, and high for 3 tumors. Four of the tumors had homogenous enhancement, and 2 had heterogeneous enhancement.

Gross total resections, which were Simpson grades I and II, were achieved in 24 (grade I, n=18; grade II, n=6) of the total 25 patients (96%). The remaining patient (n=1) had a Simpson grade III resection. The post-operative ECOG PS scores were 0 in 8 patients, 1 in 8 patients, 2 in 7 patients, and 3 in 2 patients. Post-operative complications included the low cranial nerve symptoms of swallowing difficulty in 1 patient, seizures in 1 patient, hemiparesis in 2 patients, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage in 2 patients.

Among group A patients (n=14), Simpson grade I resection was achieved in 10 patients, and grade II resection was achieved in 4 patients. All 14 patients in this group received adjuvant radiotherapy (mean dose, 54.2 Gy; range, 36.0–60.0 Gy). Among group B1 patients (n=5), Simpson grade I resection was achieved in 4 patients, and grade III resection was achieved in 1 patient because of tumoral adhesion to cranial nerves. Three of 5 patients received post-operative radiotherapy (mean dose, 53.3 Gy; range, 50.4–59.4 Gy). Two patients refused radiotherapy because of their old age. Among group B2 patients (n=6), Simpson grade I resection was achieved in 4 patients, and grade II resection was achieved in 2 patients. Two patients received adjuvant radiotherapy (mean dose, 52.2 Gy; range, 50.4–54.0 Gy) because of atypical meningioma in the non-rhabdoid/papillary portion.

Among all 25 patients with meningiomas, the mean follow-up duration was 72.5 months (range, 5.6–214.9 months). The mean PFS was 49.9±12.1 months, and the mean OS was 59.7±16.8 months.

With respect to radiologic tumor characteristics (Table 1), homogenous enhancement was associated with better PFS (172.3±26.8 months) than heterogeneous enhancement (48.4±10.3 months) (p=0.025) (Fig. 1A), and patients with tumors with heterogeneous enhancement had poorer PFS compared to patients with tumors with homogeneous enhancement by multivariate analysis (hazard ratio : 18.432, 95% confidence interval, 1.723–198.195, p=0.016).

Based on pathologic subtypes, the mean PFS was 134.9±31.6 months for group A patients, 46.64±13.4 months for group B1 patients, and 118.7±19.2 months for group B2 patients (p=0.514) (Fig. 1B).

The mean OS was 138.5±24.6 months for group A patients and 59.7±16.8 months for group B1 patients. There was the different OS between group B1 and B2 patients without statistical significance (p=0.05) (Fig. 1C).

Eleven of 25 meningiomas had a rhabdoid or papillary component. Five of these 11 meningiomas had ≥50% rhabdoid or papillary components (Group B1). Among these, the non-rhabdoid or non-papillary component was WHO grade I in 2 patients and grade II in 2 patients. One tumor was comprised mostly of rhabdoid components. Three of these 5 patients received post-operative radiotherapy, and two patients refused adjuvant treatment. There were 2 disease-related deaths during follow-up. One patient whose tumor was mostly rhabdoid had tumor dissemination into the cerebrospinal fluid. Another patient whose tumor was mostly papillary component had local recurrence with distant metastases to the spine.

Among the 6 meningiomas with <50% rhabdoid or papillary components (Group B2), the non-rhabdoid or non-papillary tumor components were WHO grade I in 4 patients and grade II in 2 patients. Two patients with WHO grade II meningiomas underwent post-operative radiotherapy. One patient in this group experienced tumor recurrence, and the recurrent tumor was an atypical meningioma without a papillary component.

Most meningiomas are benign, and malignant meningiomas are uncommon. Because of low incidences, the clinical information of malignant meningiomas is limited even though it is generally known that they have a poor prognoses compared to benign meningiomas. Malignant meningioma commonly occurs in men and is located in the cerebral convexities11). Previously reported malignant meningioma radiologic characteristics include heterogeneous appearance, irregular cerebral surface, irregular borders (mushroom appearance), destruction of adjacent bone, and marked edema51113). However, conventional MRI is not sufficient to discriminate between benign and malignant lesions18). In this study, the MRI finding of heterogeneous enhancement was noted in 10 of 25 cases, and it was associated with early recurrence. The histopathology of malignant meningioma includes frank morphologic anaplasia, which is defined as >20 mitotic figures per 10 HPFs10). WHO classification highlights the increased malignant potential of rhabdoid and papillary meningiomas, which are WHO grade III tumors10).

Papillary meningiomas are characterized by a dominant pseudopapillary pattern, and they usually exhibit brain invasion, local or distant recurrence, and leptomeningeal dissemination71020). Rhabdoid meningiomas have a rhabdoid morphology in the background of other meningioma subtypes and usually develop early recurrence and leptomeningeal dissemination919). In the present study, one meningioma with a dominant papillary component metastasized distantly to the spine, and one meningioma with a dominant rhabdoid component disseminated into the cerebrospinal fluid. To date, there have been few studies about rhabdoid and papillary meningiomas. Some authors have stated that WHO grade III meningiomas have predominant rhabdoid or papillary components, but this is controversial17). Here, we have focused on clinical course in relation to the dominance of rhabdoid or papillary components or the pathologic findings of non-rhabdoid or non-papillary components.

Based on retrospective studies, adjuvant radiotherapy after resection of malignant meningiomas is recommended, and post-operative adjuvant radiotherapy is associated with increased OS21721). Conformal radiotherapy with dose escalation has shown a benefit for local control and survival in patients with malignant meningiomas, and it is important to identify WHO grade III tumors when making adjuvant treatment decisions312). In this study, patients were divided into three groups depending on the pathology. Group A patients had anaplastic meningiomas. Patients with meningiomas containing a predominant (≥50%) papillary or rhabdoid component were in group B1, and patients with meningiomas not containing a predominant (<50%) rhabdoid or papillary component were in group B2. We recommended radiotherapy for group A and B1 patients, and did not recommend radiotherapy for group B2. Four patients did not follow these recommendations. Two group B1 patients chose not to undergo post-operative radiotherapy because of their advanced ages, and two group B2 patients received radiotherapy for atypical meningiomas of non-rhabdoid/papillary lesion. The limitations of this study were the small number of patients and the short-term follow-up. However, we found that group A and B1 patients had similar prognoses, and group B2 patients had relatively more favorable prognoses. There were 2 recurrent tumors in group B1 patients in which the pathology of the recurrent tumors was the same as that of the original lesions. While in one recurrent group B2 tumor, the recurrent tumor was an atypical meningioma without rhabdoid/papillary components.

Meningiomas with ≥50% papillary or rhabdoid components (group B1) were more aggressive than those with <50% rhabdoid or papillary components (group B2). In group B2 patients, the pathologic findings of non-rhabdoid/papillary portion could be considered when exploring further adjuvant treatment.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, & Future Planning (2014R1A1A1004469).

References

1. Al-Habib A, Lach B, Al Khani A. Intracerebral rhabdoid and papillary meningioma with leptomeningeal spread and rapid clinical progression. Clin Neuropathol. 2005; 24:1–7. PMID: 15696777.

2. Durand A, Labrousse F, Jouvet A, Bauchet L, Kalamaridès M, Menei P, et al. WHO grade II and III meningiomas : a study of prognostic factors. J Neurooncol. 2009; 95:367–375. PMID: 19562258.

3. Hug EB, Devries A, Thornton AF, Munzenride JE, Pardo FS, Hedley-Whyte ET, et al. Management of atypical and malignant meningiomas : role of high-dose, 3D-conformal radiation therapy. J Neurooncol. 2000; 48:151–160. PMID: 11083080.

4. Karabagli P, Karabagli H, Yavas G. Aggressive rhabdoid meningioma with osseous, papillary and chordoma-like appearance. Neuropathology. 2014; 34:475–483. PMID: 24702318.

5. Kasuya H, Kubo O, Tanaka M, Amano K, Kato K, Hori T. Clinical and radiological features related to the growth potential of meningioma. Neurosurg Rev. 2006; 29:293–296. discussion 296-297. PMID: 16953450.

6. Kepes JJ, Moral LA, Wilkinson SB, Abdullah A, Llena JF. Rhabdoid transformation of tumor cells in meningiomas : a histologic indication of increased proliferative activity : report of four cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:231–238. PMID: 9500225.

7. Kim JP, Park BJ, Lim YJ. Papillary meningioma with leptomeningeal seeding. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011; 49:124–127. PMID: 21519503.

8. Kliese N, Gobrecht P, Pachow D, Andrae N, Wilisch-Neumann A, Kirches E, et al. miRNA-145 is downregulated in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas and negatively regulates motility and proliferation of meningioma cells. Oncogene. 2013; 32:4712–4720. PMID: 23108408.

9. Koenig MA, Geocadin RG, Kulesza P, Olivi A, Brem H. Rhabdoid meningioma occurring in an unrelated resection cavity with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2005; 102:371–375. PMID: 15739568.

10. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK. WHO Classification of tumours of the central nervous system. ed 3. Lyon: IARC;2007. p. 164–172.

11. Mahmood A, Caccamo DV, Tomecek FJ, Malik GM. Atypical and malignant meningiomas : a clinicopathological review. Neurosurgery. 1993; 33:955–963. PMID: 8134008.

12. Milosevic MF, Frost PJ, Laperriere NJ, Wong CS, Simpson WJ. Radiotherapy for atypical or malignant intracranial meningioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996; 34:817–822. PMID: 8598358.

13. Modha A, Gutin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas : a review. Neurosurgery. 2005; 57:538–550. discussion 538-550. PMID: 16145534.

14. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982; 5:649–655. PMID: 7165009.

15. Rogerio F, de Araújo Zanardi V, Ribeiro de Menezes Netto J, de Souza Queiroz L. Meningioma with rhabdoid, papillary and clear cell features : case report and review of association of rare meningioma variants. Clin Neuropathol. 2011; 30:291–296. PMID: 22011733.

16. Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957; 20:22–39. PMID: 13406590.

17. Sun SQ, Hawasli AH, Huang J, Chicoine MR, Kim AH. An evidence-based treatment algorithm for the management of WHO Grade II and III meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2015; 38:E3. PMID: 25727225.

18. Verheggen R, Finkenstaedt M, Bockermann V, Markakis E. Atypical and malignant meningiomas : evaluation of different radiological criteria based on CT and MRI. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1996; 65:66–69. PMID: 8738499.

19. Vinchon M, Ruchoux MM, Lejeune JP, Assaker R, Christiaens JL. Carcinomatous meningitis in a case of anaplastic meningioma. J Neurooncol. 1995; 23:239–243. PMID: 7673986.

20. Wu YT, Ho JT, Lin YJ, Lin JW. Rhabdoid papillary meningioma : a clinicopathologic case series study. Neuropathology. 2011; 31:599–605. PMID: 21382093.

21. Zhao P, Hu M, Zhao M, Ren X, Jiang Z. Prognostic factors for patients with atypical or malignant meningiomas treated at a single center. Neurosurg Rev. 2015; 38:101–107. discussion 107. PMID: 25139398.

Fig. 1

Variables predicting progression-free survival and overall survival. A : Homogenous enhancement was associated with better PFS (172.3±26.8 months) than heterogeneous enhancement (48.4±10.3 months; p=0.025). B : The mean PFS was 134.9±31.6 months for patients with group A anaplastic meningioma, 46.6±13.4 months for those who had group B1 meningiomas with ≥50% papillary or rhabdoid components (group B1), and 118.7±19.2 months for those who had group B2 meningiomas with <50% rhabdoid or papillary components (p=0.514). C : The mean OS was 138.5±24.6 months for patients with group A anaplastic meningiomas and 59.7±16.8 months for those with group B1 meningiomas having ≥50% papillary or rhabdoid components. There was the different OS (p=0.05 for group B1 ≥50% papillary or rhabdoid components compared to group B2 <50% rhabdoid or papillary components). PFS : progression-free survival, OS : overall survival.

Table 2

Pathologic and clinical analyses of meningiomas with rhabdoid or papillary components : group B1*

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download