I read with interest the recently published article by Lee et al12). The report details a case of severe postoperative cerebral oedema following a seizure in the recovery room. The procedure had otherwise been uneventful and the authors speculate that placing the epidural and subgaleal drains on active suction may have been a contributory factor. They also comment that there have only been five reported cases of unexpected massive cerebral oedema following cranioplasty. At the time of writing this may have indeed been the case, however examination of the recent cranioplasty literature reveals that this phenomenon may be more common than has previously been appreciated.

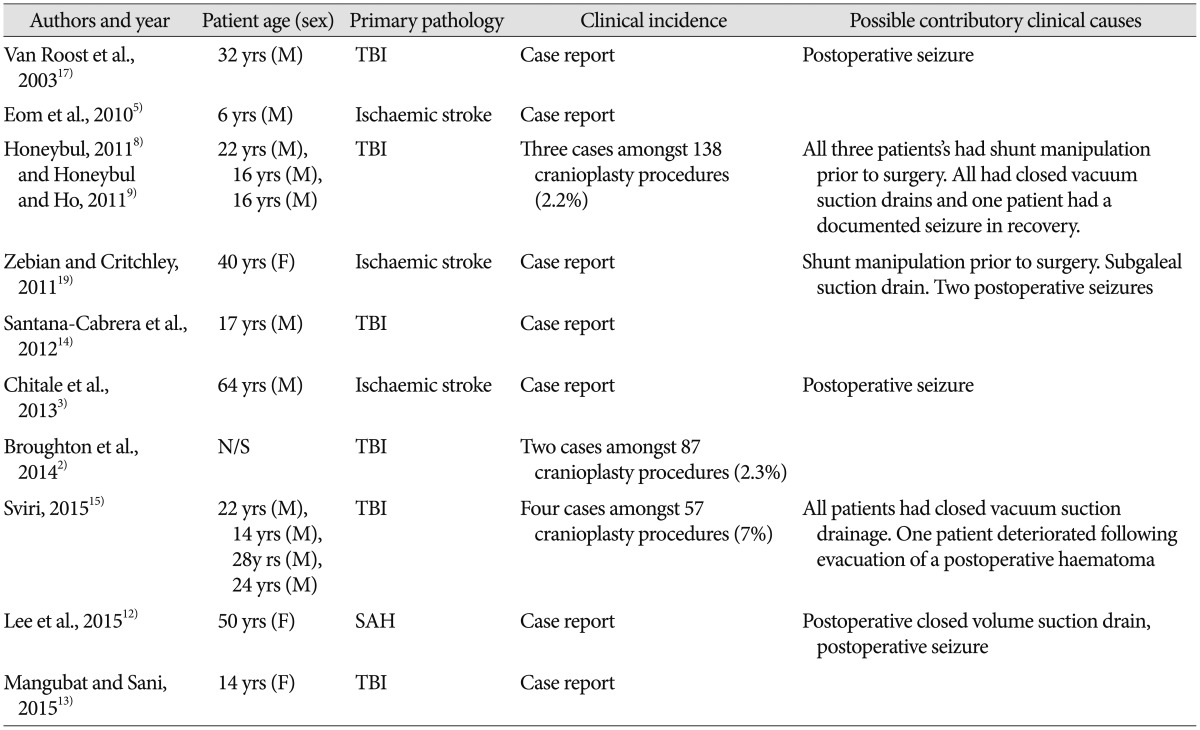

Lee et al. would not have been able to include the findings of a recent article by Sviri15) in the Journal of Neurosurgery as they had already submitted their case report. However a further literature review confirmed that there have to date been sixteen such cases (Table 1). A literature search was performed in the MEDLINE database (1966-July 2015 2012). The following keywords were used : decompressive craniectomy, cranioplasty, complications and sudden death. The bibliographies of retrieved reports were searched for additional references. For those cases that were reported as part of a cohort series this represents an incidence ranging from 2.2% to 7%, which is extraordinarily high for what is essentially a technically straightforward elective procedure28915). It may well be that these cases represent an unusual clinical occurrence that is both uncommon and unpredictable. Alternatively it may well be that this complication is just underreported. Indeed, a recent publication listed death following bone flap replacement on the outcome algorithm for patients who have had a decompressive craniectomy following ischemic stroke10). In addition, a recent article reported a mortality rate of 3.16% following cranioplasty (although in this particular study the actual cause of death was not documented18)). Notwithstanding these limitations, it would seem that death following cranioplasty is not entirely unexpected and in view of these findings care must be taken when counselling patients and their relatives prior to a cranioplasty procedure.

Currently the precise pathophysiology has yet to be determined; however, a number of authors have suggested it may relate to the use of suction drains and loss of cerebral autoregulation2816).

Cerebral pressure autoregulation is the specific intrinsic ability of the cerebrovasculature to maintain constant cerebral blood flow over a range of blood pressures1). This is generally observed between a mean arterial blood pressure of approximately 50–150 mmHg and it protects against cerebral ischaemia due to hypotension and against excessive flow (malignant hyperaemia) during hypertension, when capillary damage, oedema, diffuse haemorrhage and intracranial hypertension might otherwise result611).

Experimental studies have shown that the main autoregulatory response is located in the small vessels (diameter of <40 um) in the brain parenchyma and this involves myogenic, neurogenic and metabolic mechanisms11). These processes continuously adjust cerebrovascular resistance for changes in cerebral perfusion pressure so that the cerebral blood flow remains relatively constant. It has been demonstrated that autoregulation can be impaired over a variable time course following traumatic brain injury and this will reduce the ability of the brain to adequately control blood flow in the presence of hypo or hypertensive episodes416).

Whilst there is limited data on long term time course of autoregulation recovery, it would appear to remain impaired in a small number of severely injured patients715). Based on these studies it could be postulated that certain patients who survive serious cerebral insult such as traumatic brain injury, ischaemic stroke or subarachnoid haemorrhage may do so not only with poor neurological function but also with residual impairment in cerebral autoregulation. In circumstances where there is an acute rise in blood pressure such as during a seizure, the normal compensatory vasoconstriction may be either absent or impaired. Whilst this has not been demonstrated preoperatively, it would be difficult to attribute the massive and uncontrolled cerebral swelling to any other mechanism.

Notwithstanding the pathophysiology regarding the uncontrolled cerebral swelling, the question remains as to how clinical management of these patients may be changed in order to prevent this complication. Sviri15) noted that waiting for the patient to be fully awake prior to application of the suction drain has led no further episodes of this complication. Certainly at our institutions we have had no further episodes of sudden death following cranioplasty since I initially reported our experience in 20118). We pay close attention to seizure prophylaxis and cardiovascular stability in the immediate postoperative period. We still use suction drains; however, we do not place them on high suction in order to prevent significant pressure differentials.

In conclusion, if use of decompressive craniectomy in the management of neurological emergencies continues, close attention and wider reporting of this type of complication is required not only to focus attention on possible management strategies, but also to determine which patients are at most risk of this devastating complication.

References

1. Aaslid R, Lindegaard KF, Sorteberg W, Nornes H. Cerebral autoregulation dynamics in humans. Stroke. 1989; 20:45–52. PMID: 2492126.

2. Broughton E, Pobereskin L, Whitfield PC. Seven years of cranioplasty in a regional neurosurgical centre. Br J Neurosurg. 2014; 28:34–39. PMID: 23875882.

3. Chitale R, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez F, Dumont AS, Rosenwasser RH, Jabbour P. Infratentorial and supratentorial strokes after a cranioplasty. Neurologist. 2013; 19:17–21. PMID: 23269102.

4. Czosnyka M, Guazzo E, Whitehouse M, Smielewski P, Czosnyka Z, Kirkpatrick P, et al. Significance of intracranial pressure waveform analysis after head injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1996; 138:531–541. discussion 541-542PMID: 8800328.

5. Eom KS, Kim DW, Kang SD. Bilateral diffuse intracerebral hemorrhagic infarction after cranioplasty with autologous bone graft. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010; 112:336–340. PMID: 19896762.

6. Harper AM. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow : influence of the arterial blood pressure on the blood flow through the cerebral cortex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1966; 29:398–403. PMID: 5926462.

7. Hlatky R, Furuya Y, Valadka AB, Gonzalez J, Chacko A, Mizutani Y, et al. Dynamic autoregulatory response after severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 2002; 97:1054–1061. PMID: 12450026.

8. Honeybul S. Sudden death following cranioplasty : a complication of decompressive craniectomy for head injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2011; 25:343–345. PMID: 21501058.

9. Honeybul S, Ho KM. Long-term complications of decompressive craniectomy for head injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011; 28:929–935. PMID: 21091342.

10. Kelly AG, Holloway RG. Health state preferences and decision-making after malignant middle cerebral artery infarctions. Neurology. 2010; 75:682–687. PMID: 20631343.

11. Kontos HA, Wei EP, Navari RM, Levasseur JE, Rosenblum WI, Patterson JL Jr. Responses of cerebral arteries and arterioles to acute hypotension and hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1978; 234:H371–H383. PMID: 645875.

12. Lee GS, Park SQ, Kim R, Cho SJ. Unexpected severe cerebral edema after cranioplasty : case report and literature review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015; 58:76–78. PMID: 26279818.

13. Mangubat E, Sani S. Acute global ischemic stroke after cranioplasty : case report and review of the literature. Neurologist. 2015; 19:135–139. PMID: 25970836.

14. Santana-Cabrera L, Pérez-Ortiz C, Rodríguez-Escot C, Sánchez-Palacios M. Massive postoperative cerebral swelling following cranioplasty. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2012; 2:107–108. PMID: 22837899.

15. Sviri GE. Massive cerebral swelling immediately after cranioplasty, a fatal and unpredictable complication : report of 4 cases. J Neurosurg. 2015; 123:1188–1193. PMID: 26090828.

16. Sviri GE, Aaslid R, Douville CM, Moore A, Newell DW. Time course for autoregulation recovery following severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2009; 111:695–700. PMID: 19392589.

17. Van Roost D, Thees C, Brenke C, Oppel F, Winkler PA, Schramm J. Pseudohypoxic brain swelling : a newly defined complication after uneventful brain surgery, probably related to suction drainage. Neurosurgery. 2003; 53:1315–1326. discussion 1326-1327PMID: 14633298.

18. Zanaty M, Chalouhi N, Starke RM, Clark SW, Bovenzi CD, Saigh M, et al. Complications following cranioplasty : incidence and predictors in 348 cases. J Neurosurg. 2015; 123:182–188. PMID: 25768830.

19. Zebian B, Critchley G. Sudden death following cranioplasty : a complication of decompressive craniectomy for head injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2011; 25:785–786. PMID: 22115018.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download