Abstract

Objective

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) acts as a chaperone on the cell surface, and it has been reported that PDI is associated with the tumor cell migration and invasion. The aims of this study are to investigate the anti-migration effect of bacitracin, which is an inhibitor of PDI, and the associated factor in this process.

Methods

U87-MG glioma cells were treated with bacitracin in 1.25, 2.5, 3.75, and 5.0 mM concentrations. Western blot with caspase-3 was applied to evaluate the cytotoxicity of bacitracin. Adhesion, morphology, migration assays, and organotypic brain-slice culture were performed to evaluate the effect of bacitracin to the tumor cell. Western blot, PCR, and gelatin zymography were performed to investigate the associated factors. Thirty glioma tissues were collected following immunohistochemistry and Western blot.

Results

Bacitracin showed a cytotoxicity in 3rd (p<0.05) and 4th (p<0.001) days, in 5.0 Mm concentration. The cell adhesion significantly decreased and the cells became a round shape after treated with bacitracin. The migration ability, the expression of phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (p-FAK) and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) decreased in a bacitracin dose- and time-dependent manner. The U87-MG cells exhibited low-invasiveness in the 2.5 mM, compared with the untreated in organotypic brain-slice culture. PDI was expressed in the tumor margin, and significantly increased with histological glioma grades (p<0.001).

Glioblastoma is the most aggressive malignant primary brain tumor. Although conventional medical treatments for glioma are reasonably effective in controlling the disease, all of them have limitations1034). Exceptional invasiveness is a characteristic feature of glioma and it is one of the major reasons for these treatments failure.

There are many molecules involved in the motility of glioma cells, one of them is integrin. It has been demonstrated that integrin is related with resistance of glioma cells to temozolomide10) and play a role in glioma cell invasion and migration2331). Moreover, the molecule termed protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), which is an enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), catalyzes a reduction of mispaired thiol residues of a particular substrate, and act as an isomerase8). Recently, several studies have shown that PDI is secreted by the cells and exists on the cell surface6192729), PDI mediates the conformation of integrin involved in binding with ECM51921). We set up a hypothesis that inhibition of PDI to reduce the affinity of integrin binding with ECM would finally inhibit glioma tumor cell motility.

Bacitracin, which is an inhibitor of PDI, is a mixture of related cyclic polypeptides produced by organisms of the licheniformis group of Bacillus subtilis var Tracy. Bacitracin has low cell membrane permeability, therefore it acts as an inhibitor via binding with reduced PDI on the cell surface42433). The inhibitory effect of bacitracin is higher than that of other anti-PDI and integrin antibodies7). It has been demonstrated that after using bacitracin as an inhibitor of PDI, chemotherapy agents-induced apoptosis increased in melanoma cells22), and resistant glioma cells became sensitive to temozolomide28).

In the present study, we investigated four human glioma cell lines using Western bolts, migration, and invasion assay to identify the association between PDI and cell motility. Then we choose the high motile cell line (U87-MG) to investigate the inhibit effect of bacitracin. We detected the expression of caspase 3 to identify the safety concentration and time of the bacitracin treatment. And we using the adhesion and morphology assay to evaluate the effect of bacitracin to the integrin. Using the migration assay and organotypic brain-slice culture to evaluate the anti-migration and -invasion effect of bacitracin to the human glioma cell line. Additionally, we detected the phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (p-FAK) and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2) expression by using Western bolts, RT-PCR, and gelatin zymography to indicate the possible mechanism in the bacitracin treatment. Immunohistochemical study and Western blots were employed to evaluate the expression of PDI in human glioma samples.

Thirty specimens, including WHO grade II, III, and IV glioma, were obtained from patients who underwent surgery at our hospital between 2006 and 2013. All of these tissues were obtained after informed consent of the patients, and the study was approved by our hospital Institutional Review Board (CNUHH-2015-002). Human malignant glioma cell lines U87-MG, U118, U251, and U343MG-A (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) were routinely maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin.

U87-MG cells (1×104) were seeded in an 8-well chamber slide (LAB-TEK, Brendale, Australia). After 24 hours, the cells were fixed using 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and then the cells were blocked with 1% bovine albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS-T (involving 1% tween-20 in PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Then, 1 : 50 diluted Anti-PDI antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) was added, and the sample was incubated overnight at 4℃. The secondary antibody used was the Alexa Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at a concentration of 1 : 200. Finally, we mounted the slide with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Cells (3–4×104 of U87-MG, U251, U118, and U343MG-A) were suspended in 0.7 mL medium without serum and seeded in µ-dish (35 mm high culture-insert ibiTreat; Ibidi) per well in monolayer culturere and were incubated overnight. The culture-insert and the medium were removed. Then, 3 mL of medium without serum and medium with different concentrations of bacitracin and without serum were added. Cell migration distance was measured by microscopy every 2 hours.

Proteins (30 mg) from human glioma samples and U87-MG cells treated and untreated with bacitracin were size separated by electrophoresis in a discontinuous system consisting of 8%, 10%, and 12% polyacrylamide resolving gels and 5% polyacrylamide stacking gels and transferred to a PVDF membrane. After blocking for 1 hour in PBS supplemented with 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated with 1 : 1000 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-pFAK (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), 1 : 1000 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-MMP2 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and 1 : 10000 dilution of mouse monoclonal anti-actin Ab-5 (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA, USA) overnight, and images were obtained with the LAS-4000 image analyzer (Fuji, Tokyo, Japan). A 1 : 1000 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) was used as a cell apoptosis marker.

Cell-surface PDI was estimated by labeling with either sulfosuccinimidobiotin (SSB, Pierce Technology, Rockford, IL, USA)11), or 3-(N-maleimidylpropionyl) biocytin (MPB, Molecular Probes, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)11). Both SSB and MPB are membrane impermeable. SSB labels the primary amines in PDI, and MPB labels the reactive site sulfhydryls. After 4 days, both untreated and treated U87-MG cells (4×106) were washed twice, resuspended in 1 mL PBS containing 100 mM of SSB or MPB, and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The remaining SSB was quenched with 200 mM glycine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 min at room temperature. The remaining MPB was quenched with 200 mM glutathione (GSH; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 min at room temperature, and excess GSH was quenched with 400 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with 1 mL PBS, counted, and 3×106 labeled cells were sonicated in RIPA buffer. The cells were then incubated with 100 mL 50% streptavidin-agarose slurry (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 60 min at 4℃ on a rotary mixer. Bound proteins were washed five times with washing buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8, buffer containing 0.15 M NaCl and 0.05% TritonX-100), and SSB- or MPB-labeled PDI was detected by Western blot with a 1 : 1000 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-PDI (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).

Total RNA was isolated from U87-MG cells, using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Gaithersbury, MD, USA). A total of 1 µg of RNA was reverse transcribed to synthesize the cDNA. For the first strand synthesis, 1 µg of the purified total RNA was incubated with oligo (dT) (0.5 µg/µL, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) for 5 minutes at 70℃, followed by the addition of buffer containing 4 µL of 5 × Reaction buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 1 µL of dNTP (10 mM each), 3.5 µL of 25 mM MgCl2, 2 µL of RNase Inhibitor (40 U/µL, Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and 1 µL of reverse transcriptase (200 U/µL, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The reaction volume was 20 µL, and the reaction was carried out for 90 minutes at 42℃, and then for 2 minutes at 90℃. Reactions with varying numbers of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycles were run for each transcript. The primers used were 5'-CTGATGGCACCCATTTACACCT-3' and 5'-GATCTGAGCGATGCCATCAAA-3' for MMP-2, and 5'-GTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAAC-3' and 5'-GTTGAGGTCAATGAAGGG-3' for GAPDH, which was used as an internal control.

The U87-MG cells were treated with different concentrations of bacitracin for 1 and 2 days, then media were changed to serum-free DMEM for 1 day. Cultured media were centrifuged, the pellet was discarded, and 10 µg of total protein from the media was electrophoresed on 10% polyacrylamide gels containing 10 mg/mL of gelatin (type A, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The gel was washed three times, and it was then incubated for 18 hours at 37℃ in incubation buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM CaCl2, 200 mM NaCl]. The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (0.2% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, 20% Methanol, 10% Acetic acid in H2O) for 2 days, and then it was destained with buffer (20% Methanol, 10% Acetic acid in H2O).

The U87-MG cells were centrifuged and the pellets were suspend in 3 mL media without serum. The cells were then counted and incubated for 1 hour on ice with different concentration of bacitracin media without serum. The control group was incubated in media without serum. After 1 hour, the cells were counted and equal number of control and treated cells (5×103) were seeded in 96-well cell culture plate. To measure the number of adherent cells after 2 and 24 hours, 0.5 mg/mL MTT solution was added per well, and were incubated for an additional 4 hours. Then, the supernatants from each wells were removed and 0.1 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added per well. The absorbance of samples was read at 562 nm and 620 nm wave lengths.

5×103 U87-MG cells were seeded in 96-well cell culture plate. After 24 hours, the media were changed with the media containing different concentrations of bacitracin, and the control group was always exposed to the normal media. On the fifth day, all of the media were changed to normal media. The experiment was stopped on the seventh day. The cell morphology was assessed every day.

The human glioma tissues were pretreated with heat-induced epitope retrieval and were carried out for 10 minutes in a pressure cooker at 120℃ in target retrieval solution, PH 9 (Dako, Carpentaria, CA, USA). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating samples in PBS containing 3% H2O2, and the non-specific binding sites were blocked by treatment with 3% bovine albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. Anti-PDI (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) was added and incubated for overnight at 4℃, after that the secondary antibody (Dako, Carpentaria, CA, USA) was added, and the samples were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. The tissue sections were ready for the chromogen reaction with DAB (Dako, Carpentaria, CA, USA) for 45 second at room temperature. Counterstaining was performed using Harris hematoxylin (ScyTek, Logan, UT, USA).

The brain tissue was obtained from 5 weeks old Sprague-Dawley rat, and was cut into 1 mm thick with a brain-slice apparatus. The brain-slices were placed onto the upper chamber with a pore size 0.4 µm transwell culture dish (Coring Costar, Corning, NY, USA), then U87-MG cells, which were stained with DiI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for overnight, implanted in the central hole of the brain-slice incubated for 10 days. After that, the brain-slices were fixed with 4% PFA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4℃ overnight and placed on a microscopic slide designed for 1 mm thick brain slice and filled with mounting medium (Dako, Carpentaria, CA, USA)1415).

Quantitative data which were obtained from the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in cells, the invasion assay and the migration assay were compared with one-way ANOVA. The absorbance from the adhesion assay using five groups of cells was compared with repeated measures ANOVA. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

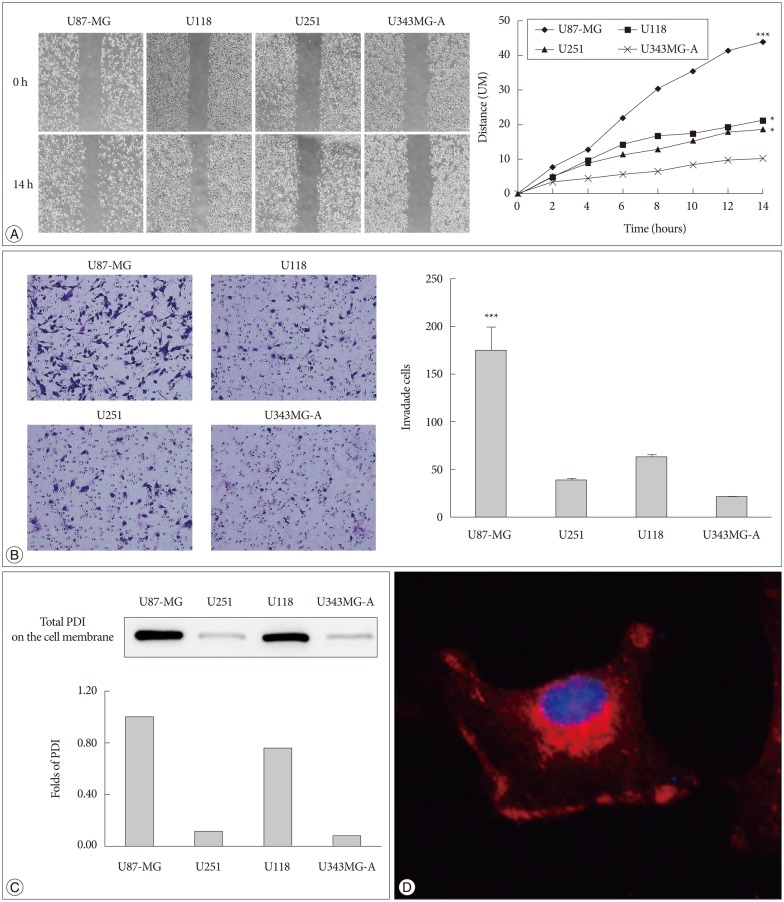

It was found that U87-MG cell line has the highest motility among the four glioma cell lines (Fig. 1A, B). We also determined the protein level of PDI on the cell surface in four glioma cell lines. U87-MG cells had the highest expression of PDI compared with the others cell lines (Fig. 1C). Meanwhile, to determine the existence of PDI on the cell surface, we performed the immunofluorescence. It was found that PDI is expressed in the cytosol and on the cell surface (Fig. 1D).

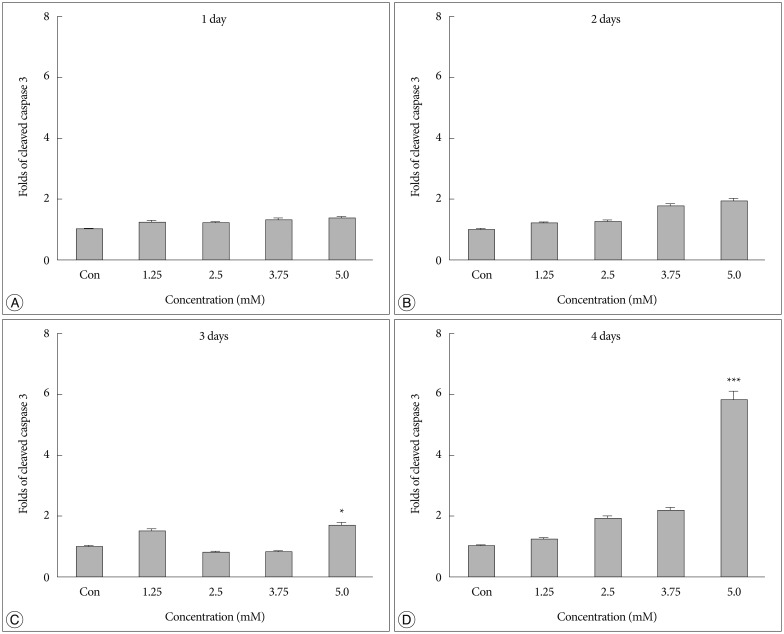

No difference in the density of cleaved caspase 3 was detected between cells treated with bacitracin and control cells after 1 or 2 days (Fig. 2A, B). However, a significant cell death (p<0.05) (Fig. 2C) was detected after 3 days between 5.0 mM bacitracin-treated cells and the control. A similar result was found after 4 days (p<0.001) (Fig. 2D). Therefore, the 5 mM bacitracin concentration was not used in any other experiments, which using bacitracin over 2 days.

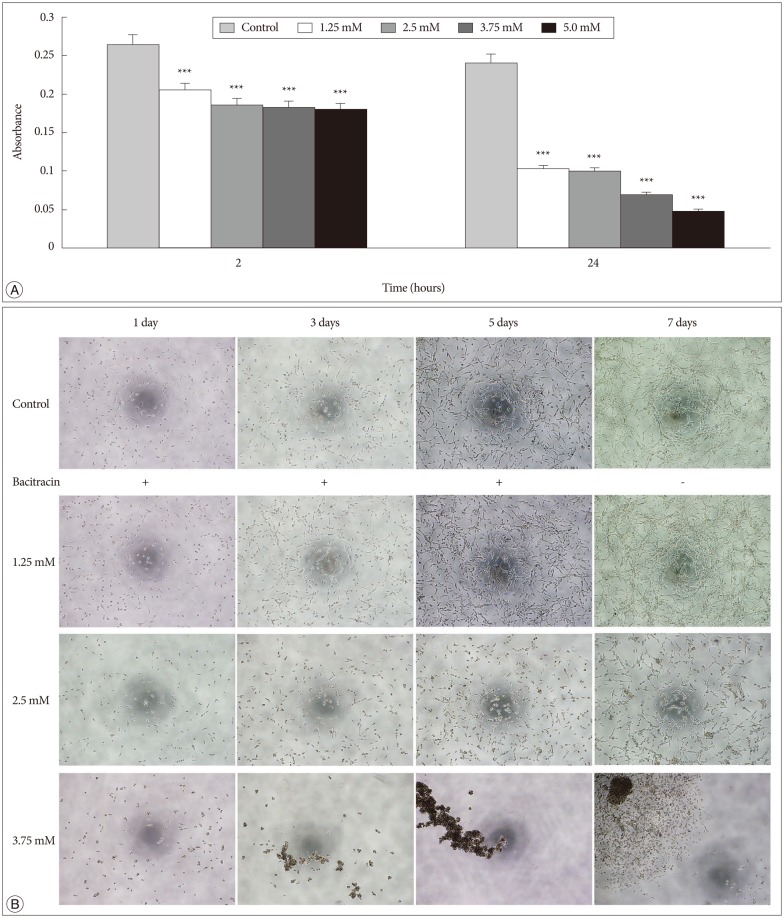

In the adhesion assay, the cells untreated or treated with bacitracin in different concentration showed significant difference between each groups either at 2 hours, or at 24 hours, and in treated groups the adhesion ability decreased in a dose-dependent manner (p<0.001) (Fig. 3A).

In the morphology assay, it was found that the cell morphology and growth pattern were altered in the 2.5 and 3.75 mM bacitracin groups, the cells became a round shape and they aggregated with each other, compared to the control group. After changing the media 2 days later, the cell morphology and growth pattern were restored (Fig. 3B).

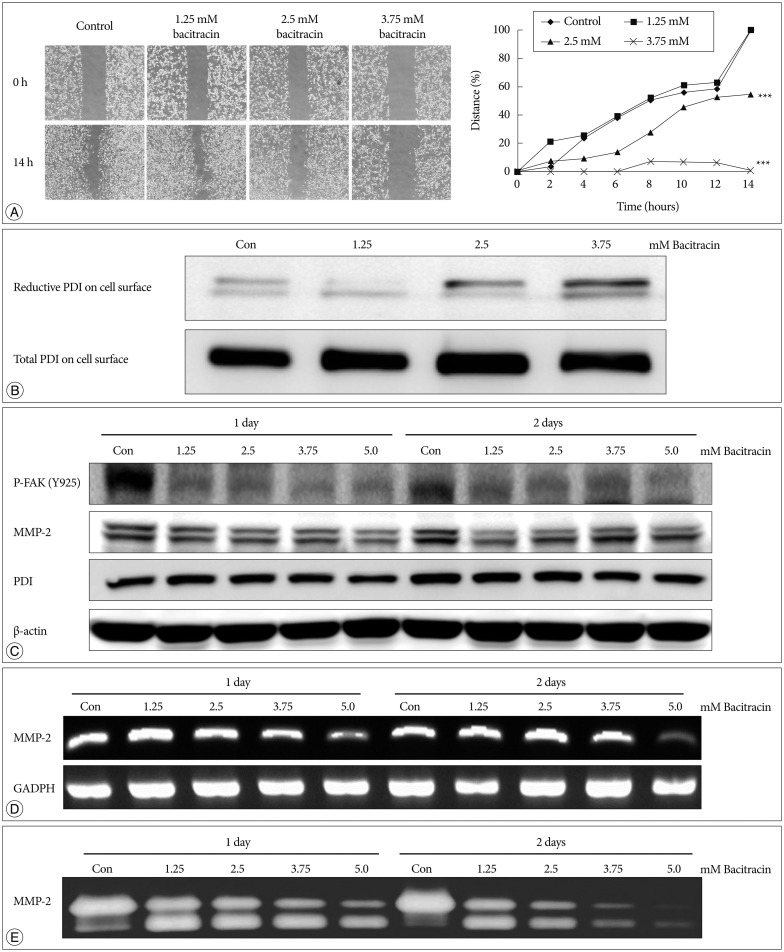

After 14 hours, in the control group and 1.25 mM bacitracin group, there is no significant difference between each other, however, the 2.5 and 3.75 mM bacitracin groups have significant difference, compare with control group, cell migration decreased in a dose-dependent manner (p<0.001) (Fig. 4A).

Total and reduced PDI were labeled on cell membranes after treating the cells with bacitracin and subjecting them to Westem blot. Total PDI expressed on the cell membrane remained unchanged, whereas expression of reduced PDI increased with the increase in bacitracin dose (Fig. 4B).

It was found that the expression of total PDI in cells did not change after using bacitracin, nevertheless, p-FAK and MMP-2 expressions were decreased in the bacitracin-treated groups (Fig. 4C). In RT-PCR, the expression of MMP-2 was decreased in the high dose of bacitracin (Fig. 4D). A similar result was also obtained in the gelatin zymography; the expression of MMP-2 in the supernatant was decreased with an increase in the concentration of bacitracin (Fig. 4E).

In the control group, the U87-MG cells exhibited much high invasiveness, and the distance from central to the margin was longer than that in the treatment group. Cells treated with bacitracin migrated a short distance, aggregated, and exhibited less invasiveness compared with those of the control (Fig. 5A, 5B).

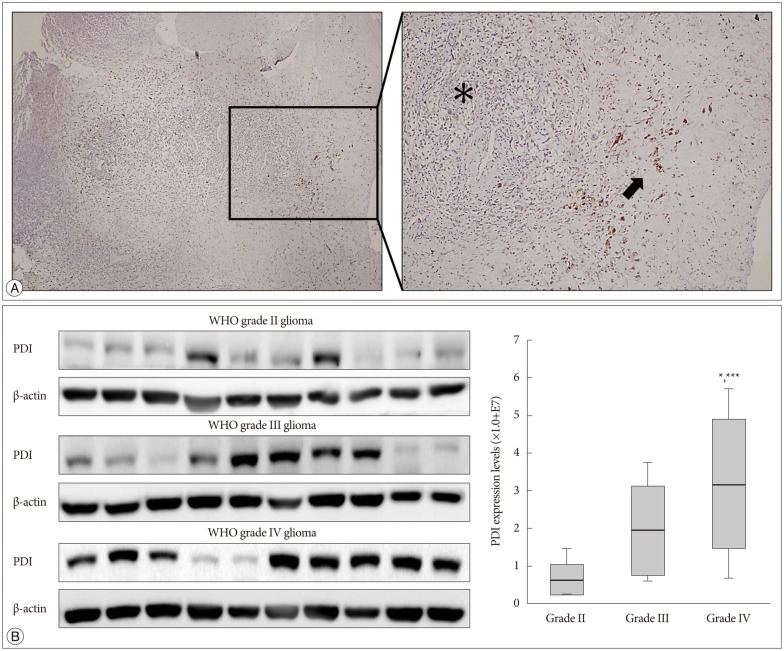

The immunohistochemistry of glioblastoma specimens showed that PDI expression in the tumor margin was higher than that in the tumor core (Fig. 6A).

WHO glioma grading is classified according to the degree of tumor cell differentiation, and the invasiveness of high grade gliomas (WHO III and IV) is higher than that of low grade gliomas (WHO I and II). It is showed that grade IV had the highest PDI expression compared with that of the other two grades (Fig. 6B).

To dates, several molecules have been demonstrated to be involved in glioma cell motility. First of all, we focused on integrin, which mediates the outside-in signaling through binding with the ECM and play a key role in cellular shape, motility, adhesion, and cell cycle1820). Several subtypes of integrin have been reported to be involved in glioma cell motility and treatment1023). In addition, integrin α2β1, α5β1, α6β1, α9β1, and αvβ3 are strongly expressed in glioblastoma samples compare with normal brain tissue, and the expression of integrin αvβ3 and αvβ5 positively correlates with histological tumor grade31). At the same time, a conformational change occurs when integrin bind with the ECM, which exposes integrin to ECM binding sites with high affinity for ligands. This conformational change in integrin, which is the thiol-disulfide exchange reaction in the integrin β subunit, plays a key role in integrin activation. The main protein that regulates thiol-disulfide exchange reaction in integrin is PDI51921). In recent years, it has been postulated that PDI on the cell surface, acts as a reductase, that cleaves the disulfide bonds of proteins attached to the cell surface, and inside the cell, it forms disulfide bonds1). Investigators have reported that PDI interacts with the integrin which have β1 and β3 subunits7). As mentioned above, the main integrin expressed in glioma have subunits that interact with PDI. Moreover, PDI is related to tumorigenesis, and its result is associated with the endoplasmic reticular stress response (ERSR) and the unfolded protein response (UPR)32228). We also found that the expression of PDI in the glioma is higher than in normal brain tissues (data not shown). Additionally, PDI is highly expressed in U87-MG cell line, which has high mobility, compared with other glioma cell lines. It is reported previously that PDI has a relationship with tumor angiogenesis3036). We became more convinced that PDI associated with tumor cell migration and invasion. It is also reported that inhibition of PDI decreased the resistance of glioma cells to temozolomide28). Besides, PDI has been indicated as a new target in cancer therapy35). We set up a hypothesis that inhibiting the function of PDI in mediating integrin might decrease the cell motility.

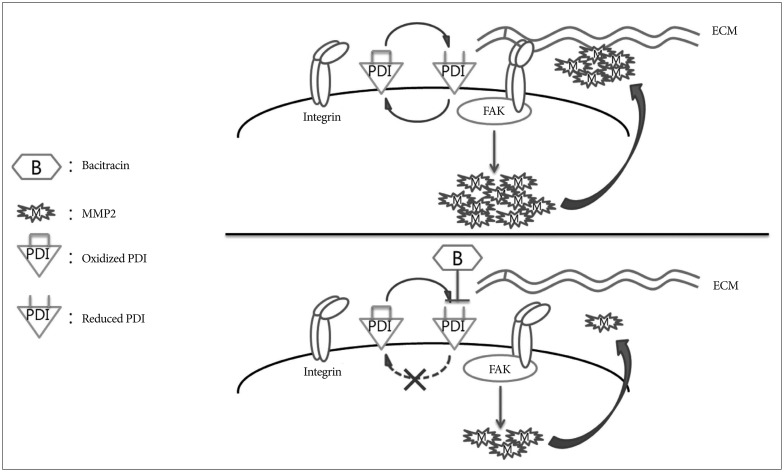

We chose bacitracin, which is well known inhibitor of PDI, as the candidate of malignant glioma treatment. It is reported that bacitracin induced glioma xenograft cells death at 10 mM concentration7). We suspected the reasons of bacitracin induced apoptosis like these : bacitracin interferes the function of integrin, resulting integrin-induced cell apoptosis; and small amount of bacitracin through the cell membrane inhibits PDI in the cell, resulting ERSR-induced cell apoptosis. The caspase-3 associate with cell apoptosis and is participate in all of these pathways2121337). Therefore, we used caspase-3 as a cell apoptosis marker to investigate the cytotoxicity of bacitracin. We found that the high dose of bacitracin (5.0 mM) induced U87-MG cells apoptosis, over 2 days treatment. It has low cell membrane permeability and it mostly affects the superficial PDI via binding with cysteines in reduced PDI424). Our study demonstrated that reduced PDI increased in a bacitracin dose-dependent manner, while there was no change in total PDI on the cell surface. Moreover, bacitracin increased the chemotherapeutic agent-induced apoptosis in tumors2228). Bacitracin also inhibited the invasion and migration of glioma xenograft cells in vitro7). Our data also demonstrate the inhibitory effect of bacitracin in U87-MG cell line in a dose-dependent manner. Meanwhile, the adhesion and morphology assays showed that bacitracin interferences the integrin function. Additionally, we investigated two molecules, which are downstream of integrin and are involved in tumor invasion and migration. FAK, which is linked to the outside-in signaling pathway of integrin, and afterwards it is phosphorylated by itself or other molecule21). It is known that FAK phosphorylation is related to glioma growth926). Six phosphorylation sites in FAK have been identified, and the one that we are interested in is Y925, which is involved in the production of MMP-2, the second molecule that we investigated. MMP-2 is a well known collagen proteinase and it plays a critical role in tumor invasion and migration, as well as in glioma1725). To investigate the effect of bacitracin on p-FAK and MMP-2 expression, we performed Western blot, RT-ePCR and gelatin zymography. Our data showed that the p-FAK (Y925) and MMP-2 expression were decreased in the cells, as well as the MMP-2 secreted in media, with an increase in bacitracin doses and treatment times. In organotypic brain-slice culture, an ex vivo study, the U87-MG cells treated with 2.5 mM bacitracin the most safe and effective concentration, became less invasiveness compare with untreated. On the basis of our knowledge and our findings, we conjecture that these molecules were altered under different conditions, irrespective of the presence of bacitracin (Fig. 7).

There is still controversy about whether bacitracin is a specific inhibitor of PDI16). However, the inhibitory effect of bacitracin is higher than that of PDI and integrin antibodies in the functional assay7). It needs to be acknowledged that the potential role of bacitracin in glioma therapy has certain limitations, results of bacitracin caused nephrotoxicity in rats32) and maybe caused apoptosis of normal cells. In this study, however, we used the highest motile cell line among in the four human glioma cell lines, the effect of bacitracin in other cell lines need to investigate. And we just studied the effect of bacitracin in vitro and ex vivo, we are going to research the effect in animal study.

Our study shows the role of bacitracin in glioma cells; it not only inhibits PDI, but it also indirectly interferences the integrin outside-in signaling pathway. Bacitracin has the potential to be used as an anti-invasive agent combine with conventional medical treatments for glioma therapy; but before that, bacitracin need to be improved, and the most important point is selection of an appropriate concentration of bacitracin. Further studies are required to assess the anti-invasive effect of bacitracin in animal tumor model system.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant (CRI 12032-1) from the Chonnam National University Hospital Research Institute of Clinical Medicine. The biospecimens and data used for this study were provided by the Biobank of Chonnam National University Hwasun Hwasun Hospital, a member of the Korea Biobank Network.

References

1. Benham AM. The protein disulfide isomerase family : key players in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012; 16:781–789. PMID: 22142258.

2. Deep G, Kumar R, Jain AK, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits fibronectin induced motility, invasiveness and survival in human prostate carcinoma PC3 cells via targeting integrin signaling. Mutat Res. 2014; 768:35–46. PMID: 25285031.

3. Di Santo N, Ehrisman J. Research perspective : potential role of nitazoxanide in ovarian cancer treatment. Old drug, new purpose? Cancers (Basel). 2013; 5:1163–1176. PMID: 24202339.

4. Dickerhof N, Kleffmann T, Jack R, McCormick S. Bacitracin inhibits the reductive activity of protein disulfide isomerase by disulfide bond formation with free cysteines in the substrate-binding domain. FEBS J. 2011; 278:2034–2043. PMID: 21481187.

5. Essex DW. The role of thiols and disulfides in platelet function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004; 6:736–746. PMID: 15242555.

6. Essex DW, Chen K, Swiatkowska M. Localization of protein disulfide isomerase to the external surface of the platelet plasma membrane. Blood. 1995; 86:2168–2173. PMID: 7662965.

7. Goplen D, Wang J, Enger PØ, Tysnes BB, Terzis AJ, Laerum OD, et al. Protein disulfide isomerase expression is related to the invasive properties of malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006; 66:9895–9902. PMID: 17047051.

8. Hatahet F, Ruddock LW. Substrate recognition by the protein disulfide isomerases. FEBS J. 2007; 274:5223–5234. PMID: 17892489.

9. Huang G, Ho B, Conroy J, Liu S, Qiang H, Golubovskaya V. The microarray gene profiling analysis of glioblastoma cancer cells reveals genes affected by FAK inhibitor Y15 and combination of Y15 and temozolomide. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014; 14:9–17. PMID: 23387973.

10. Janouskova H, Maglott A, Leger DY, Bossert C, Noulet F, Guerin E, et al. Integrin α5β1 plays a critical role in resistance to temozolomide by interfering with the p53 pathway in high-grade glioma. Cancer Res. 2012; 72:3463–3470. PMID: 22593187.

11. Jiang XM, Fitzgerald M, Grant CM, Hogg PJ. Redox control of exofacial protein thiols/disulfides by protein disulfide isomerase. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274:2416–2423. PMID: 9891011.

12. Johnson GG, White MC, Grimaldi M. Stressed to death : targeting endoplasmic reticulum stress response induced apoptosis in gliomas. Curr Pharm Des. 2011; 17:284–292. PMID: 21348829.

13. Johnson GG, White MC, Wu JH, Vallejo M, Grimaldi M. The deadly connection between endoplasmic reticulum, Ca2+, protein synthesis, and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in malignant glioma cells. Neuro Oncol. 2014; 16:1086–1099. PMID: 24569545.

14. Jung S, Kim HW, Lee JH, Kang SS, Rhu HH, Jeong YI, et al. Brain tumor invasion model system using organotypic brain-slice culture as an alternative to in vivo model. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002; 128:469–476. PMID: 12242510.

15. Jung TY, Jung S, Ryu HH, Jeong YI, Jin YH, Jin SG, et al. Role of galectin-1 in migration and invasion of human glioblastoma multiforme cell lines. J Neurosurg. 2008; 109:273–284. PMID: 18671640.

16. Karala AR, Ruddock LW. Bacitracin is not a specific inhibitor of protein disulfide isomerase. FEBS J. 2010; 277:2454–2462. PMID: 20477872.

17. Kim CS, Jung S, Jung TY, Jang WY, Sun HS, Ryu HH. Characterization of invading glioma cells using molecular analysis of leading-edge tissue. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011; 50:157–165. PMID: 22102942.

18. Lahav J, Gofer-Dadosh N, Luboshitz J, Hess O, Shaklai M. Protein disulfide isomerase mediates integrin-dependent adhesion. FEBS Lett. 2000; 475:89–92. PMID: 10858494.

19. Lahav J, Wijnen EM, Hess O, Hamaia SW, Griffiths D, Makris M, et al. Enzymatically catalyzed disulfide exchange is required for platelet adhesion to collagen via integrin alpha2beta1. Blood. 2003; 102:2085–2092. PMID: 12791669.

20. Li X, Ishihara S, Yasuda M, Nishioka T, Mizutani T, Ishikawa M, et al. Lung cancer cells that survive ionizing radiation show increased integrin α2β1- and EGFR-dependent invasiveness. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e70905. PMID: 23951036.

21. Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH. Integrin activation takes shape. J Cell Biol. 2002; 158:833–839. PMID: 12213832.

22. Lovat PE, Corazzari M, Armstrong JL, Martin S, Pagliarini V, Hill D, et al. Increasing melanoma cell death using inhibitors of protein disulfide isomerases to abrogate survival responses to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Res. 2008; 68:5363–5369. PMID: 18593938.

23. Ma J, Cui W, He SM, Duan YH, Heng LJ, Wang L, et al. Human U87 astrocytoma cell invasion induced by interaction of βig-h3 with integrin α5β1 involves calpain-2. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e37297. PMID: 22629380.

24. Mandel R, Ryser HJ, Ghani F, Wu M, Peak D. Inhibition of a reductive function of the plasma membrane by bacitracin and antibodies against protein disulfide-isomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993; 90:4112–4116. PMID: 8387210.

25. Ryu HH, Jung S, Jung TY, Moon KS, Kim IY, Jeong YI, et al. Role of metallothionein 1E in the migration and invasion of human glioma cell lines. Int J Oncol. 2012; 41:1305–1313. PMID: 22843066.

26. Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, Keir ST, Song L, Wickman S, Jackson D, et al. A novel low-molecular weight inhibitor of focal adhesion kinase, TAE226, inhibits glioma growth. Mol Carcinog. 2007; 46:488–496. PMID: 17219439.

27. Shin BK, Wang H, Yim AM, Le Naour F, Brichory F, Jang JH, et al. Global profiling of the cell surface proteome of cancer cells uncovers an abundance of proteins with chaperone function. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278:7607–7616. PMID: 12493773.

28. Sun S, Lee D, Ho AS, Pu JK, Zhang XQ, Lee NP, et al. Inhibition of prolyl 4-hydroxylase, beta polypeptide (P4HB) attenuates temozolomide resistance in malignant glioma via the endoplasmic reticulum stress response (ERSR) pathways. Neuro Oncol. 2013; 15:562–577. PMID: 23444257.

29. Terada K, Manchikalapudi P, Noiva R, Jauregui HO, Stockert RJ, Schilsky ML. Secretion, surface localization, turnover, and steady state expression of protein disulfide isomerase in rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995; 270:20410–20416. PMID: 7657616.

30. Tian F, Zhou X, Wikström J, Karlsson H, Sjöland H, Gan LM, et al. Protein disulfide isomerase increases in myocardial endothelial cells in mice exposed to chronic hypoxia : a stimulatory role in angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009; 297:H1078–H1086. PMID: 19617410.

31. Tysnes BB, Mahesparan R. Biological mechanisms of glioma invasion and potential therapeutic targets. J Neurooncol. 2001; 53:129–147. PMID: 11716066.

32. Wang EJ, Snyder RD, Fielden MR, Smith RJ, Gu YZ. Validation of putative genomic biomarkers of nephrotoxicity in rats. Toxicology. 2008; 246:91–100. PMID: 18289764.

33. Weston BS, Wahab NA, Roberts T, Mason RM. Bacitracin inhibits fibronectin matrix assembly by mesangial cells in high glucose. Kidney Int. 2001; 60:1756–1764. PMID: 11703593.

34. Wild-Bode C, Weller M, Rimner A, Dichgans J, Wick W. Sublethal irradiation promotes migration and invasiveness of glioma cells : implications for radiotherapy of human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2001; 61:2744–2750. PMID: 11289157.

35. Xu S, Sankar S, Neamati N. Protein disulfide isomerase : a promising target for cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2014; 19:222–240. PMID: 24184531.

36. Yu SJ, Yoon JH, Yang JI, Cho EJ, Kwak MS, Jang ES, et al. Enhancement of hexokinase II inhibitor-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via augmenting ER stress and anti-angiogenesis by protein disulfide isomerase inhibition. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2012; 44:101–115. PMID: 22350012.

Fig. 1

PDI is related to tumor cell motility and it is localized in the cell cytosol and on the cell surface. A : The cell migration distance is measured with microscopy every 2 hours. The chart (right) shows the mobility of each cell lines (100×magnification). The distance between two sides is measured at five sites for the indicated periods of time. U87-MG, U118, and U251 have high motility, compare with U343MG-A. B : The same cell lines are used in the invasion assay, the invaded cells are counted after 24 hours (200×magnification). The experiment is performed 3 times, each data point represents the mean+SD of 4 cell lines, at the right. C : The expression of total PDI on the cell surface is shown by Western blots, and the fold difference between these four cell lines is displayed in the lower portion of the chart. D : PDI expression is observed in monolayer culture of U87-MG cells by immunofluorescence. Images are obtained by confocal laser scanning microscopy (400×magnification). *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. PDI : protein disulfide isomerase.

Fig. 2

A high Bacitracin concentration induces tumor cell apoptosis. A and B : No difference in caspase-3 expression was observed on days 1 and 2 after bacitracin treatment. C : A significant cell death was observed between the 5.0 mM bacitracin and controls group after 3 days. however, 1.25, 2.5, and 3.75 mM bacitracin did not induced significant more cell death. D : A similar result was detected on day 4. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

Fig. 3

Bacitracin interferences the integrin function in respect to cell adhesion and morphology. A : Adhesion assay shows that the bacitracin treated and non-treated U87-MG cells exhibit different adhesion ability at the treatment doses and times, and each data point represents the mean+SD of 5 groups. B : Morphology assay shows that the cell morphology is altered after treatment with bacitracin at the concentrations of 2.5 and 3.75 mM (100×magnification). The image with red border in the 3.75 mM group, indicate the effect of bacitracin in cell morphology is reversible. ***p<0.001.

Fig. 4

Bacitracin inhibits U87-MG cell migration through affects the expression of certain molecules. A : The images show the initial and final stages of 4 groups (400×magnification). The chart show the moving tendency of U87-MG cells under different conditions. B : Western blot with labeled PDI on the cell surface shows that there is no remarkable distinction in total PDI on the cell surface; conversely, reduced PDI is increased along with an increase of the concentration of bacitracin. At the top figure the two bands indicate the members of PDI family. C : The p-FAK and MMP-2 expression decrease in the treated U87-MG cells, compare with the control group; however, the expression of PDI shows no significant difference under the same condition. In the MMP-2 image, the upper bands and the lower bands indicate latent form and activate form, respectively. D : The expression of MMP-2 is decreased with increasing of bacitracin concentration as shown by RT-PCR. E : The gelatin zymography shows that the expression of secreted MMP-2 decreases in a dose-dependent manner. The upper and lower bands also indicate the latent form and activate form, respectively. PDI : protein disulfide isomerase, p-FAK : phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase, MMP-2 : matrix metalloproteinase-2.

Fig. 5

Bacitracin inhibits U87-MG cell invasion in brain-slice. A : The cells radiate out in all direction and exhibit a high invasiveness. B : The cells cultured in the media contained 2.5 mM bacitracin, aggregate in the hole of the brain-slice. Although the cells show a high density, they always exhibit a low invasiveness, compare with control group. All the images are obtained by confocal laser scanning microscopy (100×magnification).

Fig. 6

The expression of PDI in human tissue samples. A : Immunohistochemistry of a glioblastoma sample obtained from a patient show the PDI location in comparison between the tumor core and the tumor margin. Left : Low magnification human glioblastoma immunohistochemistry. Right : High magnification immunohistochemistry; black asterisk indicate the tumor core and low PDI expression; black arrows indicate tumor margin and high PDI expression. B : The expression of PDI shows by the Western blot, in WHO grade II, grade III and grade IV gliomas. The PDI expression in grade IV glioma showed a significant difference compare with that in gliomas of the other two grades *p<0.05, ***p<0.001. PDI : protein disulfide isomerase.

Fig. 7

Schematic model showing the potential role of bacitracin in inhibiting glioma cell invasion. Oxidized protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and reduced PDI interconvert under the bacitracin-free condition. During the transformation process, PDI alters the conformation of integrin to a high affinity state and integrin binds tightly with the extracellular matrix (ECM) (integrin activation). Then, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), one of the downstream molecules of integrin, is phosphorylated, which increases matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) production. Finally, the cell secretes MMP-2, resulting in increased cell invasion. The PDI cycle was disturbed after the cells were treated with bacitracin. Bacitracin binding with reduced PDI led to lack of oxidation of reduced PDI. Only reduced PDI was present on the cell membrane after extending the bacitracin treatment time. Then, integrin was not activated, resulting in decreased FAK phosphorylation and MMP-2 production. Finally, MMP-2 secretion decreased, which disturbed cell invasion.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download