Abstract

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is common among various types of storkes; however, it is rare in young patients and patients who do not have any risk factors. In such cases, ICH is generally caused by vascular malformations, tumors, vasculitis, or drug abuse. Basal ganglia ICH is rarely related with distal lenticulostriate artery (LSA) aneurysm. Since the 1960s, a total of 29 distal LSA aneurysm cases causing ICH have been reported in the English literature. Despite of the small number of cases, various treatment methods have been attempted : surgical clipping, endovascular treatment, conservative treatment, superficial temporal artery-middle cerebral artery anastomosis, and gamma-knife radiosurgery. Here, we report two additional cases and review the literature. Thereupon, we discerned that young patients with deep ICH are in need of conventional cerebral angiography. Moreover, initial conservative treatment with follow-up cerebral angiography might be a good treatment option except for cases with a large amount of hematoma that necessitates emergency evacuation. If the LSA aneurysm still persists or enlarges on follow-up angiography, it should be treated surgically or endovascularly.

Hemorrhagic stroke constitutes around 10% to 15% of all strokes14). Generally, lobar intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is known to be caused by cerebral amyloid angiopathy, while deep ICH is often associated with hypertension41). However, research has indicated that abnormal vascular lesions may lead to deep ICH : arteriovenous malformation, moyamoya disease, aneurysm, and vasculitis. Among vascular lesions, rupture of the distal lenticulostriate artery (LSA) aneurysm is rare. Accordingly, considering the rarity of deep ICH caused by rupture of the distal LSA aneurysm, we report two additional cases thereof and review treatment strategies previously mentioned in the literature pertaining to the specific disease.

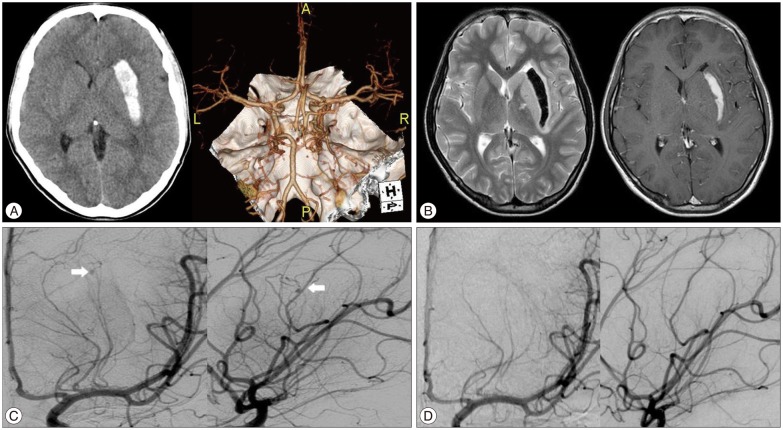

A 15-year-old man presented with a history of right side hemiparesis and dysphasia. He had been healthy with no connective tissue disease or infectious symptom. His laboratory finding did not reveal any thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy or vasculitis. Initial computed tomography (CT) scan at admission revealed an acute left lateral basal ganglia ICH. CT angiography showed an intact circle of Willis without abnormal vascular structures such as aneurysm, arteriovenous malformations, and moyamoya disease (Fig. 1A). After 2 days, magnetic resonance image (MRI) presented no expansion of hematoma without abnormal signal void and mass lesion adjacent to the hematoma (Fig. 1B). Because the patient was so young with no risk factors, we performed distal subtraction angiography (DSA) to identify its cause. The finding was a left lateral LSA small aneurysm with a size of 1.94×2.03 mm, in the most distal position (Fig. 1C). The patient's neurological symptoms were stable and follow-up brain CT showed no more hemorrhage expansion. Therefore, we decided on a conservative treatment strategy and followed up with angiography.

After 2 weeks, follow-up DSA was performed and demonstrated a complete disappearance of distal LSA aneurysm (Fig. 1D). The patient neurologic symptoms had improved and the patient was discharged.

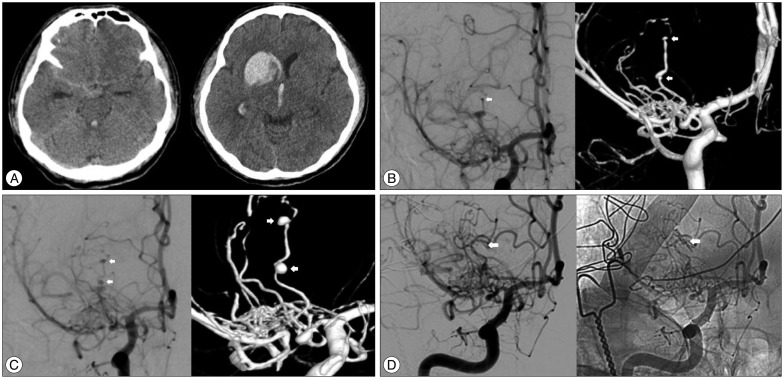

A 52-year-old man presented to our hospital with severe headache, nausea and vomitus. He had a history of asthma for 4 years, yet there was no history of hypertension, antiplatelet or anticoagulant assumption, heart disease, infectious disease, or head injury. At admission, physical examination revealed left side facial palsy (House and Backmann grade 2) and a conscious level of Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 14 (eye opening 3, verbal 5, motor 6). Initial CT scan revealed subtle basal cistern subarachnoid hemorrhage, more pronounced on the right, and right basal ganglia (caudate head) intracerebral hematoma with intraventricular extension without acute hydrocephalus (Fig. 2A). CT angiography showed right M1 occlusion with right distal LSA aneurysms, two small aneurysms arising from one parent artery. DSA showed right M1 proximal occlusion with an abnormal arterial network; furthermore, one parent artery of the right lateral LSA formed two small aneurysms (Fig. 2B).

Follow-up DSA, after 2 weeks of initial cerebral angiogram, was performed and showed an enlargement of the aneurysms (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, we decided on surgical treatment to avoid rebleeding. In the hybrid operation room, under frameless stereotactic guidance, gentle hematoma evacuation and clipping of the aneurysmal neck was done by a transcortical approach. Intraoperative angiogram confirmed successful aneurysm obliteration (Fig. 2D). Postoperatively, the patient was free of neurological symptoms and demonstrated excellent outcomes (mRS 1).

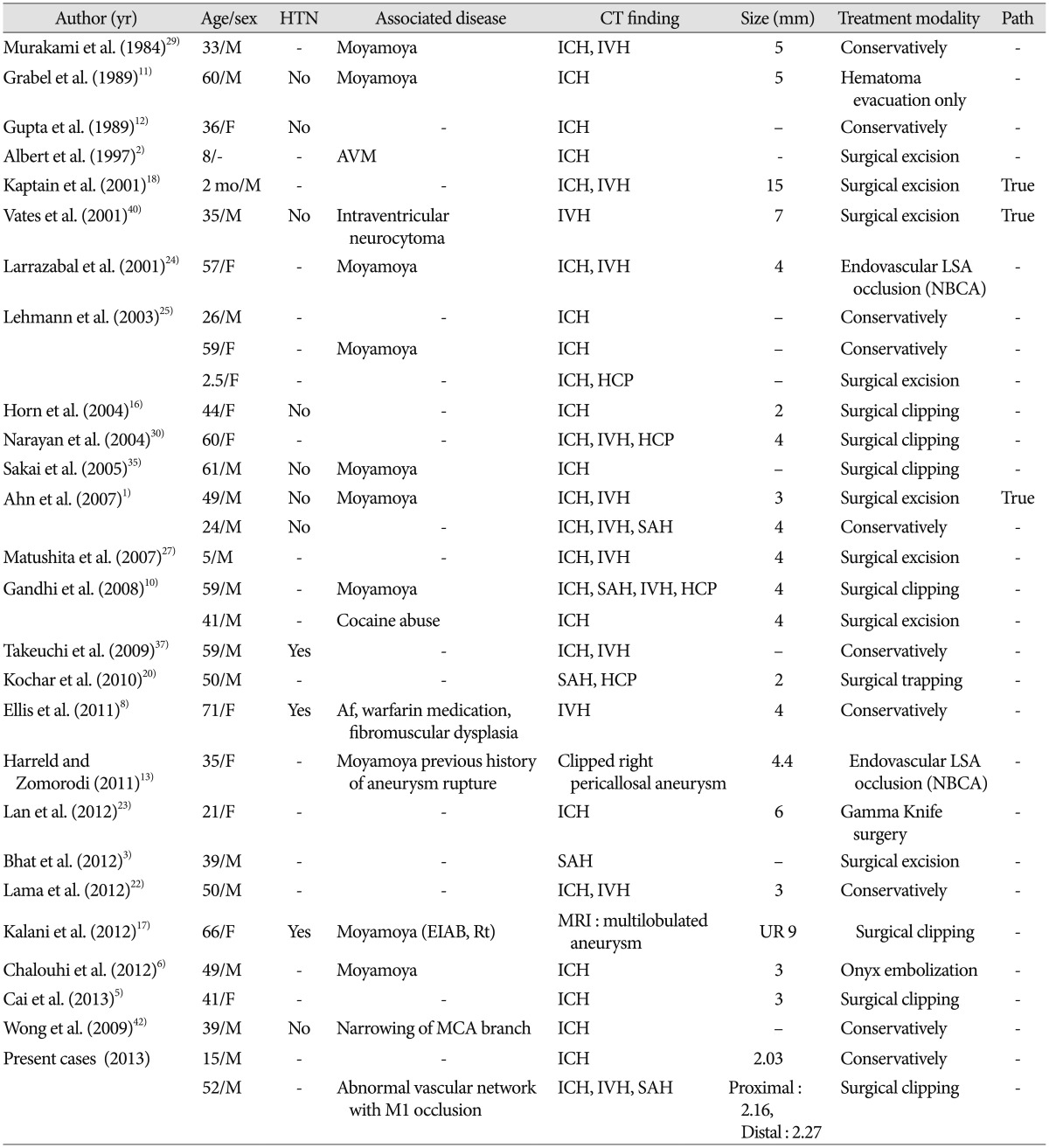

Aneurysms of distal LSA are relatively rare. Since the 1960s, thirty-nine English literatures associated with LSA aneurysm were reported123456789101112131516171819202122232425262729303132333435363738394042). Vargas et al.39) classified these aneurysms into three types based on anatomical location. According to this classification, distal LSA aneurysm is classified as type 3. A total of 56 LSA aneurysms were founded in 39 English literatures. Among them, true distal LSA aneurysms were 29 cases. Table 1 showed a summary of 31 distal LSA aneurysms including our cases12356810111213161718202223242527293035374042). The mean age of patients was 40.2 (2 month to 71 yrs). The male to female ratio was 17 to 13 (unknown 1). A history of hypertension was associated in 3 cases. Most ruptured distal LSA aneurysms occurred as a result of intraparenchymal hemorrhage (25 cases, 80.6%). Thirteen cases (41.9%) were associated with vascular lesions, such as moyamoya disease, probable moyamoya disease, arteriovenous malformation, and abnormal vascular network with M1 occlusion. This review revealed peculiar features of a younger mean age of presentation, no female predominance, and greater rates of underlying vascular lesions compared with other cerebral aneurysms. Therefore, young age with deep intracerebral hemorrhage patients should be suspicious of ruptured distal LSA aneurysm and associated vascular lesions. These patient groups should undergo conventional cerebral angiography. However, 11 patients, equivalent to 35%, were over 50 years old. Among them, 5 patients (16.1%) were over the age of 60. McCormick and Rosenfield28) reported that in 144 autopsy cases of massive brain hemorrhage, 58 patients had acceptable evidence of systemic hypertension, and among them, 21 patients (36%) involved other causes for the hemorrhage independent of the hypertension (aneurysm, angioma, cortical vein/dural sinus thrombosis, leukemia, sepsis with vasculitis, collagen-vascular disease, aplastic anemia with thrombocytopenia, and liver failure). This indicates that deep ICH may be due to distal LSA aneurysmal rupture or other underlying structural abnormalities, although deep ICH is commonly associated with pre-existing hypertension in elderly patients. Therefore, initial vessel study, such as CT angiography or MR angiography, may warrant consideration in patients over 50 years of age and who do not have any risk factors of ICH to detect treatable structural lesions.

Despite the small number of cases, various treatment strategies have been attempted. Surgical clipping or trapping were done in 8 patients, surgical excision in 8, endovascular treatment in 3 (NBCA in 1, Onyx in 2), gamma knife radiosurgery in 1, and only hematoma evacuation in 1. Other 10 patients were treated conservatively. In the surgical group, 3 cases demonstrated true aneurysmal pathology, which was typical saccular aneurysm. In the conservative treatment group, meanwhile, 8 cases showed spontaneous disappearance of the aneurysm. The mechanism for the formation of peripheral aneurysms may be related to hemodynamic stress. Distal peripheral aneurysm that disappeared on the follow-up angiogram may have been a pseudoaneurym resulting from previous rupture of a small artery27).

Distal LSA aneurysm are surgically and endovascularly challenging lesions. Surgically, these aneurysms can be located deep in the striatum, making intraoperative localization difficult. As well, aneurysm sizes can be very small, and fragile in nature. These reasons make it difficult to approach these lesions. Nevertheless, direct surgery is advantageous in that it reduces mass effects by the evacuated hematoma, and preserves parent artery patency by neck clipping in typical saccular aneurysm. Difficulty with intraoperative localization can be overcome by using frameless stereotactic guidance and intraoperative angiogram, as was the case here. Endovascularly, the acute angle and the small diameter of the LSA make selective catheterization of the aneurysm neck difficult. In 3 cases in the endovascular treated group, all three consisted of an occluded parent LSA, but there was no aggravation of neurologic symptoms such as contralateral hemiparesis. Compared with surgical intervention, less neuronal tissue damage is involved with endovascular treatment. Therefore, both surgical and endovascular treatment methods are acceptable treatment options in selected cases of distal LSA aneurysms.

Initial conservative treatment with careful follow-up conventional angiography may be warranted in pseudoaneurysmal lesions, whereas direct surgical or endovascular treatment should be considered in typical saccular aneurysms. If the LSA aneurysm still persists or enlarges on follow-up angiography, it should be treated surgically or endovascularly. We carefully suggest that initial conservative treatment with follow-up cerebral angiography might be a good treatment option except for cases with a large amount of hematoma that necessitates emergency evacuation.

References

1. Ahn JY, Cho JH, Lee JW. Distal lenticulostriate artery aneurysm in deep intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007; 78:1401–1403. PMID: 18024696.

2. Albert FK, Wirtz CR, Forsting M, Jansen O, Polarz H, Mittermaier G, et al. Image guided excision of a ruptured feeding artery "pedicle aneurysm" associated with an arteriovenous malformation in a child : case report. Comput Aided Surg. 19973; 2:5–10. PMID: 9148874.

3. Bhat DI, Shukla DP, Somanna S. Subarachnoid hemorrhage from a ruptured proximal lenticulostriate artery aneurysm. Neurol India. 2012; 60:128–129. PMID: 22406808.

4. Binning M, Duhon B, Couldwell WT. Partially thrombosed lateral lenticulostriate aneurysm presenting with embolic stroke : case illustration. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010; 5:190. PMID: 20121369.

5. Cai X, Han S, Feske SK, Chou SH. Pearls and oy-sters : small but consequential : intracerebral hemorrhage caused by lenticulostriate artery aneurysm. Neurology. 2013; 80:e89–e91. PMID: 23439707.

6. Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez LF, Dumont AS, Shah Q, Gordon D, et al. Onyx embolization of a ruptured lenticulostriate artery aneurysm in a patient with moyamoya disease. World Neurosurg. 2013; 80:436.e7–436.e10. PMID: 22484074.

7. Eddleman CS, Surdell D, Pollock G, Batjer HH, Bendok BR. Ruptured proximal lenticulostriate artery fusiform aneurysm presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage : case report. Neurosurgery. 2007; 60:E949. discussion E949. PMID: 17460507.

8. Ellis JA, D'Amico R, Altschul D, Leung R, Connolly ES, Meyers PM. Medial lenticulostriate artery aneurysm presenting with isolated intraventricular hemorrhage. Surg Neurol Int. 2011; 2:92. PMID: 21748044.

9. Endo M, Ochiai C, Watanabe K, Yoshimoto Y, Wakai S. [Ruptured peripheral lenticulostriate artery aneurysm in a child : case report]. No Shinkei Geka. 1996; 24:961–964. PMID: 8914158.

10. Gandhi CD, Gilad R, Patel AB, Haridas A, Bederson JB. Treatment of ruptured lenticulostriate artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2008; 109:28–37. PMID: 18590430.

11. Grabel JC, Levine M, Hollis P, Ragland R. Moyamoya-like disease associated with a lenticulostriate region aneurysm. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1989; 70:802–803. PMID: 2709122.

12. Gupta AK, Rao VR, Mandalam KR, Kumar S, Joseph S, Unni M, et al. Thrombosis of multiple aneurysms of a lateral lenticulostriate artery. An angiographic follow-up. Neuroradiology. 1989; 31:193–195. PMID: 2747901.

13. Harreld JH, Zomorodi AR. Embolization of an unruptured distal lenticulostriate aneurysm associated with moyamoya disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011; 32:E42–E43. PMID: 20075103.

14. Hemphill JC 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score : a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001; 32:891–897. PMID: 11283388.

15. Heran NS, Heran MS, Woolfenden AR. A corticosteroid-responsive aneurysmal lenticulostriate vasculopathy. Neurology. 2003; 61:1624–1625. PMID: 14663060.

16. Horn EM, Zabramski JM, Feiz-Erfan I, Lanzino G, McDougall CG. Distal lenticulostriate artery aneurysm rupture presenting as intraparenchymal hemorrhage : case report. Neurosurgery. 2004; 55:708. PMID: 16929579.

17. Kalani MY, Martirosyan NL, Nakaji P, Spetzler RF. Microsurgical clipping of an unruptured lenticulostriate aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci. 2012; 19:1578–1580. PMID: 22925414.

18. Kaptain GJ, Sheehan JP, Kassell NF. Lenticulostriate artery aneurysm in infancy. Case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2001; 94:538. PMID: 11235964.

19. Kidoguchi J, Chiba M, Murakami T, Saiki I, Kanaya H, Tazawa M, et al. [A case of systemic lupus erythematosus associated with an aneurysm of the lenticulostriate artery]. No Shinkei Geka. 1987; 15:1221–1225. PMID: 3325845.

20. Kochar PS, Morrish WF, Hudon ME, Wong JH, Goyal M. Fusiform lenticulostriate artery aneurysm with subarachnoid hemorrhage : the role for superselective angiography in treatment planning. Interv Neuroradiol. 2010; 16:259–263. PMID: 20977857.

21. Kuroda S, Houkin K, Kamiyama H, Abe H. Effects of surgical revascularization on peripheral artery aneurysms in moyamoya disease : report of three cases. Neurosurgery. 2001; 49:463–467. discussion 467-468PMID: 11504126.

22. Lama S, Dolati P, Sutherland GR. Controversy in the management of lenticulostriate artery dissecting aneurysm : a case report and review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2014; 81:441.e1–441.e7. PMID: 23246740.

23. Lan Z, Li J, You C, Chen J. Successful use of Gamma Knife surgery in a distal lenticulostriate artery aneurysm intervention. Br J Neurosurg. 2012; 26:89–90. PMID: 21767129.

24. Larrazabal R, Pelz D, Findlay JM. Endovascular treatment of a lenticulostriate artery aneurysm with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Can J Neurol Sci. 2001; 28:256–259. PMID: 11513346.

25. Lehmann P, Toussaint P, Depriester C, Legars D, Deramond H. [Lenticulostriate aneurysms. Radioclinical study]. J Neuroradiol. 2003; 30:115–120. PMID: 12717298.

26. Maeda K, Fujimaki T, Morimoto T, Toyoda T. Cerebral aneurysms in the perforating artery manifesting intracerebral and subarachnoid haemorrhage--report of two cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001; 143:1153–1156. PMID: 11731866.

27. Matushita H, Amorim RL, Paiva WS, Cardeal DD, Pinto FC. Idiopathic distal lenticulostriate artery aneurysm in a child. J Neurosurg. 2007; 107(5 Suppl):419–424. PMID: 18459908.

28. McCormick WF, Rosenfield DB. Massive brain hemorrhage : a review of 144 cases and an examination of their causes. Stroke. 1973; 4:946–954. PMID: 4765001.

29. Murakami H, Mine T, Nakamura T, Aki T, Suzuki K. [Intracerebral hemorrhage due to rupture of true aneurysms of the lenticulostriate artery in moyamoya disease. Case report]. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1984; 24:794–799. PMID: 6084185.

30. Narayan P, Workman MJ, Barrow DL. Surgical treatment of a lenticulostriate artery aneurysm. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004; 100:340–342. PMID: 15086244.

31. Ohta H, Ito Z, Nakajima K, Fukasawa H, Uemura K. [A case report of ruptured lenticulostriate artery aneurysm with arteriovenous malformation (author's transl)]. No To Shinkei. 1980; 32:839–846. PMID: 7470330.

32. Oka K, Maehara F, Tomonaga M. Aneurysm of the lenticulostriate artery--report of four cases. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1991; 31:582–585. PMID: 1723172.

33. Okuma A, Oshita H, Funakoshi T, Shikinami A, Yamada H. [A case of aneurysm in the cerebral myoyamoya vessel--aneurysmal rupture during cerebral angiography and spontaneous regression of the aneurysm (author's transl)]. No Shinkei Geka. 1980; 8:181–185. PMID: 7360320.

34. Petrela M, Xhumari A, Azdurian E, Vreto G. [Aneurysm of the terminal part of the lenticulostriate artery]. Neurochirurgie. 1992; 38:50–52. PMID: 1560885.

35. Sakai K, Mizumatsu S, Terasaka K, Sugatani H, Higashi T. Surgical treatment of a lenticulostriate artery aneurysm. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2005; 45:574–577. PMID: 16308516.

36. Schürmann K, Brock M, Samii M. Circumscribed hematoma of the lateral ventricle following rupture of an intraventricular saccular arterial aneurysm. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1968; 29:195–198. PMID: 5673318.

37. Takeuchi S, Takasato Y, Masaoka H, Hayakawa T, Otani N, Yoshino Y, et al. Bilateral lenticulostriate artery aneurysms. Br J Neurosurg. 2009; 23:543–544. PMID: 19718551.

38. Tsai YH, Wang TC, Weng HH, Wong HF. Embolization of a ruptured lenticulostriate artery aneurysm. J Neuroradiol. 2011; 38:242–245. PMID: 21257203.

39. Vargas J, Walsh K, Turner R, Chaudry I, Turk A, Spiotta A. Lenticulostriate aneurysms : a case series and review of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015; 7:194–201. PMID: 24574545.

40. Vates GE, Arthur KA, Ojemann SG, Williams F, Lawton MT. A neurocytoma and an associated lenticulostriate artery aneurysm presenting with intraventricular hemorrhage : case report. Neurosurgery. 2001; 49:721–725. PMID: 11523685.

41. Viswanathan A, Rakich SM, Engel C, Snider R, Rosand J, Greenberg SM, et al. Antiplatelet use after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2006; 66:206–209. PMID: 16434655.

42. Wong GK, Chou HL, Poon WS, Zhu XL, Yu SC, Ahuja AT. Spontaneous resolution of an aneurysm arising from a penetrating branch of the middle cerebral artery. J Clin Neurosci. 2009; 16:601–602. PMID: 19201613.

Fig. 1

A : Computed tomography (CT) scan at admission shows left putaminal intracerebral hemorrhage (left), and CT angiography shows any abnormal vascular lesion (right). B : Initial magnetic resonance images (MRI) demonstrate no abnormal signal void in T2WI (left) and enhancing mass lesion adjacent to the hematoma in T1 contrast enhanced image (right). C : Initial left internal carotid artery angiogram shows a small aneurysm (arrows) at the distal lateral lenticulostriate artery (LSA) (left : AP view, right : lateral view). D : Follow up angiography after 2 weeks demonstrates complete disappearance of the distal lateral LSA aneurysm (left : AP view, right : lateral view). AP : anterorposterior.

Fig. 2

A : Non contrast CT at admission shows subtle basal cistern subarachnoid hemorrhage (left), and right caudate head intracerebral hematoma with intraventricular extension without acute hydrocephalus (right). B : First conventional cerebral angiography (AP view, left) and 3D reconstruction (right). The right M1 proximal trunk is aplastic, and distal flow consists of an abnormal arterial network. Aneurysm occurred in one parent artery of the right LSA, forming two small aneurysms. C : Follow-up cerebral angiography after 2 weeks shows enlargement of the aneurysms. (right : AP view, left : 3D reconstruction). D : Intraoperative cerebral angiography (AP view, left : distal subtraction angiography, right : native image) shows complete obliteration of aneurysmal sac by clips. AP : anteroposterior, LSA : lenticulostriate artery.

Table 1

Summary of literature review of the distal lenticulostriate aneurysm

Af : arterial fibrillation, HTN : hypertension, path : pathology, F : female, M : male, ICH : intracerebral hemorrhage, IVH : intraventricular hemorrhage, SAH : subarachnoid hemorrhage, HCP : hydrocephalus, Rt : right, Lt : left, UR : unrupture, R : rupture, AVM : arteriovenous malformation, SLE : systemic lupus erythematosus, EVD : extra-ventricular drainage, EIAB : external-internal carotid artery bypass, EDAS : encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis, LSA : lenticulostriate artery, NBCA : N-butyl cyanoacrylate

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download