Abstract

Objective

Ossification of the ligamentum nuchae (OLN) is usually asymptomatic and incidentally observed in cervical lateral radiographs. Previous literatures reported the correlation between OLN and cervical spondylosis. The purpose of this study was to elucidate the clinical significance of OLN with relation to cervical ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL).

Methods

We retrospectively compared the prevalence of OPLL in 105 patients with OLN and without OLN and compared the prevalence of OLN in 105 patients with OPLL and without OPLL. We also analyzed the relationship between the morphology of OLN and involved OPLL level. The OPLL level was classified as short (1-3) or long (4-6), and the morphologic subtype of OLN was categorized as round, rod, or segmented.

Results

The prevalence of OPLL was significantly higher in the patients with OLN (64.7%) than without OLN (16.1%) (p=0.0001). And the prevalence of OLN was also higher in the patients with OPLL (54.2%) than without OPLL (29.5%) (p=0.0002). In patients with round type OLN, 5 of 26 (19.2%) showed long level OPLL, while in patients with larger type (rod and segmented) OLN, 22 of 42 (52.3%) showed long level OPLL (p=0.01).

Conclusion

There was significant relationship between OLN and OPLL prevalence. This correlation indicates that there might be common systemic causes as well as mechanical causes in the formation of OPLL and OLN. The incidentally detected OLN in cervical lateral radiograph, especially larger type, might be helpful to predict the possibility of cervical OPLL.

There are various ligaments around the vertebral column, such as the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL), ligamentum flavum, and ligamentum nuchae of the cervical spine. These ligaments may become ossified, paravertebral ligamentous ossification is defined by ossified ligaments around the spinal canal, including diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), and ossification of ligamentum flavum (OLF).

The ligamentum nuchae is a midline intervertebral syndesmosis that spans the cervical spine, and its posterior border is firmly attached to the external occipital protuberance and to the spinous process of C7. Clinically, ossification of the ligamentum nuchae (OLN) is usually asymptomatic and usually incidentally observed in cervical lateral radiographs. OLN is observed more often in male patients than female patients and the incidence increases as the patient's age increases19). OLN may occur as a result of cervical instability caused by trauma or chronic overload2311).

Some investigators have suggested that OLN may be a paravertebral ligamentous ossification syndrome121820). Many previous reports identified the associations and coexistence between DISH, OPLL, and OLF451415). However, there are few studies demonstrating the relationship between OLN and OPLL. In 1980, Izawa6) reported that the incidence of OLN in Japanese and Korean people is higher than in Americans and Germans and suggested that this difference may be due to the higher incidence of OPLL in Asian patients.

Hormonal and metabolic abnormalities have been attributed to the pathogenesis of OPLL, such as vitamin D resistant hypophosphatemic rickets, hypoparathyroidism and abnormal glucose intolerance or diabetes mellitus1028). However, the cause of OPLL is still unknown. We have often observed the coincidence of OLN and OPLL in spine patients.

To evaluate the clinical significance of OLN with relation to OPLL, we hypothesize that systemic conditions related to OPLL pathogenesis may increase the coincidence of OLN and OPLL. Our hypotheses were as follows : 1) in patients with OLN, the coincidence of cervical OPLL is higher than in patients without OLN; 2) in patients with OPLL, the coincidence of OLN is higher than in patients without OPLL; and 3) the number of involved OPLL may increase as the size of OLN increases.

Retrospectively, we reviewed medical records and radiographs of the cervical degenerative disease patients (n=950) who underwent cervical X-ray and cervical spine computed tomography (CT) in our hospital from 2008 to 2014. Cervical degenerative disease included cervical disc disease, cervical spondylosis, and cervical OPLL. We excluded patients with trauma, infection, deformity, or previous cervical laminectomy.

Among these 950 patients with cervical X-ray and cervical spine CT, we selected patients who showed OLN in lateral cervical film. A total of 105 patients with OLN were enrolled in this study. The incidence of OLN in this study is 11.1% (105/950). Another 105 patients without OLN were selected and they were matched with patients with OLN for age and sex on a 1 : 1 basis to minimize the confounding factors. In both group, we reviewed the prevalence of cervical OPLL.

Among these 950 patients with cervical X-ray and cervical spine CT, we selected patients who underwent surgery for OPLL. A total of 105 patients with OPLL were included. The non-OPLL patients were matched with patients with OPLL for age and sex on 1 : 1 basis. In both groups, we reviewed the prevalence of OLN on radiograph.

Cervical OPLL was diagnosed with three-demensional (3D) spine CT and the diagnosis of OPLL was based on previously determined criteria24) by the neuroradiologist. The extent of cervical OPLL involved was determined by the number of cervical spine levels with OPLL. Patients ranged from 1 to 6 levels, and we divided them into 2 groups, a short level (1-3 levels) OPLL group and a long level (4-6 levels) OPLL group.

Our Institutional Review Board approved this study for retrospective review of data.

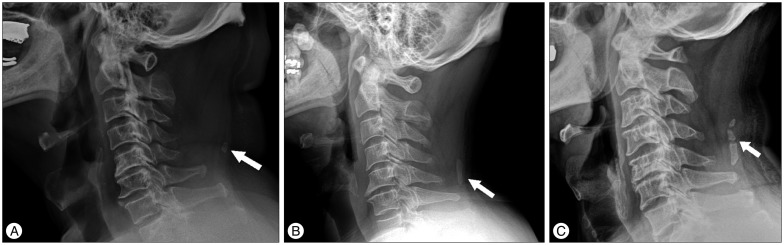

We regarded plain radiopaque masses in the posterior aspect of cervical vertebrae on cervical lateral radiograph as OLN. We observed that OLN had some common morphologic patterns and were able to subdivide OLN into round, rod, and segmented types according to the shape of ossification (Fig. 1).

In some cases it was difficult to determine whether the OLN was round or rod type. When the longest axis of round OLN exceeded 10 mm in the sagittal plane, we classified them as rod type OLN. Segmented type means discontinuous OLN, and the shape of separated parts is similar. We noticed that as the type of OLN changes from round to rod type or to segmented type, the size of OLN increases in the sagittal plane. All of these findings were confirmed by observations of bone density on cervical CT and only then were regarded as OLN (Fig. 2).

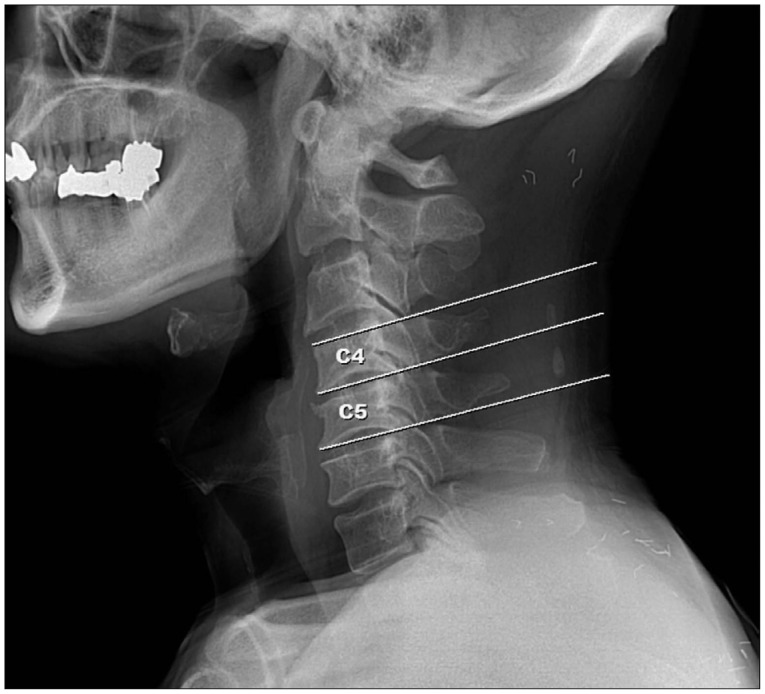

The level of ossification was determined by drawing horizontal lines along the upper and lower ends of cervical vertebral bodies. For example, if the OLN was located below the horizontal line along upper end of C4 body and above the horizontal line along lower end of C5 body, it was determined to be located in C4, 5 level (Fig. 3).

Baseline characteristics were analyzed using paired t-tests. We compared the prevalence of OPLL in patients with OLN and without OLN using Pearson's chi-square test. And we also compared the prevalence of OLN in patients with OPLL and without OPLL. The relationships between the number of OPLL levels and types of OLN were also investigated with Pearson's chi-square test. Statistical significance was defined as p values less than 0.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

For patients with OLN and without OLN, the mean age was 56.89 years (range from 39 to 77 years) and the numbers of males and females were 81 and 24, respectively (Table 1). The most common location of OLN was at the C5 level (50.7%) and the most common type was round (40.9%). The prevalence of OLN increased with patient age. From 30 to 39 years of age, the prevalence of OLN was 25%; from 40 to 49, the prevalence was 33.3%; from 50 to 59, the prevalence was 41.86; from 60 to 69, the prevalence was 48.14%; and from 70 to 79, the prevalence was 50%.

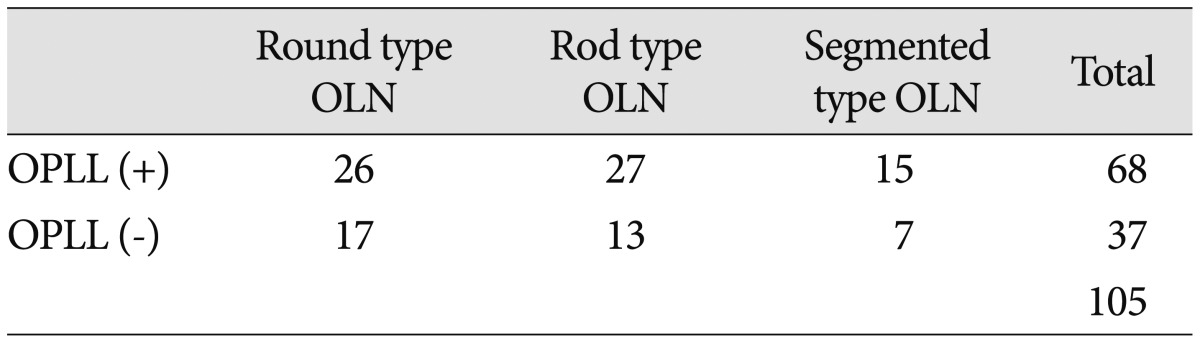

In the patients with OLN, 68 patients (64.7%) were identified as having OPLL on radiographs, while in the patients without OLN, 17 patients (16.1%) were identified as having OPLL. The prevalence of OPLL was almost 4 times greater in the patients with OLN than without OLN, which was significantly different (p=0.0001) (Table 1). The relative risk was 4 and odds ratio was 9.5135 (95% CI 4.9382-18.3278). The prevalence of OPLL in each type of OLN is shown in Table 2.

We hypothesized that as the proportion of larger types of OLN (e.g., rod or segmented type) increase, the numbers of involved OPLL levels would increase. The patients with larger types of OLN showed a higher incidence of long level OPLL than with round type OLN, which was statistically significant (p=0.01). In patients with round type OLN, 5 of 26 (19.2%) showed long level OPLL, while in patients with rod and segmented type OLN, 22 of 42 (52.3%) showed long level OPLL (Table 3).

For patients with OPLL and without OPLL, the mean age was 55.85 years (range from 35 to 78 years) and the numbers of males and females were 67 and 38, respectively (Table 4).

Among a total of 210 patients, OLN was observed in 88 (41.9%) in radiographs.

In the patients with OPLL, 57 patients (54.2%) were identified as having OLN on radiographs, while in without OPLL, 31 patients (29.5%) were identified as having OLN. The prevalence of OLN was almost 2 times greater in OPLL group than non-OPLL group, which was significantly different (p=0.0002) (Table 4). The relative risk was 1.8387 and odds ratio was 2.835 (95% CI 1.605-5.005).

Previous literatures reported that trauma, chronic overload in cervical spinal ligament, age, and systemic conditions might cause OLN21820). The incidence of spinal ligament ossification in Asian race is higher than in Caucasian race. Izawa6) reported that the incidence of OLN was between 10.2% and 27.6% in Japanese patients and 11.3% in Koreans9). Shingyouchi et al.20) found that the incidence of OLN in Japanese males was 23.3%. In our study, the incidence of OLN was 11.1%, which was similar to previous study. Trauma or overload in cervical spine may cause injury to ligamentum nuchae and chronic accumulation of the injury may cause cervical instability2182021). In general, cervical instability leads to osteophyte formation, disc degeneration in cervical spine. And injury to ligamentum nuchae may cause OLN. This explains the higher incidence of OLN in our study. Tsai et al.23) also reported correlation between OLN and clinical cervical disorders such as cervical spondylosis or disc degeneration.

Types of OLN were classified into round, rod, and segmented types in this study. Previously, An studied 240 patients with OLN using this classification. Among their sample, rod type was observed in 49.2%, round type in 30.4%, and segmented type in 20.4% of patients. In the third decades of life, round type OLN was the most common while the rod type was the most common after the fourth decade of life. They reported that degenerative changes with aging might play a role in the development and progression of OLN1).

In our study, the prevalence of OLN was higher in male patients than in female patients, and increased with patient age in both groups as previous studies. OLN appeared mostly at the levels of the cervical spine where mobility is greatest (C5). If we assume that men are more physically active than women, our results suggest that chronic overload of the cervical spine due to aging and cervical motion promotes OLN, as suggested in previous studies119).

OPLL is characterized by growth of the posterior longitudinal ligament with the development of ossification centers. It is common in Asia, particularly in Japan, and the incidence based on radiography is reported to be 2% in Asians24). The incidence was almost two times greater in men than women and increased with advancing age, particularly in people age more than 50 years6927). Ligamentum nuchae is considered to maintain the lordotic alignment and limit the movements of cervical spine81317). Aging and physical activity cause injury to ligamentum nuchae114). This injury breaks cervical lordotic alignment and compensatory ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament might develop to maintain the lordotic alignment, which needs further study and proof.

However, the underlying cause of OPLL is still unclear and is believed to be influenced by several genetic and hormonal factors7927). In our study, the prevalence of OPLL in patients with OLN (64.7%) was significantly higher than in without OLN (16.1%) and the prevalence of OLN in OPLL patients (54.2%) was significantly higher than in non-OPLL patients (29.5%). And patients with larger types of OLN were more prone to have long level OPLL than with round type OLN. The mean age of patients with round type OLN was 55.4 years, while that of larger types of OLN was 56.7 years; this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.49). Because OLN can be easily detected with cervical lateral radiograph, this correlation between OLN and OPLL might be helpful to clinicians to consider the possibility of OPLL in patients with OLN.

Recently, some investigators have proposed that the OLN may be a type of spinal ligament ossification syndrome121820). According to recent studies, spinal ligament ossification syndrome including OPLL, OLF, and DISH, is a multifactorial disease in which complex genetic and environmental factors interact162226). Many previous reports have identified the etiologic associations of DISH, OPLL, and OLF451415). Calcium regulating hormones, glucose metabolism hormones, and growth factors such as bone morphogenic hormones and tumor growth factor-β1 are thought to be important in the pathogenesis of the ossification of the spinal ligament, although the underlying mechanisms remain uncertain11).

However, studies demonstrating the relationship between OPLL and OLN are limited. In 1996, Shingyouchi et al.20) reported that ossification of anterior longitudinal ligament (OALL), OLN, and OPLL had etiologic similarities in terms of age, sex, and obesity, but that OLN had additional etiologies because OLN is more related to dynamic stress. Wang et al.25) reported that incidence of OLN was almost 2 times greater in patients with OPLL than in other spondylosis patients and sex, aging, and OPLL were related with the formation of OLN, which was concordant with our results. The systemic factors related to OPLL pathogenesis may promote the development and progression of OLN, which is need to be demonstrated in the future study.

The limitations of this study were that we were unable to perform hormonal studies in OLN patients because the study was retrospective. Further prospective studies regarding the relationships between OLN and systemic hormones may be needed to elucidate the common pathogenic causes of OPLL and OLN.

The prevalence of OPLL was higher in patients with OLN than in patients without OLN and the larger types of OLN (rod and segmented type) was related with long level OPLL (3-6 levels). This indicates that OPLL and OLN may have common pathogenesis such as hormonal or metabolic causes. The incidentally detected OLN in cervical lateral radiograph might be helpful to predict the possibility of cervical OPLL. When a clinician detects OLN, especially larger types, in patients with neck pain, radiculopathy, or myelopathy, one should perform further diagnostic evaluations of such patients, which may facilitate proper treatment.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by research funds of Chonbuk National University in 2014. This paper was supported by Fund of Biomedical Research Institute, Chonbuk National University Hospital.

References

1. An CH. Study on the nuchal ligament ossification on lateral cephalometric radiograph. Korean J Oral Maxillofac Radiol. 2009; 39:7–11.

2. Chazal J, Tanguy A, Bourges M, Gaurel G, Escande G, Guillot M, et al. Biomechanical properties of spinal ligaments and a histological study of the supraspinal ligament in traction. J Biomech. 1985; 18:167–176. PMID: 3997901.

3. Cheng ST. The relation between the injury of nuchal ligament and cervical spondylosis. J Spinal Surg. 2004; 2:241–242.

4. Ehara S, Shimamura T, Nakamura R, Yamazaki K. Paravertebral ligamentous ossification : DISH, OPLL and OLF. Eur J Radiol. 1998; 27:196–205. PMID: 9717635.

5. Hukuda S, Mochizuki T, Ogata M, Shichikawa K. The pattern of spinal and extraspinal hyperostosis in patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and the ligamentum flavum causing myelopathy. Skeletal Radiol. 1983; 10:79–85. PMID: 6612370.

6. Izawa K. [Comparative roentgenographical study on the incidence of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and other degenerative changes of the cervical spine among Japanese, Koreans, Americans and Germans (author's transl)]. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1980; 54:461–474. PMID: 6775031.

7. Jun JK, Kim SM. Association study of fibroblast growth factor 2 and fibroblast growth factor receptors gene polymorphism in Korean ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament patients. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012; 52:7–13. PMID: 22993671.

8. Kadri PA, Al-Mefty O. Anatomy of the nuchal ligament and its surgical applications. Neurosurgery. 2007; 61(5 Suppl 2):301–304. discussion 304PMID: 18091243.

9. Katayama H, Nanjo T, Saito M, Sakuyama K. [Radiological analysis of the ossifications of the nuchal ligaments (ONL) (author's transl)]. Rinsho Hoshasen. 1982; 27:91–95. PMID: 6804669.

10. Kobashi G, Washio M, Okamoto K, Sasaki S, Yokoyama T, Miyake Y, et al. High body mass index after age 20 and diabetes mellitus are independent risk factors for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine in Japanese subjects : a case-control study in multiple hospitals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004; 29:1006–1010. PMID: 15105673.

11. Luo J, Wei X, Li JJ. [Clinical significance of nuchal ligament calcification and the discussion on biomechanics]. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2010; 23:305–307. PMID: 20486389.

12. Mine T, Kawai S. Ultrastructural observations on the ossification of the supraspinous ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995; 20:297–302. PMID: 7732465.

13. Mitchell BS, Humphreys BK, O'Sullivan E. Attachments of the ligamentum nuchae to cervical posterior spinal dura and the lateral part of the occipital bone. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1998; 21:145–148. PMID: 9567232.

14. Ono M, Russell WJ, Kudo S, Kuroiwa Y, Takamori M, Motomura S, et al. Ossification of the thoracic posterior longitudinal ligament in a fixed population. Radiological and neurological manifestations. Radiology. 1982; 143:469–474. PMID: 7071349.

15. Resnick D, Guerra J Jr, Robinson CA, Vint VC. Association of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and calcification and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978; 131:1049–1053. PMID: 104572.

16. Sakou T, Taketomi E, Matsunaga S, Yamaguchi M, Sonoda S, Yashiki S. Genetic study of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine with human leukocyte antigen haplotype. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991; 16:1249–1252. PMID: 1749995.

17. Sasai K, Saito T, Akagi S, Kato I, Ogawa R. Cervical curvature after laminoplasty for spondylotic myelopathy--involvement of yellow ligament, semispinalis cervicis muscle, and nuchal ligament. J Spinal Disord. 2000; 13:26–30. PMID: 10710145.

18. Scapinelli R. Localized ossifications in the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments of adult man. Rays. 1988; 13:29–33. PMID: 3147497.

19. Scapinelli R. Sesamoid bones in the ligamentum nuchae of man. J Anat. 1963; 97:417–422. PMID: 14047360.

20. Shingyouchi Y, Nagahama A, Niida M. Ligamentous ossification of the cervical spine in the late middle-aged Japanese men. Its relation to body mass index and glucose metabolism. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996; 21:2474–2478. PMID: 8923634.

21. Takeshita K, Peterson ET, Bylski-Austrow D, Crawford AH, Nakamura K. The nuchal ligament restrains cervical spine flexion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004; 29:E388–E393. PMID: 15371718.

22. Terayama K. Genetic studies on ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989; 14:1184–1191. PMID: 2513651.

23. Tsai YL, Weng MC, Chen TW, Hsieh YL, Chen CH, Huang MH. Correlation between the ossification of nuchal ligament and clinical cervical disorders. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2012; 28:538–544. PMID: 23089319.

24. Tsuyama N. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984; (184):71–84. PMID: 6423334.

25. Wang H, Zou F, Jiang J, Lu F, Chen W, Ma X, et al. Analysis of radiography findings of ossification of nuchal ligament of cervical spine in patients with cervical spondylosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014; 39:E7–E11. PMID: 24270934.

26. Yamaguchi M. [Genetic study on OPLL in the cervical spine with HLA haplotype]. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1991; 65:527–535. PMID: 1955798.

27. Yanagihara M. [An epidemiological study on the ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament of the spine]. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1986; 60:187–202. PMID: 3088185.

28. Yoshikawa S, Shiba M, Suzuki A. Spinal-cord compression in untreated adult cases of vitamin-D resistant rickets. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968; 50:743–752. PMID: 5658559.

Fig. 1

Simple cervical lateral films of OPLL patients. A : A 52-year-old male patient with round type OLN (arrow). B : A 61-year-old male patient with rod type OLN (arrow). C : A 55-year-old male patient with segmented type OLN (arrow). As the type of OLN changes from round to rod to segmented, the size of OLN increases at the sagittal plane. OPLL : ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament, OLN : ossification of nuchal ligament.

Fig. 2

Computed tomography of OPLL patients shows that patients with larger OLN are more prone to having multiple levels of OPLL. A : A 55-year-old male patient has round type OLN (white arrow) with short level OPLL at the C4, 5 (black arrow). B : A 52-year-old male patient has segmented type OLN (white arrow) with long level OPLL at the C4-7 (black arrow). OPLL : ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament, OLN : ossification of nuchal ligament.

Fig. 3

The level of ossification was determined by the horizontal line along the endplate of each vertebral body.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download