Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine the efficacy and perioperative complications associated with lumbar spinal fusion surgery, focusing on geriatric patients in the Republic of Korea.

Methods

We retrospectively investigated 485 patients with degenerative spinal diseases who had lumbar spinal fusion surgeries between March 2006 and December 2010 at our institution. Age, sex, comorbidity, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, fusion segments, perioperative complications, and outcomes were analyzed in this study. Risk factors for complications and their association with age were analyzed.

Results

In this study, 81 patients presented complications (16.7%). The rate of perioperative complications was significantly higher in patients 70 years or older than in other age groups (univariate analysis, p=0.015; multivariate analysis, p=0.024). The perioperative complications were not significantly associated with the other factors tested (sex, comorbidity, ASA class, and fusion segments). Post-operative outcomes of lumbar spinal fusion surgeries for the patients were determined on the basis of MacNab's criteria (average follow up period : 19.7 months), and 412 patients (85.0%) were classified as having "excellent" or "good" results.

Conclusion

Increasing age was an important risk factor for perioperative complications in patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion surgery, whereas other factors were not significant. However, patients' satisfaction or return to daily activities when compared with younger patients did not show much difference. We recommend good clinical judgment as well as careful selection of geriatric patients for lumbar spinal fusion surgery.

Go to :

As the size of the geriatric population increases, the number of elderly patients diagnosed with painful degenerative diseases of the lumbar spine requiring surgery is expected to rise concomitantly. Many patients require lumbar spinal fusion surgery with instrumentation along with decompression to treat the degenerative lumbar disease. Often, patient age is a major factor in deciding to which extent surgeries could or should be performed, and it is perceived that morbidity is increased with extensive surgeries in older patients32). The geriatric population may be at increased risk for complications because of age and age-associated medical conditions. However, there is a lack of studies addressing the perioperative complications in elderly patients with decompression, arthrodesis of the lumbar spine, and the post operative outcomes of lumbar spinal fusion surgeries24). A review of literature reveals controversy over the safety of lumbar spinal fusion surgery in the elderly due to varying findings on the risk. Several researchers raised concerns over increased morbidity, cautioning against spinal surgery in the older population3,17). The goal of this study was to evaluate; 1) the complication rate in relation to perioperative complications, general factors such as age, sex, comorbidity, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and fusion segments involved, and 2) examine the clinical outcomes of lumbar spinal fusion surgery for degenerative lumbar diseases for patients 70 years and older in contrast to patients younger than 65 year of age.

Go to :

In this study, the patient population of a specific age group was selected based on the type of surgeries the patients received in a specific time period. The 485 patients underwent lumbar spinal fusion surgeries between March 2006 to December 2010. Patient population was divided into two groups according to the definition of "geriatric" : 70 years and older (group 1), and younger than 65 years (group 2). The post-operative follow-up period was more than 12 months. Lumbar spinal fusion surgeries were performed by 4 neurosurgeons at a single institute. We included patients with degenerative spine diseases, and excluded patients with age between 65 and 69 years, spine traumas, spinal revision surgeries, and spine tumors in order to avoid unexpected co-morbidities. Data related to these patients were evaluated by a single observer using the standard hospital charts, outpatient notes, electronic medical records, operative reports, and preoperative and postoperative imaging studies. The following demographic variables were evaluated : age, sex, treatable or non-treatable medical co-morbidities, the preoperative ASA classification of physical status, and segment of fusion.

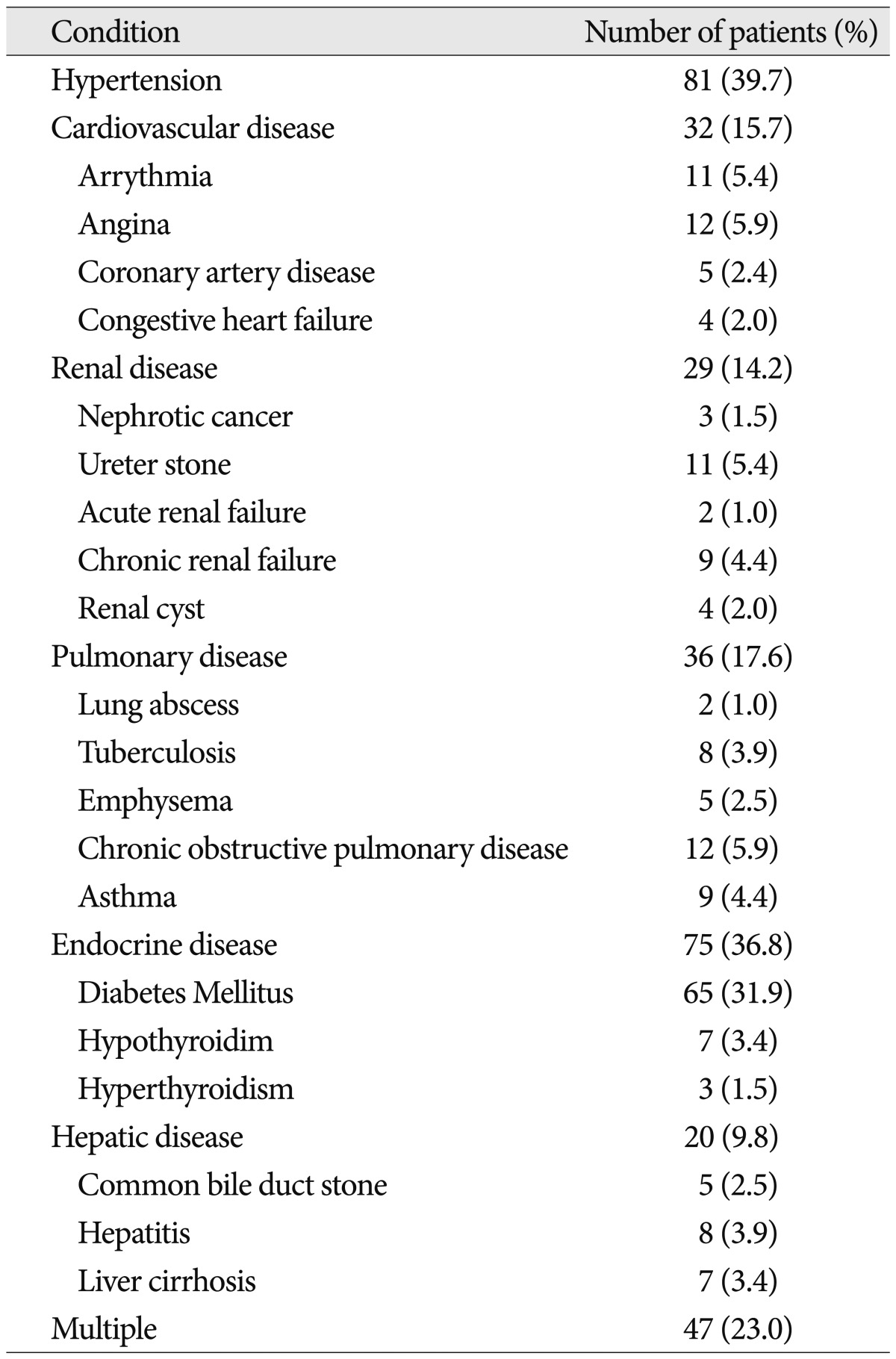

All patients were evaluated for co-morbidities such as cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, hepatic problems and diabetes mellitus. Co-morbidities were subdivided as follows : cardiovascular (hypertension, arrhythmia, angina, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure), renal (nephrotic cancer, ureter stone, renal cyst and acute or chronic renal failure), pulmonary (lung abscess, tuberculosis, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma), hepatic (common bile duct stones, hepatitis and liver cirrhosis) and endocrine (diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism).

The standard surgical procedure was in steps sequenced as follows : partial hemilaminectomy, transpedicular screw fixation, and both posterior lumber interbody fusion with cage and posterolateral fusion. The mean operation time was 198.2 minutes, the mean estimated blood loss was 325.8 cc, and the mean transfusion was 185.7 cc. In general, surgeries were performed in degenerative cases when conservative treatment over three months failed to improve the patients' symptoms. In this study, the four neurosurgeons' techniques were interchangeable.

Patients were ambulated from the second postoperative day with rigid molded plastic braces or lumbar corsets. Initially, the patients were treated with analgesia for control of acute pain by intravenous injection, and then weaned to mild oral narcotic therapy and NSAIDs that were discontinued as quickly as possible.

The term "complication" in this study is defined broadly and differently from published literature. In this study, a complication was any event requiring specific management during the perioperative period, including the intra-operative and post-operative periods. All complications were verified by retrospective chart reviews.

The patients enrolled in this study were followed-up for at least 12 months postoperatively. The average follow-up periods were 19.7 months. We used MacNab's criteria to evaluate objective neurologic improvement.

The frequency analysis, simple and multiple logistic regression analysis, and χ2 test were done using SPSS ver. 19.0 logistics program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Frequency analyses tested demographic characteristics. Logistic regression analyses were done to investigate whether complications were effected by age, sex, comorbidity, ASA class, or fusion segments. Fisher's exact test was carried out to compare how the complications affected the MacNab's criteria results after final follow-up. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. For each variable, odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated.

Go to :

During the five-year study period, the 485 patients met the inclusion criteria and underwent lumbar spinal fusion surgeries (Table 1). Of these, 156 patients (32.2%) were male and 329 (67.8%) were female, and there were 174 patients (35.9%) in group 1 and 311 patients (64.1%) in group 2. The mean age was 57.5 years. (group 1, 72.7 years; group 2, 48.9 years). The number of patients in the age group 70-75, 75-79, and 80-85 were 92, 56, and 26, respectively. 204 (42.1%) of the patients had comorbidities. The general condition of those patients varied by ASA class : ASA class I (303 patients, 62.5%), ASA II (149 patients, 30.7%) and ASA III (33 patients, 6.8%). Fusion segment levels were categorized as 1 segment (247 patients, 50.9%), 2 segments (179 patients, 36.9%), 3 segments (41 patients, 8.5%), 4 segments (18 patients, 3.7%). The average fusion segment length was 1.65 segments. The most commonly treated levels were L4-5 and L3-4. Complications were encountered in 81 patients (16.7%). In group 1, complications occurred in 35 patients (20.1%), and in group 2, complications occurred in 51 patients (14.8%).

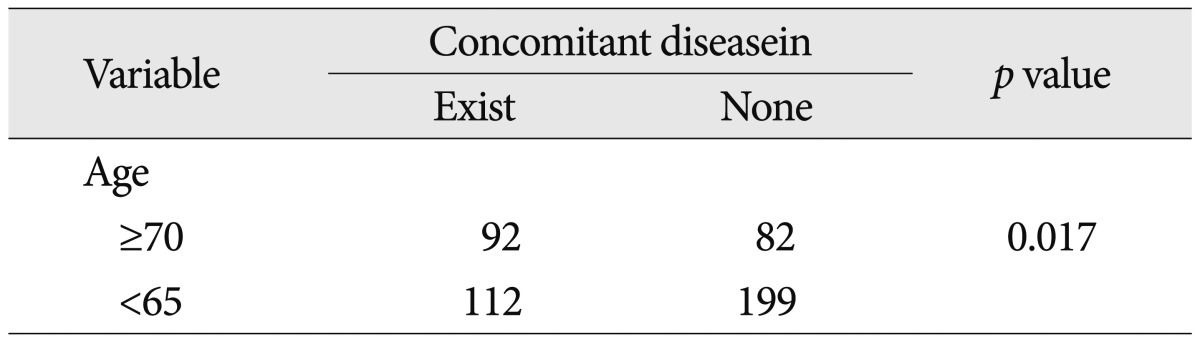

Among the observed comorbidities, the most common problem was hypertension, which was present preoperatively in 81 patients (39.7%). Other comorbidities were cardiovascular diseases (32 patients, 15.7%), renal diseases (29 patients, 14.2%), pulmonary diseases (36 patients, 17.6%), endocrine disease (75 patients, 36.8%), and hepatic diseases (20 patients, 9.8%). In addition, 47 patients (23.0%) had more than one comorbidity (Table 2). We also estimated the correlation between age and underlying disease. Underlying diseases were accompanied in 52.9% of the geriatric patients and there was a statistically significant association between age and underlying disease (p=0.017) (Table 3).

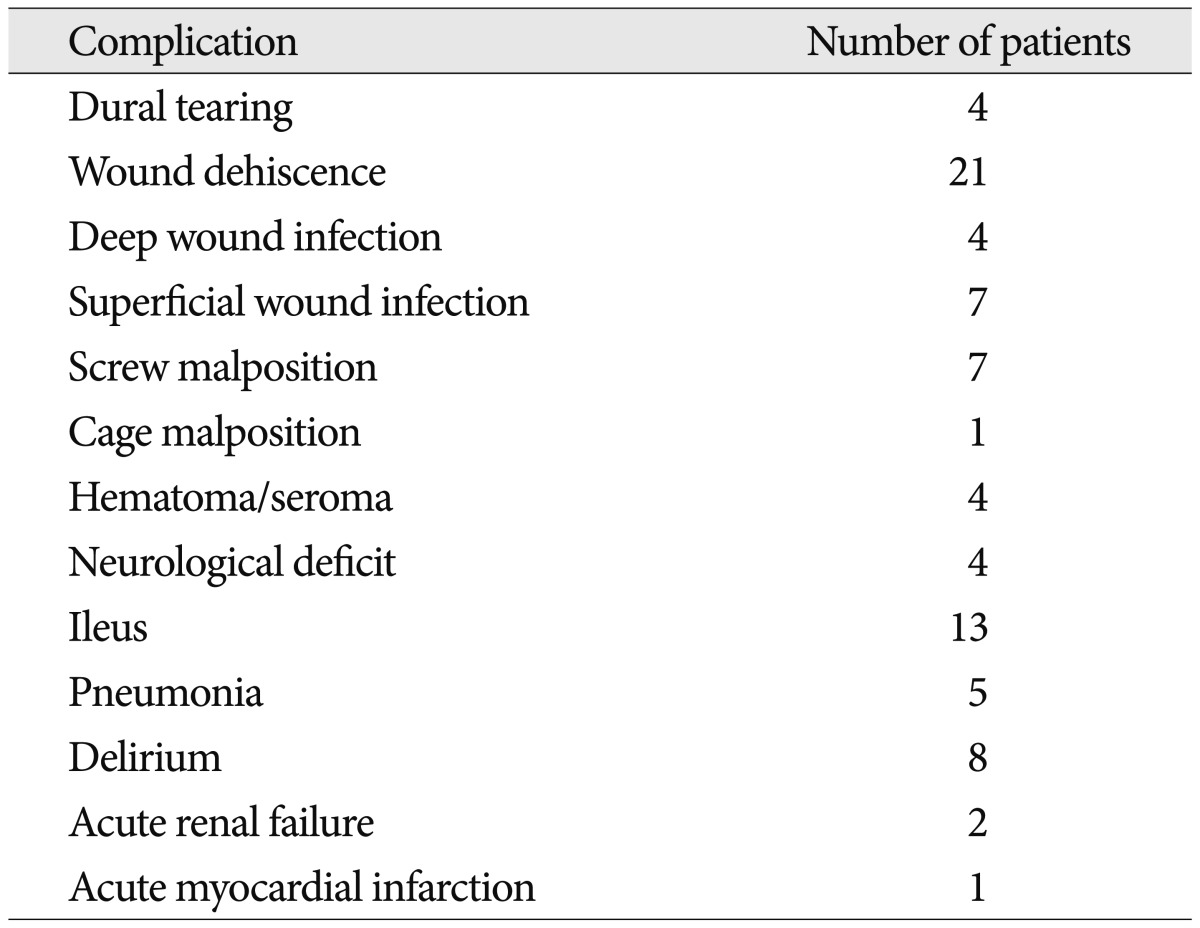

Complications arising in the 81 patients are organized in Table 4. The total peri-operative complication rate in all patients was 16.7%; the peri-operative complication rate in age group 1 was 20.1%, while the complication rate in group 2 was 14.8%. The most common complication was wound dehiscence (25.9%), and the second most prevalent was ileus, found in 16.0% of cases. Twenty-six of all complications required re-operation (3 cases of dura tearing, 10 cases of wound dehiscence, 2 cases of hematoma accumulation, 4 cases of superficial wound infection, 2 cases of deep wound infection, and 5 cases of screw malposition). All, except one patient, overcame the complications with proper treatment. The patient who presented with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) had a cardiac arrest on the third day after the surgery and died.

The results of the logistic regression analysis are in Table 5, displaying results of univariate and multivariate analysis in order of age, sex, comorbidity, ASA class, and fusion segment. Age was the only statistically significantly factor in both univariate and multivariate analyses (p=0.015 and 0.024). No correlation was found to be statistically significant between complications and sex, comorbidity, ASA class, fusion segment (p>0.05).

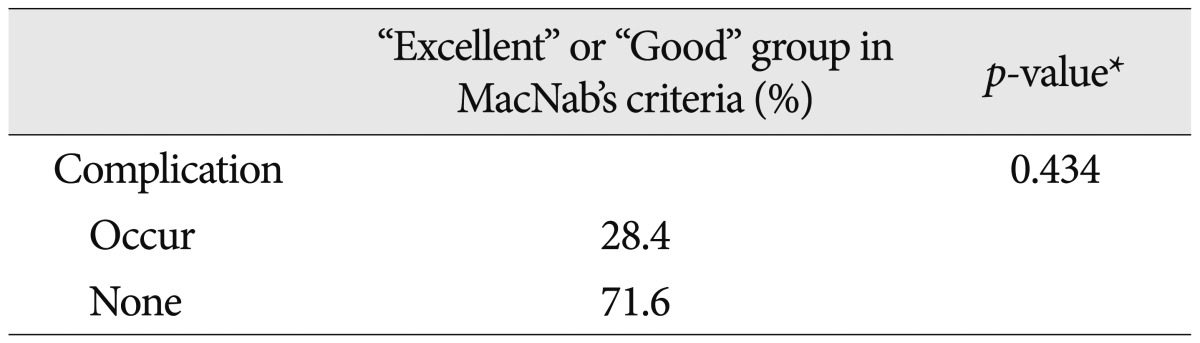

Based on the mean MacNab's criteria, post-operative outcome of 485 patients revealed as "excellent" in 280 patients (57.7%), "good" in 132 patients (27.2%), "fair" in 57 patients (11.8%), and "poor" in 16 patients (3.3%). For those patients who showed "excellent" or "good" results, patients had satisfactory improvements. On the other hand, "fair" or "poor" outcomes occurred in 73 patients (15.1%). Patients in both age groups showed comparable post-operative outcomes; 143 (82.2%) patients in age group 1, and 308 (86.5%) patients in age group 2 showed "excellent" or "good" results.

Based on Fisher's exact test, which was done to find the correlation between occurrence of perioperative complications and post-operative outcome, there was no statistically significant relationship between perioperative complications and "excellent" or "good" group in MacNab's criteria (Table 6).

Go to :

The number of elderly persons in the Republic of Korea continues to grow; by 2050, 38.2% of the population is expected to be older than 65 years, greatly exceeding the worldwide mean of 16.2%. An aging population will consequently suffer from age-related degenerative diseases, such as disorders of the spine. Advances in anesthesiology, spinal instrumentation, and postoperative care have made spinal procedures safer, with a decrease in morbidity and mortality, as well as continued improvements in patient outcomes6). Recognizing predictors of complications or poor outcome for the geriatric population is crucial for perioperative risk assessment and applying appropriate preventative procedures. If symptoms of degenerative spinal diseases persist after conservative treatments, surgical treatments may be considered5,9,15).

Similar to several previous retrospective studies, the complication rate in this analysis was 16.7%2,8). In a review of 105 spine surgery articles, Nasser et al.22) reported an overall pooled complication incidence of 16.4%. At 2.6% incidence rate, the most common perioperative complication observed in this study was wound dehiscence. Re-operation after a spinal fusion surgery may be considered a failure of the initial surgery by the patient and the surgeon. It also represents an additional procedure in patients who are already at significant risk for complication6). Mok et al.21) recently evaluated the need for revision surgery in patients undergoing adult spine surgery, finding a cumulative rate of 25.8%, while Cloyd et al.6) reported a re-operation rate of 27.4% in patients at least 65 years old who presented with a wide range of spine pathologies. Recently, Lee et al.20) reported that the rate of revision surgery due to complications was approximately 47%. In our study, the rate of revision surgery due to complications was approximately 40.6%, but age was not associated with the need for re-operation.

Okuda et al.23) found that patients older than 70 years who underwent posterior lumbar interbody fusions for spondylolisthesis had a complication rate of 16%, which was not significantly different from that in younger patients. Kilinçer et al.18) agreed that age did not affect the complication rates of posterior lumbar interbody fusion, but they did not report a complication rate separately for older patients. Vitaz et al.33) suggested that elderly patients with lumbar spinal diseases can be surgically treated in the same manner as the younger patients.

On the other hand, Deyo et al.8) researched retrospective analysis of a statewide hospital discharge registry, in which more than 18000 hospitalization data were complied over a two-year period, excluding patients with nondegenerative pathologies, authors reported an overall complication rate of only 10.3% for the surgical treatment of degenerative lumbar spine disease, although the rate for patients older than 75 years was higher (18%). In a different study, Cloyd et al.6) indicated an alarming 24.2% of elderly patients presented a major postoperative complications, and 53.2% showed at least one in-hospital complication; the authors found that age was a risk factor for major postoperative complications. Recently, Lee et al.20) retrospectively investigated 489 patients with various lumbar spinal diseases who had lumbar spinal fusion surgeries and showed a difference between the older (70 years and older) and younger patients (under 65 years old); the complication rate of the older group was 9%, while that of the younger group was 6%. However, in this study, medical complications were excluded. Our data further supports the statistically significant difference in peri-operative complication rate between the older and young groups; the complication rate of the older group was 20.8%, while that of the younger group was 14.8% (univariate analysis, p=0.015; multivariate analysis, p=0.024).

The mortality rate of 0.6% in the elderly group studied by Deyo et al.8) was approximately three times greater than the rates commonly cited for lumbar diskectomy. Silvers et al.31) reported a mortality rate of 0.8% for mortalities that occurred 1 to 2 months after the surgeries. In our study, one patient (0.2%) died three days after the surgery due to an AMI (Table 4). The deceased patient had AMI history as a comorbidity. The operation was performed on Level 1 (L4-5), and duration was 196 minutes. The blood loss was 350 cc, comparatively less than the mean blood loss, and a transfusion was not necessary. There were no variances during or post operation in the status of the patient. This study's mortality rate of 0.2% is lower than other reported rates.

The relationship between comorbidities and surgical outcome has been historically controversial. Early studies examining the effect of age on decompression with fusion for lumbar stenosis affirmed that the multiple comorbidities were associated with perioperative complications17,25,30). Katz et al.18) reported that cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and other comorbidities led to poorer scores in most of the outcome measurements. However, for lumbar spinal fusion surgeries in the elderly, several recent studies have found the opposite to be true1-4,18). In the study by Lee et al.20), perioperative complications were not significantly associated with comorbidities. The results of our study indicated that for lumbar spinal fusion surgeries, presence of comorbidities was not associated with perioperative complications (univariate analysis, p=0.132; multivariate analysis, p=0.325). Also, our study revealed that ASA classifications were not statistically significant (univariate analysis, p=0.376; multivariate analysis, p=0.513).

Elderly patients who are diagnosed with symptomatic spinal pathology may require single or expansive lumbar fusions to ensure adequate fusion and inhibit future instrumentation-related complications6). Several studies have proposed that longer fusion lengths may lead to an increased risk of complications in the elderly3,4,27). Carreon et al.3) found an OR of 2.4 for postoperative complications in older patients undergoing lumbar arthrodesis with instrumentation. Similarly, Cassinelli et al.4) reported that fusion of four or more segments was a predictor of complications. The mean number of levels fused in these studies was 2.4 and 1.9, respectively. On the other hand, Daubs et al.7) studied patients 60 years and older who underwent spinal arthrodesis with a mean of 9.1 levels fused and found no association between the length of fusion and complication risk. Moreover, Glassman et al.10) advised that extending the fusion length may actually improve clinical outcomes in correcting poor sagittal balance or spinal cord compression. In our study, there was no significant association between the number of segments fused and the risk of perioperative complications in patients of all ages, including the elderly (univariate analysis, p=0.297; multivariate analysis, p=0.446).

Our last followed outcome based on MacNab's criteria concluded that 412 (85.0%) out of 485 people had excellent or good results since they have resumed their daily activities with minimal, if any, pain. The results for MacNab's criteria in age group 1 (70 years and older) and 2 (younger than 65 years) were 82.2% and 86.5%, showing only a small difference. These results are comparable with those in other reports of favorable outcomes, not only in the elderly, but in patients younger than 70 years as well. Lee et al.19), reported a study with 30 patients who underwent PLIF (mean age 53.53±6.6). The analysis of MacNab's criteria results showed 10% as "excellent" and 66.7% as "good". In a similar study by Sakeb and Ahsan28), a total of 52 cases (11 men and 41 women, mean age 46 years SD 05.88, range 40-59 years) were analyzed on the outcome one year after PLIF surgeries. The reported MacNab's criteria results were 55.77% "excellent" and 38.46% "good". Hur et al.14) examined 20 patients (mean age 70 years) who underwent laminectomy and fusion. The MacNab's criteria analysis at 6 months after operation had outcomes of 7% "excellent" and 86% "good". Sanderson and Wood29) indicated excellent or good results in 81% of their patients 65 years of age or older during an average follow-up period of 42 months. Silvers et al.31) reported that 93% of the patients in their study (average age, 65 years) had relief of pain, and that 5% returned to activity in the short-term outcome analysis. Herkowitz and Kurz12) also reported a 96% rate of excellent or good results during an average follow-up period of 3 years for patients with a mean age of 65 years (range, 30-87 years) who received decompression and arthrodesis for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Johnsson et al.16) agreed with excellent or good results in approximately 60% of the patients in their study with a mean age 61.3 years (range, 48-80 years). Postacchini et al.26) reported excellent or good results for 67% of the patients during an average period of 8 years (range, 4-21 years). Lastly, Hall et al.11) reported excellent or good results during a mean follow-up period of 4 years in 84% of patients, whose mean age was 63 years (range, 32-83 years).

While the findings of the current study are important, there are several limitations. First, as this is a retrospective analysis, for which the limitations are well known, results may underestimate the actual complication incidence. It is common in retrospective studies for investigator recall bias to be introduced, whereby the accuracy of medical records may lead to falsely low reported rates of complication13). Second, there are opportunities for several other biases. Given the significant complexity of the patient population, the current study population may not represent the spine surgery population as a whole. Therefore, these findings may not be applicable to the general spinal fusion surgery patients.

Go to :

Increasing age was an important risk factor for perioperative complications in patients undergoing lumbar spinal fusion surgery, whereas other factors were not significant. However, patients' satisfaction or return to daily activities when compared with younger patients does not show much difference. We recommend good clinical judgment as well as careful selection of geriatric patients for lumbar spinal fusion surgery.

Go to :

References

1. Benz RJ, Ibrahim ZG, Afshar P, Garfin SR. Predicting complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001; 116–121. PMID: 11249156.

2. Boakye M, Patil CG, Ho C, Lad SP. Cervical corpectomy : complications and outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2008; 63:295–301. discussion 301-302. PMID: 18981834.

3. Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR 2nd, Glassman SD, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85:2089–2092. PMID: 14630835.

4. Cassinelli EH, Eubanks J, Vogt M, Furey C, Yoo J, Bohlman HH. Risk factors for the development of perioperative complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression and arthrodesis for spinal stenosis : an analysis of 166 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007; 32:230–235. PMID: 17224819.

5. Cho JM, Yoon SH, Park HC, Park HS, Kim EY, Ha Y. Surgery of spinal stenosis in elderly patients-bilateral canal widening through unilateral approach. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2004; 35:492–497.

6. Cloyd JM, Acosta FL Jr, Cloyd C, Ames CP. Effects of age on perioperative complications of extensive multilevel thoracolumbar spinal fusion surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010; 12:402–408. PMID: 20367376.

7. Daubs MD, Lenke LG, Cheh G, Stobbs G, Bridwell KH. Adult spinal deformity surgery : complications and outcomes in patients over age 60. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007; 32:2238–2244. PMID: 17873817.

8. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Loeser JD, Bigos SJ, Ciol MA. Morbidity and mortality in association with operations on the lumbar spine. The influence of age, diagnosis, and procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992; 74:536–543. PMID: 1583048.

9. Fast A, Robin GC, Floman Y. Surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis in the elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985; 66:149–151. PMID: 3977565.

10. Glassman SD, Berven S, Bridwell K, Horton W, Dimar JR. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005; 30:682–688. PMID: 15770185.

11. Hall S, Bartleson JD, Onofrio BM. Lumbar spinal stenosis : Clinical features, diagnostic procedures, and results of surgical treatment in 68 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1985; 103:271–275. PMID: 3160275.

12. Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis : A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991; 73:802–808. PMID: 2071615.

13. Hess DR. Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care. 2004; 49:1171–1174. PMID: 15447798.

14. Hur JW, Kim SH, Lee JW, Lee HK. Clinical Analysis of Postoperative Outcome in Elderly Patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2007; 41:157–160.

15. Ji YC, Kim YB, Hwang SN, Park SW, Kwon JT, Min BK. Efficacy of unilateral laminectomy for bilateral decompression in elderly lumbar spinal stenosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2005; 37:410–415.

16. Johnsson KE, Willner S, Pettersson H. Analysis of operated cases with lumbar spinal stenosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981; 52:427–433. PMID: 7315234.

17. Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, McInnes JM, Fossel AH, Liang MH. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991; 73:809–816. PMID: 2071616.

18. Kilinçer C, Steinmetz MP, Sohn MJ, Benzel EC, Bingaman W. Effects of age on the perioperative characteristics and short-term outcome of posterior lumbar fusion surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005; 3:34–39. PMID: 16122020.

19. Lee JH, Chun HJ, Yi HJ, Bak KH, Ko Y, Lee YK. Perioperative risk factors related to lumbar spine fusion surgery in Korean geriatric patients. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2012; 51:350–358. PMID: 22949964.

20. Lee SH, Chung BJ, Lee HY, Shin SW. A comparison between interspinous ligamentoplasty, posterior interbody fusion, and posterolateral fusion in the treatment of grade I degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi. 2005; 16:111–117.

21. Mok JM, Cloyd JM, Bradford DS, Hu SS, Deviren V, Smith JA, et al. Reoperation after primary fusion for adult spinal deformity : rate, reason, and timing. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009; 34:832–839. PMID: 19365253.

22. Nasser R, Yadla S, Maltenfort MG, Harrop JS, Anderson DG, Vaccaro AR, et al. Complications in spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010; 13:144–157. PMID: 20672949.

23. Okuda S, Oda T, Miyauchi A, Haku T, Yamamoto T, Iwasaki M. Surgical outcomes of posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006; 88:2714–2720. PMID: 17142422.

24. Okuda S, Oda T, Miyauchi A, Haku T, Yamamoto T, Iwasaki M. Surgical outcomes of posterior lumbar interbody fusion in elderly patients. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007; 89(Pt. 2):Suppl 2. 310–320. PMID: 17768224.

25. Oldridge NB, Yuan Z, Stoll JE, Rimm AR. Lumbar spine surgery and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries, 1986. Am J Public Health. 1994; 84:1292–1298. PMID: 8059888.

26. Postacchini F, Cinotti G, Gumina S. Long-term results of surgery in lumbar stenosis : 8-year review of 64 patients. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1993; 251:78–80. PMID: 8451996.

27. Raffo CS, Lauerman WC. Predicting morbidity and mortality of lumbar spine arthrodesis in patients in their ninth decade. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006; 31:99–103. PMID: 16395185.

28. Sakeb N, Ahsan K. Comparison of the early results of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and posterior lumbar interbody fusion in symptomatic lumbar instability. Indian J Orthop. 2013; 47:255–263. PMID: 23798756.

29. Sanderson PL, Wood PL. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenisis in old people. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993; 75:393–397. PMID: 8496206.

30. Sidhu KS, Herkowitz HN. Spinal instrumentation in the management of degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997; 39–53. PMID: 9020205.

31. Silvers HR, Lewis PJ, Asch HL. Decompressive lumbar laminectomy for spinal stenosis. J Neurosurg. 1993; 78:695–701. PMID: 8468598.

32. Tadokoro K, Miyamoto H, Sumi M, Shimomura T. The prognosis of conservative treatments for lumbar spinal stenosis : analysis of patients over 70 years of age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005; 30:2458–2463. PMID: 16261126.

33. Vitaz TW, Raque GH, Shields CB, Glassman SD. Surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis in patients older than 75 years of age. J Neurosurg. 1999; 91:181–185. PMID: 10505502.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download