Abstract

Occipital neuralgia is a rare pain syndrome characterized by periodic lancinating pain involving the occipital nerve complex. We present a unique case of entrapment of the greater occipital nerve (GON) within the semispinalis capitis, which was thought to be the cause of occipital neuralgia. A 66-year-old woman with refractory left occipital neuralgia revealed an abnormally low-loop of the left posterior inferior cerebellar artery on the magnetic resonance imaging, suggesting possible vascular compression of the upper cervical roots. During exploration, however, the GON was found to be entrapped at the perforation site of the semispinalis capitis. There was no other compression of the GON or of C1 and C2 dorsal roots in their intracranial course. Postoperatively, the patient experienced almost complete relief of typical neuralgic pain. Although occipital neuralgia has been reported to occur by stretching of the GON by inferior oblique muscle or C1-C2 arthrosis, peripheral compression in the transmuscular course of the GON in the semispinalis capitis as a cause of refractory occipital neuralgia has not been reported and this should be considered when assessing surgical options for refractory occipital neuralgia.

Occipital neuralgia is an uncommon, specific syndrome of paroxysmal severe lightening-like sharp headache in the distribution of the greater or lesser occipital nerves (GON, LON). This paroxysmal jabbing pain may be associated with aching in the greater or LON distribution between the paroxysms of the pain. Often there is tenderness over the nerve and sometimes there can be diminished sensation or dysesthesia in the distribution of the nerve. The pain is temporarily relieved by local block8). Although most cases of occipital neuralgia are considered idiopathic, they may be related to specific causes such as trauma, prior skull base surgery, rheumatoid arthritis, nerve entrapment by hypertrophied atlantoepistrophic (C1-C2) ligaments, or compression by an anomalous ectatic vertebral artery4,5,7,9,12,13). Although occipital neuralgia has been reported to occur by peripheral compression of the GON along its course around the inferior oblique muscle6), occurrence of occipital neuralgia, not cervicogenic headache, by entrapment in the transmuscular course of the semispinalis capitis has not been reported.

We report a patient with intractable occipital neuralgia refractory to all forms of conservative treatment. The intraoperative findings were unique in that the GON was entrapped at the site of its perforation of the semispinalis capitis muscle. After neurolysis of the GON at the perforation site of the semispinalis capitis muscle, the previously intractable occipital pain was much alleviated.

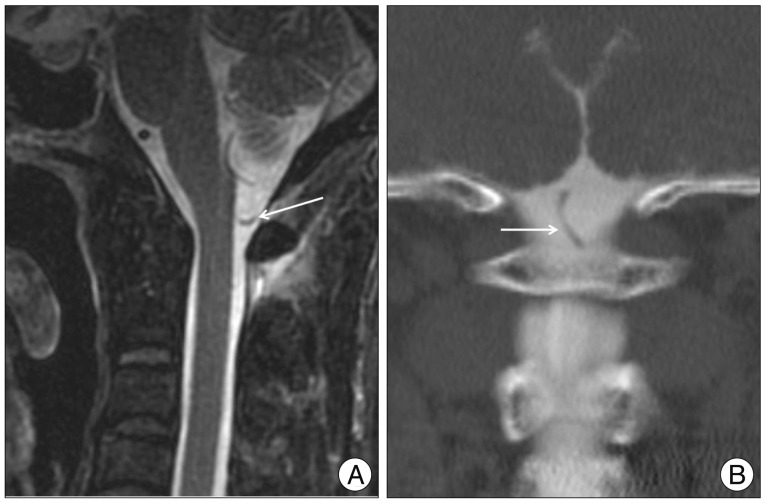

A 66-year-old, female developed episode of paroxysmal, severe lancinating pain in her left occipital region, correlating to the area of the GON. Mild pain had started 6 months before and had increased progressively in severity and frequency. The pain originated at the occipitocervical junction and radiated to the vertex. It was sharp, lancinating in nature and exacerbating factors such as neck flexion were not found. At times, it was associated with nausea and photosensitivity. Attacks of lancinating pain with a severity score of 9/10 on a visual analog scale (VAS) lasted for a few seconds. A residual dull aching pain remained between the attacks (score 5/10 on a VAS). The frequency of paroxysmal pain progressively increased and eventually became almost constant for 1 month until, she became bed-ridden without being able to do her daily activities. On examination, a painful, dysesthetic allodynia was present over the left GON distribution. During evaluation, she was placed on more than 7 medications that included non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiemetics, anticonvulsants including carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and gabapentin, β-blockers, anticholinergics, steroids, and triptans. Opioids including 40 mg of IRcodon and transdermal fentanyl patch were tried in vain. A block of the GON could provide transient relief of neuralgic pain for only about 1 hour. Radiofrequency ablation of the GON was tried with minimal effect. Intramuscular injection of diclofenac sodium could provide only 2-3 hours of partial relief. The flexion and extension views of the cervical spine showed no evidence of subluxation or arthritic change. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cervical spine was obtained and was negative for any mass lesion and upper cervical degenerative change. On the T2-weighted sequence, an anomalously low PICA loop was observed on the left. The distal loop extended to the level of the C1 lamina (Fig. 1A). To evaluate the possibility of the low-lying PICA loop compressing the upper cervical roots, a computed tomographic myelography was performed and showed the same finding of the MRI (Fig. 1B) : the left PICA was low so that it extended to the level of C1. A superficial vascular ultrasound with a 17 MHz linear transducer showed no abnormal vascular contact along the course of the GON.

Considering the intractability of the occipital neuralgia and the possible vascular compression of the upper cervical root, the explorations of the GON, the dorsal rami of the C2 root, and intradural C2 root were planned. A linear midline incision was made and the dissection was carried down along the course of the GON. Upon entering the semispinalis perforation of the semispinalis caipits, tight constriction and entrapment of the GON was noted (Fig. 2A). Careful dissection was performed to leave a generous amount of space surrounding the entrapment site to prevent postoperative constriction. There was no compression upon dissection of the proximal course of the GON around the inferior oblique muscle and the proximal dorsal rami of the C2 lateral to the foramen (Fig. 2B). After left-sided hemilaminotomy of C1 and dural opening, the low-lying PICA loop was not found to be in contact with the left side of the C2 posterior root (Fig. 2C). At the conclusion of the operation, the overlying wounds were closed avoiding any remnant constriction or compression along the course of the GON. Immediately upon awakening from the anesthesia, the patient was free of severe lancinating, neuralgic pain and experienced only the typical incisional pain of a surgical procedure. All medications including gabapentin, NSAIDs, and opioids were discontinued until postoperative three months. During 12 months' follow-up, she had no attack of lancinating pain of occipital neuralgia, although she experienced some paresthesia in her left occipital region. No hypesthesia and no allodynia were found at the follow-up.

Although most cases of occipital neuralgia are idiopathic, they may be related to specific causes. The specific causes of occipital neuralgia can be categorized into intradural and extradural peripheral causes. Among the intradural causes of occipital neuralgia, intramedullary etiologies are; bleeding from a bulbocervical cavernoma or cervicomedullary dural arteriovenous fistula, schwannoma of the cervicomedullary junction, and C2 myelitis7,9,12). The other intradural extramedullary etiologies were compression of the upper cervical roots by the structures in the vicinity such as ectatic vertebral artery and lower-lying PICA loop7,12). The extradural, peripheral causes were extrinsic compression or entrapment along the course of the C2 root and the GON, intrinsic lesions of the GON such as a schwannoma of the GON and metabolic disorders (diabetes, gout), and trauma to the occipital nerve such as occurs with whiplash injury and skull base surgery7). The peripheral extrinsic lesions causing occipital neuralgia were hypertrophied atlantoepistrophic (C1-C2) ligament, degenerative C1-C2 arthrosis, pathological occipital arterial contact with GON5,7,9,12). The diagnosis of occipital neuralgia should be distinguished from cervicogenic headache due to occipital referred pain from other sources, such as the atlantoaxial or upper zygoapophyseal joints13).

Occipital neuralgia may be refractory to medical treatment that typically includes analgesics such as NSAIDs, steroids, triptans, opioids, antiepileptics, and antidepressants. Occipital nerve block with or without corticosteroids, chemical or radiofrequency ablation, or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may be additional options. If conservative efforts fail, surgical treatment such as dorsal rhizotomy, release of nuchal muscles to entrap the nerves, occipital neurectomy, and microvascular decompression may be considered6,9,13).

In 1982, Bogduk1) performed the anatomic study of the cervical sensory nerves and the GON, which is the continuation of the medial branch of the C2 dorsal root. An important finding of this study was that the semispinalis muscle was the only site of consistent muscular investment of the GON. In 1991, Bovim et al.2) revisited the anatomic course of the GON, and contrary to Bogduk's earlier work, found three potential sources of muscular investment : the semispinalis (90%), the trapezius (45%), and the inferior oblique (7.5%). The GON has been described as piercing several muscles along its length, specifically the inferior oblique, the trapezius, and the semispinalis. Theoretically, any one (or combination) of these muscular investments could serve as a source of compression or irritation of the GON. However, Mosser et al.10) found in their anatomic study of the GON that the only consistent transmuscular course was in the region of the semispinalis and thought this course in the semispinalis muscle would be the most likely point of compression or irritation.

Our finding of constriction of the GON by the semispinalis is in line with the finding described by Mosser et al.11). However, they suggested this compression might be related to a peripheral mechanism involved in the etiology of migraine headaches and not in the etiology of occipital neuralgia3).

The report describing transmuscular neurolysis of the GON in true occipital neuralgia is rare6,10) and most of them reported application of neurolysis in cervicogenic headache3,10). Gille et al.6) reported favorable results of neurolysis of the GON through sectioning of the inferior oblique muscle in greater occipital neuralgia (favorable results in 7 out of 10 patients with GON neuralgia). However, their selection criteria stressed the finding of exacerbation or triggering of the pain by flexion of the cervical spine, thus indicating the pain involved stretching of the GON instead of irritation by compression. This selection criteria does not fit the diagnostic criteria of occipital neuralgia proposed by ICHD-II8). They sectioned the inferior oblique muscle for neurolysis of the GON and could not find any compression or entrapment of the semispinalis capitis in their 10 GON neuralgia patients6).

Neurolysis of the GON in its peripheral course in the nuchal musculature, especially in the trapezius insertion, has already been described by Bovim et al.3). However, their application of neurolysis was for the treatment of cervicogenic headache and not for typical occipital neuralgia3). In their diagnostic criteria for cervicogenic headache3), the effect of anesthetic blockade of the GON was an essential part3). However, according to current criteria of ICHD-II on headache classification8), temporary relief by local anesthetic block of a cervical structure or its nerve supply using placebo- or other adequate control is an important part in diagnosis of the cervicogenic headache and temporary pain relief by blockade of the GON is an essential part in diagnosis of occipital neuralgia. Thus, there seems to be a diagnostic uncertainty in previous reports dealing peripheral transmuscular neurolysis of the GON. Furthermore, in their procedure of the GON neurolysis3), liberation of the GON at the insertion of the trapezius muscle was the main goal, not complete decompression along the course of the GON. Only two patients were pain-free at the last follow-up, and almost all patients experienced recurrence with time.

Magnüsson et al.10) reported the results of 18 decompressions of the GON in 15 patients with occipital neuralgia following the whiplash injury, and they showed good or excellent results in 13 (72%) of 18 GON release. They explained their good results for their neurolysis along the course of the GON at the point of the semispinalis capitis in addition to the trapezius, and showed the importance of possible entrapment of the GON in the semispinalis capitis. However, they studied only for patients with occipital neuralgia developed after whiplash injury, not true idiopathic occipital neuralgia. Occipital neuralgia must be distinguished from occipital referral of pain from the atlantoaxial or upper zygapophyseal joints or from tender trigger points in neck muscles or their insertions8).

In the present case, the radiological examination suggested a close contact between the intradural C2 root and the low-lying PICA loop, which seemed to be a similar finding to a previous report of occipital neuralgia caused by vascular compression described by White et al.13). However, we could not find any vascular contact along the course of the GON and the cervical roots. Indeed, we only found the constriction of the GON in the transmuscular perforation of the semispinalis during the intraoperative dissection, a discovery which we did not expect.

The present case gave us an instruction that the entire structures along the course of the GON could be a source of occipital neuralgia, and we think that we need to pay more attention to possible, anatomical structures in the course of the GON in performing neurolysis of the GON in occipital neuralgia.

In our case of refractory occipital neuralgia, decompression and neurolysis in the transmuscular perforation site of the semispinalis capitis led to almost complete and long-term relief of the severe neuralgia pain of occipital neuralgia. We suggest that occipital neuralgia may on occasion be produced by entrapment of the GON in the perforation site of the semispinalis capitis. In medically-refractory occipital neuralgia, peripheral compression along the course of the GON should be also sought.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank to professor Takaomi Taira in Tokyo Women's Medical University for his thoughtful consideration and guidance in the operation of occipital neuralgia.

References

1. Bogduk N. The clinical anatomy of the cervical dorsal rami. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1982; 7:319–330. PMID: 7135065.

2. Bovim G, Bonamico L, Fredriksen TA, Lindboe CF, Stolt-Nielsen A, Sjaastad O. Topographic variations in the peripheral course of the greater occipital nerve : Autopsy study with clinical correlations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991; 16:475–478. PMID: 2047922.

3. Bovim G, Fredriksen TA, Stolt-Nielsen A, Sjaastad O. Neurolysis of the greater occipital nerve in cervicogenic headache. A follow up study. Headache. 1992; 32:175–179. PMID: 1582835.

4. Cornely C, Fisher M, Ingianni G, Isenmann S. Greater occipital nerve neuralgia caused by pathological arterial contact : treatment by surgical decompression. Headache. 2011; 51:609–612. PMID: 21457245.

5. Ehni G, Benner B. Occipital neuralgia and the C1-2 arthrosis syndrome. J Neurosurg. 1984; 61:961–965. PMID: 6491740.

6. Gille O, Lavignolle B, Vital JM. Surgical treatment of the greater occipital neuralgia by neurolysis of the greater occipital nerve and sectioning of the inferior oblique muscle. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004; 29:828–832. PMID: 15087807.

7. Hammond SR, Danta G. Occipital neuralgia. Clin Exp Neurol. 1978; 15:258–270. PMID: 756019.

8. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004; 24(Suppl 1):9–160. PMID: 14979299.

9. Kuhn WF, Kuhn SC, Gilberstadt H. Occipital neuralgias : Clinical recognition of a complicated headache. A case series and literature review. J Orofac Pain. 1997; 11:158–165. PMID: 10332322.

10. Magnússon T, Ragnarsseon T, Björnsson AO. Occipital nerve release in patients with whiplash trauma and occipital neuralgia. Headache. 1996; 36:32–36. PMID: 8666535.

11. Mosser SW, Guyuron B, Janis JE, Rohrich RJ. The anatomy of the greater occipital nerve : implications for the etiology of migraine headaches. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 113:693–697. PMID: 14758238.

12. Poletti CE, Sweet WH. Entrapment of the C2 root and ganglion by the atlantoepistrophic ligament: clinical syndrome and surgical anatomy. Neurosurgery. 1990; 27:288–291. PMID: 2385345.

13. White JB, Atkinson PP, Cloft HJ, Atkinson JLD. Vascular compression as a potential cause of occipital neuralgia : a case report. Cephalalgia. 2008; 28:78–82. PMID: 18021267.

Fig. 1

A : Sagittal, fast-spin echo T2-weighted magnetic resonance images of the occipito-cervical junction showing the anomalous course of the left posterior inferior cerebellar artery (arrow). B : Coronal, reformatted computed tomography-myelogram images of the occipito-cervical junction showing the tortuous and caudal course of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery as it closes the C1 lamina (arrow).

Fig. 2

A : Intraoperative photographs showing the constriction of the greater occipital nerve in its perforation site of the semispinaliscapitis muscle. B : A photograph showing no constriction along the peripheral course of the greater occipital nerve proximal to the semispinalis to the C2, 3 facet. C : An intraoperative photograph showing no vascular contact between the C1, 2 nerve roots and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download