Abstract

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a benign condition of non-neoplastic heterotopic bone formation in the muscle or soft tissue. Trauma plays a role in the development of MO, thus, non-traumatic MO is very rare. Although MO may occur anywhere in the body, it is rarely seen in the lumbosacral paravertebral muscle (PVM). Herein, we report a case of non-traumatic MO in the lumbosacral PVM. A 42-year-old man with no history of trauma was referred to our hospital for pain in the low back, left buttock, and left thigh. On physical examination, a slightly tender, hard, and fixed mass was palpated in the left lumbosacral PVM. Computed tomography showed a calcified mass within the left lumbosacral PVM. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed heterogeneous high signal intensity in T1- and T2-weighted image, and no enhancement of the mass was found in the postcontrast T1-weighted MRI. The lack of typical imaging features required an open biopsy, and MO was confirmed. MO should be considered in the differential diagnosis when the imaging findings show a mass involving PVM. When it is difficult to distinguish MO from soft tissue or bone malignancy by radiology, it is necessary to perform a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

Myositis ossificans (MO) is a benign, non-neoplastic, and heterotopic bone or cartilage formation in the muscle or soft tissue1,4,11). Although it can occur anywhere in the body, the lesions are localized predominantly in the high-risk sites of injury, such as the thigh, buttock, and elbow1,4). It is rarely seen in the paravertebral muscle (PVM)10,11). There is a certain role of trauma because 75% of cases are associated with it, thus, non-traumatic MO is rare11). To date, only a few cases of non-traumatic MO in the lumbosacral PVM have been reported. Sometimes, it is difficult to distinguish MO from soft tissue and bone malignancy by radiologic studies, and a biopsy is necessary to confirm the diagnosis4,11,12).

Herein, we present a case of non-traumatic MO in the lumbosacral PVM in a 42-year-old healthy male.

A 42-year-old man presented with a 4-month history of low back pain and pain in the left posterolateral part of the buttock and thigh. The patient appeared healthy and had no history of previous trauma or musculoskeletal disease. On physical examination, a slightly tender, hard, and fixed mass was palpated in the left PVM at the L5 level. Complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood chemistry values including serum calcium, phosphate, C-reactive protein, and alkaline phosphatase were all within normal limits.

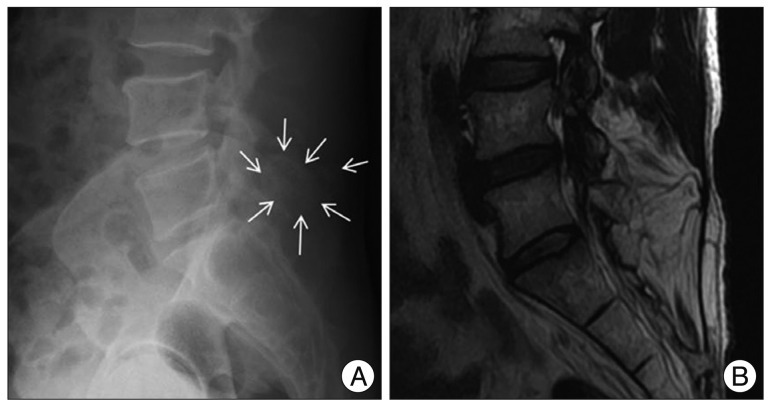

Lateral lumbosacral spine X-ray showed calcific density near the spinous process of L5 and S1 (Fig. 1A). T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed heterogeneous high signal intensity at the PVM from L5 to S2 (Fig. 1B). Axial MRI showed a heterogeneous high signal intensity mass in T1- and T2-weighted image in the left PVM, and no enhancement of the mass was found in the Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI (Fig. 2A, B, C). Findings on computed tomography revealed an inhomogenously calcified mass, and the mass was in continuity with or eroding the left-sided lamina, facet joint of the L5, and the sacrum (Fig. 2D).

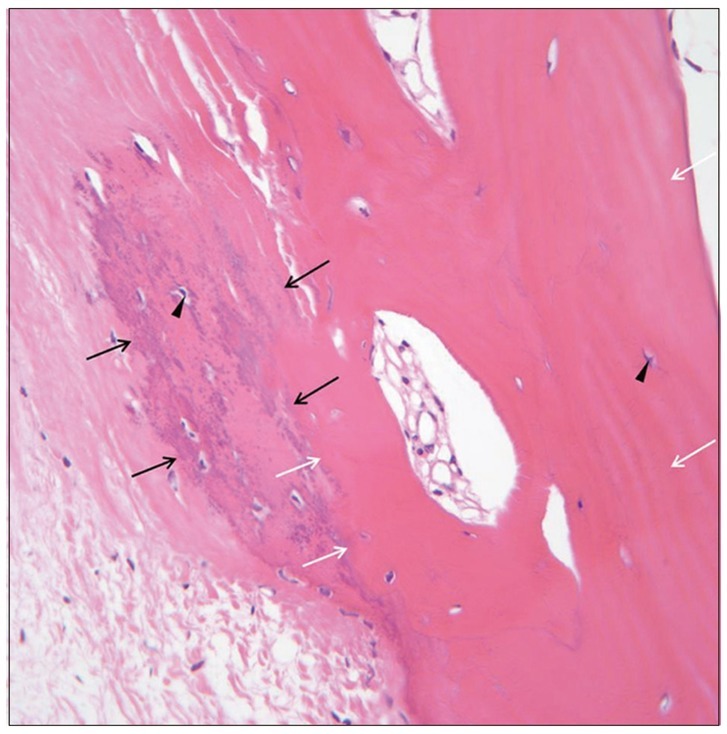

The lack of typical imaging features required an open biopsy, which showed no evidence of malignancy and confirmed MO (Fig. 3). The patient was followed up for 6 months after the biopsy and the patient's pain had been reduced gradually. However, a follow-up image could not be obtained, because of the patient's refusal due to financial difficulties.

Myositis ossificans is a localized, self-limiting ossifying process that follows mechanical trauma3). The cause of MO is thought to be posttraumatic inflammatory changes in skeletal muscle because 60-75% of patients describe a clear history of trauma1,3,4,8,10). However, trauma is not the only causative factor and the specific pathophysiological factors underlying the development of MO are not well-known at the present1,10). In cases with an apparent history of traumatic injury, it can be assumed that the process commences with tissue necrosis or hemorrhage followed by exuberant reparative fibroblastic and vascular proliferation with eventual ossification8). Several theories exist about the mechanism of MO. MO is a step in an organizing hematoma's development and it is caused by osteoblasts that have escaped from periosteum and migrated into soft tissue4). Mechanical injury can cause the osteoblast-containing periosteum to be pushed into muscle and thereby result in ectopic calcification in a muscle4). Another possible source of provocation includes organic diseases such as poliomyelitis, tabes, syringomyelia, paraplegia, tetanus and hemophilia1,4,10). In these entities, MO can always appear after trauma caused by passive movements9). In a small number of cases, the etiology includes burns, infections, and even drug abuse4,10).

Although it is rare, MO may arise spontaneously without antecedent trauma6,8,10-12). In non-traumatic MO, repetitive small mechanical injuries, ischemia, or inflammation have been implicated as possible causes of MO3,8). The present case seems to belong to the non-traumatic MO. In the present case, the patient did not recall any history of trauma, had no history of the physiotherapy, injection therapy, or acupuncture for his pain, and none of the above-mentioned predisposing factors or diseases were identified. However, the possibility cannot be excluded that a minor trauma has been overlooked or forgotten by the patient.

Myositis ossificans affecting the PVM is very rare except for fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP)1,2,7,11). FOP is an autosomal dominant disorder with an average age of onset at 5 years; the onset range is from birth to 25 years7). FOP may present its first symptom as a firm paravertebral swelling with a reddened overlying skin with no history of trauma11). It is a progressive disease, and malformed big toes or thumbs are common anomalies that appear with FOP7,11). In the present case, the patient was in his 40s, did not have any congenital anomalies, and had no family history of musculoskeletal disease, which lowered the possibility of FOP. As far as we know, only a few cases of MO involving the PVM have been reported, irrespective of the traumatic or non-traumatic cause1,2,6,10-12). MO affecting the lumbar PVM is rarer than that of the cervical PVM. However, the cause is uncertain, and we could not find any reports or hypotheses about this point in the literature.

Histologically, bone maturation occurs from the periphery to the center, and this zonal phenomenon of peripheral maturation is the most important diagnostic feature of MO6,8-10,12). In the central area, there are streams of cells producing collagen, in the intermediate area, there is an osteoblastic production of immature bone, and in the periphereal zone, the woven bone changes in mature lamellar bone12). Shortly after injury, a painful, tender, soft tissue mass becomes apparent, which may be associated with periosteal reaction in 7-10 days1). Flocculent dense lesions signifying the onset of ossification arise in the mass from 11 days to 6 weeks1,4,10). At 6-8 weeks, a lacy pattern of new bone with a sharp peripheral cortex is formed9). From 10 weeks to 6 months, the central zone may enlarge and produce the appearance of an "egg shell" at the end stage of maturation1,9). Full maturity is completed in 5-6 months, and then the mass usually begins to shrink1,4,9). After 1-2 years, most lesions regress and may even disappear1,4).

The appearance of MO on MRI is variable and depends on the maturity and the variation of the histological pattern within the lesion9,10). In the early stages, T2-weighted images may show an inhomogenous focal mass with high central signal intensity9,10). As the lesion matures and the peripheral ossification becomes denser, the images show a hyperintense center surrounded by a hypointense rim corresponding to peripheral ossification5,9,10). Chronic lesions are well-defined inhomogeneous masses with a signal intensity approximating that of fat, which may come from fatty marrow, on both T2- and T1-weighted images without associated edema, which was consistent with the present case5,9). However, in the present case, the lesion was in continuity with or eroding the adjacent left lamina, facet of L5, and the sacrum. Initially, a bone tumor arising from the lamina was suspected. It is the pathognomonic radiologic feature of traumatic MO that the lesion is not in continuity with the underlying bone2). This is important in distinguishing MO from osteosarcoma, osteochondroma, or osteobalstoma1,2). However, cases of traumatic MO that is in continuity with the adjacent cervical or lumbar vertebral body have been reported on as well1,4). In non-traumatic MO, the pathognomonic radiologic features have not been reported. However, the lesion was not in continuity with the adjacent bone in a few of the reported cases10,12).

Myositis ossificans is usually a self-limiting condition9). Because spontaneous regression can occur, most investigators are against surgical excision11). Conservative management with clinical and radiological follow-up may be sufficient when the lesion is typical9). Surgery is advised if the origin or insertion of muscle or tendon is involved, function is impaired, or the mass is unusually large or painful2,9,12). It is advisable to remove the lesion when it is mature2). Radiation therapy can be used to reduce the size and accelerate the maturation of the lesion2). In the present case, no surgery or radiation therapy was advised as the patient was not experiencing severe pain without neurological deficit nor was he experiencing functional impairment. However, the patient did not recall any history of trauma, the mass was located in an unusual location for MO, and the mass was in continuity with or eroding the underlying bone. Therefore, our clinical diagnosis was uncertain, and this led us to confirmation with a biopsy.

The occurrence of non-traumatic MO in the lumbosacral PVM is very rare. However, MO should be considered in the differential diagnosis when the imaging findings show a mass involving the PVM. When it is difficult to distinguish MO from soft tissue or bone malignancy by radiographic studies, it is necessary to perform a biopsy in order to confirm the diagnosis.

References

1. Baysal T, Baysal O, Sarac K, Elmali N, Kutlu R, Ersoy Y. Cervical myositis ossificans traumatica : a rare location. Eur Radiol. 1999; 9:662–664. PMID: 10354880.

2. Findlay I, Lakkireddi PR, Gangone R, Marsh G. A case of myositis ossificans in the upper cervical spine of a young child. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010; 35:E1525–E1528. PMID: 21102285.

3. Hatano H, Morita T, Kobayashi H, Ito T, Segawa H. MR imaging findings of an unusual case of myositis ossificans presenting as a progressive mass with features of fluid-fluid level. J Orthop Sci. 2004; 9:399–403. PMID: 15278779.

4. Kim SW, Choi JH. Myositis ossificans in psoas muscle after lumbar spine fracture. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009; 34:E367–E370. PMID: 19404167.

5. Kransdorf MJ, Meis JM, Jelinek JS. Myositis ossificans : MR appearance with radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991; 157:1243–1248. PMID: 1950874.

6. Mann SS, Som PM, Gumprecht JP. The difficulties of diagnosing myositis ossificans circumscripta in the paraspinal muscles of a human immunodeficiency virus-positive man : magnetic resonance imaging and temporal computed tomographic findings. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000; 126:785–788. PMID: 10864118.

7. Merchant R, Sainani NI, Lawande MA, Pungavkar SA, Patkar DP, Walawalkar A. Pre- and post-therapy MR imaging in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Pediatr Radiol. 2006; 36:1108–1111. PMID: 16932921.

8. Nishio J, Nabeshima K, Iwasaki H, Naito M. Non-traumatic myositis ossificans mimicking a malignant neoplasm in an 83-year-old woman : a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010; 4:270. PMID: 20704714.

9. Parikh J, Hyare H, Saifuddin A. The imaging features of post-traumatic myositis ossificans, with emphasis on MRI. Clin Radiol. 2002; 57:1058–1066. PMID: 12475528.

10. Saussez S, Blaivie C, Lemort M, Chantrain G. Non-traumatic myositis ossificans in the paraspinal muscles. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006; 263:331–335. PMID: 16133463.

11. Yazici M, Etensel B, Gürsoy MH, Aydoğdu A, Erkuş M. Nontraumatic myositis ossificans with an unusual location : case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2002; 37:1621–1622. PMID: 12407551.

Fig. 1

Lateral X-ray and T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbosacral spine. A : Lateral lumbosacral spine X-ray shows calcific density near the spinous process of L5 and S1 (white arrows). B : T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging shows heterogeneous high signal intensity at the paravetebral muscle from L5 to S2.

Fig. 2

Axial magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography of the lumbosacral spine. A and B : T2- (A) and T1-weighted axial magnetic (B) resonance imaging shows a heterogeneous high signal intensity mass in the left paravetebral muscle. Neither edema nor low signal intensity in the surrounding tissue are found. C : T1-weghted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging shows no enhancement of the mass. D : Computed tomography reveals an inhomogenously calcified mass, and the periphery of the mass is more calcified. The mass is in continuity with the left-side lamina, facet joint of the L5, and the sacrum.

Fig. 3

Histopathologic study. Pathologic specimen shows osteocartilagenous tissue in the fibrous tissue and no malignant cell is found. A transition from immature woven bone (black arrows) to mature lamellar bone (white arrows) is present and normal osteocytes (arrow heads) are seen (Hematoxylin & Eosin stain, ×400).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download