Abstract

Diagnosis of cerebral syphilitic gumma is frequently determined at the time of surgery, because imaging and laboratory findings demonstrate the elusive results. A 59-year-old woman presenting dysarthria showed a mass on her brain computed tomography. She was first suspected of brain tumor, but histological results from surgical resection revealed cerebral gumma due to neurosyphilis. After operation, she presented fever and rash with an infiltration on a chest X-ray. Histological assessment of skin was consistent with syphilis. Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed test IgG in cerebrospinal fluid was positive. She was successfully treated with ceftriaxone for 14 days.

Syphilis is a complex systemic illness with protean clinical manifestations caused by a spirochete, Treponema pallidum. The clinical course of syphilis is classically divided into the following phases : incubation period, primary syphilis, secondary syphilis, latent syphilis, and tertiary syphilis. During tertiary syphilis, relapse of secondary syphilis in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative person can occur up to four years after contact.

The central nervous system (CNS) may be involved at any stage of syphilis infection in about 5% to 10% of untreated patients10). CNS involvement in syphilis patients is classified into four syndromes : syphilitic meningitis, meningovascular syphilis, and parenchymatous and gummatous neurosyphilis. Differentiation from a brain mass in HIV-negative patients with syphilis is a challenge to clinicians1,7,12,18,22). Herein, we report an unusual case of cerebral syphilitic gumma mimicking a brain tumor with the relapse of secondary syphilis in a HIV-negative patient that was successfully controlled by administration of ceftriaxone.

A 59-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department with a 20-day history of speech disturbance. She had a medical history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, controlled well with medication at a local clinic.

Vital signs at admission were stable. She was alert but had cognitive disturbance (Glasgow Coma Scale 15 and Mini-Mental Status Examination 16/30) and dysarthria. Both pupils showed normal light reflex. There were no abnormal neurological findings for muscle strength and deep tendon reflexes in the extremities.

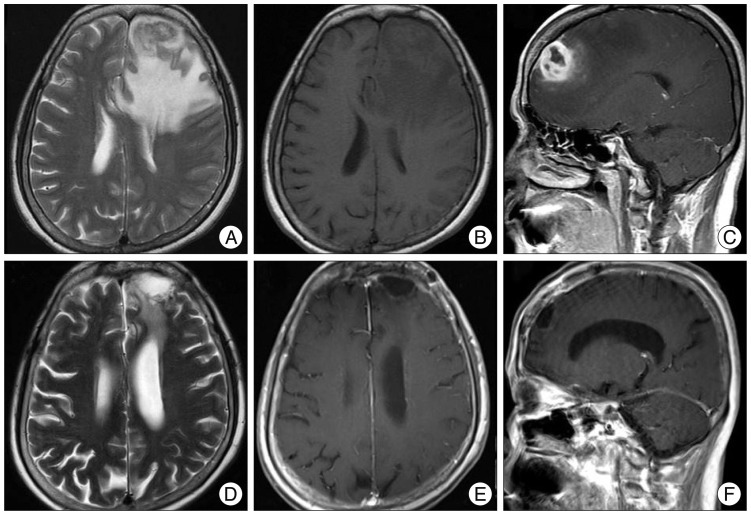

Computed tomography (CT) scanning of the brain revealed a mass-like lesion at the left frontal lobe and severe cerebral swelling. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an irregular enhancing mass with central necrosis that measured 2.8×2.7×2.6 cm in size (Fig. 1A). There was severe cerebral edema around the enhancing mass (Fig. 1B). The mass was adjacent to the enhanced dura in the left frontal lobe (Fig. 1C).

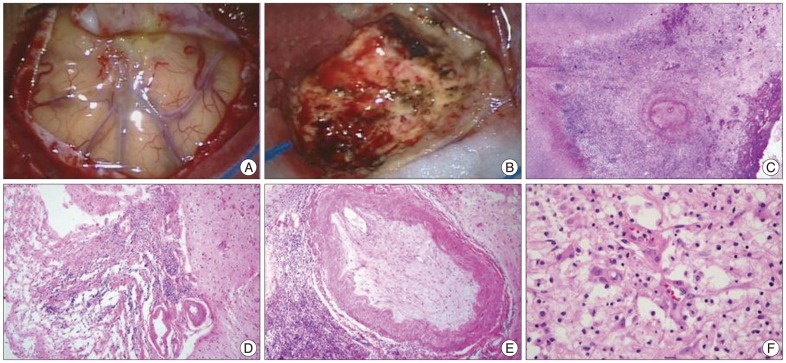

Malignant brain tumors including glioblastoma, metastatic brain tumor or primary CNS lymphoma were suspected with the need to rule out inflammatory conditions. To confirm the diagnosis, the mass was surgically resected with frontal craniotomy. On intraoperative findings, the mass was severely adhered to the dura. It was yellow in color and had a hard consistency (Fig. 2A, B). En bloc resection was performed and the intra-axial mass was completely removed. During the first admission, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was not performed, because lumbar puncture is contraindicated in the presence of increased intracranial pressure. On histopathological examination, the mass was first diagnosed as chronic inflammation originating from an unknown cause. Without any postoperative complications, she fully recovered from the cognitive defects and speech disturbance. She was discharged from the hospital 14 days after operation.

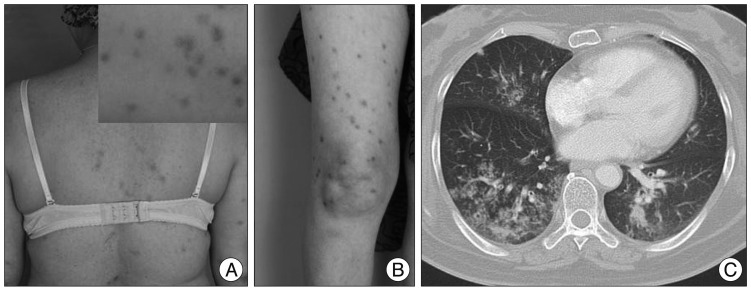

However, she was readmitted for high fever to the Department of Infectious Diseases 2 months after discharge. She had experienced non-itchy erythematous papules and macules over her whole body for three days (Fig. 3A, B). She had a history of sex with a partner who had multiple sex partners two years prior. She had an episode of primary syphilis at that time which was spontaneously resolved without any treatment. On admission, her initial vital signs were a body temperature of 39.5℃, blood pressure of 100/70 mm Hg, pulse rate of 91 beats/minute and respiratory rate of 22 times/minute. Physical examination revealed no generalized lymphadenopathy. On follow-up brain MRI, there was no enhancing mass lesion or severe edema at the cerebral parenchyma (Fig. 1D-F). Chest CT scans revealed an infiltration with interstitial pattern on the right lower lobe of the lung without respiratory symptoms (Fig. 3C). Results of a complete set of blood tests were as follows : white blood cell (WBC) count, 8200/µL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 42/mm3, and C-reactive protein, 187 mg/dL. Repeated blood and sputum cultures were negative. Serum mycoplasma antibody testing, including a follow-up test, were also negative. At that time, her serum Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) titer was 1 : 16, and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS) test IgM and IgG were reactive. Histopathological examination of the skin tissue revealed heavy lymphoplasmacytic infiltration consistent with lymphomatoid papulosis. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid yielded the following findings : 0 white cells/dL, 1 erythrocyte/mm2, glucose level of 74 mg/dL, protein level of 16.8 mg/dL, negative VDRL test, and negative T. pallidum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. However, FTA-ABS IgG in the CSF was reactive. Cardiovascular involvement was not noted with chest CT scans and transthoracic echocardiography. Ophthalmic fundoscopic examination also revealed no abnormal findings. Histopathological reassessment of the previous brain tissue revealed intraluminal obliteration of a large blood vessel just below the meninges, suggesting endarteritis (Fig. 2C). Spirochetes were not identified in this tissue by Warthin-Starry stain. Necrotic tissue in the neighboring brain parenchyma was also seen (Fig. 2D). Around the occluded vessel, parenchymal infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells was found (Fig. 2E, F). Other immunohistochemical examinations were negative for the possibility of malignant lymphoma, glioma and inflammatory pseudotumor.

The patient was finally diagnosed with cerebral gumma accompanied by probable pulmonary involvement in tertiary syphilis concomitant with relapse of secondary syphilis, on the evidence of the histopathological findings and positive FTA-ABS IgG in the serum and the CSF. Based on this diagnosis, ceftriaxone was intravenously administrated at a daily dose of 2 g for 14 days. Thereafter, the fever and rash subsided in two days, and an infiltration with interstitial pattern on subsequent chest X-ray showed marked improvement in three days. On April 9, 2012, her follow-up VDRL titer was 1 : 4. Her symptoms associated with syphilis fully resolved without relapse and she was doing well fifteen months after hospital discharge.

This is a rare case of cerebral syphilitic gumma with relapse of secondary syphilis in a HIV-negative patient that was successfully controlled by administration of ceftriaxone. Since she had not been treated for primary syphilis two years prior, clinical manifestations of tertiary syphilis presented as neurosyphilis and probable lung involvement.

Neurosyphilis can occur 1 to 25 years following syphilis infection and has various clinical manifestations4). Cerebral syphilitic gumma, first described by Botalli in 1563, is a rare manifestation, typically of tertiary syphilis17). As the present case illustrates, cerebral gummas typically arise from the dura and pia mater over the cerebral convexity or at the base of the brain and produce symptoms similar to those of other intracranial tumors1,7,12,13,18,22). Differential diagnosis for cerebral syphilitic gumma should be performed for other cerebral nervous system diseases including toxoplasmosis, lymphoma, bacterial and fungal infections. All of them are rare, but more common in HIV-positive patients compared with HIV-negative patients3). Syphilitic gumma has been described as a circumscribed mass of granulation tissue that results from localized inflammation as an excessive response of the cell-mediated immune system that manifests as the invasion of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Spirochetes seem to be rarely found in cerebral syphilitic gumma2,19). In the previous study, among the 156 cases with cerebral syphilitic gummas, T. pallidum was found on the histopathologic staining of only one case (0.6%)8). PCR for T. pallidum could be useful for definitive diagnosis in cases where diagnosis is difficult11). In our case, however, no spirochetes were observed on Warthin-Starry staining and her CSF was PCR-negative for T. pallidum, whereas VDRL titer was 1 : 16, and FTA-ABS test IgM and IgG were reactive. Therefore, we suggest that definitive diagnosis for cerebral syphilitic gumma should be examined serologic test for syphilis as well as histopathologic staining and PCR for T. pallidum.

At the time of presentation, our patient's CSF VDRL and pleocytosis were negative, while her serum nontreponemal test for syphilis and FTA-ABS in serum and CSF were positive. Routine laboratory CSF tests will fail to identify some patients with CNS invasion, as in our patient's case. A positive CSF VDRL test is highly specific for active neurosyphilis, but the test is negative in about half of neurosyphilis patients8,16). Even so, the serum VDRL test reportedly is negative in 30% to 50% of all cases with neurosyphilis21). Furthermore, a previous study reported that CSF pleocytosis, defined as >5 WBCs/µL in patients with neurosyphilis was seen in 40% of cases, regardless of the syphilis stage14). Finally, in HIV or non-HIV patients, a normal CSF does not exclude neurosyphilis.

The first choice treatment for tertiary syphilis is penicillin. There are very limited alternatives for the treatment of neurosyphilis. Ceftriaxone is a potential alternative to penicillin G for the treatment of neurosyphilis5,9,14,15,19,20). It is active against T. pallidum, penetrates CSF well, and has a long half-life that enables it to be given once daily. Our patient fully recovered from her symptoms associated with syphilis without relapse for seven months after the administration of ceftriaxone.

During the course of syphilis in our case, the relevance to syphilis of the lung parenchymal lesions was uncertain because the pathological examination was not confirmed. Acquired syphilis of the lung is a rare condition with variable diagnostic criteria6). However, in our patient, the diagnosis of probable pulmonary syphilis was made based on the fact that the radiologically-detected lesion disappeared under anti-syphilitic treatment for a very short period of time, in conjunction with the absence of respiratory symptoms and leukocytosis and the repeatedly negative sputum for tubercle bacilli or bacteria before antibiotic treatment.

In conclusion, this patient was treated with ceftriaxone after appropriate diagnosis through the surgical intervention, and completely recovered on follow-up at fifteen months. Our case report suggests that cerebral syphilitic gumma should be considered among HIV-negative patients with space-occupying lesions of the brain and tertiary syphilis, although the patient's CSF VDRL and pleocytosis were negative. Clinical suspicion and diagnosis of syphilitic gumma by physicians are vital.

References

1. Ances BM, Danish SF, Kolson DL, Judy KD, Liebeskind DS. Cerebral gumma mimicking glioblastoma multiforme. Neurocrit Care. 2005; 2:300–302. PMID: 16159080.

2. Berger JR, Waskin H, Pall L, Hensley G, Ihmedian I, Post MJ. Syphilitic cerebral gumma with HIV infection. Neurology. 1992; 42:1282–1287. PMID: 1620334.

3. Brightbill TC, Ihmeidan IH, Post MJ, Berger JR, Katz DA. Neurosyphilis in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients : neuroimaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995; 16:703–711. PMID: 7611026.

4. Clark EG, Danbolt N. The Oslo study of the natural history of untreated syphilis; an epidemiologic investigation based on a restudy of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material; a review and appraisal. J Chronic Dis. 1955; 2:311–344. PMID: 13252075.

5. Cnossen WM, Niekus H, Nielsen O, Vegt M, Blansjaar BA. Ceftriaxone treatment of penicillin resistant neurosyphilis in alcoholic patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995; 59:194–195. PMID: 7629543.

6. Coleman DL, McPhee SJ, Ross TF, Naughton JL. Secondary syphilis with pulmonary involvement. West J Med. 1983; 138:875–878. PMID: 6613117.

7. Darwish BS, Fowler A, Ong M, Swaminothan A, Abraszko R. Intracranial syphilitic gumma resembling malignant brain tumour. J Clin Neurosci. 2008; 15:308–310. PMID: 18187326.

8. Fargen KM, Alvernia JE, Lin CS, Melgar M. Cerebral syphilitic gummata : a case presentation and analysis of 156 reported cases. Neurosurgery. 2009; 64:568–575. discussioin 575-576. PMID: 19240620.

9. Gentile JH, Viviani C, Sparo MD, Arduino RC. Syphilitic meningomyelitis treated with ceftriaxone : case report. Clin Infect Dis. 1998; 26:528. PMID: 9502500.

10. Holland BA, Perrett LV, Mills CM. Meningovascular syphilis : CT and MR findings. Radiology. 1986; 158:439–442. PMID: 3941870.

11. Horowitz HW, Valsamis MP, Wicher V, Abbruscato F, Larsen SA, Wormser GP, et al. Brief report : cerebral syphilitic gumma confirmed by the polymerase chain reaction in a man with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:1488–1491. PMID: 7969298.

12. Lee CW, Lim MJ, Son D, Lee JS, Cheong MH, Park IS, et al. A case of cerebral gumma presenting as brain tumor in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative patient. Yonsei Med J. 2009; 50:284–288. PMID: 19430565.

13. Lee JP, Koo SH, Jin SY, Kim TH. Experience of meningovascular syphilis in human immunodeficiency virus infected patient. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009; 46:413–416. PMID: 19893736.

14. Lukehart SA, Hook EW 3rd, Baker-Zander SA, Collier AC, Critchlow CW, Handsfield HH. Invasion of the central nervous system by Treponema pallidum : implications for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1988; 109:855–862. PMID: 3056164.

15. Marra CM, Boutin P, McArthur JC, Hurwitz S, Simpson PA, Haslett JA, et al. A pilot study evaluating ceftriaxone and penicillin G as treatment agents for neurosyphilis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis. 2000; 30:540–544. PMID: 10722441.

16. Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Smith SL, Lukehart SA, Rompalo AM, Eaton M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients with syphilis : association with clinical and laboratory features. J Infect Dis. 2004; 189:369–376. PMID: 14745693.

17. Oblu N. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 1975. New York: Elsevir.

18. Pall HS, Williams AC, Stockley RA. Intracranial gumma presenting as a cerebral tumour. J R Soc Med. 1988; 81:603–604. PMID: 3184093.

19. Rolfs RT, Joesoef MR, Hendershot EF, Rompalo AM, Augenbraun MH, Chiu M, et al. The Syphilis and HIV Study Group. A randomized trial of enhanced therapy for early syphilis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997; 337:307–314. PMID: 9235493.

20. Shann S, Wilson J. Treatment of neurosyphilis with ceftriaxone. Sex Transm Infect. 2003; 79:415–416. PMID: 14573840.

22. Uemura K, Yamada T, Tsukada A, Enomoto T, Yoshii Y, Nose T. Cerebral gumma mimicking glioblastoma on magnetic resonance images--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1995; 35:462–466. PMID: 7477692.

Fig. 1

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the patient. A : The preoperative T1-weighted images showed a round mass-like lesion with isointensity in the peripheral and hypointensity in the central portion of the left frontal region. B : Non-contrast-enhanced, T1-weighted image demonstrated severe cerebral edema around the enhancing mass. C : Sagittal sections revealed a mass adjacent to the enhanced dura over the cerebral convexity. D, E and F : Three months after operation, the postoperative MRI scans showed that the rim enhancing mass in the left frontal region had disappeared with a small amount of remaining extraaxial fluid collection.

Fig. 2

Intraoperative and histopathological findings of a central nervous system gumma. A : The cerebral parenchyma was severely adhesive to the dura. B : The lesion had a rubbery appearance and was yellowish in color. En bloc resection was performed. C : High-power view of the mass showing occlusion of small arterioles as endoarteritis obliterans, and spirochetes were not detected on Warthin-Starry staining of this region (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×400). D : The portion immediately below the meninges containing necrotic material infiltrated with predominantly plasma cells (×100). E : The peri-vascular region with fibrosis contained lymphocytes and plasma cells (×400). F : Parenchymal infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the gumma of the brain (×400).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download