Abstract

Simultaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage and infarction is a quite rare presentation in a patient with a spontaneous dissecting aneurysm of the anterior cerebral artery. Identifying relevant radiographic features and serial angiographic surveillance as well as mode of clinical manifestation, either hemorrhage or infarction, could sufficiently determine appropriate treatment. Enlargement of ruptured aneurysm and progressing arterial stenosis around the aneurysm indicates impending risk of subsequent stroke. In this setting, prompt treatment with stent-assisted endovascular embolization can be a reliable alternative to direct surgery. When multiple arterial dissections are coexistent, management strategy often became complicated. However, satisfactory clinical results can be obtained by acknowledging responsible arterial site with careful radiographic inspection and antiplatelet medication.

Arterial dissection occurring at the vertebrobasilar system often presents as subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), while dissecting aneurysm at the anterior circulation tends to manifest infarction1,2,6,7). Although the exact prevalence has not been reported, spontaneous dissection at the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) is infrequent, and its presentation as simultaneous occurrence of infarction and SAH is quite rarer2,3,6-8,10,11). Treatment of symptomatic ACA dissection should be directed to prevent further progression of the stroke on the basis of clinical presentation, either hemorrhage or infarction. Managements include conservative, endovascular, and direct surgical method1,4,5).

When multifocal extracranial dissections are coexistent with such symptomatic intracranial dissection, management strategies often became annoying and complicated. In this condition, treatment should be kept pace with serial angiographic and close clinical surveillance2,9).

We describe a case of spontaneous ACA dissecting aneurysm presenting with simultaneous SAH and infarction in a young adult with multiple extracranial dissections with emphasis on clinical manifestation and serial angiographic follow-ups.

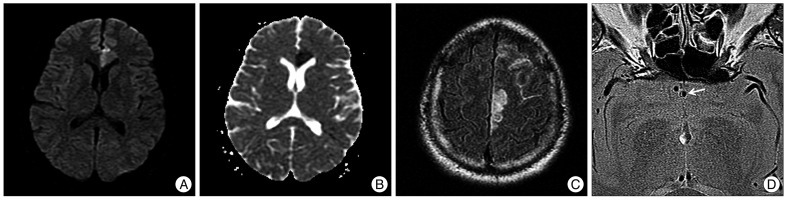

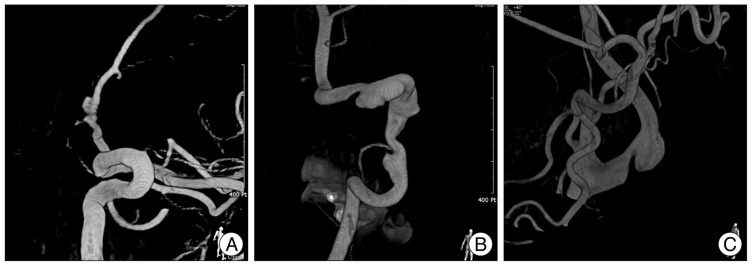

This 37-year-old man with hypertension came to the Emergency room with complaints of sudden onset headache and right leg weakness after he stretched and yawned. Neurological examination showed alert mental state, frontal headache, and grade III weakness of the right leg. He had no remarkable past medical history, except nonspecific dizziness and headache since he was 25 years old. Head computed tomogram (CT) revealed scattered SAH at the left frontal convexities. A magnetic resonance (MR) images showed acute infarction at the rostrum of the left corpus callosum and double-lumen signal with high-signal hemorrhage (Fig. 1). Catheter angiogram showed multifocal dissections at the left carotid bulb and right vertebral artery with tiny aneurysm at the left proximal A2 (Fig. 2). His paresis seemed to be attributed to the infarction. After 3 days, dual antiplatelet agents were prescribed to prevent further ischemia and his weakness was gradually improved.

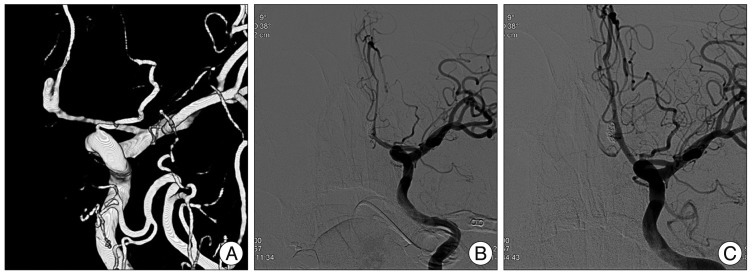

He underwent two more CT angiograms during the next months. Final angiogram revealed enlargement of the left A2 aneurysm and progression of focal stenosis along the ACA (Fig. 3A). Endovascular intervention was performed under a general anesthesia by placing a 4.5×28 mm Enterprise stent (Cordis Neurovascular, Miami Lakes, FL, USA) through the A1 into the A2 segment, and deploying three Axium detachable helix coils (ev3 Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) into the aneurysm sac. Postoperative control angiogram revealed successful coil packing and flow preservation through the bilateral A2 segments (Fig. 3B). Six months postoperatively, angiogram showed neither growth of aneurysms nor recurrence of stenosis (Fig. 3C). He has no neurologic deficits and awaits another angiogram 12 months hereafter.

Recently, intracranial dissection or dissecting aneurysm is increasingly recognized. It is attributed to heightened clinical awareness and subsequent identification of relevant clinical and radiological features. Nevertheless, various nonspecific manifestations often made prompt diagnosis and management difficult. Vertebrobasilar dissecting aneurysms generally present with SAH because of its elongated subarachnoid course, and are more frequently reported1,2,6,7). Those confined in the anterior circulation are mainly involved in the supraclinoid carotid and middle cerebral arteries, and present with either hemorrhage or ischemia2).

Isolated ACA territory infarction is very rare, representing 0.5-3% of all ischemic strokes, and angiographically proven ACA dissection is responsible for 47% of them10,11). The ACA dissection is more difficult to identify than vertebrobasilar system because of narrower vessel calibers and more curved features. Therefore, if encountered with ACA territory infarction particularly in young patients without trauma or existing atherosclerotic vasculopathy, clinicians should reckon the possibility of dissection and warn the risk of bleeding or re-occlusion6).

There are many radiographic clues suggesting a dissection, including "double-lumen", "intimal flap", "pear and string", "string", "tapered occlusion", and "hyperintense intramural signal" on conventional angiogram, MRI, MRA, or CTA1,5,8,10). Besides other features, dynamic change on serial angiography is the most culprit evidence of dissecting aneurysm. In our report, false lumen with hyperintense rim around the true lumen on MRI, and serial angiographic changes such as aneurysm enlargement and progressive vessel narrowing the aneurysm are definite clues of dissection. All these findings warrant immediate treatment other than close observation.

A dissection occurring between the internal elastica and the media mainly presents as an ischemic stroke with occlusion of the affected portion. In this circumstance, pushing the arterial wall outward in radial fashion with stent that guarantee lumen patency could be a primary treatment option. And, antiplatelet medication with serial angiography should be considered as strong additional measures for sub-intimal dissection12). Another subtype, sub-adventitial dissection between the media and the adventitia usually presents as hemorrhage and leads to poorer prognosis than ischemic counterpart1,3,11,12). In this subtype of loosely woven vessel wall, treatment should be directed to seal off the leakage to prevent further hemorrhage by occluding the diseased vessel lumen harboring ruptured aneurysm. In this case, simultaneous occurrence of SAH and infarction represents both sub-intimal and sub-adventitial dissection. This indicates more severe and deeper dissection which potentially results in recurrent event of hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke.

Extracranial arterial dissection is recognized as a cause of transient ischemic attack and primary or recurrent stroke. However, clinical presentation is subtle and unnoticed in most cases. Because of considerable rate of spontaneous healing, there remains controversy over optimum treatment. But, antiplatelet medications are current standard for care unless contraindicated or unstable1,9). In this case, it is not certain that peculiar angiographic features seen in the carotid bulb and the V4 are true dissections or mere fibromuscular dysplasia. However, paucity of previous symptoms and unchanged angiographic morphology warrant conservative therapeutic strategies, irrespective of true etiologies.

If hemorrhage is the first presentation, or angioarchitecture is ever changing, antiplatelet medications would not be sufficient1,3-5). When such alteration is detected, proximal occlusion, resection of lesion, or endovascular obliteration with or without revascularization should be carefully selected. It should be decided after careful assessment of ruptured aneurysm, vessels proximal and distal to the aneurysm, and status of collaterals. Endovascular treatment can be a strong alternative when surgical approach is not feasible due to inherent fragility in vessel wall. Stent-assisted coiling could salvage proximal parent artery simultaneously obliterating aneurysm without compromising vessel. If vascular territory infarction already occurred and chance of recovery is quite low, obliteration without revascularization also might be considered. As previously reported, the outcome of the ACA dissection patients is better than that of the other ACA stroke patients after appropriate treatment10).

An ACA dissecting aneurysm presenting with acute onset SAH and infarction in a young adult patient should be regarded as a high risk for subsequent stroke, albeit quite rarely. Although radiographic findings are often uncertain for dissection, serial angiographic surveillance is crucial to detect an on-going risk of stroke. When changes in the angiographic architecture are identified, endovascular or surgical management with or without revascularization should be meticulously considered.

References

1. Amagasaki K, Yagishita T, Yagi S, Kuroda K, Nishigaya K, Nukui H. Serial angiography and endovascular treatment of dissecting aneurysms of the anterior cerebral and vertebral arteries. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1999; 91:682–686. PMID: 10507393.

2. Huang YC, Chen YF, Wang YH, Tu YK, Jeng JS, Liu HM. Cervicocranial arterial dissection : experience of 73 patients in a single center. Surg Neurol. 2009; 72(Suppl 2):S20–S27. discussion S27. PMID: 19150115.

3. Inoue T, Fujimura M, Matsumoto Y, Kondo R, Inoue T, Shimizu H, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral infarction caused by anterior cerebral artery dissection treated by endovascular trapping. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010; 50:574–577. PMID: 20671384.

4. Jensen MB, Chacon MR, Aleu A. Cervicocerebral arterial dissection. Neurologist. 2008; 14:5–6. PMID: 18195650.

5. Kitanaka C, Tanaka J, Kuwahara M, Teraoka A, Sasaki T, Takakura K, et al. Nonsurgical treatment of unruptured intracranial vertebral artery dissection with serial follow-up angiography. J Neurosurg. 1994; 80:667–674. PMID: 8151345.

6. Koyama S, Kotani A, Sasaki J. Spontaneous dissecting aneurysm of the anterior cerebral artery : report of two cases. Surg Neurol. 1996; 46:55–61. PMID: 8677490.

7. Kurino M, Yoshioka S, Ushio Y. Spontaneous dissecting aneurysms of anterior and middle cerebral artery associated with brain infarction : a case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2002; 57:428–436. discussion 436-438. PMID: 12176212.

8. Ohkuma H, Suzuki S, Kikkawa T, Shimamura N. Neuroradiologic and clinical features of arterial dissection of the anterior cerebral artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003; 24:691–699. PMID: 12695205.

9. Redekop GJ. Extracranial carotid and vertebral artery dissection : a review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008; 35:146–152. PMID: 18574926.

10. Sato S, Toyoda K, Matsuoka H, Okatsu H, Kasuya J, Takada T, et al. Isolated anterior cerebral artery territory infarction : dissection as an etiological mechanism. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010; 29:170–177. PMID: 19955742.

11. Suzuki K, Mishina M, Okubo S, Abe A, Suda S, Ueda M, et al. Anterior cerebral artery dissection presenting subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral infarction. J Nippon Med Sch. 2012; 79:153–158. PMID: 22687360.

12. Yonas H, Agamanolis D, Takaoka Y, White RJ. Dissecting intracranial aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 1977; 8:407–415. PMID: 594878.

Fig. 1

Magnetic resonance images at admission show an acute ischemia of the left rostral corpus callosum in diffusion-weighted image (A) and apparent diffusion coefficient map (B). A fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image shows both infarction and hemorrhage of the left frontal convexity (C) and axial source image indicates hyperintense double lumen sign at the proximal anterior cerebral artery (white arrow) (D).

Fig. 2

Angiogram shows multifocal dissections at the left anterior cerebral artery (A), right vertebral artery (V3) (B) and right carotid bulb (C).

Fig. 3

After 4 months, angiogram shows superior elongation of the aneurysm sac and progressing stenosis along the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) (A). Postoperative angiogram shows complete filling of the aneurysm (B), and 6-month follow-up angiogram depicts no residual filling and straightening of the ACA due to a deployed stent (C).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download