Abstract

Despite the remarkable developments in neurosurgical and neuro-interventional procedures, the optimal treatment for large or giant partially thrombosed aneurysms with a mass effect remains controversial. The authors report a case of a partially thrombosed aneurysm with a mass effect, which was successfully treated by stent-assisted coil embolization. A 41-year-old man presented with headache. Brain computed tomography depicted an 18×18 mm sized thrombosed aneurysm in the interpeducular cistern. More than 80% of the aneurysm volume was filled with thrombus and the canalized portion beyond its neck measured 6.8×5.6 mm by diagnostic cerebral angiography. Stent-assisted endovascular coiling was performed on the canalized sac and the aneurysm was completely obliterated. Furthermore, most of the thrombosed aneurysm disappeared in the interpeduncular cistern was clearly visualized follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging conducted at 21 months. The authors report a case of selective coiling of a large, partially thrombosed basilar tip aneurysm.

Partially thrombosed aneurysms are a diverse collection of complex aneurysms characterized by organized intraluminal thrombus and a solid mass7). These aneurysms are range from large to giant and frequently present with cranial neuropathy related to a mass effect. Large posterior communicating artery (PComA), basilar tip, and superior cerebellar artery aneurysms may cause oculomotor nerve palsy16,20). Neurosurgical approaches often require techniques other than conventional clipping, such as, thrombectomy with clip reconstruction, and are frequently associated with complications. Bypass surgery may produce good outcomes, but is not possible in every case, especially in those affecting the posterior circulation. However, although surgery for these aneurysms is difficult, endovascular treatment, consisting of proximal vessel occlusion or selective coil embolization with or without stent, generally is straightforward. On the other hand, the possibility of coil migration into thrombus and the subsequent reopening of the aneurysm lumen and lack of control of the mass effect are well-known problems of selective coil embolization. The authors report a rare case of a partially thrombosed aneurysm with a mass effect that was successfully treated by stent-assisted selective coil embolization.

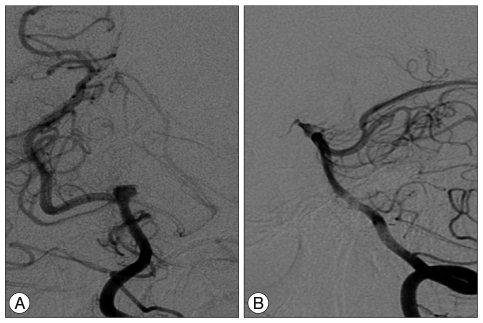

A 41-year-old man presented with headache. Brain computed tomography revealed an 18×18 mm sized mass in interpeducular cistern (Fig. 1), and diagnostic cerebral angiography showed a canalized portion sized 6.8×5.6 mm (Fig. 2).

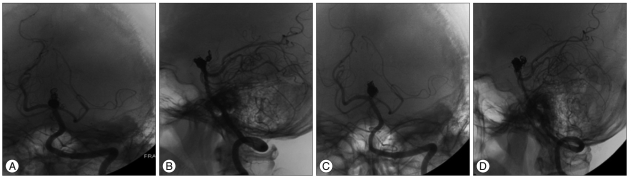

After reviewing the surgical and endovascular options, the authors chose endovascular treatment. Dual antiplatelet therapy (100 mg aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel) was pretreated for 5 days. The endovascular procedure was performed under intravenous sedation using Propofol and Remifentanil. At the beginning of the procedure, a 5000 IU bolus intravenous injection of heparin was administered followed by 1000 IU per hour to achieve an activated clotting time (ACT) of 250 to 300 seconds during the procedure. The right femoral artery was accessed using a 6F sheath. A 3.5×20 mm Neuroform3 stent (Boston Scientific/Target Therapeutic, Fremont, CA, USA) was deployed from the right posterior cerebral artery (PCA, P1) to the basilar artery. The left PCA was supplied from the left internal carotid artery via the PcomA, and was not visualized in vertebral angiography (Fig. 2). An Excelsior SL10 microcatheter (Boston Scientific/Target Therapeutic, Fremont, CA, USA) was then introduced into the canalized sac of the aneurysm through the interstices of implanted stent struts and ten bare platinum coils (6 : Microplex 10, MicroVention, Aliso Viejo, CA and 4 : GDC 10, Boston Scientific/Target) deployed into the aneurysm. Pulsatile movement of the coil mass in the aneurysm was noticed by fluoroscopy until the 4th coil was placed. The third and 4th coils were pushed intentionally into the thrombosed portion to eliminate the possibilities that it was organized or fragile, and the coils were then embedded into this region. The aneurysm pulsation was ceased after complete coiling (Fig. 3). The IV heparinization targeting ACT of 250 to 300 seconds was continued for one day and was followed by dual antiplatelet therapy for 6 weeks. The patient's perioperative neurological state was unchanged and his subsequent clinical course was uneventful.

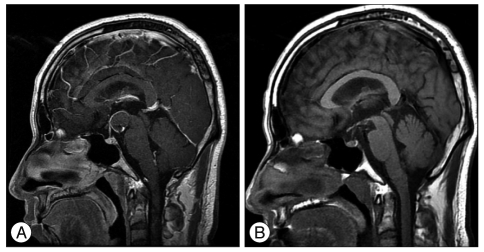

On postoperative day 1, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the 18×18 mm sized mass, which compressed the adjacent structure in the interpeduncular cistern. The coiled sac was less than 20% of the total volume of the aneurysm. Follow-up brain MRI on postoperative month 21 revealed an obviously shrunken thrombosed aneurysm and the whole interpeduncular cistern (Fig. 4), and the compaction of coiled mass from thrombosed portion to forward and downward direction was shown in cerebral angiography (Fig. 5).

Large and giant partially thrombosed aneurysms are sometimes difficult to treat by microsurgical or endovascular means. Surgical treatment is often problematic when an aneurysm is located in the posterior circulation or has a wide neck, calcification, or intra-aneurismal thrombosis. In addition, partially thrombosed aneurysms may not be amenable to clipping, because the aneurysmal domes tend to become imbedded in deep parenchyme5,14).

Some authors have suggested that the vasa vasorum of the aneurysmal wall plays a pivotal role in the growth of aneurysms with intraaneurysmal thrombus due to proliferation, inflammation, and rupture, and have advised that the target of treatment for these aneurysms should be the outer aneurysmal wall not on the luminal side1,13). The two potential sources of vasa vasorum are adventitial and luminal blood flow3), and both are involved in aneurysmal growth17,19). However, the relative contributions made by these two potential sources remain unknown. In addition, intracranial arteries have few vasa vasorum, except for proximal segments of the intracranial internal carotid and the VA as it pierces the dura2). Although endovascular treatment theoretically does not obstruct the adventitial source of the aneurysmal wall containing thrombus, recent studies have suggested that luminal sources may play a dominant role in aneurysmal growth in most cases4,6,7,9).

Ferns et al.7) proposed that the growths of partially thrombosed aneurysms are increased by dissection of the aneurysm wall, and suggested that after parent artery occlusion (PAO), aneurysmal growth does not occur because dissections originating in the lumen of an aneurysm cannot occur and after selective coiling of the aneurismal lumen, although dissections can still occur in the remaining neck due to the presence of continuous hemodynamic forces. PAO with or without bypass surgery is the preferred method for treating these lesions, and is associated with a relatively low procedural complication rate7,9,15). However, PAO is not always possible, especially in the posterior circulation and in the absence of sophisticated bypass surgery. Kim and Choi12) reported midterm outcomes for 18 partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms treated by selective coil embolization and compared their recanalization rates with those of non-thrombosed aneurysms. They reported that the recanalization rate of partially thrombosed aneurysms was 77.8%, which was about fivefold higher than that of non-thrombosed aneurysms. In another study7), after coiling partially thrombosed aneurysms, 75% showed recanalization at follow-up, and 63% of aneurysms were retreated. In contrast, aneurysm growth does not occur after PAO. Furthermore, in a series of ten patients with largely thrombosed aneurysms, it was found that the endovascular treatment of aneurysms is safe with a 30% rate of midterm recanalization4). The migration of coils into a thrombus by arterial pulsation is referred to as the 'water-hammer effect', and collateralization of the vasa vasorum is a possible cause of failed treatment9). In a report on 17 unruptured large and giant aneurysms that presented with cranial neuropathy, symptom improvements were found to be as good after selective coiling as after PAO20). Ferns et al.7) recommended that to prevent persistent growth of partially thrombosed aneurysms, the neck of these aneurysms should be completely occluded by stents, and although it requires confirmation, two studies concluded that the placement of stents can completely heal the aneurysm neck and prevent further growth11,18).

Fiorella et al.8) reported that a giant partially thrombosed midbasilar trunk aneurysm was successfully treated using the pipeline embolization device (PED) only without coiling; conventional angiography performed on postoperative day 7 showed anatomic reconstruction of the basilar artery and complete occlusion of the circumferential aneurysm. However, more long-term outcome data and further analysis of PED treatment is required.

During the procedure, we found a marked decrease in aneurysmal pulsation as the patent sac was obliterated by coils, which suggests that the pulsation control in the sac by any means can protect against continuous growth with progressing symptoms from mass effect. In the presented case, most of the thrombosed aneurysm disappeared and the previously obscured interpeduncular cistern was observed clearly by MRI after 21 months postoperatively. The compaction of coiled mass usually progressed from aneurysmal neck to dome in current cases of selective coiling for thrombosed aneurysm. In the present case, the compaction of coiled mass from thrombosed portion toward the neck by shrinkage of aneurysm was shown on cerebral angiography at this time (Fig. 5). The mechanism of this shrinkage has not yet been established. The authors suggest that the mechanism might be caused from phagocytosis by infiltrated macrophage10).

An excellent clinical and radiological outcome was achieved after selective coiling with stent deployment in a partially thrombosed basilar tip aneurysm. If proximal vessel occlusion is not possible, selective coiling or flow diversion with a newly developed microcell stent are often the only alternative treatments that offer the possibility of a favorable clinical outcome. However, the effectiveness of endovascular procedure according to the different pathogeneses and complications should be kept in mind.

Acknowledgements

This present research was conducted by the research fund of Dankook University in 2009.

References

1. Alvarez H. Etiology of giant aneurysms and their treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009; 30:E8. author reply E9-E10. PMID: 18945792.

2. Aydin F. Do human intracranial arteries lack vasa vasorum? A comparative immunohistochemical study of intracranial and systemic arteries. Acta Neuropathol. 1998; 96:22–28. PMID: 9678510.

3. Bo WJ, McKinney WM, Bowden RL. The origin and distribution of vasa vasorum at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery with atherosclerosis. Stroke. 1989; 20:1484–1487. PMID: 2815182.

4. Cho YD, Park JC, Kwon BJ, Hee Han M. Endovascular treatment of largely thrombosed saccular aneurysms : follow-up results in ten patients. Neuroradiology. 2010; 52:751–758. PMID: 19921162.

5. Choi IS, David C. Giant intracranial aneurysms : development, clinical presentation and treatment. Eur J Radiol. 2003; 46:178–194. PMID: 12758113.

6. Ferns SP, Sprengers ME, van Rooij WJ, Rinkel GJ, van Rijn JC, Bipat S, et al. Coiling of intracranial aneurysms : a systematic review on initial occlusion and reopening and retreatment rates. Stroke. 2009; 40:e523–e529. PMID: 19520984.

7. Ferns SP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, van den Berg R, Majoie CB. Partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms presenting with mass effect : long-term clinical and imaging follow-up after endovascular treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010; 31:1197–1205. PMID: 20299431.

8. Fiorella D, Kelly ME, Albuquerque FC, Nelson PK. Curative reconstruction of a giant midbasilar trunk aneurysm with the pipeline embolization device. Neurosurgery. 2009; 64:212–217. discussion 217. PMID: 19057425.

9. Iihara K, Murao K, Yamada N, Takahashi JC, Nakajima N, Satow T, et al. Growth potential and response to multimodality treatment of partially thrombosed large or giant aneurysms in the posterior circulation. Neurosurgery. 2008; 63:832–842. discussion 842-844. PMID: 19005372.

10. Jiménez-Heffernan JA, Corbacho C, Cañizal JM, Pérez-Campos A, Vicandi B, López-Ibor L, et al. Cytological changes induced by embolization in meningiomas. Cytopathology. 2012; 23:57–60. PMID: 21214650.

11. Kessler IM, Mounayer C, Piotin M, Spelle L, Vanzin JR, Moret J. The use of balloon-expandable stents in the management of intracranial arterial diseases : a 5-year single-center experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005; 26:2342–2348. PMID: 16219843.

12. Kim SJ, Choi IS. Midterm outcome of partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms treated with guglielmi detachable coils. Interv Neuroradiol. 2000; 6:13–25. PMID: 20667178.

13. Krings T, Alvarez H, Reinacher P, Ozanne A, Baccin CE, Gandolfo C, et al. Growth and rupture mechanism of partially thrombosed aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. 2007; 13:117–126. PMID: 20566139.

14. Lawton MT, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Chang EF, Yu T. Thrombotic intracranial aneurysms : classification scheme and management strategies in 68 patients. Neurosurgery. 2005; 56:441–454. discussion 441-454. PMID: 15730569.

15. Lubicz B, Leclerc X, Gauvrit JY, Lejeune JP, Pruvo JP. Giant vertebrobasilar aneurysms : endovascular treatment and long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery. 2004; 55:316–323. discussion 323-326. PMID: 15271237.

16. Mansour N, Kamel MH, Kelleher M, Aquilina K, Thornton J, Brennan P, et al. Resolution of cranial nerve paresis after endovascular management of cerebral aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 2007; 68:500–504. discussion 504. PMID: 17597189.

17. Nagahiro S, Takada A, Goto S, Kai Y, Ushio Y. Thrombosed growing giant aneurysms of the vertebral artery : growth mechanism and management. J Neurosurg. 1995; 82:796–801. PMID: 7714605.

18. Saatci I, Cekirge HS, Ozturk MH, Arat A, Ergungor F, Sekerci Z, et al. Treatment of internal carotid artery aneurysms with a covered stent : experience in 24 patients with mid-term follow-up results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004; 25:1742–1749. PMID: 15569740.

19. Schubiger O, Valavanis A, Wichmann W. Growth-mechanism of giant intracranial aneurysms; demonstration by CT and MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1987; 29:266–271. PMID: 3614624.

20. van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M. Unruptured large and giant carotid artery aneurysms presenting with cranial nerve palsy : comparison of clinical recovery after selective aneurysm coiling and therapeutic carotid artery occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008; 29:997–1002. PMID: 18296545.

Fig. 2

The cerebral angiography shows that the patent portion of the aneurysm has an inverted triangular shape and measured 6.8×5.6 mm. A : Anteropostrior view. B : Lateral view.

Fig. 3

Cerebral angiographs during and after the procedure. A : During procedure. A 3.5×20 mm stent is being deployed from the right PCA to the basilar artery, because the left PCA, which is supplied from the left internal carotid artery via PCom, is not visualized by vertebral angiography. B : After procedure. The aneurysm is found to have been completely obliterated by immediate post-operative angiography and the right PCA is patent. The coils pushed into the thrombosed portion are also visualized. PCA : posterior cerebral artery, PCom : posterior communicating.

Fig. 4

Postoperative brain MRI. A : On postoperative day 1, brain MRI shows a 18×18 mm sized mass compressing the adjacent structures in the interpeduncular cistern. B : At 21 months postoperatively, most of the thrombosed aneurysm has disappeared and the interpeduncular cistern is clearly observed. MRI : magnetic resonance imaging.

Fig. 5

Postoperative angiography. A (anteroposterior view) and B (lateral view) : After procedure, the shape of coiled mass is shown in cerebral angiography. C (anteropostrior view) and D (lateral view) : On post operative month 21, cerebral angiography shows the compaction of coiled mass from thrombosed portion toward the neck by shrinkage of aneurysm.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download