INTRODUCTION

Since 2017, South Korea has officially become an aged society, with an aging rate exceeding 14% [

123], and it is not uncommon for a surgeon to encounter elderly patients seeking surgical treatment after a cancer diagnosis. A number of organizations or organization subcommittees have been set up for the proper care and management of elderly patients [

4], and, as part of this, the Korean Surgical Society has recently launched the Korean Geriatric Surgery Society [

5].

The tendency toward a high prevalence of comorbid conditions in elderly patients has frequently been reported [

67], and their safety and well-being after cancer surgery have become tremendous concerns. Advanced age has often been reported as one of the influential factors associated with refusing surgery by cancer patients [

89]. Concerns regarding disappointing recovery after successful surgery, along with frailty and overall life expectancy, have been suggested to influence their decision.

Although the mortality from gastric cancer alone is decreasing, it still is one of the most common cancers with high mortality in South Korea [

1011]. With the rapid aging of the population, cancer incidence and mortality are also increasing proportionally, and we expect to encounter more elderly gastric cancer patients over time. Thus, we need to verify the postoperative quality of life (QoL) of elderly gastric cancer patients to minimize patient dissatisfaction associated with the dismal gap between reality and expectations associated with gastric cancer and related surgery [

12].

The aim of this study was to investigate how the QoL of elderly gastric cancer patients differed from that of younger patients during the perioperative period. We also compared the QoL outcomes between the early- and late-2010s to investigate how the QoL of elderly gastric cancer patients has changed over time in the aging population.

Go to :

METHODS

Study design and participants

QoL and clinical data were retrospectively evaluated with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyungpook National University Hospital (No. KNUH 2021-10-028). The IRB waived the requirement for informed consent for this study.

Between 2010 and 2019, a total of 566 patients, aged 55 years or older, underwent a distal subtotal gastrectomy for stage I gastric adenocarcinoma in our hospital. The stage grouping was in accordance with the 8th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control classification. The complete set of QoL data from the preoperative, postoperative 3-month, and postoperative 1-year periods were available for 318 of 566 patients. Patients with combined surgeries or histories of gastric resection that could influence their QoL were excluded, and one patient with combined surgery (total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis) for familial adenomatous polyposis and 2 patients with previous partial gastrectomies for benign gastric diseases were excluded. After these exclusions, data from 315 patients remained for the final analysis.

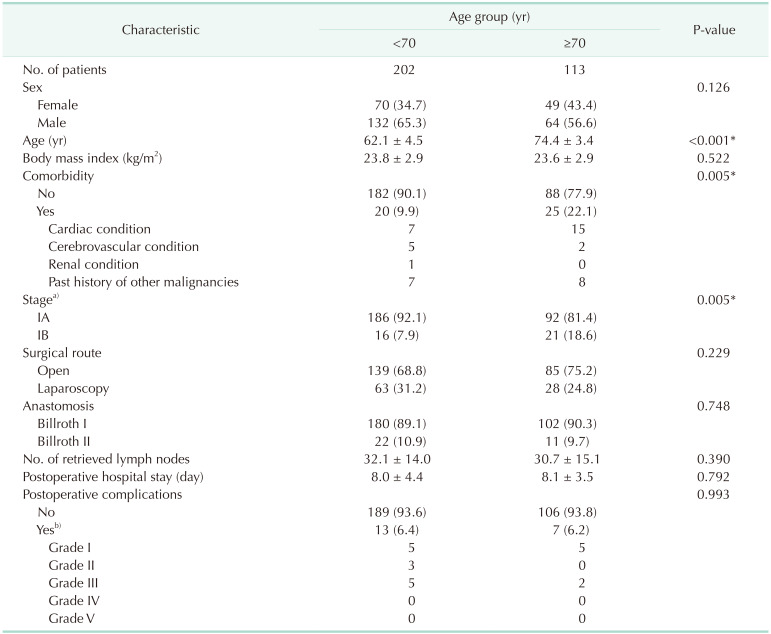

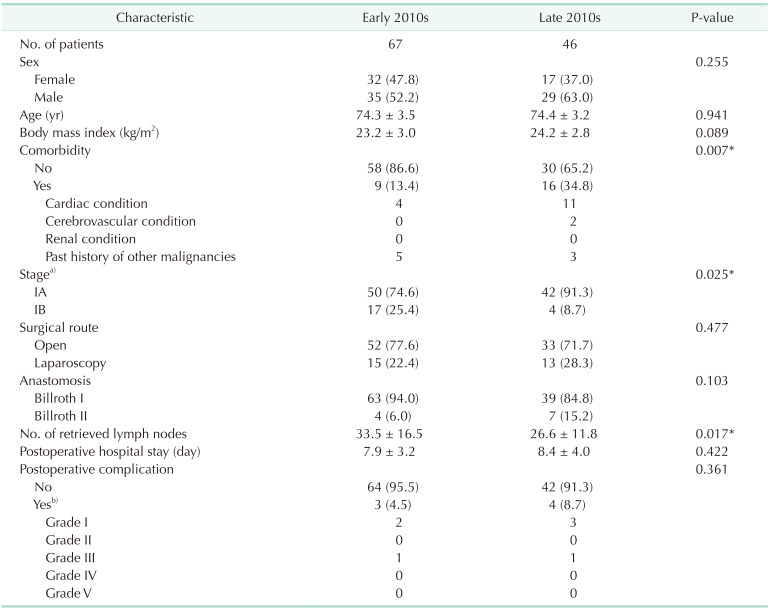

The patients were grouped into younger and older groups by age (<70 years vs. ≥70 years), and there were 202 and 113 patients available for each group. To understand the QoL trends in older patients during the 2010s, the older patients were further grouped by their year of surgery into the early-2010s (2010–2014, n = 67) and the late-2010s (2015–2019, n = 46) groups.

QoL assessment

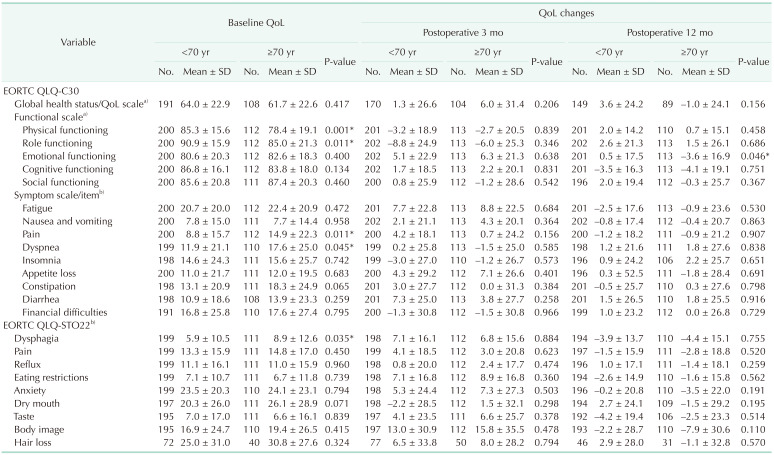

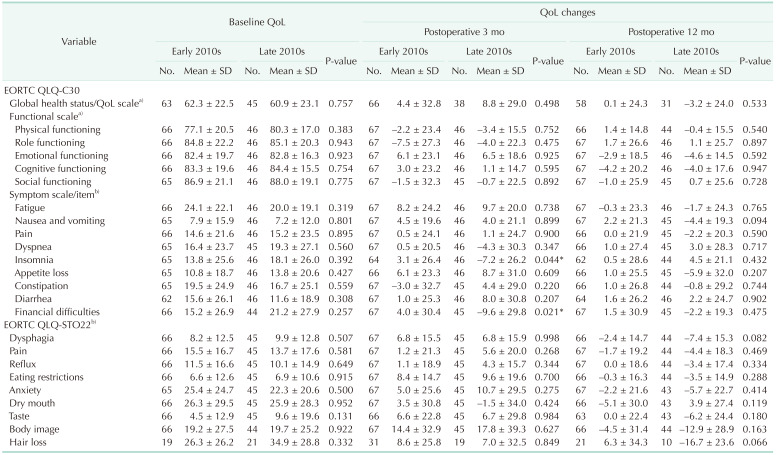

The Korean version of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ) core (-C30) and gastric cancer-specific (-STO22) modules were used to assess QoL [

13]. All patient responses were self-reported without clinician intervention. Preoperative QoL was evaluated upon admission of the patient for surgery. Postoperative QoL was evaluated at scheduled visits to our outpatient department at 3-months and 1-year postoperatively. The patients were asked to respond to 52 items for each time period, and the responses were transformed into 24 scale scores of 0–100 in accordance with the scoring manual provided by the EORTC. A lower score indicated better QoL with 6 exceptions. For the global health status/QoL scale and the 5 functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), a lower score indicated worse QoL.

Statistical analysis

The clinical and QoL outcomes of the younger (<70 years) and older (≥70 years) groups were compared. In the older group, the outcomes in the early and late 2010s were further compared. The demographic values were compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables and Student t-tests for continuous variables. The QoL outcomes were compared using Student’s t-tests. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, ver. 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Even though QoL disadvantages in elderly gastric cancer patients were apparent by the absolute values in some scales, the extent of postoperative QoL shifting was not very different from that of the younger patients. Compared to the first half of the 2010s, more elderly patients with comorbidities underwent surgery with equivalent or better (insomnia and financial difficulties at 3-months) QoL outcomes during the second half of the 2010s.

While there are a number of studies on general surgical outcomes in elderly gastric cancer patients, very little is known about their QoL. In terms of surgical outcomes, several studies suggested comparable outcomes for complications or morbidities in elderly and younger patients [

141516]. While these studies defined the elderly groups by an age of 70 years or older, one study defined the elderly group using the age of 80 years or older [

17], which showed higher complication rates for pneumonia, delirium, and urinary tract infections in the elderly group. While the same may not be true for patients with extreme age, at least in patients in their 70s, there were consistent results, showing surgical morbidities at a rate comparable to that of younger patients.

However, unlike surgical morbidities, the reported outcomes on the QoL of elderly patients were inconsistent. Before the widespread use of generic QoL tools in the form of a self-answered questionnaire [

1819], several tools were used to attempt to measure QoL, and the Spitzer QoL index was one of them [

20]. A previous report assessed postoperative QoL in elderly gastric cancer patients using the Spitzer QoL index [

21] and found that both younger (65–74 years) and older (>74 years) age groups showed good QoL outcomes, which were comparable to the outcomes reported by another study in much younger patients (<65 years) [

22].

There have been more recent attempts to assess the QoL of elderly gastric cancer patients using the EORTC QLQs, which are designed in the form of self-answered questionnaires and are commonly used currently. In an attempt to assess the QoL of elderly gastric cancer patients after laparoscopic gastrectomy [

15], QoL comparisons were made up to 1-year postoperatively in 21 elderly patients and 50 young patients, which showed no QoL disadvantage for elderly patients. In contrast, in a study comparing the QoL of 57 elderly and 74 young patients up to a year after surgery, QoL disadvantages in elderly patients with significant postoperative deteriorations on multiple scales were reported [

14]. The study included patients in more physically demanding circumstances, such as those with advanced-stage gastric cancer or undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy, and the results were somewhat inconsistent with the outcomes of other studies, including ours. We constructed a larger pool of patients consisting of 113 elderly and 202 younger patients during a longer time period of a decade. We also controlled the homogeneity of the study group and minimized external influences by limiting our inclusion criteria to those with stage I gastric cancer only. Having a larger pool of homogeneous patients in our study might have resulted in conflicting outcomes without disadvantages for elderly patients in terms of the extent of postoperative QoL deteriorations on most scales.

The reason we designed this study to cover the long study period of a decade was to explore the shift in social and medical trends regarding elderly gastric cancer patients over the last decade. It has been reported that people undergo health screening when beneficial health outcomes are expected by doing so [

2324]. Due to the increased comorbidities and shorter life expectancy of older people, there are concerns about unmet expectations among older people, which is known to have a strong influence on their decisions not to undergo health screening. As we had a higher percentage of stage IA gastric cancer (92.1%) in the younger group, compared to 81.4% in the older group, we could presume that more younger people are undergoing screening endoscopies, enabling the earlier detection of gastric cancer. However, we found a huge increase in the percentage of stage IA gastric cancer in the older group from 74.6% in the early 2010s to 91.3% in the late 2010s. Based on similar reasoning, we could presume that this was reflected in the trends of higher desires for health among older people during the late 2010s, which led to more screening endoscopies.

Despite a higher percentage of comorbidities (34.8%) in elderly patients in the late-2010s group compared to 13.4% in the early-2010s group, patients in the late-2010s had comparable outcomes in terms of hospital stays, complications, and QoL. This indicates that the decision-making trends for surgical treatment in older gastric cancer patients have shifted over the last decade with more of them opting for surgery, and that the current practice of performing more surgeries on older gastric cancer patients is producing comparable outcomes in terms of their surgical outcomes and QoL.

Our study highlighted the QoL of elderly gastric cancer patients which showed that the extent of their postoperative deterioration did not surpass that of the younger patients. Having this result drawn from a larger pool of homogeneous gastric cancer patients during a decade of clinical practice was the strength of our study. We often encounter elderly gastric cancer patients refusing surgery because of concerns regarding disappointing postoperative recovery. The current findings could become an essential piece of information that could influence their decisions. Moreover, evaluation of our responsiveness to the population aging was another strength of this study.

Our study had some limitations. First, this was a retrospective analysis based on those who had QoL outcomes available for the preoperative, 3-month, and 1-year postoperative periods. While it may be appropriate to discuss postoperative QoL and morbidities, conclusions regarding mortality cannot be made from our study because those who did not survive could not be included in the study as no QoL responses were available. Second, our study considered the patients aged 70 years and over as elderly reflecting the more traditional definition of the elderly rather than age 80 years and older. In fact, more studies are defining the elderly as age 80 years and older to reflect the real clinical practice in the aging population; however, we still do not have enough QoL data collected in patients aged 80 years and over to make a conclusion. We plan to investigate the QoL of patients in their 80s in the future when the sufficient sample size is obtained in the specific age group. Third, our focus was on the QoL of elderly gastric cancer patients, and we did not have data on other parameters such as nutritional profiles and body composition. Even though those were not the focus of our study, having them available for background information could assist in our understanding. Devising a prospective study with such parameters would provide a better understanding, including the mortality, of elderly gastric cancer patients.

Our findings must not be misunderstood as equivalent QoL scores in older and younger patients. The baseline QoL itself during the preoperative period favored younger patients on 2 functional scales (physical and role) and 3 symptom scales (pain and dyspnea on the EORTC QLQ-C30, and dysphagia on the EORTC QLQ-STO22) while the extent of the postoperative changes was not different.

In conclusion, despite baseline QoL differences, elderly gastric cancer patients did as well as younger patients in terms of relative QoL changes after surgery. More elderly gastric cancer patients with comorbidities underwent surgeries in the late 2010s; nonetheless, they did not suffer disadvantages in QoL changes. Thus, the fear of disappointing QoL after surgery alone should not be regarded as a critical determinant in refusing gastrectomy by elderly patients. We need to continue to keep up with the higher desire for health, manifesting in elderly patients.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download