INTRODUCTION

Chronic pain is a major public health issue affecting 20% of the adult population worldwide [

123]. The personal and socioeconomic effects of chronic pain are considered to be at least as great as those of other established healthcare priorities, including cardiovascular disease and cancer [

4]. Although it impacts quality of life in multiple functional domains, including family life, workplace performance, social interactions, and sleep patterns [

12], less than 2% of chronic pain patients have access to a comprehensive specialist pain clinic [

56]. The Declaration of Montreal states that pain management is inadequate across most of the world.

Patients with chronic, intractable pain may benefit from interventional strategies such as intrathecal drug delivery (IDD) systems [

2]. The intrathecal administration of opioid medications through IDD systems permits the delivery of higher drug concentrations into the cerebrospinal fluid with lower concentrations reaching systemic circulation [

7]. This direct action of analgesics on spinal receptors accompanied by reduced drug delivery to the brain via the blood-brain barrier may provide clinical benefits with lower risks of adverse effects compared to systemic opioid therapy [

89]. Therefore, although relegated to one of the interventions of “last resort,” IDD systems should be considered to improve pain control, optimize patient functionality, and minimize the use of systemic pain medications in appropriately selected patients with refractory chronic pain [

10].

Despite these advantages, the substantial costs that arise at the time of surgical implantation (US$16,000 in Korea to US$35,000 in the USA) and difficulties with reimbursement continue to negatively affect IDD system use [

11]. In Korea, the high cost of IDD pump implantation is the main obstacle to its use—except in extremely rare cases. However, since July 2014, the Korean national health insurance (NHI) program began financially supporting 50% of the IDD system implantation cost in select refractory chronic pain patients. Currently, Korean government reimbursement is approved for patients with the following conditions: long-term severe pain (a persistent numerical rating scale [NRS] score ≥ 7), insufficient pain control for 6 months when using other analgesic methods, patient life expectancy > 1 year, and cancer pain that is unresponsive to high doses of oral morphine or an equivalent dose of another narcotic analgesic.

A previous study in eleven patients with non-cancer pain and one cancer patient that underwent IDD pump therapy in Korea indicated that the median time required to reach the financial break-even point was 24.2 months [

12]. The new NHI reimbursement policy may promote wider use of IDD as a treatment option for chronic pain patients in Korea, which would affect the financial break-even point in Korean patients. Therefore, this study was performed to investigate the financial break-even point in patients receiving intrathecal morphine pump (ITMP) implantation since July 2014 after initiation of the NHI reimbursement policy and to assess patient satisfaction.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH; IRB No. H-1601-053-733). Upon IRB approval, we identified patients that received ITMP implantation between July 2014 and May 2016 at the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine of SNUH.

We performed a retrospective database analysis that weighted the pre-implantation and post-implantation claims for ITMP costs and surveyed patients by phone to evaluate the average level of satisfaction after implantation. The requirement for written informed consent was waived by SNUH's IRB.

1. Clinical data in patients with ITMP implantation

Data was extracted from patients' electronic medical records, the operative reports, and the medical progress notes. We included demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients, such as age, gender, height, weight, pain duration, diagnosis, prior surgical history, and underlying diseases (diabetes mellitus and concomitant psychopathologies).

Pain severity was determined using an 11-point NRS score by a retrospective review of the patient's electronic medical records before ITMP as a baseline score and for 1 year after ITMP implantation. Changes in the morphine equivalent daily dosage (MEDD) [

13] before and after ITMP implantation were also investigated, including all opioid medications administered orally, intrathecally, and/or transdermally.

Escalation in daily opioid dosage was investigated over a 1-year period after ITMP implantation in each patient. In addition, concomitant around-the-clock and/or pro re nata analgesics other than strong opioids, including non-opioid/weak opioid analgesics such as tramadol, acetaminophen, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, were reviewed. Interventional procedures or conservative treatments other than analgesic medications for managing pain were also assessed. Any complications associated with the ITMP, including constipation, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, dizziness, dry mouth, and diaphoresis, were thoroughly reviewed. The patients' overall satisfaction following ITMP implantation was surveyed at 1 year via a phone call and rated on a five-point Likert scale from “extremely satisfied” to “extremely dissatisfied.” We then surveyed the patients regarding their overall recommendations to improve the device.

2. Cost categories and calculations

Financial information was obtained from the Data Processing Department (DPD) and Insurance Review Department (IRD) of SNUH. In addition, the IRD provided data about each participant's type of insurance coverage. Actual payments for the entire medical services for 6 months before ITMP implantation, consistent with the reimbursement policy of the NHI program, and for 1 year after implantation, were calculated. Payments for medical services performed at facilities other than SNUH were not included in this study. Average medication costs (e.g., oral medication and patches) were investigated at three pharmacies close to SNUH.

The DPD provided the actual costs paid by each patient before, during, and after ITMP implantation, which included the costs for all medical services performed at SNUH. The total cost prior to ITMP implantation included the costs of medical services, interventions, procedures, and medications for 6 months before ITMP implantation. The total cost after ITMP implantation included outpatient medical costs, analgesics for breakthrough pain, and ITMP refills for 1 year after ITMP implantation. With regard to the total implantation cost, each patient's actual payment for the ITMP implantation procedure, including hospitalization, was calculated. The total cost of medical services during the treatment period, expressed in Korean Won (KRW)/day, was divided into pre- and post-ITMP implantation segments to determine the financial break-even point.

3. Statistical analyses

Wilcoxon's signed-rank test was used to compare NRS scores before and after ITMP implantation. The daily costs, before and after ITMP implantation, were compared. The monthly median cost of analgesic treatment after ITMP implantation was determined for all patients and compared with the projected monthly median cost before ITMP implantation. Each patient's total payment of medical costs for ITMP implantation, divided by the difference between the costs per day before and after ITMP implantation, was used to define the financial break-even point. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The data are expressed as median values [75% interquartile range (IQR)]. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance.

Go to :

RESULTS

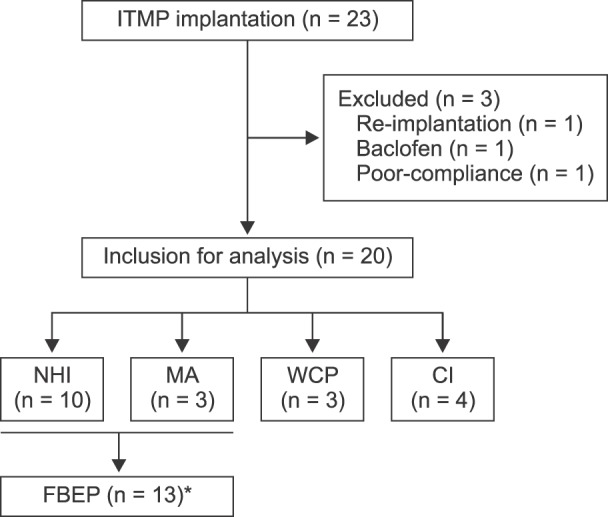

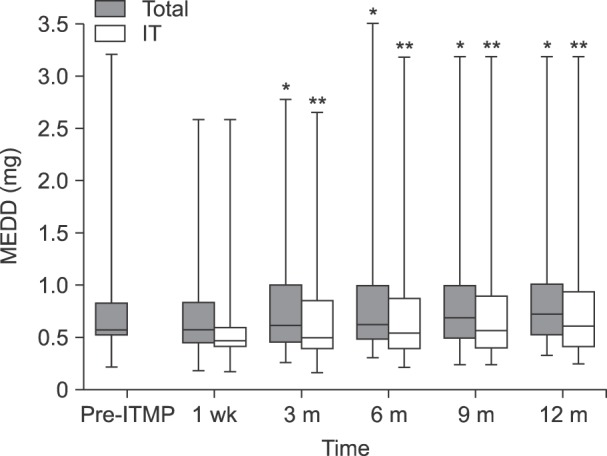

Twenty-three patients received ITMP implantation with a Medtronic SynchroMed II® pump (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) at SNUH between July 2014 and May 2016 (

Fig. 1). All surgical procedures for ITMP implantation were performed by one pain specialist.

| Fig. 1Flowchart. NHI: national health insurance, MA: medical aid, WCP: worker's compensation plans, CI: car insurance, FBEP: financial break-even point. *Thirteen patients that received 50% benefits from the new NHI policy were included to calculate the financial break-even point.

|

Three patients were excluded from the study for the following reasons: one patient received IDD pump implantation with baclofen, one patient received a replacement IDD pump following the first IDD pump implantation in 2008, and one patient was mainly managed at another hospital and only visited SNUH for ITMP treatment. Therefore, 20 patients were included in the study.

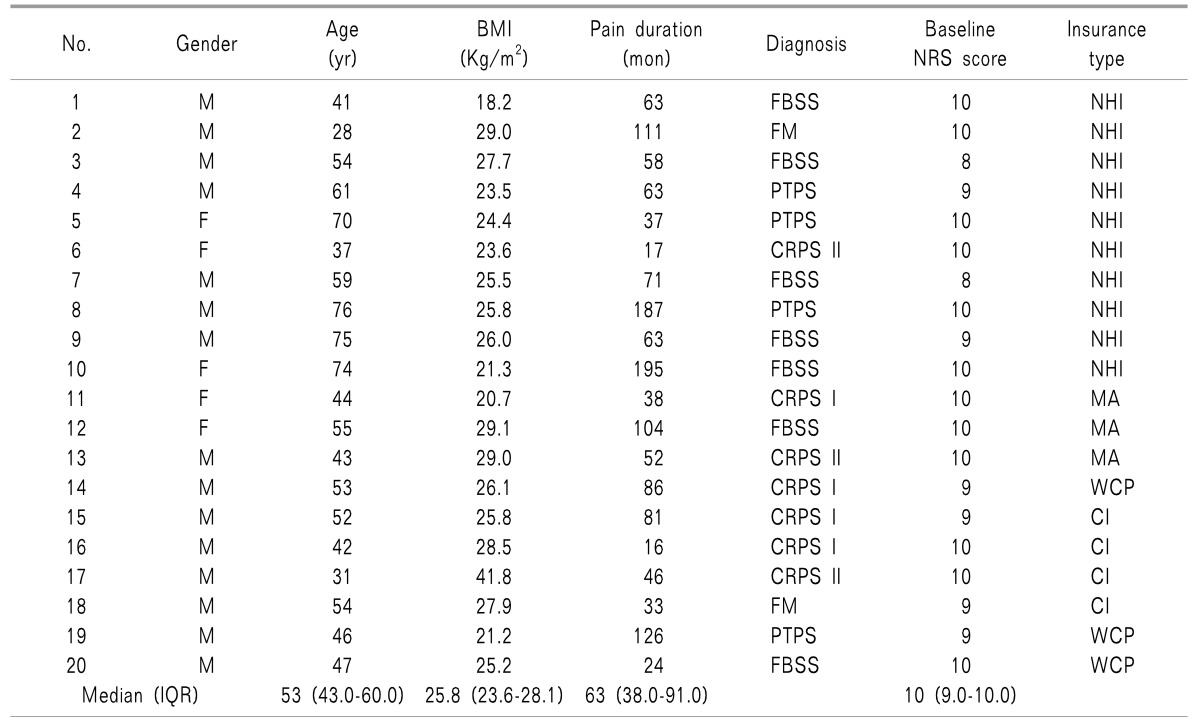

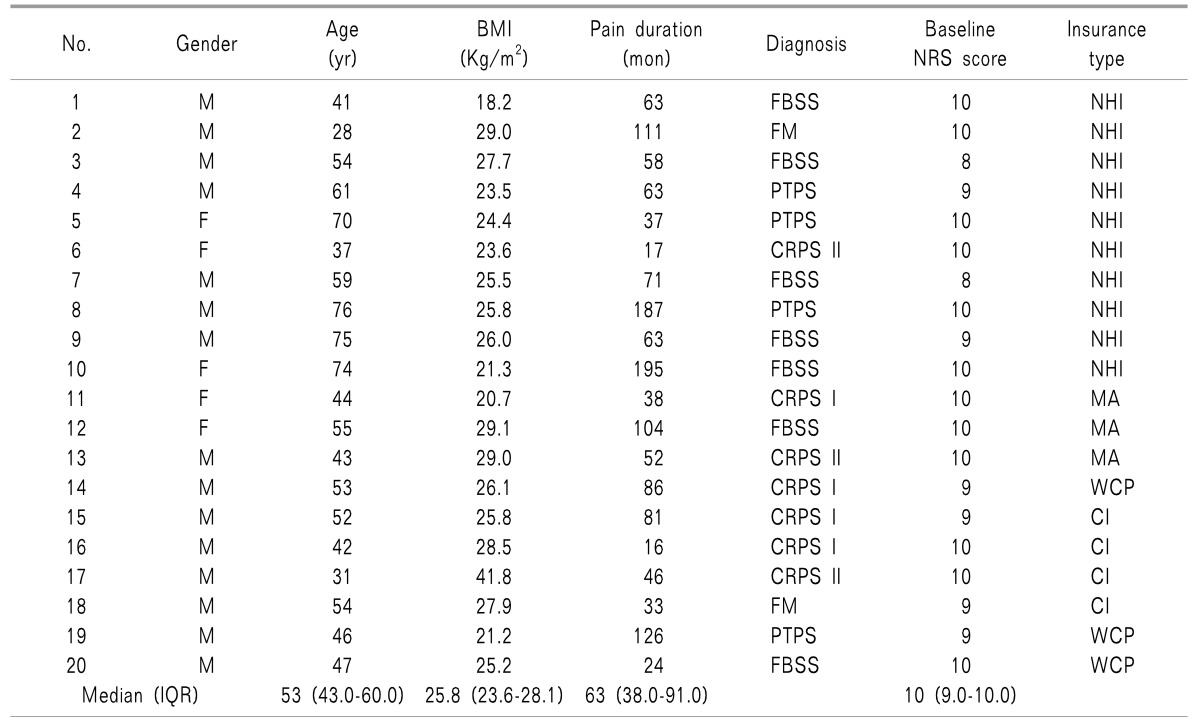

The demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in

Table 1. All patients were implanted with ITMP for the management of chronic non-cancer pain. The most common diagnoses for ITMP therapy in patients with chronic non-cancer pain were complex regional pain syndrome (n = 7) and failed back surgery syndrome (n = 7), followed by fibromyalgia (n = 2), and post-traumatic pain syndrome (n = 4). The median pain duration before ITMP implantation was 63 months [IQR: 38–91].

Table 1

Demographics

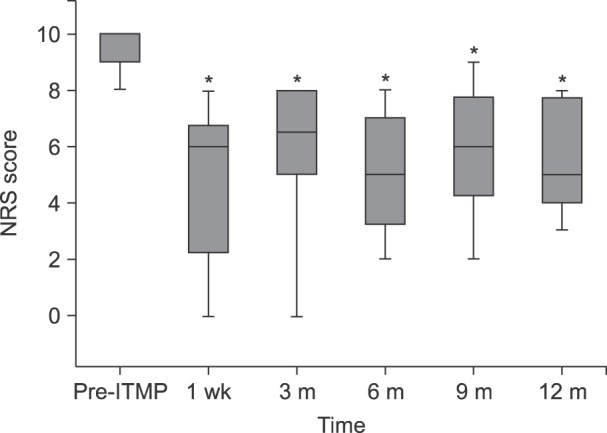

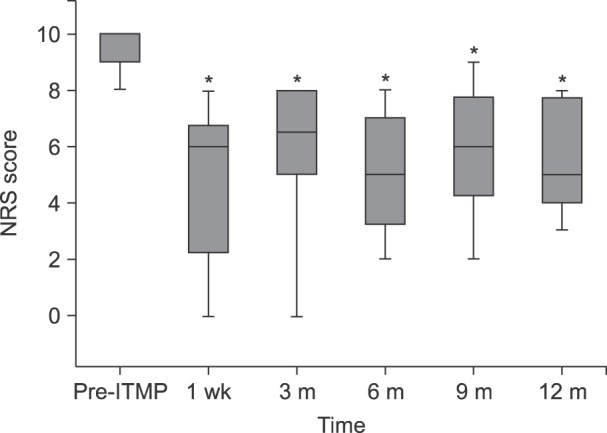

Fig. 2 shows the changes in the 11-point NRS pain score between pre- and post-implantation. The baseline median NRS pain score was 10 and ranged between 8 and 10. The value decreased to within the range of 0 to 8 with a median score of 6 at 1 week; all patients (n = 20) responded that their pain had decreased by more than 2 of 10 points after ITMP implantation. Although the NRS pain score increased steadily for 1 year after ITMP implantation, the median NRS pain score was still reduced relative to the baseline at 12 months, with a median score of 5, ranging from 3 to 8. Eighteen patients (90%) still showed a reduction of ≥ 2 points in their NRS score at 1 year. The NRS pain scores at each follow-up point were significantly reduced compared to the baseline value before ITMP implantation (

P < 0.001 between the baseline score and score at each follow-up point).

| Fig. 2NRS pain scores from pre-implantation to 12 months after transplantation. The box plot shows a set of three quartiles and the maximum and minimum graphically. At Pre-ITMP and 3 months, the maxima are not displayed because they were same as the median 3rd quartile and the 3rd quartile, respectively. NRS: numerical rating scale, ITMP: intrathecal morphine pump. *Statistically significant difference between the time point and Pre-ITPM (P < 0.05).

|

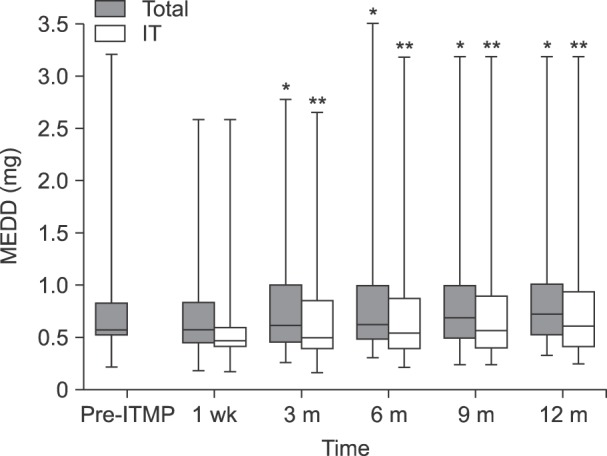

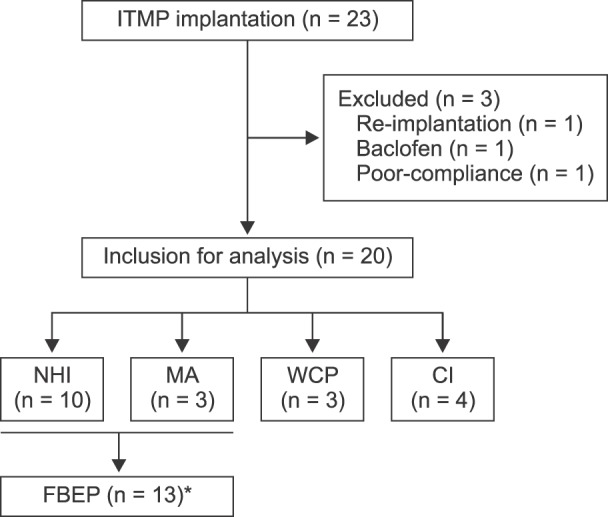

The median IT MEDD before ITMP implantation was 0.59 [IQR: 0.55–0.82] (

Fig. 3). The median initial setting of IT dosage via ITMP was 0.47 mg/day [IQR: 0.44–0.65], which was 70%–90% of the previous MEDD in each case at the discretion of the physician. In addition, patients received a concurrent immediate release form of opioid; therefore, the total MEDD at 1-week follow-up, calculated as IT administration was 0.61 [IQR: 0.46–0.82]. Throughout the follow-up period, the MEDD was increased steadily to 0.60 [IQR: 0.47–0.88] as IT administration via ITMP and 0.77 [IQR: 0.53–1.08] at 1 year as the total MEDD, representing a 126% of baseline (

P < 0.001 for both IT and total administration).

| Fig. 3Daily intrathecal morphine equivalent drug doses at various time points. “Total” indicates the total dose of morphine equivalent drug each patient took daily every 3 months. “IT” indicates the amount of morphine administered per day via ITMP. Pre-ITMP, opioid dose calculated as the equivalent intrathecal morphine dose before ITMP implantation. Post-ITMP, opioid dose calculated as the equivalent intrathecal morphine dose after ITMP implantation. We investigated every 3 months for 1 year from the start of treatment. IT: intrathecal, ITMP: intrathecal morphine pump, MEDD: morphine equivalent daily dose. *Statistically significant difference between the initial IT morphine dose and each time point (P < 0.001). **Statistically significant difference between the total IT morphine dose as the initial setting and each time point (P < 0.001).

|

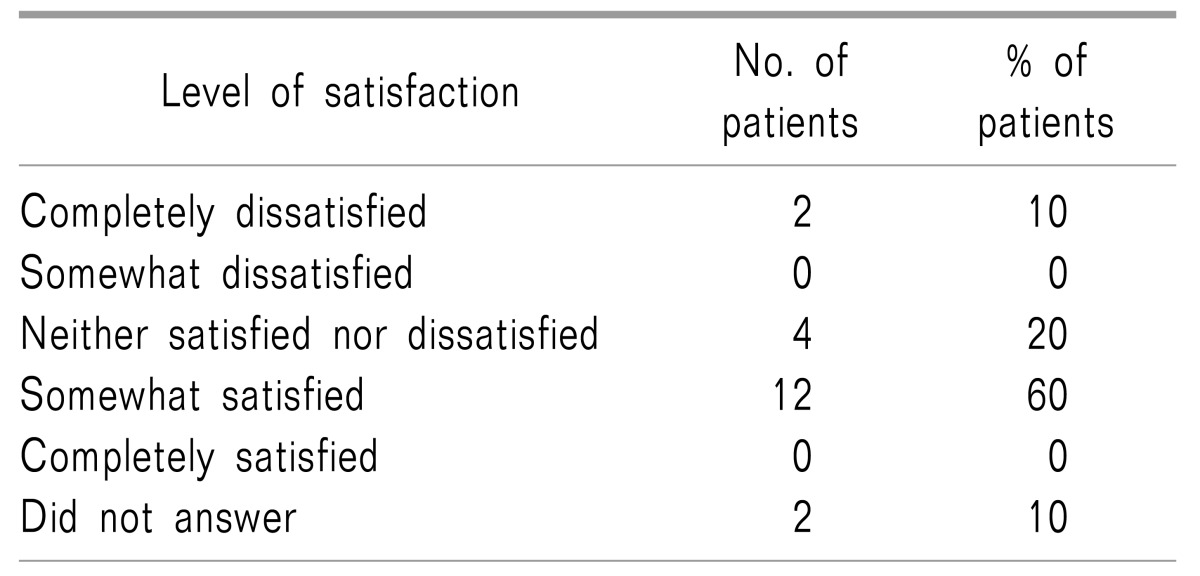

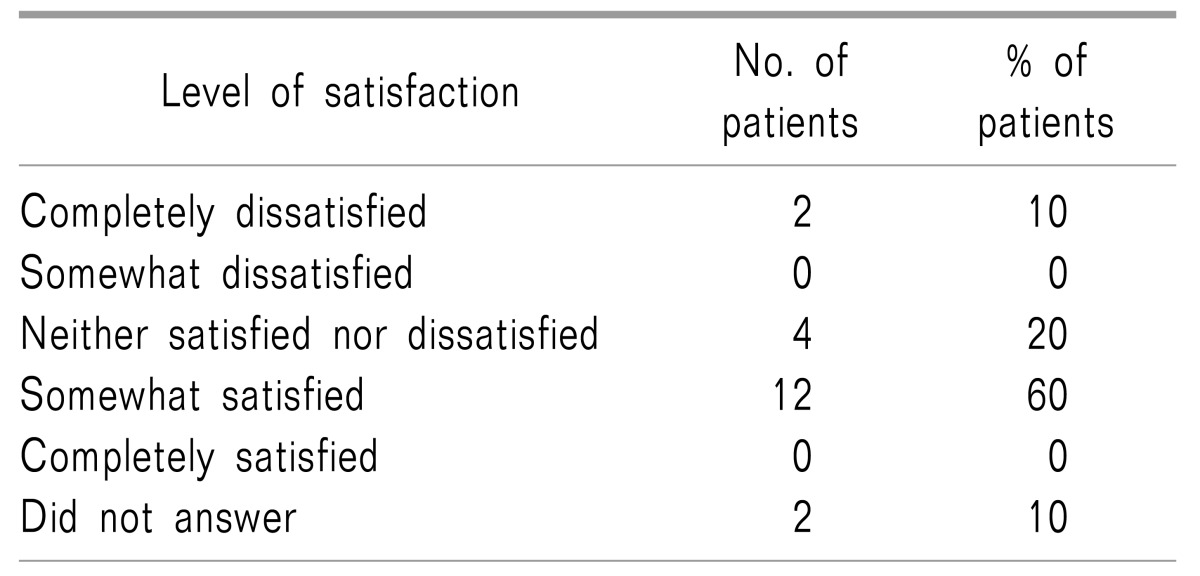

The 20 patients included in the analysis were surveyed by an in-person phone call and asked about their overall satisfaction after the ITMP implantation treatment using a 5-point Likert scale. Twelve patients (60%) responded that it was somewhat satisfying, four patients (20%) responded that they were “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” with ITMP management, two patients (10%) were “completely dissatisfied,” and two patients refused to answer the question (

Table 2). Patients that were “completely dissatisfied” also complained of severe worsening of pain accompanied by neuropsychiatric panic disorders such as panic or depressive disorders. Nonetheless, all patients agreed that the frequency and intensity of their pain had been alleviated. Sixteen patients (80%) also agreed that the ITMP helped to control pain. Finally, when we surveyed patients about their recommendations to improve the device, most patients (n = 16, 80%) suggested that a reduction in the pump reservoir size and the acquisition of a controlling device for self-infusion (patient-controlled analgesia) would improve general satisfaction and pain control. A personal therapy manager (myPTM™; Medtronic, Inc.) was not available before November 2016 in South Korea.

Table 2

Overall Satisfaction after ITMP Implantation Treatment Using a 5-point Likert Scale

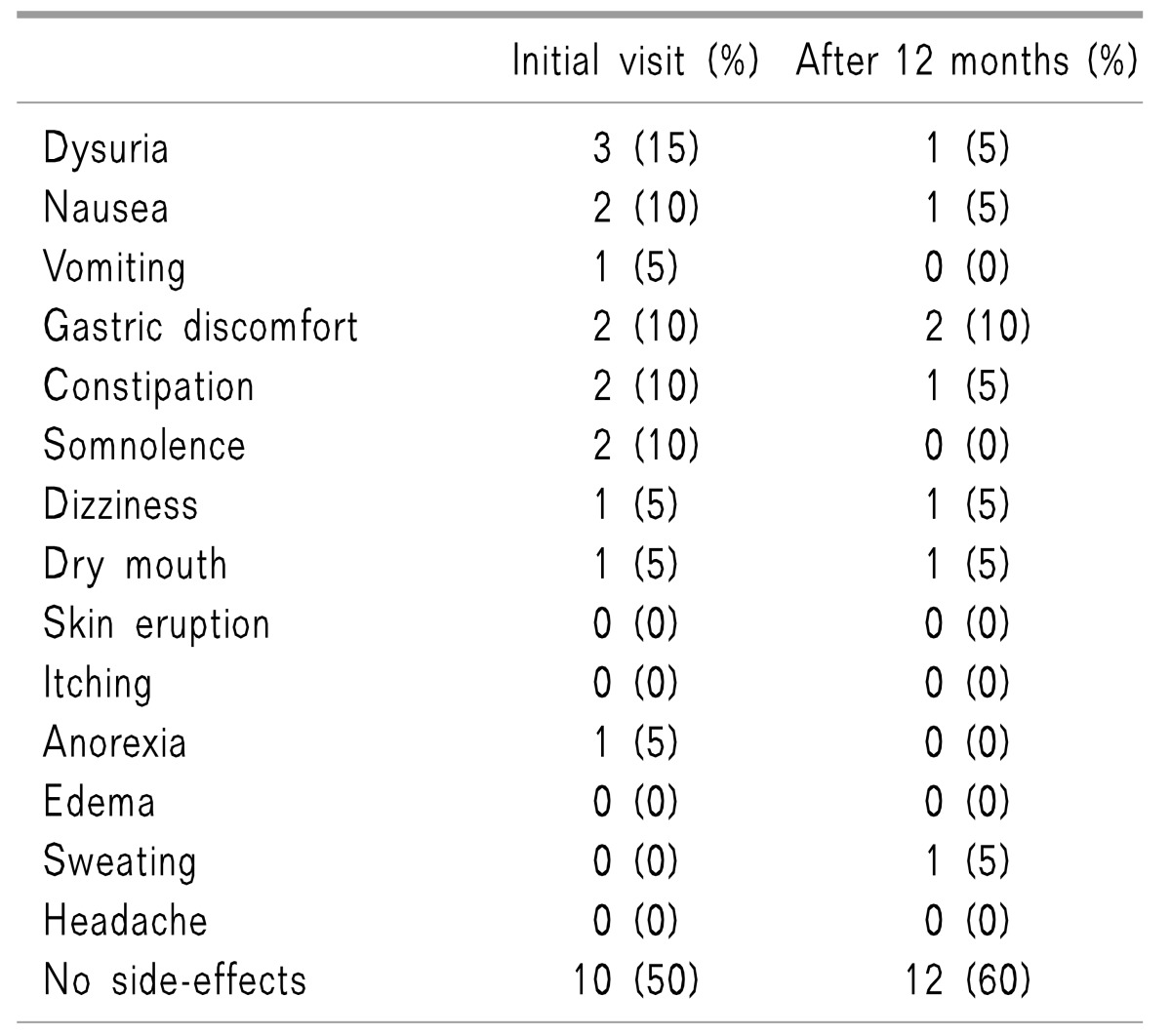

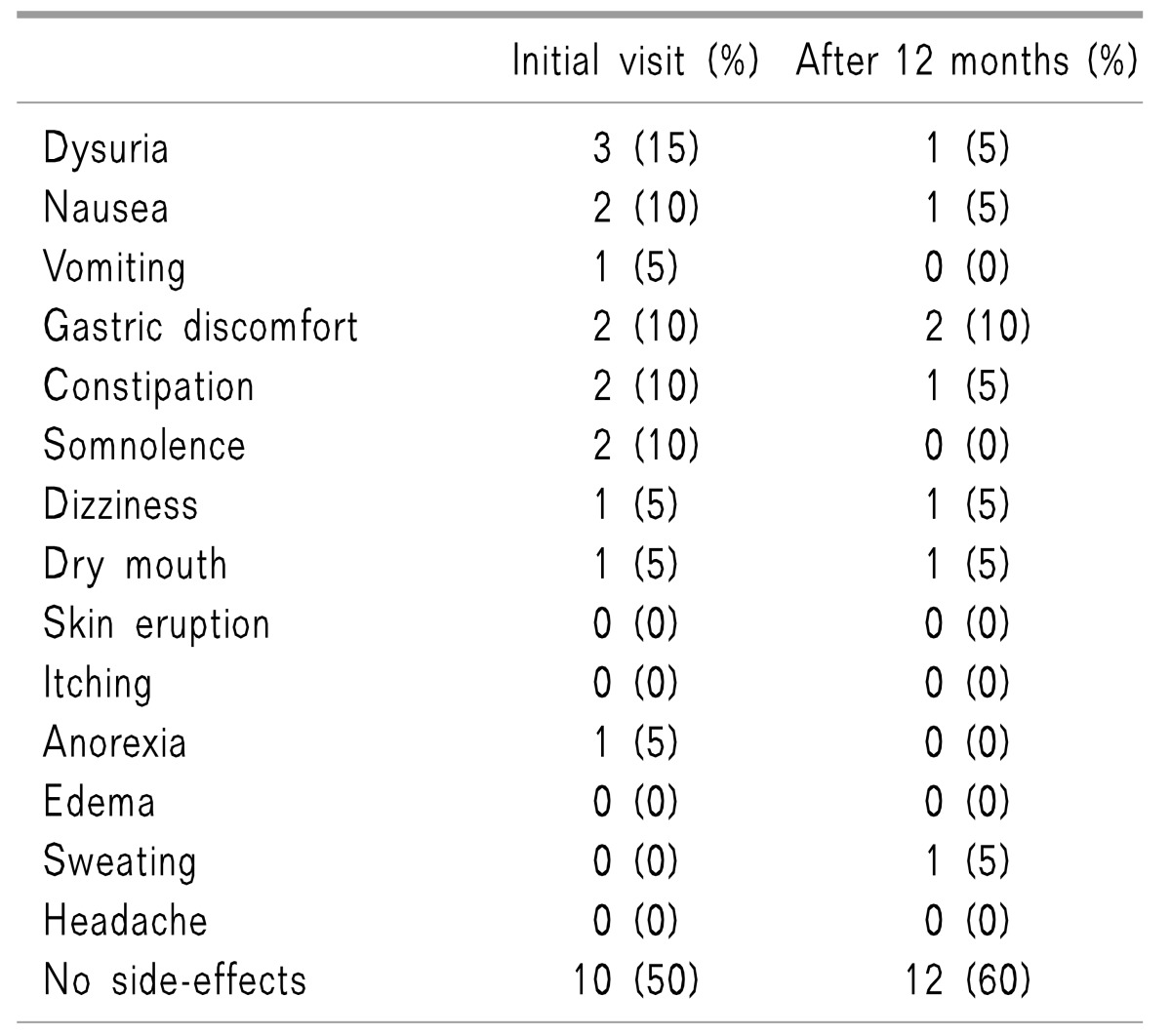

The side effects observed after ITMP implantation are shown in

Table 3. At 1 week after ITMP implantation, half of the patients reported one or more adverse events associated with ITMP implantation; dysuria (n = 3) was the most frequent event, followed by nausea, vomiting, and gastric discomfort. Ten patients reported that they had not experienced any adverse events related to ITMP. At 1 year, twelve patients were free from opioid-related side effects.

Table 3

Adverse Events Observed after ITMP Implantation

To calculate the financial break-even point, we investigated each patient's reimbursement insurance status (shown in

Table 1). Among the 20 patients in this study, 10 (50%) were reimbursed by NHI coverage. Three patients (15%) were under Medical Aid (MA) as an extension of the NHI program for minorities. Among the remainder, three patients were covered by Worker's Compensation Plan Insurance (WCPI) and four patients were under Car Insurance (CI) coverage. NHI paid 50% of ITMP costs and MA covered 50% of ITMP costs and partial professional fees. WCPI and CI covered 100% of ITMP costs. The actual total ITMP cost of the patient's share of medical costs differed markedly according to the type of insurance, and ranged from 0 to 8,580,000 KRW. Therefore, to estimate the financial break-even point, we included only thirteen patients in the study who paid for 50% of their actual ITMP costs; ten were covered by NHI and three had MA coverage.

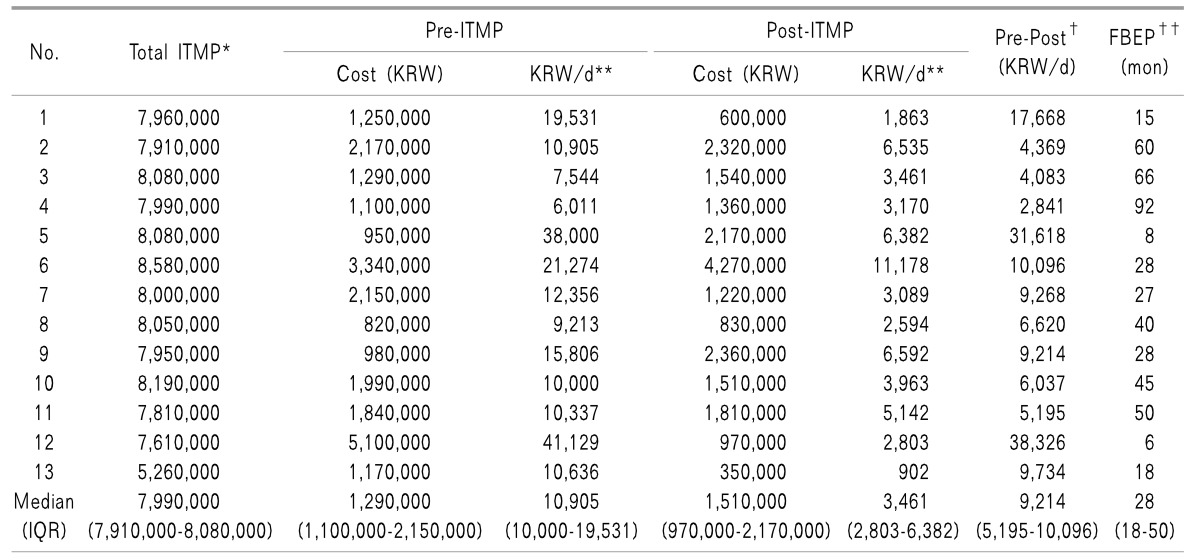

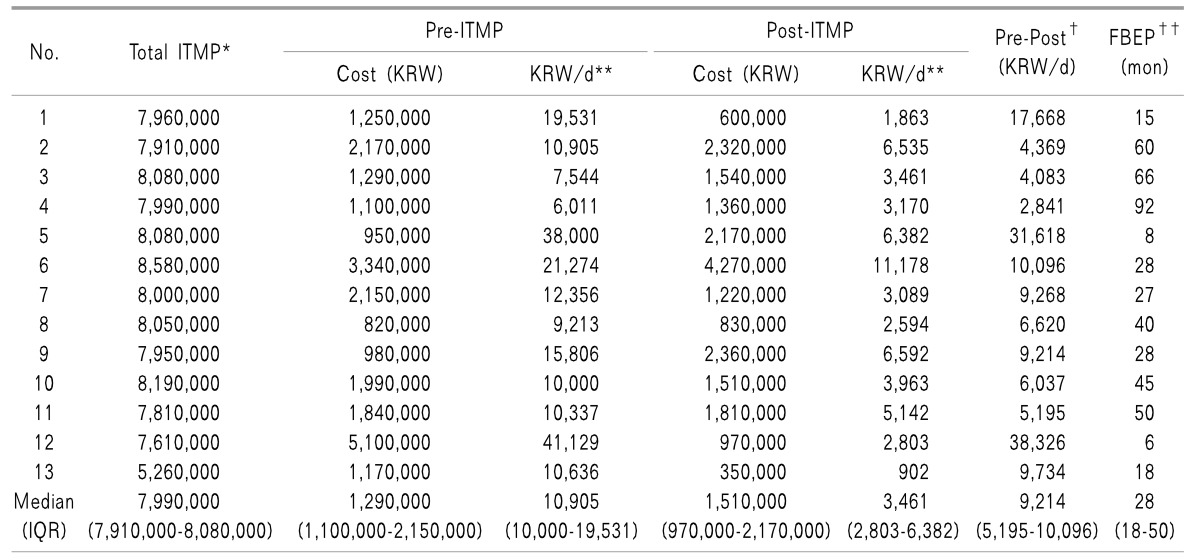

Their financial break-even points are shown in

Table 4. Their pre-implantation medical costs ranged between 6,011 and 41,129 KRW/day (median: 10,905 KRW/day). The post-implantation medical cost per day ranged between 902 and 11,178 KRW/day (median: 3,461 KRW/day). Our data show that a period of 28 months was required to reach the financial break-even point following ITMP implantation treatment.

Table 4

Analysis of the Cost Effectiveness of ITMP Treatment

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Chronic pain is acknowledged as a condition in its own right that results in both physical and emotional burdens on patients as well as a huge financial cost to society (currently estimated at more than €200 billion per annum in Europe and $150 billion per annum in the USA) [

14]. Economic and reimbursement difficulties continue to constrain the use of advanced therapies such as IDD pump implantation for chronic pain patients [

11]. Studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of IDD pump implantation may encourage organizations to reduce costs or to increase health insurance coverage, and it may promote the use of this expensive therapy. Therefore, we performed a retrospective study to analyze the influence of Korea's reimbursement policy, adopted in 2014, with regard to the financial break-even point for was determined was determined the ITMP in chronic non-cancer pain patients at SNUH, trends in patient access to this treatment, and patients' overall satisfaction.

With regard to the efficacy of the ITMP, 90% (n = 18) of the patients in our study showed a reduction of ≥ 2 points in their NRS score at 1 year after ITMP implantation, and the other two patients showed a decrease of 1 point in their NRS score compared to the pre-implantation score. Although the results of previous studies were contradictory with regard to the efficacy of IDD use in chronic non-cancer and cancer pain patients, recent research by Hamza et al. strengthened the positive results reported for ITMP treatment (94% of non-malignant pain patients showed > 26% improvement in their pain score compared with the baseline) [

15]. In our study, we also found a reduction in NRS score at the initial and final follow-up visits compared to the baseline score before ITMP implantation. We suggest that appropriate patient selection is the key to a successful outcome following ITMP treatment [

16].

Increasing IT opioid administration, which was reported in previous studies, indicates that dose escalation may be independent of the opioid delivery method over the long term [

17181920]. In this study, the increase in median ITM dosage was 126% at the first year of follow-up compared to the initial ITM dosage. This rate of increase was relatively low compared to those suggested in a systematic review by Turner et al., which indicated a 2.6–7.4-fold increase in IT opioid dosage from initial levels at 24 months [

17]. However, this was similar to the results of our previous study performed at the same hospital indicating that the ITM dose escalation was 136.9% during the first year [

12]. We assume that a lower initial ITM dose may have been related to the decreased ITM escalation rate in our study, which may support previous studies suggesting that using a low-dose IT opioid trailing method had clinical benefit as an effective dosing strategy [

2122].

With regard to satisfaction with ITMP treatment, 60% of patients were “somewhat satisfied” with their ITMP therapy. This was an improvement in comparison with our previous study that showed that only 41% of patients were “somewhat satisfied” prior to NHI reimbursement [

12]. Although, 20% of the patients in our study responded that they were “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” and 10% did not respond, all patients agreed that the frequency and intensity of their pain had been decreased and eased. The large size of the pump was one of the main issues to be addressed in the future. Patients generally felt uncomfortable with the pump device when wearing thin clothes, while lying down, or sitting straight. Therefore, future ITMP development should include reducing the size of the device.

Prior to July 2014, Korean patients were required to pay all costs related to ITMP implantation with their own money. However, since the Korean reimbursement system was announced in July 2014, 50% of ITMP costs can be reimbursed to patients that fulfill the established criteria of the NHI program. This implies a huge economic benefit to patients considering ITMP treatment; however, there may be concerns about the inappropriate application or ITMP treatment, such as misuse or abuse, so it may result in unmet cost-effectiveness. In the present study, when patients paid their medical costs using NHI coverage, it took 28 months to obtain a financial advantage. Although this is somewhat longer than the period of 24.2 months that we reported in a previous study without NHI coverage [

12], it is still worthwhile when taking into account that the median longevity of patients with ITMP use is 5.4 years (95% confidence interval: 5.0–5.8) [

2]. Studies in the USA have reported cost-effectiveness data for ITMP treatment, with a diverse range from 7.6 months in cancer patients to 22 months for patients with non-malignant pain [

23]. As we did not administer the concept of quality-adjusted life years in our analysis of cost effectiveness and did not include costs paid to other hospitals, it is not possible to compare our results with previous cost-effectiveness data. However, when we consider that the overall medical service fee is much cheaper in Korea than in the USA, and if we reflect on the benefits from the improvement in quality of life, the financial break-even point of 28 months in our study is not excessive.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective study, and our results may have been affected by characteristic confounders, including bias and variability in the quality of available information. Second, as mentioned previously, the concept of improvement in quality of life was not administered in our analysis. Furthermore, we did not include pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical treatment costs at other institutions. These may reduce the time needed for the financial breakeven point, which was suggested in this study as 28 months. Finally, this was a single-center study with a limited number of patients, which would result in several biases related to patient selection for ITMP treatment or other medical costs. Future prospective large cohort studies should attempt to validate the cost effectiveness of ITMP therapy.

In conclusion, ITMP provided effective chronic pain management with overall improved satisfaction and fewer systemic adverse events in our study. The financial breakeven point was 28 months in patients with 50% coverage of their medical cost for ITMP implantation by the NHI program. When we, as pain physicians, consider the application of ITMP therapy for the management of intractable chronic cancer or non-cancer pain, attention should be paid to appropriate patient selection as well as their clinical improvement and economic benefits. Additional studies are required to improve patients' pain and analyze the cost effectiveness of ITMP management.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download