Abstract

Background

Spinal pain is most common symptom in pain clinic. In most cases, before the treatment of spinal pain, physician explains the patient's disease and treatment. We investigated patient's satisfaction and physician's explanation related to treatments in spinal pain patients by questionnaires.

Methods

Anonymous questionnaires about physician's explanation and patient's satisfaction in each treatment and post-treatment management were asked to individuals suffering from spinal pain. Patients who have spinal pain were participated in our survey of nationwide university hospitals in Korea. The relationships between patient's satisfaction and other factors were analyzed.

Results

Between June 2016 and August 2016, 1007 patients in 37 university hospitals completed the questionnaire. In the statistical analysis, patient's satisfaction of treatment increased when pain severity was low or received sufficient preceding explanation about nerve block and medication (P < 0.01). Sufficient explanation increased patient's necessity of a post-treatment management and patients' performance rate of post-treatment management (P < 0.01).

Go to :

Most people experience spinal pain, such as neck or low back pain (LBP), during their lifetime [1]. The lifetime prevalence of neck pain is approximately 50% [2]. The lifetime prevalence of low back pain is 75-85% and the yearly recurrence rate is as high as 60% [34]. Low back pain is the second most common reason for visits to a physician, the fifth most common cause of hospital admission, and the third most frequent cause of surgery [5].

There are many treatments such as medication, nerve block, physical therapy, and exercise for spinal pain. However, there has been little investigation of patients' satisfaction with these treatments. In most cases, doctors explain the patients' diagnosis and treatment procedure. Doctor-patient communication seems to have an influence on patients' behavior, satisfaction with care, adherence to treatment, recall, and understanding of medical information [6]. However, there has been little investigation into the relationship between the explanation of the treatment and patient satisfaction with spinal pain patients.

We investigated the relationship between physician explanations and patient satisfaction in regards to nerve blocks and medications, and between physician explanations and the performance rate of post-treatment management (exercise, weight control, correction of posture and so on).

Go to :

This investigation was a cross-sectional study of patients suffering from spinal pain. Between June 2016 and August 2016, we conducted a survey of patients who had spinal pain in 37 university hospitals in Korea. Patients with who had spinal pain were selected for participation by their doctors, who knew their symptoms and diagnoses. These patients participated in completing anonymous questionnaires in their outpatient pain clinic or hospital ward. Patients who did not want to answer the questionnaires were excluded in this investigation.

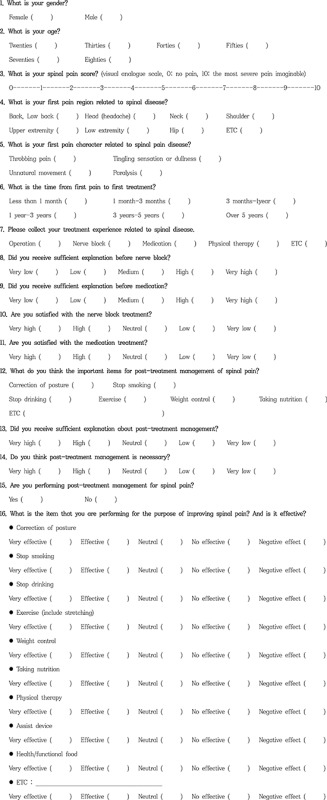

Anonymous questionnaires about physician explanations, patient satisfaction with each treatment, and the performance of post-treatment management were asked. The questionnaires consisted of 16 questions including gender, age, pain severity, initial pain site, time elapsed before initiating treatment, character of the pain, the patient's satisfaction rate with nerve blocks and medication, post-treatment management, and whether there was sufficient explanation about treatment and post-treatment management (Appendix 1).

The data was analyzed with SPSS version 17, using the Chi-square test, student t-test, and logistic regression analysis. The proportional differences, such as gender, were evaluated using the Chi-square test. The mean differences such as age, pain severity, elapsed time from the first pain symptoms to the first treatment, and whether or not they had received sufficient explanation were analyzed using a student t-test. To evaluate what factors affected the patient's satisfaction with treatments and the performance of post-treatment management, the respondents were divided into two groups, such as the satisfaction group vs. the dissatisfaction group, in regards to treatments (in these groups, the patients who answered neutrally were excluded), or the performance group vs. the non-performance group in post-treatment management. Before logistic regression analysis, using the Chi-square test and student t-test, we found the factors of P < 0.1 between the groups. Then, these factors were analyzed by logistic regression analysis. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Go to :

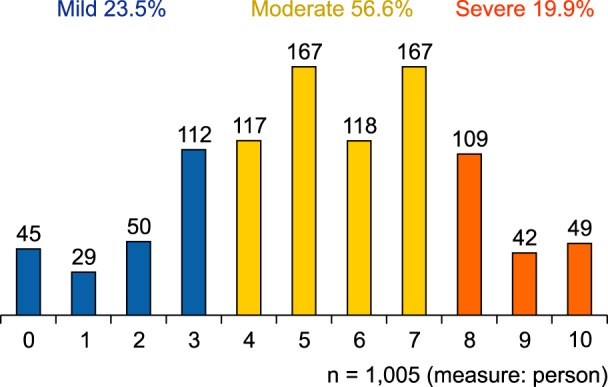

In 37 university hospitals, 1007 patients answered the questionnaires. This number included 600 (59.6%) females and 407 (40.4%) males. The survey respondent's ages included 51 (5.1%) in their twenties, 123 (12.2%) in their thirties, 130 (12.9%) in their forties, 227 (22.5%) in their fifties, 246 (24.4%) in their sixties, 166 (16.5%) in their seventies, and 61 (6.1%) in their eighties. Two hundred and thirty-six (23.5%) out of 1005 (excluding 2 non-respondent) had spinal pain between visual analogue scale (VAS, 0: no pain, 10: the most severe pain imaginable) 0-3, 569 (56.6%) respondents were between VAS 4 and 7, and 200 (19.9%) respondents were over VAS 8. The mean score on the VAS was 5.4 (standard deviation: 2.5) and distribution of VAS scores is described in Fig. 1.

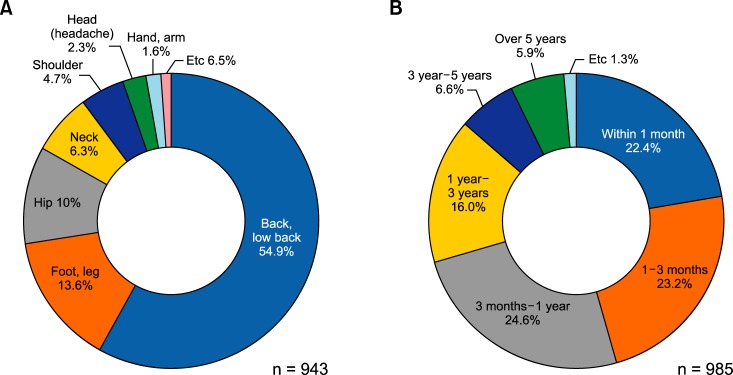

Among 943 respondents (excluding 64 non-respondent), the initial pain site was located on the back of the spine in 518 (54.9%) respondents, a lower extremity in 128 (13.6%) respondents, and the hip in 95 (10%) respondents (Fig. 2). Among 988 responses (multiple responses), the first pain character was throbbing pain in 511 (51.7%) respondents, a tingling sensation or dullness in 421 (42.6%) respondents, unnatural movement in 280 (28.3%) respondents, and paralysis in 49 (5%) respondents. Among 985 respondents, the time from their first pain to the first treatment was within three months in 450 (45.6%) respondents, and after 1 year in 281 (28.5%) respondents (Fig. 2).

Among 972 respondents (excluding 35 non-respondent), 477 respondents received a nerve block. Among 464 respondents (excluding 13 non-respondents), 228 (47.4%) were satisfied with the nerve block, 168 (39.5%) were neutral, and 68 (13.1%) were dissatisfied.

Among 972 respondents (excluding 35 non-respondents), 649 took medication. Among 611 respondents (excluding 38 non-respondents), 194 (31.9%) were satisfied with their medication treatment, 315 (51.8%) were neutral, and 102 (16.3%) were dissatisfied.

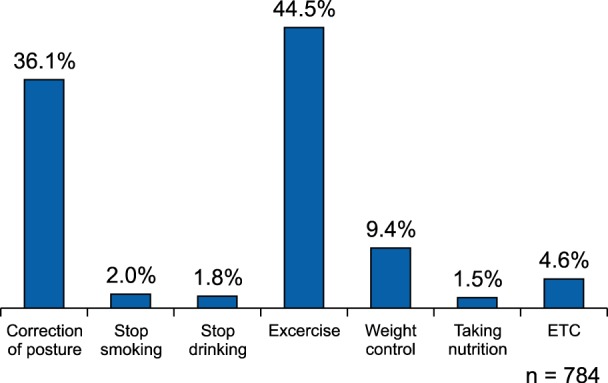

Eight hundred thirteen (82.8%) out of 982 respondents (excluding 25 non-respondents) thought that post-treatment management was necessary. Stretching and exercising was considered the most important post-treatment management by 349 (44.5%) out of 784 respondents (excluding 223 non-respondents), correcting posture by 283 (36.1%) respondents, and weight control by 74 (9.45%) respondents (Fig. 3).

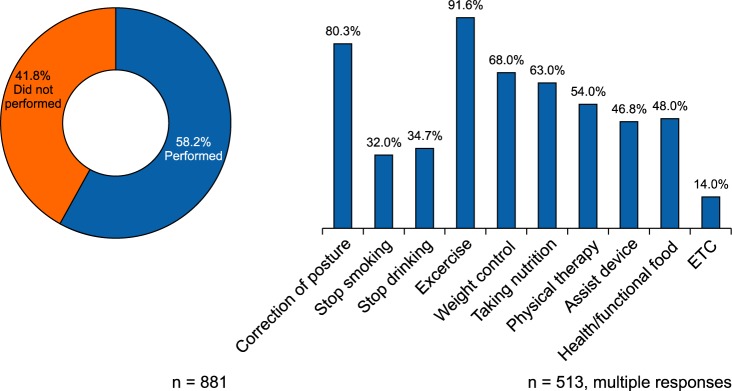

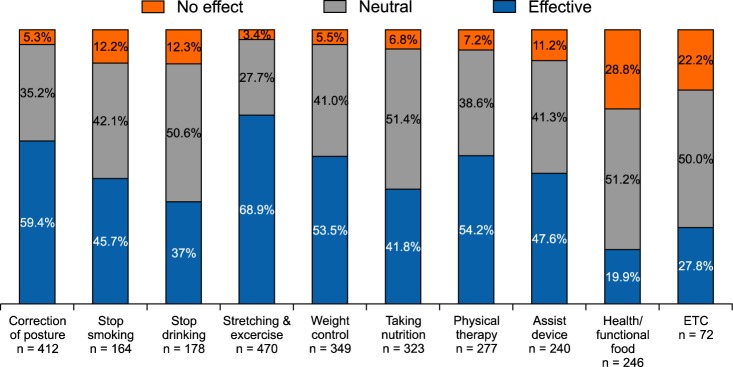

Five hundred twelve (58.2%) out of 881 respondents had performed post-treatment management. Four hundred thirty (91.6%) out of 470 respondents took exercise, 331 (80.3%) out of 412 respondents worked on correcting their posture, and 237 out of 349 (68%) tried to control their weight (Fig. 4). Three hundred twenty-four out of 470 (68.9%) respondents answered that exercise was effective, 245 out of 412 (59.5%) answered that correct posture was effective, and 187 out of 349 (53.6%) answered that weight control was effective. The effectiveness of the items performed in post-treatment management is described Fig. 5. The item that was thought to be the most effective for post-treatment management by patients was exercise, and item that was considered the least effective in its effects for post-treatment management by patients was healthy and functional food.

One hundred ten (11.2%) out of 979 respondents (excluding 28 non-respondents) answered that they did not receive sufficient preceding explanation about post-treatment management.

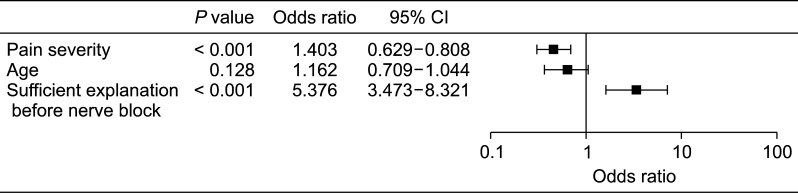

In comparing the satisfaction group (228 out of 464) and the dissatisfaction group (68 out of 464) after nerve blocks, gender (P = 0.881 in χ2 test) and the time from first pain to first treatment (P = 0.314 in student t-test) were not significantly different. Age (P < 0.001), low pain severity (P < 0.001), and sufficient explanation before the procedure (P < 0.001) were the factors of P < 0.1 using the student t-test. Age, pain severity, and sufficient explanation before the procedure were analyzed by logistic regression. After the analysis, pain severity (OR = 1.403, 95% CI = [0.629-0.808], P < 0.001), and sufficient explanation before the procedure (OR = 5.376, 95% CI = [3.473-8.321], P < 0.001) were related to patient's satisfaction with the nerve block. However, age was not related to the patient's satisfaction with the nerve block (P = 0.128) (Fig. 6).

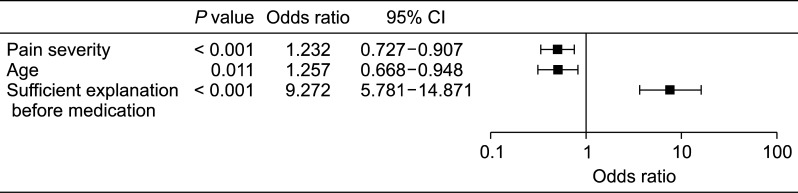

In comparison between the satisfaction group (183 out of 611) and the dissatisfaction group (102 out of 611) after medication, gender (P = 0.978 in χ2 test) and the time from first pain to first treatment (P = 0.636, student t-test) were not significantly different. Age (P = 0.001), low pain severity (P < 0.001), and sufficient explanation before the medication (P < 0.001) were the factors of P < 0.1 using the student t-test. Age, pain severity, and sufficient explanation before medication were analyzed by logistic regression. After the analysis, age (OR = 1.257, 95% CI = [0.668-0.948], P = 0.011), pain severity (OR = 1.232, 95% CI = [0.727-0.907], P < 0.001), and sufficient explanation (OR = 9.272, 95% CI = [5.781-14.871], P < 0.001) were related to patient's satisfaction with medication (Fig. 7).

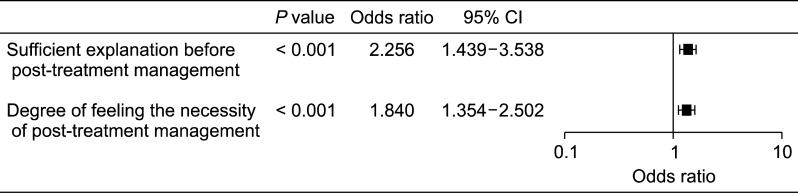

In the survey that investigated the correlation between performance of post-treatment management and other items such as gender, age, pain severity, sufficient explanation before post-treatment management, and degree of feeling the necessity of post-treatment management. Gender (P = 0.447 in χ2 test) was not significantly different. Age (P = 0.232), and pain severity (P = 0.118) were also not significantly different using the student t-test. Sufficient explanation before post-treatment management (P < 0.001) and degree of feeling the necessity of post-treatment management (P < 0.001) were the factors of P < 0.1 using the student t-test. Sufficient explanation before post-treatment management and degree of feeling the necessity of post-treatment management were evaluated by logistic regression. After the analysis, sufficient explanation before post-treatment management (OR = 2.256, 95% CI = [1.439-3.538], P < 0.001), and degree of feeling the necessity of post-treatment management (OR = 1.840, 95% CI = [1.354-2.502], P < 0.001) were related to performance of post-treatment management (Fig. 8).

In comparing the sufficient explanation group and insufficient explanation group in regard to post-treatment management, the necessity of post-treatment management in the sufficient explanation group was higher than that in the insufficient explanation group (P < 0.001).

Go to :

The data from 37 university hospitals were obtained from almost all the university hospitals in Korea. In the results, 76.5% of patients had moderate to severe spinal pain. However, only 46% of patients started treatment within 3 months from their first symptom. Twenty-eight and five tenths percent of patients started treatment after over 1 year from their first symptom. This suggested that many people with spinal pain did not go to hospital at an early stage, or that when their pain got worse, they then visited the hospital. Delay in seeking treatment for spinal pain can bring about the delayed diagnosis of serious disorders or chronic neuropathic pain.

There are several studies that show that early interventional treatment such as the epidural block is more effective than late treatment [78910]. Peripheral and central sensitization in chronic pain can cause intractable pain [11]. In patients with chronic pain, they can have a combination of neuropathic characteristics. In 2006, Torrance et al. [12] reported that the overall prevalence rate of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics was 8.2% in the UK. In 2008, Bouhassira et al. [13] reported that 1,631 respondents out of 7522 respondents (21.7%) with chronic pain had neuropathic characteristics in France. Early treatment may decrease the exacerbation of disease and progression of combined neuropathic pain.

Chronic spinal pain can also cause other symptoms such as insomnia and depression [1415]. In a previous study, a major depressive disorder was related to chronic spinal pain [16]. Kim et al. [15] reported that 20% of patients with chronic low back pain, in their study, had clinically significant insomnia. And they found that high pain intensity, the presence of comorbid neuropathic pain components, and depression level were strongly associated with clinical insomnia [15].

According to those receiving nerve blocks and medication, sufficient explanation of the treatments increased the patient's satisfaction. Patients who received sufficient explanation of post-treatment management also performed the management at a high rate. To increase patients' satisfaction with treatment and performance rate in post-treatment management, physicians have to explain sufficiently about the treatment and the effect of the management on spinal pain. However, sufficient explanation requires enough time for the description of the management. If medical insurance rewards sufficient explanations, and allows enough time for the physician or hospital to make them, the satisfaction of the physician and patient will increase.

In the results, age was not related to the patient's satisfaction with nerve blocks in logistic regression analysis (P = 0.128). Nevertheless, age was related to patient's satisfaction with medication (95% CI = [1.055-1.497], P = 0.011). In other words, there were no significant differences according to age in treatment satisfaction after nerve blocks, but medication provided greater satisfaction in young patients than in elderly ones. This may be related to the limited doses and limited selection of drugs in old age, because a greater proportion of elderly patients have underlying diseases, and are taking various medications for them. Elderly patients also have substantial individual variability in health, disability, age-related changes, poly-morbidity, and associated poly-pharmacy [17]. Therefore, prescribing medicine requires meticulous care and can be difficult for a physician. However, to prove these hypotheses, further investigation will be required.

Pain severity was related to patients' satisfaction with medication and nerve blocks (Fig. 6 and 7). Patients with low-level pain intensity had greater satisfaction than patients with high level pain intensity. Patients with severe pain can have other combined symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and impaired sleep [1819]. Therefore, for the treatment of patients with severe pain, a multimodal approach and intensive treatment may be necessary. The patient's multiple problems can decrease their satisfaction with treatment.

When the quality of communication with the doctor is rated highly, patients are more likely to be satisfied with their medical care [20]. In previous investigations, the most frequent communication problems were inadequate explanation of diagnosis or treatment [21222324] and ignored patient feeling [222324]. Poor communication between the physician and the patient also could be a risk factor for malpractice suits Kim et al. [25] reported that pain in the lumbar region made up a major proportion of medical-dispute cases and compensation costs and good communication may decrease the likelihood of malpractice suits [26].

Most patients are not communicatively comfortable and competent enough to express their physical condition and feeling in everyday language. Especially, in Korean medical culture, a feeling of awe towards the doctor may exist in people's minds, and this fact itself becomes a major hindering factor for the effective communication between doctors and patients. Therefore, doctors who provide adequate explanations about management still need to overcome this hindering factor. Moreover, the gaps in knowledge about medicine between doctors and patients are wide. Most patients want to know exactly what their disease is and to understand its treatment [27]. Therefore, doctors' explanations can be important, and increase the patient's satisfaction.

In this investigation, sufficient explanation increases patient satisfaction with treatment, the degree of performance of the post-treatment management, and the degree of feeling the necessity of post-treatment management. This result also showed that the degree of feeling the necessity of post-treatment management is associated with performance of post-treatment management. Therefore, it seems that sufficient explanation improves the doctor-patient relationship and increases patient compliance in spinal pain patients.

In post-treatment management, many patients thought that exercise was the most important item. Exercise was also the most frequently performed post-treatment management in spinal pain patients. In a systematic review, van Tulder et al. [28] reported that exercise was as effective as conventional physiotherapy for chronic low back pain, and may be helpful for patients with chronic low back pain in returning to normal everyday life.

Ferreira et al. [29] also reported that a specific stabilization exercise produces modest beneficial effects for people with spinal and pelvic pain in their systematic review. However, if patients do not continue to exercise, the effectiveness will decrease. Therefore, motivation programs are positively necessary.

Friedrich et al. [30] reported that combined exercise and motivation programs were more effective than the standard exercise program. They used a motivation program that included extensive counseling, giving more information, positive feedback, and so on. Eighty-one and eight tenths percent of patients in the motivation group attended all of the physical therapy sessions, compared with 51% in the control group [30]. To motivate patients, enough explanation can be important, and this investigation can support the results of our study about the relationships between sufficient explanation and degree of feeling the necessity of post-treatment management, and between sufficient explanation and the performance of post-treatment management.

In this investigation, there are several limitations. First, because this survey was a cross-sectional study, we did not check the change in pain score and other items before and after treatments. Therefore, the improvement of pain score related to patients' satisfaction was not analyzed. Second, this survey did not contain other scales related to sufficient explanation such as time, use of figures, or contents of the explanation. There is a possibility that the satisfaction with the treatment may have been related to bias about sufficient explanation of the treatment. In future prospective investigations, the satisfaction with the explanation has to be investigated after the explanation, as well as after the procedure. However, in the questionnaires, we did not investigate the satisfaction with the explanation but rather the sufficiency of the explanation.

Therefore, we believe that the results can be meaningful for the relationship between sufficient explanation and treatment. Third, this survey did not differentiate between patients who received the treatment once and patients who received the treatment several times. The influence of repeated treatment and kinds of treatment for patient satisfaction were not analyzed. In the near future, investigation regarding these effects on patient satisfaction may be necessary.

These results show that sufficient explanation increased the patients' satisfaction after nerve blocks and medication. Sufficient explanation also increased patients' performance rate of post-treatment management.

Go to :

References

1. Gupta R, Singh S, Kaur S, Singh K, Aujla K. Correlation between epidurographic contrast flow patterns and clinical effectiveness in chronic lumbar discogenic radicular pain treated with epidural steroid injections via different approaches. Korean J Pain. 2014; 27:353–359. PMID: 25317285.

2. Fejer R, Kyvik KO, Hartvigsen J. The prevalence of neck pain in the world population: a systematic critical review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2006; 15:834–848. PMID: 15999284.

3. Kim EJ, Moon JY, Park KS, Yoo DH, Kim YC, Sim WS, et al. Epidural steroid injection in Korean pain physicians: a national survey. Korean J Pain. 2014; 27:35–42. PMID: 24478899.

4. Elfering A, Mannion AF. Boos N, Aebi M, editors. Epidemiology and risk factors of spinal disorders: fundamentals of diagnosis and treatment. Berlin: Springer;2008. p. 153–173.

5. Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999; 354:581–585. PMID: 10470716.

6. Smith CK, Polis E, Hadac RR. Characteristics of the initial medical interview associated with patient satisfaction and understanding. J Fam Pract. 1981; 12:283–288. PMID: 7462936.

7. Choi JW, Lim HW, Lee JY, Lee WI, Lee EK, Chang CH, et al. Effect of cervical interlaminar epidural steroid injection: analysis according to the neck pain patterns and MRI findings. Korean J Pain. 2016; 29:96–102. PMID: 27103964.

8. Ferrante FM, Wilson SP, Iacobo C, Orav EJ, Rocco AG, Lipson S. Clinical classification as a predictor of therapeutic outcome after cervical epidural steroid injection. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993; 18:730–736. PMID: 8516703.

9. Kwon JW, Lee JW, Kim SH, Choi JY, Yeom JS, Kim HJ, et al. Cervical interlaminar epidural steroid injection for neck pain and cervical radiculopathy: effect and prognostic factors. Skeletal Radiol. 2007; 36:431–436. PMID: 17340166.

10. Shakir A, Ma V, Mehta B. Prediction of therapeutic response to cervical epidural steroid injection according to distribution of radicular pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 90:917–922. PMID: 21955951.

11. Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Kent J, Mackey SC, Raja SN, Stacey BR, et al. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain. 2013; 154:2249–2261. PMID: 23748119.

12. Torrance N, Smith BH, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. J Pain. 2006; 7:281–289. PMID: 16618472.

13. Bouhassira D, Lantéri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain. 2008; 136:380–387. PMID: 17888574.

14. Carroll LJ, Cassidy JD, Côté P. Depression as a risk factor for onset of an episode of troublesome neck and low back pain. Pain. 2004; 107:134–139. PMID: 14715399.

15. Kim SH, Sun JM, Yoon KB, Moon JH, An JR, Yoon DM. Risk factors associated with clinical insomnia in chronic low back pain: a retrospective analysis in a university hospital in Korea. Korean J Pain. 2015; 28:137–143. PMID: 25852836.

16. Terry EL, DelVentura JL, Bartley EJ, Vincent AL, Rhudy JL. Emotional modulation of pain and spinal nociception in persons with major depressive disorder (MDD). Pain. 2013; 154:2759–2768. PMID: 23954763.

17. Fialová D, Onder G. Medication errors in elderly people: contributing factors and future perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009; 67:641–645. PMID: 19594531.

18. Avluk OC, Gurcay E, Gurcay AG, Karaahmet OZ, Tamkan U, Cakci A. Effects of chronic pain on function, depression, and sleep among patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. Ann Saudi Med. 2014; 34:211–216. PMID: 25266180.

19. Rabey M, Smith A, Beales D, Slater H, O'Sullivan P. Differing psychologically derived clusters in people with chronic low back pain are associated with different multidimensional profiles. Clin J Pain. 2016; 32:1015–1027. PMID: 26889613.

20. Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J, Newman S. Patient expectations: what do primary care patients want from the GP and how far does meeting expectations affect patient satisfaction? Fam Pract. 1995; 12:193–201. PMID: 7589944.

21. Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, Frankel RM. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice. Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994; 154:1365–1370. PMID: 8002688.

22. Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Entman SS, Miller CS, Githens PB, Whetten-Goldstein K, et al. Obstetricians' prior malpractice experience and patients' satisfaction with care. JAMA. 1994; 272:1583–1587. PMID: 7966867.

23. Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Githens PB, Sloan FA. Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992; 267:1359–1363. PMID: 1740858.

24. Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet. 1994; 343:1609–1613. PMID: 7911925.

25. Kim YD, Moon HS. Review of medical dispute cases in the pain management in Korea: a medical malpractice liability insurance database study. Korean J Pain. 2015; 28:254–264. PMID: 26495080.

26. Lester GW, Smith SG. Listening and talking to patients. A remedy for malpractice suits? West J Med. 1993; 158:268–272. PMID: 8460508.

27. Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995; 40:903–918. PMID: 7792630.

28. van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Esmail R, Koes B. Exercise therapy for low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000; 25:2784–2796. PMID: 11064524.

29. Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Herbert RD, Refshauge K. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006; 52:79–88. PMID: 16764545.

30. Friedrich M, Gittler G, Halberstadt Y, Cermak T, Heiller I. Combined exercise and motivation program: effect on the compliance and level of disability of patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998; 79:475–487. PMID: 9596385.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download