Abstract

Thalamic pain is a primary cause of central post-stroke pain (CPSP). Clinical symptoms vary depending on the location of the infarction and frequently accompany several pain symptoms. Therefore, correct diagnosis and proper examination are not easy. We report a case of CPSP due to a left acute thalamic infarction with central disc protrusion at C5-6. A 45-year-old-male patient experiencing a tingling sensation in his right arm was referred to our pain clinic under the diagnosis of cervical disc herniation. This patient also complained of right cramp-like abdominal pain. After further evaluations, he was diagnosed with an acute thalamic infarction. Therefore detailed history taking should be performed and examiners should always be aware of other symptoms that could suggest a more dangerous disease.

Thalamic pain is a type of central post-stroke pain (CPSP) that results in markedly variable clinical syndromes depending on the location of the infarction [123]. The clinical symptoms of CPSP can resemble other peripheral and central neuropathic pain symptoms [24]. Thus, it is not easy to diagnose CPSP immediately, because of the variable clinical features and the frequent concurrence of several pain symptoms [2]. The case below is a patient who was considered to have an ordinary cervical disc herniation but was found to have an acute thalamic infarction by detailed history taking and examination. We herein report a case of CPSP due to a left acute thalamic ischemic stroke with central disc protrusion at C5-6.

A 45-year-old-male patient was referred to our pain clinic due to a tingling sensation in his right arm. In the previous department of neurosurgery, medication consisting of Diclofenac and Eperisone had been administered for 3 weeks. The medications did not relieve symptoms. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the cervical spine was done at the previous department. C-spine CT showed a mild uncovertebral hypertrophy at C3-4 (right) and C5-6, posterior spurs at C5-6 and C6-7, and central disc protrusion at C5-6 (Fig. 1). A neurosurgery physician sent the patient to our pain clinic for a cervical epidural block. In the medical examination, he had no history of medical conditions, operations, or other diseases. Laboratory tests of blood revealed that all parameters were within the normal range. He complained of pain from the posterior neck to his right hand as a tingling sensation and numbness. Motor tone was Grade 5. Although a Spurling's test and a Jackson compression test were negative on physical examination, we first diagnosed cervical disc herniation. He was also suffering from right abdominal pain. It was present as a cramp-like abdominal pain confined to the right abdomen and no tenderness or rebound tenderness. We planned to perform an interlaminar cervical epidural steroid injection (C-ESI) under fluoroscopy for right arm pain and then to guide the patient to the medical department for abdominal pain. After informed consent about C-ESI was obtained, the patient was brought to the fluoroscopy room and placed in a prone position on the table. The posterior neck was draped and disinfected, and subcutaneous local anesthetics were injected. As we were about to do C-ESI, the patient complained of posterior upper thoracic abdominal cramp-like pain. We changed the patient's position from the prone to the supine. No associations were evident with abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness. Under the high suspicion of another disease, the procedure was cancelled and further evaluations were done. Reexamination and careful history taking cast doubt on our initial diagnosis. In particular, there was disagreement between imaging studies and clinical symptoms. C6 radiculopathy is usually associated with pain down the superior lateral aspect of the arm into the first two digits. However, the patient also complained of a tingling and cramp-like sensation in the ulnar forearm, and fourth and fifth fingers. The patient was also continually complaining of a cramping pain in the right abdomen of NRS 6, and this pain progressed with arm pain at the same time. With the possibility that a brain lesion could be the source of the pain, the patient was transferred to the department of neurology and further examination was performed. Diffusion weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to find the brain lesion. MRI revealed acute infarction in the left thalamus (Fig. 2). With the diagnosis of acute paramedian thalamic infarction, medication therapy was planned. Pregabalin, amitriptyline, choline alfoscerate, and aspirin were very effective in treating the patient's symptom without any invasive procedure. The pain intensity started to decrease 10 days after medication and ultimately decreased to a NRS rating of 2 out of 10. He is still being treated.

CPSP is defined as a direct result of a lesion associated with the central somatosensory system of the cerebral cortex, medulla, and thalamus [2]. It does not have well-recognized symptoms and markedly interferes with work, social relationships and mood [5]. The thalamus is important in the underlying mechanisms of CPSP [6]. The first descriptions of thalamic pain configured a syndrome characterized by a rapidly regressive mild hemiplegia, persistent superficial hemianesthesia (temperature, pain, and touch), mild hemiataxia, severe, paroxysmal, and intolerable pain on the hemiplegic side [7]. The human thalamus obtains blood supply from many perforating arteries, which exhibit many variations and complex distribution [8]. Thalamic infarction is usually considered a result of an occlusion of a supplying vessel [9]. In the paramedian thalamic region is the most commonly affected area, in which infarcts are usually asymmetrical [810]. Paramedian thalamic infarction is characterized by various neuropsychological deficits, somnolence, memory impairment, and supranuclear palsy [11]. Cramp-like pain, akinetic mutism, and dysathric disturbances may also be detected [7]. The clinical symptoms of CPSP are sometimes similar to those of other peripheral and central neuropathic pain syndromes. The time interval between stroke and CPSP onset varies, and CPSP can develop immediately after infarction in some patients and up to years later in others. Onset can be delayed, but development of pain within the first month is common [2]. There are no uniform signs of pathognomonic features with regard to intensity, presentation and onset, and the descriptions and characteristics of CPSP vary markedly between patients. The distribution of CPSP can range from a localized area to broad areas. The latter frequently involve the face and trunk. Hemibody pain is not uncommon in patients with thalamic infarction [2]. Diagnosis of CPSP is not easy, mainly because of different clinical features, frequent concurrence of several pain symptoms, and lack of definite diagnostic criteria for CPSP. The diagnosis must be confirmed on a combination of the history, imaging of lesions, sensory and clinical examination, and other clinical measures. Our case presented with a tingling sensation in the right arm and abdominal cramp-like pain. History-taking must include details of pain intensity, pain onset, and the presence of allodynia or dysesthesia; patients should be asked to indicate the area on a pain drawing [2]. The clinical examination should map the presence of sensory abnormalities and include quantitative sensory testing to confirm. The patient in our case had an accompanying thalamic pain and cervical disc herniation. However, in a careful history-taking and physical examination, the patient mainly complained of right abdominal cramp-like pain, rather than tingling sensation in the right arm and hand, caused by a cervical herniated intervertebral disc. In addition, the patient had shown no improvement from the medication for a cervical herniated intervertebral disc before visiting our pain clinic. Therefore, thalamic pain after acute thalamic infarction was regarded as the main problem and treatment was carried out. In the present case, even though the patient had a disc herniation in the cervical region, we assumed that this cervical disc herniation was asymptomatic. Both cervical radiculopathy and abdominal cramp-like pain began simultaneously, and symptoms did not accord with the C6 dermatome. Thalamic pain is a type of CPSP. It is often excruciatingly painful and not treatable with conventional analgesics [3]. Treatment of CPSP in clinical practice is often based on trial and error until pain relief is found [2]. Anticonvulsant drugs like gabapentin and pregabalin can reduce neuronal hyperexcitability. The efficacy of those drugs on central and peripheral neuropathic pain is well documented [12]. Antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and amitriptyline, have been used to treat this symptom [3]. Opioids sometimes effectively relieve CPSP, but are not considered as a first-line treatment. Besides, when oral treatment was not well tolerated owing to side-effects, treatment with intravenous lidocaine, propofol, and morphine alleviated pain during infusion [213]. In treatment-resistant cases of CPSP, neurostimulation therapy, such as deep brain stimulation, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and motor cortex stimulation is used [2]. The patient in our case started medical treatment with pregabalin, amitriptyline, and choline alfoscerate. After treatment, the symptom was much improved.

Several types of pain can occur in the same patient. Thus, it is important to identify the type and origin of pain to find the appropriate treatment. Diagnosis of thalamic pain must be based on pain, medical and past history, imaging of the lesion, and clinical examination. This case raises the awareness of rare causes of cramp-like thalamic pain related to thalamic infarction. Stereotypical thinking can lead to misdiagnosis and missing something important. Pain physicians should include thalamic infarction in the differential diagnosis of any cramp-like pain associated with cervical radiculopathy, despite its rarity.

References

1. Giannopoulos S, Kostadima V, Selvi A, Nicolopoulos P, Kyritsis AP. Bilateral paramedian thalamic infarcts. Arch Neurol. 2006; 63:1652. PMID: 17101838.

2. Klit H, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. Central post-stroke pain: clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2009; 8:857–868. PMID: 19679277.

3. Ueda K, Namiki T, Kasahara Y, Chino A, Okamoto H, Ogawa K, et al. A case of thalamic pain successfully treated with Kampo medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2011; 17:567–570. PMID: 21574822.

4. Vestergaard K, Nielsen J, Andersen G, Ingeman-Nielsen M, Arendt-Nielsen L, Jensen TS. Sensory abnormalities in consecutive, unselected patients with central post-stroke pain. Pain. 1995; 61:177–186. PMID: 7659427.

5. Bugnicourt JM, Garcia PY, Canaple S, Lamy C, Godefroy O. Central neuropathic pain after cerebral venous thrombosis is not so uncommon: an observational study. J Neurol. 2011; 258:1150–1156. PMID: 21287188.

7. Sposato LA, Sharma HA, Khan AR, Bartha R, Hachinski V. Thalamic cramplike pain. J Neurol Sci. 2014; 336:269–272. PMID: 24210074.

8. Koutsouraki E, Xiromerisiou G, Costa V, Baloyannis S. Acute bilateral thalamic infarction as a cause of acute dementia and hypophonia after occlusion of the artery of Percheron. J Neurol Sci. 2009; 283:175–177. PMID: 19442987.

9. Gossner J, Larsen J, Knauth M. Bilateral thalamic infarction--a rare manifestation of dural venous sinus thrombosis. Clin Imaging. 2010; 34:134–137. PMID: 20189078.

10. Krolak-Salmon P, Croisile B, Houzard C, Setiey A, Girard-Madoux P, Vighetto A. Total recovery after bilateral paramedian thalamic infarct. Eur Neurol. 2000; 44:216–218. PMID: 11096220.

11. Lok U, Yalin O, Odes R, Bozkurt S, Gulacti U. Bilateral thalamic infarct as a diagnosed conversion disorder. Am J Emerg Med. 2013; 31:889.e1–889.e3. PMID: 23399329.

12. Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, Jensen TS, Sindrup SH. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence based proposal. Pain. 2005; 118:289–305. PMID: 16213659.

13. Canavero S, Bonicalzi V. Intravenous subhypnotic propofol in central pain: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004; 27:182–186. PMID: 15319705.

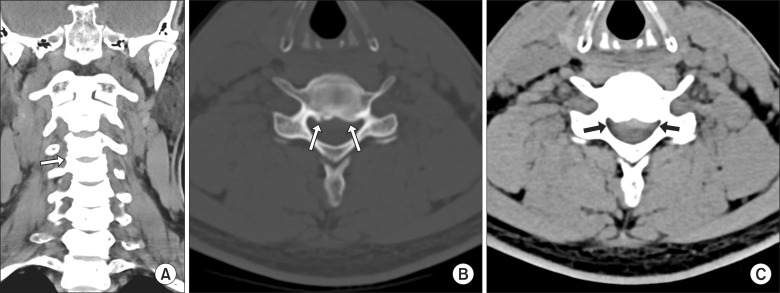

Fig. 1

Coronal plane of cervical spine computed tomography (CT) showing a mild uncovertebral hypertrophy at right side of C3-4 (A). Posterior spurs at C5-6 is shown on bone window setting of axial plane of cervical spine (B) and central protrusion at C5-6 is shown on soft tissue window setting of same image as well (C).

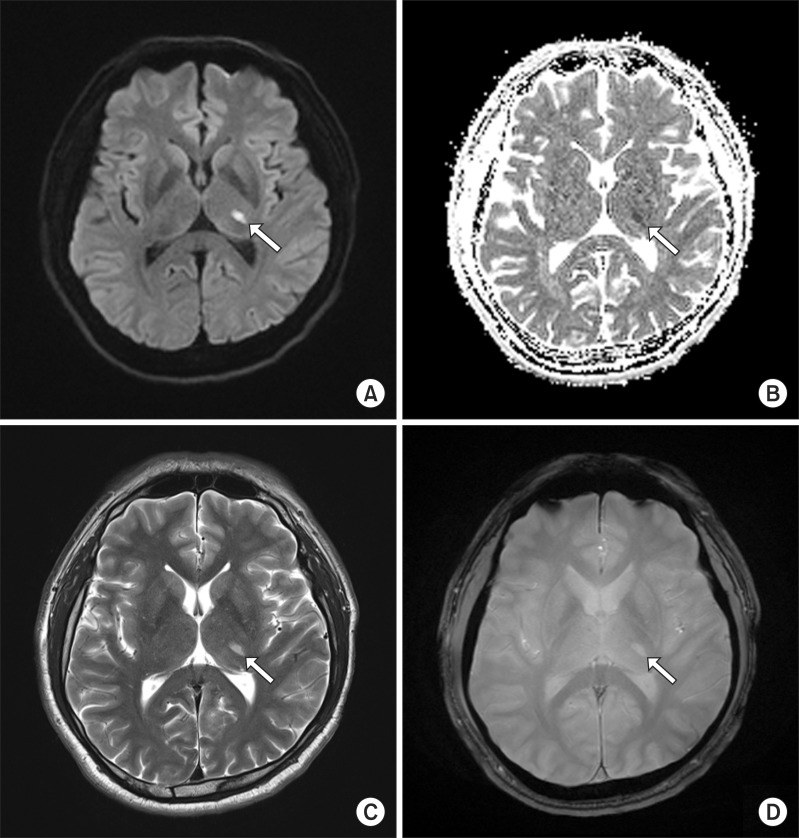

Fig. 2

Magnetic resonance (MR) diffusion image shows acute infarction at left thalamus. The lesion is on the posterolateral area of left thalamus. (A) is b1000 DWI. (B) is ADC map which shows the lesion along the arrow. The lesion is shown on T2WI (C) and T2FLAIR (D) as high signal. TOF-MR angiography shows no remarkable finding in intracranial major vessels.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download