Abstract

Background

The word "geop" is a unique Korean term commonly used to describe fright, fear and anxiety, and similar concepts. The purpose of this pilot study is to examine the correlation between the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) score of geop and three different questionnaires on pain perception.

Methods

Patients aged 20 to 70 years who visited our outpatient pain clinics were evaluated. They were requested to rate the NRS score (range: 0-100) if they felt geop. Next, they completed questionnaires on pain perception, in this case the Korean version of the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire (PSQ), the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), and the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS). The correlations among each variable were evaluated by statistical analyses.

Results

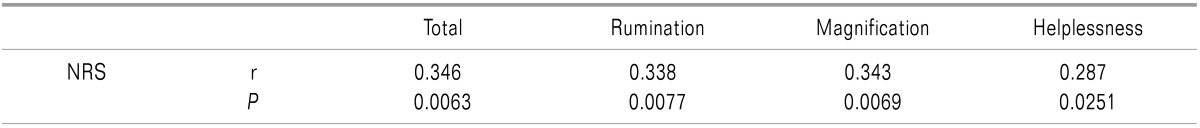

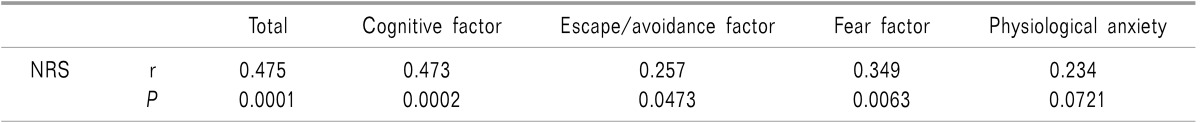

There was no statistically significant correlation between the NRS score of geop and the PSQ score (r = 0.075, P = 0.5605). The NRS score of geop showed a significant correlation with the PCS total score (r = 0.346, P = 0.0063). Among the sub-scales, Rumination (r = 0.338, P = 0.0077) and Magnification (r = 0.343, P = 0.0069) were correlated with the NRS score of geop. In addition, the NRS score of geop showed a significant correlation with the PASS total score (r = 0.475, P = 0.0001). The cognitive (r = 0.473, P = 0.0002) and fear factors (r = 0.349, P = 0.0063) also showed significant correlations with the NRS score of geop.

Pain can be defined as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage" [1]. Pain is always subjective and personal; the interpretation of or response to pain can be varied in accordance with the individual perception of the pain. It is widely known that an increase in pain perception or sensitivity is a significant risk factor in the transition to chronic pain [2]. Due to the significant role of "perception" in pain, one can also suffer groundless subjective physical and psychological pain distinct from actual physical conditions, as a result of inappropriate or irrational cognitive processes which distort and exaggerate the intensity of pain or inconvenience [3].

There are several measurement tools with which to assess individual pain perception, including the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire (PSQ) [4], the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [5], and the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS) [6]. However, these questionnaires are lengthy, cumbersome, and confounding to patients who often complain of having difficulty in understanding the questions. The word "geop" is a Korean word reflecting the unique Korean culture; the dictionary describes this word as "afraid or frightened mind" [7]. This word can be likened to certain English words that express fear of some sort, such as fright, anxiety, terror, and fear. Notwithstanding, fear is an immediate alarm reaction to a present threat that can result in a surge of sympathetic arousal, while anxiety is a negative emotion affect and apprehensive anticipation of potential threats that can induce hypervigilance and somatic tension [8]. Moreover, unlike "geop," fear and anxiety are responses to certain objects, although they differ in terms of time. That being said, "geop" is a unique and distinctive concept that embodies a variety of different meanings. Practically no research has addressed the concept of "geop." Nor are there indicators that can assess "geop" with regard to pain. Hence, pondering the question of whether people with a considerable amount of "geop" feel more pain, the author of this study aimed to examine the correlation between the level of "geop" using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and pain perception.

As noted above, the purpose of this pilot study is to examine the correlation between the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) score of geop and three different questionnaires on pain perception and subsequently to identify any correlations between the questionnaires and specific items of a questionnaire.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the author's university. The study was conducted on adult patients of 20-70 years of age who visited a pain clinic, and no particular disease was targeted. The subjects had to be capable of voluntarily communicating and expressing their thoughts in Korean as well as responding to the questionnaire without any help from others. Those who could not voluntarily communicate, answer the questionnaire without help, or who visited the clinic for cancer pain were excluded from the study. Those who declined to participate were also excluded from the study. Because there is no existing research on "geop," we could not calculate the number of subjects based on previous correlations. Thus, this study did not calculate the number of subjects and instead was conducted as a pilot study on "geop" as well as an exploratory survey of the correlations and trends between "geop" and existing pain questionnaires with outpatients visiting a pain clinic during a specified period (June 2, 2014-June 14, 2014; 2 weeks).

After we explained the purpose and objective of this study to the subjects, we asked them to answer the following question: "Please indicate your level of "geop" on a 101-point scale, 0 being no geop at all and 100 representing the highest imaginable level of geop possible." Subsequently, we administered three questionnaires: the Korean version of the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire (PSQ) [4], the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) [5], and the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS) [6]. All of these have had their validity and reliability levels formerly verified [9,10,11].

The PSQ assumes various daily pain situations and is based on a self-rating of pain intensity on different body parts [4]. It is composed of 17 items, and each item is rated on an 11-point scale, from 0 (does not seem painful at all) to 10 (seems like the most excruciating pain imaginable). We used the mean value of all 17 items as preliminary data. The PCS is a 13-item questionnaire developed to measure various levels of pain catastrophizing [5]. Each item is rated on a five-point scale, from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time); the scale is divided into three sub-scales to be analyzed (Rumination, four items; Magnification, three items, and Helplessness, six items). We used the total score of all 13 items and the sum of the scores of each sub-item as preliminary data. The PASS is a scale which is used to measure pain-related anxiety. It consists of 20 items measured on a six-point scale from 0 (never) to 5 (always). There are four sub-scales with five items each (Cognitive factor, Escape/Avoidance factor, Fear factor, Physiological anxiety). As with PCS, we used the total score and the sum of each sub-scale as preliminary data.

We examined the correlation between the scores of each questionnaire with that of NRS assessing geop. For PCS and PASS, we also analyzed the correlation with each sub-scale. Furthermore, we examined the correlations among the three questionnaires.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (Version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). The demographic data and scores for the questionnaires were expressed in the form of the mean ± standard deviation. Cronbach's α was used to evaluate internal consistency; the correlations among preliminary data were measured using Pearson's correlation. In this study, Pearson's correlation was defined as follows: r < 0.3, weak; 0.3 < r < 0.7, moderate; r > 0.7, strong [12]. P values of less than 0.05 were deemed to be statistically significant.

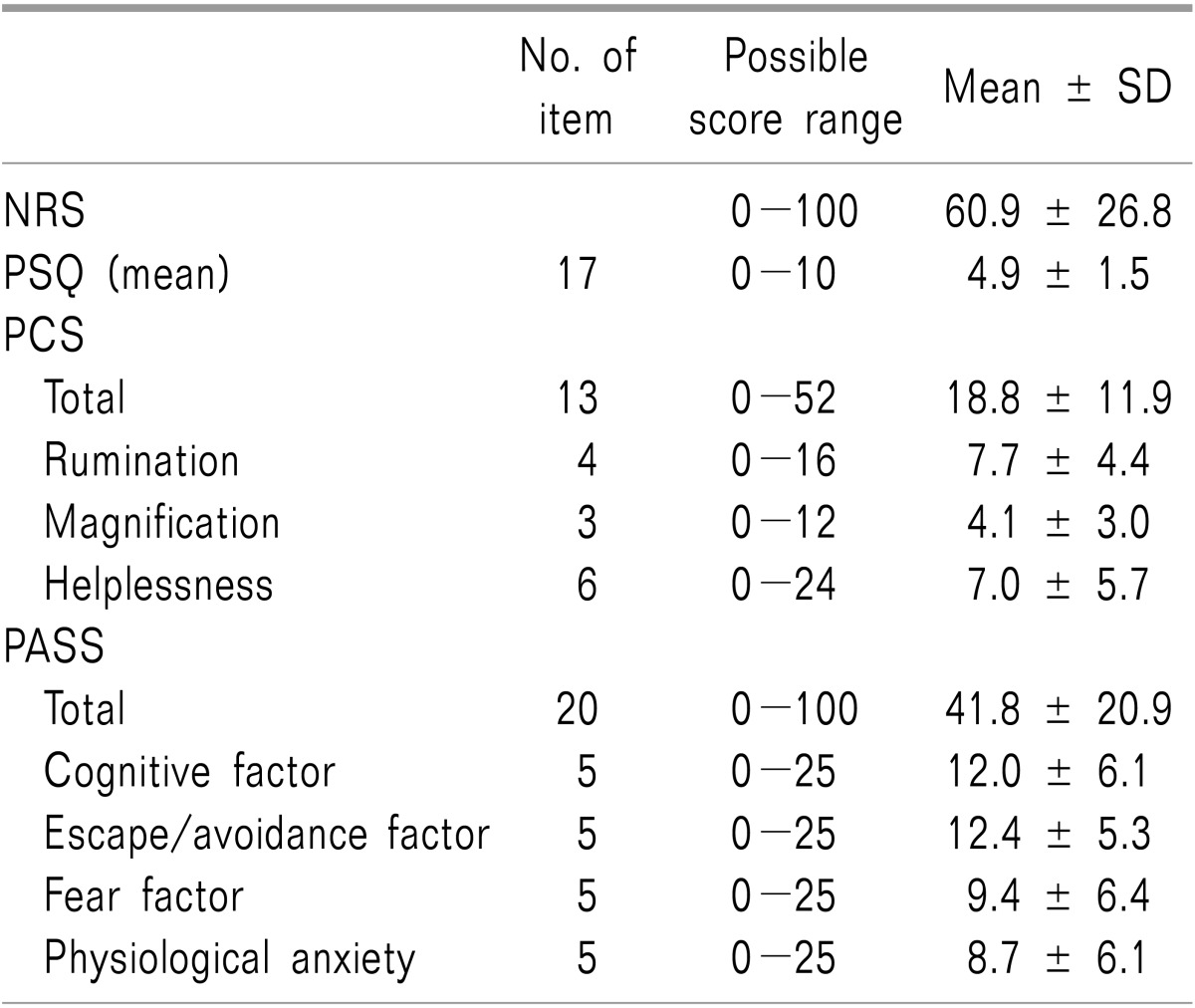

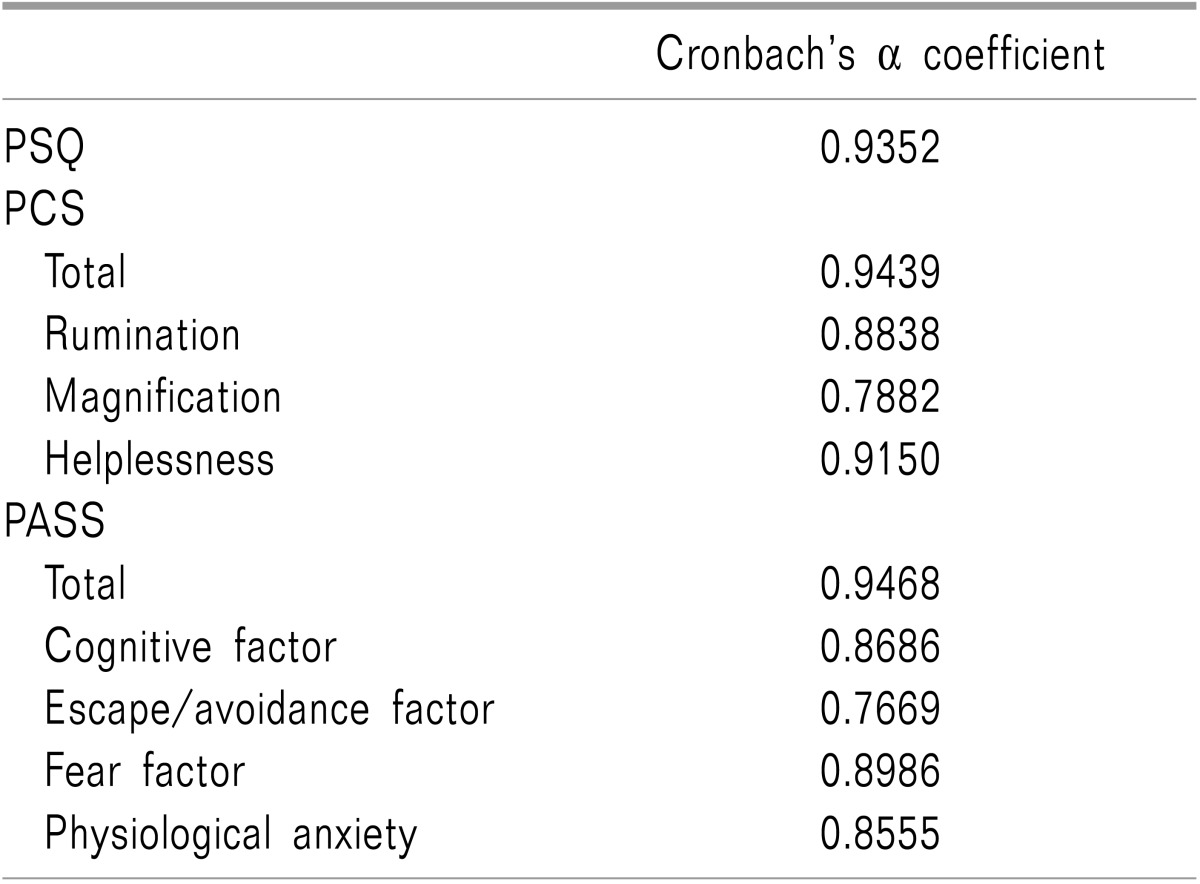

Out of 64 subjects, 23 were male and 41 were female, with an average age of 41.3 ± 14.5 years. Fifty eight subjects answered all of the items; only the answered items were analyzed for those questionnaires with omitted answers. The mean NRS score for the geop assessment (of which 63 patients answered) was 60.9, while those for PSQ, PCS, and PASS were 4.9 ± 1.5, 18.8 ± 11.9, and 41.8 ± 20.9, respectively (Table 1). The Cronbach's α values which verify the internal consistency were 0.9352, 0.9439 and 0.9468 for PSQ, PCS and PASS, respectively (Table 2). There was no statistically significant correlation between the NRS score for geop and the PSQ score (r = 0.075, P = 0.5605). However, there was a statistically significant moderate correlation between the NRS score for geop and the PCS score (r = 0.346, P = 0.0063). The NRS score for geop was also significantly moderately correlated with two sub-scales of PCS-Rumination (r = 0.338, P = 0.0077), and Magnification (r = 0.343, P = 0.0069)-and weakly correlated with Helplessness (r = 0.287, P = 0.0251) (Table 3). The NRS score for geop had a significant moderate correlation with the total score of PASS (r = 0.475, P = 0.0001); they were moderately correlated with the two sub-scales of PASS-the Cognitive factor (r = 0.473, P = 0.0002) and the Fear factor (r = 0.349, P = 0.0063)-and were weakly correlated with the Escape/Avoidance factor (r = 0.257, P = 0.0473) (Table 4).

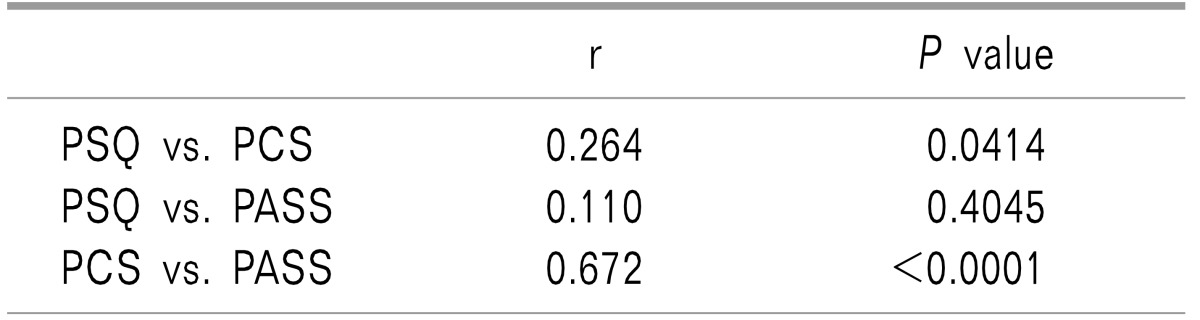

An analysis of the correlations among the three questionnaires revealed that PSQ and PCS had a statistically significant weak correlation, while PCS and PASS showed a significant moderate correlation (Table 5).

The mean score of NRS for geop was 60.9, and it did not show a statistically significant correlation with the PSQ scores. However, it had a statistically significant moderate correlation with the PCS and PASS scores.

Analyzing the internal consistencies showed that the Cronbach's α values for PSQ and PCS total and the sub-scale, as well as the PASS total and sub-scale scores, were all above 0.7. A Cronbach's α value of greater than 0.7 signifies that the research design and methods are appropriate with good adequate internal consistency [13].

The PSQ is a useful tool developed by Ruscheweyh et al. [4] for measuring an individual's pain sensitivity. According to Ruscheweyh et al. [14], the PSQ scores of healthy individuals and that of patients with chronic pain are 3.4 and 4.0, respectively. Furthermore, they reported that the PSQ score was significantly correlated with experimental pain thresholds and pain intensity rating scores as measured using heat, cold, pressure and pinpricks [14]. Kim et al. [9] conducted a Korean-translated questionnaire survey with 72 patients with chronic pain and reported that the mean PSQ score of the patients was 5.93, which was a statistically significant correlation with the PCS score. The PSQ score of the subjects in the present study was 4.9, and there was no statistically significant correlation with the NRS score for geop. This illustrates that the PSQ emphasizes the sensory aspect of pain that explains pain sensitivity, while the NRS score for geop does not significantly reflect the equivalent sensory aspect of pain that explains pain sensitivity.

Sullivan et al. [5] developed the PCS in 1995. It evaluates the thinking and emotion that arise during pain. "Catastrophizing" is defined as an exaggerated negative "mental set" brought to bear during the actual or anticipated experience of pain [15]; it is an important psychological construct which mediates the behavioral response toward pain [5]. PCS is currently one of the most commonly used tools for evaluating pain-related catastrophizing. Lim et al. [16] reported that the total PCS score of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain was 18.2 and that of each of the sub-scales Rumination, Magnification, and Helplessness were 6.6, 4.0, and 7.6, respectively. They also reported that there was a significant-although weak-correlation among the intensity, frequency, somatization and catastrophizing of pain [16]. Hence, it can be said that when the intensity and frequency of pain increase in patients with chronic pain, the patients become physically more sensitive and they direct their attention to pain-related fear and other catastrophic thoughts. Preceding studies showed that Rumination was significantly related to increases in pain intensity, frequency and anxiety; furthermore, Magnification was also shown to be linked to increases in depression and anxiety [16]. Cho et al. [10] reported that the PCS total, Rumination, Magnification, and Helplessness scores of patients with chronic non-cancer pain were 27.68, 11.50, 5.77, and 10.63, respectively. They also found a significant moderate correlation with pain intensity as measured with the NRS.

A comparison of the PCS total and sub-scale scores with the NRS score for geop revealed that the NRS score for geop was moderately correlated with the PCS total, Rumination and Magnification scores. This finding indicates that individuals with considerable amounts of geop tend to think about pain repeatedly and exaggeratedly, which ultimately incites an increase of catastrophic thinking.

Pain-related anxiety and avoidance behavior can have a severe influence on physical and mental adaptations in patients with chronic pain [17,18]. The most commonly employed method in research and clinics to measure pain-related anxiety is the PASS [6,19]. The PASS-20 (heretofore referred to as PASS) is an abridged version of the initial 40-item PASS. Its structure has been confirmed to be the most stable for clinical use, and the scale's validity and reliability have been verified as well [20]. As noted, PASS is a self-report instrument that consists of 20 items in the four distinct categories of cognitive factors, escape/avoidance factors, fear factors, and physiological anxiety. Although it is commonly utilized in the West, it has not been fully accepted in the Asian sociocultural space. This is due to differences in pain expressions and responses among different cultures [21] Asians have a unique social perception that values enduring and repressing pain and pain-related emotions (e.g., anxiety and depression), which compels them to minimize external expressions of pain in comparison to Europeans or Americans [22]. The PASS score for the subjects of this study was 41.83, showing a significant moderate correlation with the NRS score for geop. More specifically, the cognitive factor and fear factor showed a significant moderate correlation with the NRS score for geop. The cognitive factor assesses pain-induced cognitive anxiety symptoms, such as concentration impairment and racing thoughts, while the fear factor assesses pain-induced fearful thoughts and anticipated negative consequences [23]. Once again, geop is a Korean word indicating an "afraid or frightened mind" [7], and the cognitive and fear factors show more significant correlations with geop as compared to the other two factors (i.e., escape/avoidance factor and physiological anxiety). McCracken and Dhingra [6] reported findings similar to our study, as the PASS score assessed from chronic pain patients was 38.62 while the cognitive factor, escape/avoidance factor, fear factor, and physiological anxiety scores were 12.27, 12.84, 7.37, and 6.15, respectively. Abrams et al. [20] assessed non-patients' PASS scores and reported an average of 24.04, which shows quite a gap compared to that of the patients assessed by McCracken and Dhingra [6] This is a lucid demonstration of the fact that pain-induced anxiety, avoidance and fear are highly contributory to increased PASS scores.

As has been noted, the PSQ score, which reflects individual differences in pain sensitivity levels (the sensory aspect of pain), was not significantly correlated with the NRS score, which assesses geop. On the other hand, the emotional aspect of pain, in this case catastrophizing and anxiety, were significantly correlated with the NRS score for geop. In essence, the answer to the question, "Do people with more geop feel more pain?" is that people with more geop tend to engage in considerable amounts of pain-related worrying and have much anxiety. Nevertheless, we cannot conclude whether people with high amounts of geop will feel more pain. The way NRS used to assess geop in its current form is insufficient when used to represent all aspects of the previously mentioned questionnaires; therefore, additional factors that reflect individual differences in sensitivity should be incorporated.

Lastly, analyzing the correlations among the three questionnaires showed that the PCS and PASS scores had a statistically significant moderate correlation. Considering that the items on these two questionnaires relatively emphasize the emotional aspects of pain perception, we can liken their correlation to that between the NRS score for geop and PCS, and that between the NRS score for geop and the PASS score.

Whereas numerous studies have evaluated questionnaires that assess pain and pain sensitivity and perception [4,5,6], not even a single study has explored the concept of "geop." Hence, this study is valuable because it is the first explorative survey which uses the concept of "geop." However, despite this value, this study is limited in several ways. First, we did not consider the fundamental factors of pain in the subjects. Since the initial purpose of this study was simply to compare the scores on pain perception questionnaires to NRS scores for geop while discounting all other factors, we did not ask our subjects about any other information other than gender and age. However, we do realize that basic pain-related information, such as pain intensity and duration, pain treatment progress, and pain sites can severely affect the scores of the NRS for geop and other questionnaires, which prevented this study from factoring in individual differences that can arise from such effects. Second, we lacked information and knowledge on behavioral factors that can affect individual pain perception. It is suggested that not only psychological factors but also behavioral factors (e.g., the degree of social activity engagement, interpersonal relationship and work-related activities) that can affect pain assessments should be examined. Finally, we cannot completely eliminate biases with regard to the number of subjects, structural limitations, age, and gender; furthermore, we cannot predict any findings regarding non-patient groups because we only surveyed outpatients with pain.

Given these points, this study was the first exploratory study to use the concept of "geop" and compare NRS scores as a means of assessing geop to other existing pain perception questionnaires. Our findings indicate that the NRS score for geop has a statistically significant correlation with that of PCS and PASS. However, as this study was only a pilot study, additional research and measurement tools with which to assess the sensory aspect of pain are required to establish the NRS for geop as an accurate scale reflecting pain perception. We hope our study will be conducive to the ultimate development of a tool that can anticipate patients' tendencies with regard to pain by providing a scale for geop to assess pain.

References

1. Merskey H, Lindblom U, Mumford JM, Nathan PW, Sunderland SS. Part III. Pain terms: a current list with definitions and notes on usage. In : Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2nd ed. Seattle (WA): IASP Press;1994. p. 209–214.

2. Edwards RR. Individual differences in endogenous pain modulation as a risk factor for chronic pain. Neurology. 2005; 65:437–443. PMID: 16087910.

3. Roth RS, Geisser ME, Theisen-Goodvich M, Dixon PJ. Cognitive complaints are associated with depression, fatigue, female sex, and pain catastrophizing in patients with chronic pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005; 86:1147–1154. PMID: 15954053.

4. Ruscheweyh R, Marziniak M, Stumpenhorst F, Reinholz J, Knecht S. Pain sensitivity can be assessed by self-rating: development and validation of the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire. Pain. 2009; 146:65–74. PMID: 19665301.

5. Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995; 7:524–532.

6. McCracken LM, Dhingra L. A short version of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20): preliminary development and validity. Pain Res Manag. 2002; 7:45–50. PMID: 16231066.

7. Lee KM. Donga new Korean dictionary. 5th ed. Seoul: Doosan Donga;2013.

8. Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. Fear and anxiety: divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain. 2000; 84:65–75. PMID: 10601674.

9. Kim HJ, Ruscheweyh R, Yeo JH, Cho HG, Yi JM, Chang BS, et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validity of the Korean version of the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire in chronic pain patients. Pain Pract. 2014; 14:745–751. PMID: 24131768.

10. Cho S, Kim HY, Lee JH. Validation of the Korean version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Qual Life Res. 2013; 22:1767–1772. PMID: 23180163.

11. Cho S, Lee SM, McCracken LM, Moon DE, Heiby EM. Psychometric properties of a Korean version of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-20 in chronic pain patients. Int J Behav Med. 2010; 17:108–117. PMID: 20186509.

12. Kirkwood BR, Sterne JA. Chapter 10. Linear regression and correlation. In: Essential medical statistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd;2003. p. 93–96.

13. Veenhof C, Bijlsma JW, van den Ende CH, van Dijk GM, Pisters MF, Dekker J. Psychometric evaluation of osteoarthritis questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 55:480–492. PMID: 16739188.

14. Ruscheweyh R, Verneuer B, Dany K, Marziniak M, Wolowski A, Colak-Ekici R, et al. Validation of the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire in chronic pain patients. Pain. 2012; 153:1210–1218. PMID: 22541722.

15. Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001; 17:52–64. PMID: 11289089.

16. Lim KB, Kim JY, Lee HJ, Kim DY, Kim JM. The relations among pain, emotional and cognitive-behavioral factors in chronic musculoskeletal pain patients. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2008; 32:424–429.

17. Burns JW, Mullen JT, Higdon LJ, Wei JM, Lansky D. Validity of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS): prediction of physical capacity variables. Pain. 2000; 84:247–252. PMID: 10666529.

18. Philips HC. Avoidance behaviour and its role in sustaining chronic pain. Behav Res Ther. 1987; 25:273–279. PMID: 3662989.

19. McCracken LM, Zayfert C, Gross RT. The Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale: development and validation of a scale to measure fear of pain. Pain. 1992; 50:67–73. PMID: 1513605.

20. Abrams MP, Carleton RN, Asmundson GJ. An exploration of the psychometric properties of the PASS-20 with a nonclinical sample. J Pain. 2007; 8:879–886. PMID: 17690016.

21. Morse JM, Morse RM. Cultural variation in the inference of pain. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1988; 19:232–242.

22. Hobara M. Beliefs about appropriate pain behavior: cross-cultural and sex differences between Japanese and Euro-Americans. Eur J Pain. 2005; 9:389–393. PMID: 15979019.

23. Coons MJ, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Asmundson GJ. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-20 in a community physiotherapy clinic sample. Eur J Pain. 2004; 8:511–516. PMID: 15531218.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download