Abstract

Psychosomatic disorders are defined as disorders characterized by physiological changes that originate partially from emotional factors. This article aims to discuss the psychosomatic disorders of the oral cavity with a revised working type classification. The author has added one more subset to the existing classification, i.e., disorders caused by altered perception of dentofacial form and function, which include body dysmorphic disorder. The author has also inserted delusional halitosis under the miscellaneous disorders classification of psychosomatic disorders and revised the already existing classification proposed for the psychosomatic disorders pertaining to dental practice. After the inclusion of the subset (disorders caused by altered perception of dentofacial form and function), the terminology "psychosomatic disorders of the oral cavity" is modified to "psychosomatic disorders pertaining to dental practice".

Go to :

Psychosomatic disorders are defined as disorders characterized by physiological changes that originate partially from emotional factors. Psychosomatic disorders can affect the oral cavity since the oral environment is related directly or symbolically to the major human instincts and passions and is charged with a high psychological potential [1]. Psychosomatic disorders may be due to several biochemical disorders involving neurotransmitters in the brain, incomplete connections with in the oral region and undefined complaints due to cognitive processes in higher centers of the brain [2].

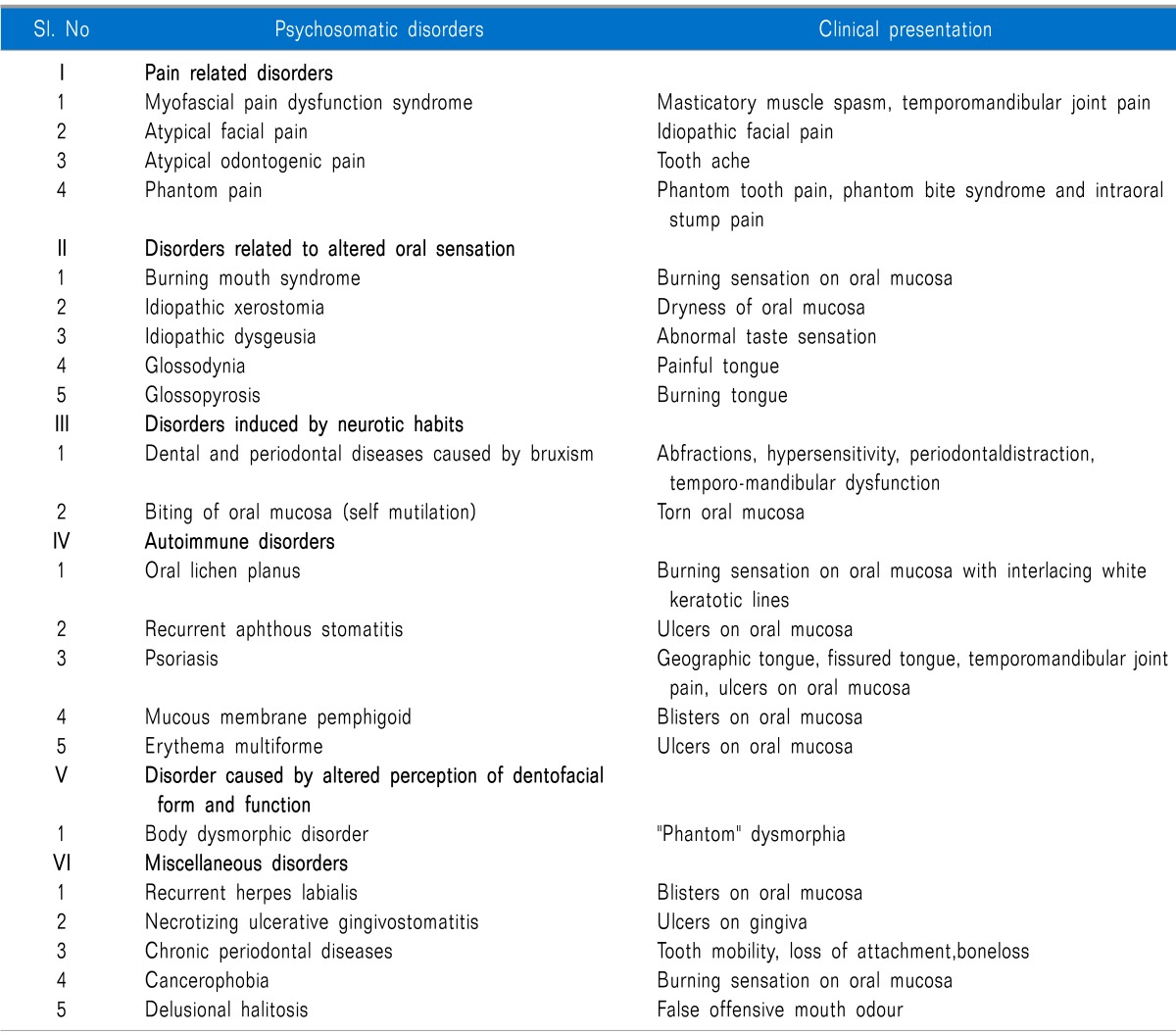

A simple working type classification has already been proposed for the psychosomatic disorders of the oral cavity [3]. This article aims to discuss the psychosomatic disorders pertaining to dental practice with a revised working type classification. The simple working type classification includes pain related disorders, disorders related to altered oral sensation, disorders induced by neurotic habits, autoimmune disorders, and miscellaneous disorders.

Go to :

Pain related disorders include disorders of the orofacial region presenting with vague pain attributed to psychological stress [3]. This category includes myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome (MPDS), atypical facial pain, atypical odontogenic pain, and phantom pain.

Myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome (MPDS) of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a psychophysiological disorder that develops as a result of hyperactive muscles of mastication. In this syndrome, the changes in chronic masticatory muscle pain seem to be attributed to psychological stress [4]. In a preliminary study performed on patients with temporomandibular joint disorders, using Research Diagnostic Criteria (Axis II), it was found that more severe depressive and nonspecific physical symptoms were evident in patients with MPDS [5].

Atypical facial pain is persistent idiopathic facial pain which lacks clear diagnostic criteria and standard treatment. Occlusal factors are less important and psychological and biochemical factors are recognized in its etiology [6]. Atypical facial pain may be related to apical fenestration and overfilling [7].

Atypical odontogenic pain is a chronic form of dental pain without signs of pathology. The pathophysiology has been proposed to be psychogenic, vascular, neuropathic, or idiopathic [8]. Dental surgeons are most likely to encounter these patients, and reaching a definitive diagnosis of atypical odontogenic pain can be a complex challenge [9].

Phantom pain involves the sensation of pain in a part of the body that has been removed (most often associated with limb amputation). In the oral cavity, phantom tooth pain is usually associated with tooth extraction [10]. The theory and phenomenology of orofacial phantom pain in the oral cavity can be graded into phantom tooth pain, phantom bite syndrome, and intraoral stump pain [11]. Marbach described the term "phantom bite" as a patient's perception of an irregular bite when the clinician could identify no evidence of a discrepancy [12].

Go to :

Disorders related to altered oral sensation are disorders in which the clinical presentation of the patient may be a persistent intraoral burning sensation [3]. This category includes burning mouth syndrome, idiopathic xerostomia, idiopathic dysgeusia, glossodynia, and glossopyrosis.

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is a disorder presenting with an intraoral burning sensation for which no medical or dental cause can be found. Poor quality of life, depression, anxiety, and somatization are also often associated with this disorder. The available literature suggests that burning mouth syndrome is a multifactorial disorder associated with psychological components such as anxiety, depression, and cancerophobia [13]. The psychological aspects of burning mouth syndrome can be categorized into chronic somatoform dysfunction, chronic vegetative disorders, and chronic pain phenomenon [14].

Xerostomia is a common condition associated with quantitative and qualitative changes in saliva, which are generally referred to as salivary hypofunction (dry mouth). This can be caused by various systemic diseases such as Sjogren's syndrome, the anticholinergic effects of many medications, psychological conditions, and physiological changes [15]. Depressive symptoms are usually evident in individuals with idiopathic subjective dry mouth [16].

Dysgeusia refers to persistent abnormal taste. It can also occur as a result of dry mouth, as adequate saliva is necessary for the function of taste, or it can be secondary to burning mouth syndrome in psychiatric patients [13]. Dysgeusia is a common oral side effect of cancer therapy (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or combined modality therapy) and often impacts negatively on quality of life [17]. Unfortunately, the underlying causes are often not found, and the majority of patients are considered idiopathic dysgeusia cases [18].

Glossopyrosis is a burning sensation of the tongue. It is usually associated with burning mouth syndrome. This condition may be the result of gastrointestinal, immunologic, neurologic, psychiatric, and dermatologic diseases. Lengthy periods of depression tend to be seen before the manifestation of the full clinical picture of glossopyrosis [21]. Lingual burning in patients with glossopyrosis is consistent with hyperalgesia, and neurogenic inflammation is observed in patients and animals with magnesium deficiency and in magnesium-deficient tissues [22].

Go to :

Disorders induced by neurotic habits are disorders induced by parafunctional activity of the soft and hard tissues of the oral cavity [3]. This category includes dental and periodontal diseases caused by bruxism and biting of the oral mucosa (self-mutilation).

Bruxism is the parafunctional clenching and grinding action between the upper and lower teeth. During this activity, extremely strong forces can be applied for periods of time exceeding those of functional mastication. These biomechanical loads create many dental problems, such as abfractions, hypersensitivity, periodontal distraction, and temporomandibular dysfunction [23]. The physiology and pathology of bruxism are unknown, although stress and anxiety are considered to be risk factors [24]. Behavioral problems and potential emotional problems have been found to be potential risk factors for bruxism in children [25].

Self-mutilation due to biting of the oral mucosa originates as a result of chronic cheek, lip, or tongue biting [26]. These lesions are often observed in people who are under stress, and psychogenic background must be ruled out in individuals who exhibit this activity. This type of behavior may also be exhibited in cases in which people wish to obtain special attention from family members.

Go to :

Autoimmune disorders are common dermatologic diseases with oral manifestations with psychological stress as an etiologic factor in the disease progression [3]. This category includes recurrent aphthous stomatitis, lichen planus, psoriasis, mucous membrane pemphigoid, and erythema multiforme.

Lichen planus is a common chronic immunologic inflammatory disease of the mucosa and skin presenting as interlacing white keratotic lines (Wickham's striae) typically located bilaterally on the buccal mucosa [27]. The exact etiology of OLP is unknown, but it is thought to arise due to immunologic disturbances (T-cell mediated and antigen-specific mechanisms). It is currently considered to be a disease that develops as a psychiatric problem due to depression, anxiety, and stress [28].

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is the most common type of ulcerative disease of the oral mucosa. RAS can be a manifestation of a serious health condition, such as an autoimmune disorder, human immunodeficiency virus, infection, and hematologic or oncologic disorders [29]. Psychological stress may play a role in the manifestation of RAS and it may serve as a trigger or a modifying factor rather than being a cause of the disease [30].

Psoriasis is a common dermatologic disorder that displays an association with stress or psychological distress [31]. There is a significant association between pustular psoriasis and an oral lesion, such as geographic tongue and fissured tongue [32]. Psoriasis may also manifest as inflammatory temporomandibular joint lesions and gingival and mucosal lesions.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid, a heterogeneous group of autoimmune blistering diseases, affects primarily the mucous membranes (oral and ocular mucosa) [33]. Diseases in this group have been noted to be associated with stress and depression as predisposing factors.

Oral erythema multiforme (EM) can present with oral and lip ulcerations without manifesting target lesions on the skin [34]. This disease may occur secondary to herpetic infection. In herpes-associated EM, it is most likely that HSV-DNA fragments in the skin or mucosa precipitate the disease [35]. In this case, the role of stress is evident with deregulation of T-lymphocyte activity.

Go to :

Miscellaneous disorders comprise an unclassified category in which the role of stress is important in the disease progression [3]. This category includes recurrent herpes labialis, necrotizing ulcerative gingivostomatitis, chronic periodontal diseases, and cancerophobia.

Recurrent herpes labialis is a mucocutaneous infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) causing pain and blistering on the lips and perioral area (cold sores). Stress is an important precipitating factor in subjects with recurrent herpes labialis, involving modulations of T-lymphocyte function [36].

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivostomatitis (NUG) is a relatively uncommon disease characterized by gingival necrosis and ulceration, pain, and bleeding [37]. Emotional stress is one of the predisposing factors for NUG, and appears to play a role through induction of increased cortisol and catecholamine levels [38].

The literature has shown that stress and psychological factors are possible risk factors for periodontal disease [39,40]. Stress and depression may be associated with periodontal destruction through behavioral and physiologic mechanisms. Proper diagnosis and treatment of depression may be an important part of periodontal preventive maintenance.

Cancerophobia is the persistent fear in a patient's mind that he or she has contracted oral cancer. This has been observed to be associated with depression. Cancerophobia is often seen in association with burning mouth syndrome [13].

Go to :

Future revisions and updates may be required with the further progress of time and knowledge. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a common psychological syndrome in dental practice which results in patients seeking treatment for an imagined defect in appearance [41]. Therefore, the author has added one more subset to the existing classification, i.e., V = Disorders caused by altered perception of dentofacial form and function, which include body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). After the inclusion of the subset (disorders caused by altered perception of dentofacial form and function), the terminology "psychosomatic disorders of the oral cavity" is modified to "psychosomatic disorders pertaining to dental practice". In the revised working type classification, miscellaneous disorders is shifted from V to VI with the addition of delusional halitosis under the miscellaneous disorders classification of psychosomatic disorders. A revised simple working type classification is proposed here for psychosomatic disorders pertaining to dental practice with their clinical presentation (Table 1).

Go to :

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a psychological syndrome which results in patients seeking treatment for an imagined defect in their appearance [41]. Many patients present with a negative "feeling" about their exaggerated perception of a minimal dentofacial disorder of form and function or an also negative "phantom" dysmorphia. Aesthetic dental treatment for such patients is not beneficial and carries some potential risks [42].

Go to :

Halitosis or oral malodor or bad breath is a common concern for millions of people [43]. Delusional halitosis is a psychosomatic condition in which some individuals have the belief that they have an offensive mouth odor which neither the dental clinician nor any other clinician can perceive [44]. Delusional halitosis may be characterized as pseudo-halitosis or halitophobia, depending on the response to initial treatment.

Halitophobia is an olfactory reference syndrome and is a psychological condition that the dental surgeon is illequipped to treat alone. Delusional halitosis may present clinically as a spectrum ranging from an overvalued belief to a frank delusional disorder in which the individual can hardly be dissuaded from his or her belief of mouth odor; in other words the person will be presenting with false offensive mouth odor. Both Pseudo-halitosis and halitophobia patients must be referred to psychological specialists [45].

Go to :

To conclude, psychosomatic disorders pertaining to dental practice are presented here with a revised working type classification. In the revised working type classification, the terminology "psychosomatic disorders of the oral cavity" is modified to "psychosomatic disorders pertaining to dental practice". The psychosomatic etiology is already proposed for orofacial pain in dental practice [46]. Measures should be taken to incorporate this revised classification into the DSM-5 classification system and also to evaluate the validity of this classification.

Go to :

References

1. Aksoy N. Psychosomatic diseases and dentistry (report of two psychoneurotic cases). Ankara Univ Hekim Fak Derg. 1990; 17:141–143. PMID: 2104047.

2. Yoshikawa T, Toyofuku A. Psychopharmacology and oral psychosomatic disorder. Nihon Rinsho. 2012; 70:122–125. PMID: 22413505.

3. Shamim T. A simple working type classification proposed for the psychosomatic disorders of the oral cavity. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2012; 22:612. PMID: 22980624.

4. van Selms MK, Lobbezoo F, Visscher CM, Naeije M. Myofascial temporomandibular disorder pain, parafunctions and psychological stress. J Oral Rehabil. 2008; 35:45–52. PMID: 18190360.

5. Kim YK, Kim SG, Im JH, Yun PY. Clinical survey of the patients with temporomandibular joint disorders, using Research Diagnostic Criteria (Axis II) for TMD: preliminary study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012; 40:366–372. PMID: 21745749.

6. Quail G. Atypical facial pain--a diagnostic challenge. Aust Fam Physician. 2005; 34:641–645. PMID: 16113700.

7. Pasqualini D, Scotti N, Ambrogio P, Alovisi M, Berutti E. Atypical facial pain related to apical fenestration and overfilling. Int Endod J. 2012; 45:670–677. PMID: 22309707.

8. Baad-Hansen L. Atypical odontalgia - pathophysiology and clinical management. J Oral Rehabil. 2008; 35:1–11. PMID: 18190356.

9. Koratkar H, Koratkar S. Atypical odontalgia: a case report. Gen Dent. 2008; 56:353–355. PMID: 19284197.

10. Clark GT. Persistent orodental pain, atypical odontalgia, and phantom tooth pain: when are they neuropathic disorders? J Calif Dent Assoc. 2006; 34:599–609. PMID: 16967670.

11. Marbach JJ. Orofacial phantom pain: theory and phenomenology. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996; 127:221–229. PMID: 8682991.

12. Ligas BB, Galang MT, BeGole EA, Evans CA, Klasser GD, Greene CS. Phantom bite: a survey of US orthodontists. Orthodontics (Chic). 2011; 12:38–47. PMID: 21789289.

13. Sardella A. An up-to-date view on burning mouth syndrome. Minerva Stomatol. 2007; 56:327–340. PMID: 17625490.

14. Kenchadze R, Iverieli M, Okribelashvili N, Geladze N, Khachapuridze N. The psychological aspects of burning mouth syndrome. Georgian Med News. 2011; (194):24–28. PMID: 21685517.

15. Rayman S, Dincer E, Almas K. Xerostomia. Diagnosis and management in dental practice. N Y State Dent J. 2010; 76:24–27. PMID: 20441043.

16. Bergdahl M, Bergdahl J, Johansson I. Depressive symptoms in individuals with idiopathic subjective dry mouth. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997; 26:448–450. PMID: 9416574.

17. Brennan MT, Elting LS, Spijkervet FK. Systematic reviews of oral complications from cancer therapies, Oral Care Study Group, MASCC/ISOO: methodology and quality of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2010; 18:979–984. PMID: 20306090.

18. Landis BN, Just T. Taste disorders. An update. HNO. 2010; 58:650–655. PMID: 20607505.

19. Satoh T. Clinical and fundamental investigations on recurrent glossodynia. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2004; 45:233–237. PMID: 15550921.

20. Terai H, Shimahara M. Glossodynia from Candida-associated lesions, burning mouth syndrome, or mixed causes. Pain Med. 2010; 11:856–860. PMID: 20624240.

21. Kramp B, Graumüller S. Glossopyrosis--diagnosis and therapy. Laryngorhinootologie. 2004; 83:249–262. PMID: 15088200.

22. Henkin RI, Gouliouk V, Fordyce A. Distinguishing patients with glossopyrosis from those with oropyrosis based upon clinical differences and differences in saliva and erythrocyte magnesium. Arch Oral Biol. 2012; 57:205–210. PMID: 21937022.

23. Slavicek R, Sato S. Bruxism--a function of the masticatory organ to cope with stress. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2004; 154:584–589. PMID: 15675433.

24. Lavigne GJ, Khoury S, Abe S, Yamaguchi T, Raphael K. Bruxism physiology and pathology: an overview for clinicians. J Oral Rehabil. 2008; 35:476–494. PMID: 18557915.

25. Ferreira-Bacci Ado V, Cardoso CL, Díaz-Serrano KV. Behavioral problems and emotional stress in children with bruxism. Braz Dent J. 2012; 23:246–251. PMID: 22814694.

26. Glass LF, Maize JC. Morsicatio buccarum et labiorum (excessive cheek and lip biting). Am J Dermatopathol. 1991; 13:271–274. PMID: 1867357.

28. Pokupec JS, Gruden V, Gruden V Jr. Lichen ruber planus as a psychiatric problem. Psychiatr Danub. 2009; 21:514–516. PMID: 19935485.

29. Chattopadhyay A, Shetty KV. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011; 44:79–88. PMID: 21093624.

30. Gallo Cde B, Mimura MA, Sugaya NN. Psychological stress and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009; 64:645–648. PMID: 19606240.

31. Rieder E, Tausk F. Psoriasis, a model of dermatologic psychosomatic disease: psychiatric implications and treatments. Int J Dermatol. 2012; 51:12–26. PMID: 22182372.

32. Tomb R, Hajj H, Nehme E. Oral lesions in psoriasis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010; 137:695–702. PMID: 21074652.

33. Chan LS. Ocular and oral mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid). Clin Dermatol. 2012; 30:34–37. PMID: 22137224.

34. Joseph TI, Vargheese G, George D, Sathyan P. Drug induced oral erythema multiforme: a rare and less recognized variant of erythema multiforme. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012; 16:145–148. PMID: 22434953.

35. Kamala KA, Ashok L, Annigeri RG. Herpes associated erythema multiforme. Contemp Clin Dent. 2011; 2:372–375. PMID: 22346171.

36. Schmidt DD, Schmidt PM, Crabtree BF, Hyun J, Anderson P, Smith C. The temporal relationship of psychosocial stress to cellular immunity and herpes labialis recurrences. Fam Med. 1991; 23:594–599. PMID: 1794671.

37. Diouf M, Cisse D, Faye A, Niang P, Seck I, Faye D, et al. Prevalence of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis and associated factors in Koranic boarding schools in Senegal. Community Dent Health. 2012; 29:184–187. PMID: 22779382.

38. Johnson BD, Engel D. Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. A review of diagnosis, etiology and treatment. J Periodontol. 1986; 57:141–150. PMID: 3514841.

39. Peruzzo DC, Benatti BB, Ambrosano GM, Nogueira-Filho GR, Sallum EA, Casati MZ, et al. A systematic review of stress and psychological factors as possible risk factors for periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2007; 78:1491–1504. PMID: 17668968.

40. Rai B, Kaur J, Anand SC, Jacobs R. Salivary stress markers, stress, and periodontitis: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2011; 82:287–292. PMID: 20722529.

41. Scott SE, Newton JT. Body dysmorphic disorder and aesthetic dentistry. Dent Update. 2011; 38:112–114. 117–118. PMID: 21500621.

42. Polo M. Body dysmorphic disorder: a screening guide for orthodontists. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 139:170–173. PMID: 21300244.

43. Bollen CM, Beikler T. Halitosis: the multidisciplinary approach. Int J Oral Sci. 2012; 4:55–63. PMID: 22722640.

44. Uguru C, Umeanuka O, Uguru NP, Adigun O, Edafioghor O. The delusion of halitosis: experience at an eastern Nigerian tertiary hospital. Niger J Med. 2011; 20:236–240. PMID: 21970235.

45. Yaegaki K, Coil JM. Genuine halitosis, pseudo-halitosis, and halitophobia: classification, diagnosis, and treatment. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2000; 21:880–886. 888–889. PMID: 11908365.

46. Shamim T. A simple working classification proposed for orofacial pain (OFP) commonly encountered in dental practice. Korean J Pain. 2013; 26:407–408. PMID: 24156011.

Go to :

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download