Abstract

The hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bone is usually asymptomatic, but it is not uncommon for it to be symptomatic in cases of undue pressure, overuse, or trauma. Even in symptomatic cases, however, patients often suffer for extended periods due to misdiagnosis, resulting in depression and anxiety that can steadily worsen to the extent that symptoms are sometimes mistaken for a somatoform disorder. Dynamic ultrasound-guided evaluations can be an effective means of detecting symptomatic sesamoid bones, and a simple injection of a small dose of local anesthetics mixed with steroids is an easily performed and effective treatment option in cases, for example, of tenosynovitis.

The global prevalence of hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones is approximately 27.5% [1,2]. It can become symptomatic in cases of undue pressure, overuse, or trauma, at which times the tendon of the flexor hallucis longus, due to its anatomical location, is typically the most affected. In most cases, however, the hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones remain asymptomatic. For this reason, physicians tend to overlook this structure as a possible source of pain. Thus, misdiagnosed patients often suffer pain and walking difficulties for extended periods; even worse, they stand a fair chance of being shunted between medical departments and ultimately hospitalized for a somatoform disorder.

Here, we present the case of a patient who was misdiagnosed with a somatoform disorder before being correctly diagnosed at our pain clinic with symptomatic hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones after a careful review of the patient's history taking and physical examination. Thereafter, the patient was successfully treated by means of ultrasound-guided evaluation and the injection of a small dose of local anesthetics mixed with steroids.

A 29-year-old woman presenting with lower-extremity pain and walking difficulties was referred by the department of neuropsychiatry to our clinic. Her pain, which was in the toes, was described as continuous, throbbing, crushing, and burning, and its intensity was registered as 8 on the 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). At night, her pain was severe enough to wake her frequently.

According to her medical history, these symptoms had arisen 9 months previously (3 months postpartum) and were accompanied by postpartum depression. Orthopedic, neurologic, rheumatologic, and endocrinologic examinations had been unable to reveal the cause of her pain. Eventually, she had been referred to a psychiatrist for a somatoform disorder and then admitted to the psychiatric ward. At the hospital, she had been treated for painful legs and moving toes (PLMT) syndrome, but the symptoms had persisted. As time passed, her depression had steadily worsened. The patient had then been scheduled for consultation with a pain specialist.

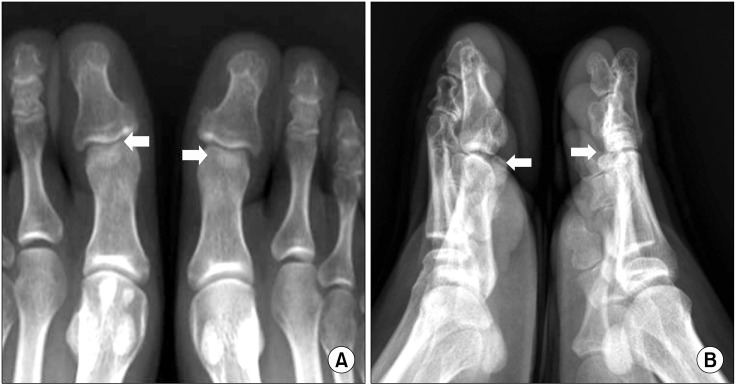

As a last resort, she visited our clinic. We reevaluated her problem, taking special note of the directionality of her pain, which originated at the great toes and extended to her calves (Fig. 1). On physical examination, there was tenderness at the base of the great toes bilaterally, and this tenderness increased, becoming pain, particularly during dorsiflexion. On the basis of an ultrasonographic foot evaluation, we found sesamoid bones on each interphalangeal joint of the hallux under the flexor hallucis longus tendon (Fig. 2), which had been overlooked on plain radiographs (Fig. 3).

Furthermore, in a dynamic examination involving the application of a USG probe and passive extension and flexion of the hallux, we were able to diagnose the influence of symptomatic interphalangeal sesamoids on the flexor hallucis longus tendon. The patient was treated through an ultrasound-guided injection of 1 ml of 0.125% levobupivacaine (Chirocaine®, Abbott, Elverum, Norway) mixed with 10 mg of triamcinolone acetonide between the sesamoid bone and flexor hallucis longus tendon at each site. The patient's pain immediately subsided.

The following day, the patient reported no pain and, with her doctor's permission, went shopping. Subsequently, she was discharged in a state of complete remission. From that day to the present, her depression has also greatly improved.

The accessory ossicles and sesamoid bones of the ankle and foot are anatomic variants that usually remain asymptomatic. Interestingly, radiographic findings on the hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones suggest that race may have a strong predisposing effect: similarly high prevalence rates of 89.3% and 91% have been reported among Korean and Japanese subjects, respectively, whereas the rates are only 13% among North American, 3.9% among Bahraini, 2% among Turkish, and 0% among black African subjects [2-5]. Even so, it should be noted that such differences may reflect factors other than race (e.g. technical variations in radiography leading to underestimation and/or variability in the degree of sesamoid ossification). In any event, asymptomatic sesamoids are present in a large percentage of the Korean population and can become symptomatic (i.e., painful) with degenerative changes resulting from undue pressure, overuse, or trauma [6].

For imaging evaluation, conventional radiography (i.e., lateral and dorsoplantar views of the foot and a special axial projection of the sesamoids) is initially recommended [7]. However, due to incomplete ossification, sesamoids can be overlooked on initial radiographs. In addition, because sesamoid bones are small, oval, rough, convex in shape, and composed mainly of bone, cartilage, and fibrous tissue, their contours on radiographs often are obscured by the opacity of the larger bones [1,8]. Thus, when patients suffer from foot pain of unknown origin, the hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones need to be considered as a possible differential diagnosis, especially when radiographs are inconclusive. In such cases, scintigraphy, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging can be used [7]. Indeed, misdiagnosis remains the most serious problem in cases of hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones. Patients often are falsely suspected of having a somatoform disorder, which itself can lead to depression and anxiety. The depression and anxiety can become more severe over time as the pathology continues to be invisible and/or overlooked on radiographs or misdiagnosed upon examination. Therefore, physicians should practice detailed history-taking and conduct thorough examinations when seeking to identify the causes of pain. Differential diagnoses of sesamoid pain include sprain, fracture, osteonecrosis, degenerative joint disease, chronic bursitis, and neural entrapment, among others [7,9]. Ultrasound is particularly effective in the diagnosis of a variety of musculoskeletal disorders [10]; hallucal interphalangeal sesamoids, as a kind of sesamoid, are characterized with regard to location, contour, echogenicity, and shadowing [11]. Moreover, good results can be obtained in the treatment, for example, of tenosynovitis through USG-guided injections of small doses of local anesthetics mixed with steroids between the interphalangeal sesamoid bone and the flexor hallucis longus [12].

Treatment of symptomatic hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones is basically conservative. The purpose of management is to eliminate inflammation and predisposing factors. In cases where conservative therapy is ineffective, surgical excision may be the next-best option [8,13]. Although excision undoubtedly provides the most effective relief, less invasive methods for treating symptomatic sesamoid bones need to be considered prior to surgical intervention. The aforementioned ultrasound-guided injection is one such option.

The present case, involving a 29-year-old woman who presented to our clinic with lower-extremity pain and walking difficulties, demonstrates that careful history-taking and symptom provocation technique during physical examination are essential for the proper diagnosis of hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid bones and, thus, effective pain management. Additionally, this case confirms that dynamic USG, especially in the digital area, is useful for both diagnosis and treatment.

References

1. Roukis TS, Hurless JS. The hallucal interphalangeal sesamoid. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1996; 35:303–308. PMID: 8872752.

2. Davies MB, Abdlslam K, Gibson RJ. Interphalangeal sesamoid bones of the great toe: an anatomic variant demanding careful scrutiny of radiographs. Clin Anat. 2003; 16:520–521. PMID: 14566900.

3. Coskun N, Yuksel M, Cevener M, Arican RY, Ozdemir H, Bircan O, et al. Incidence of accessory ossicles and sesamoid bones in the feet: a radiographic study of the Turkish subjects. Surg Radiol Anat. 2009; 31:19–24. PMID: 18633564.

4. Moon SH, Kim DJ, Suh BH. Radiological study of interphalangeal sesamoid bones on hallux in Korean subjects. J Korean Foot Ankle Soc. 2006; 10:242–246.

5. Dharap AS, Al-Hashimi H, Kassab S, Abu-Hijleh MF. Incidence and ossification of sesamoid bones in the hands and feet: a radiographic study in an Arab population. Clin Anat. 2007; 20:416–423. PMID: 16944528.

6. Mellado JM, Ramos A, Salvadó E, Camins A, Danús M, Saurí A. Accessory ossicles and sesamoid bones of the ankle and foot: imaging findings, clinical significance and differential diagnosis. Eur Radiol. 2003; 13(Suppl 4):L164–L177.

7. Taylor JA, Sartoris DJ, Huang GS, Resnick DL. Painful conditions affecting the first metatarsal sesamoid bones. Radiographics. 1993; 13:817–830. PMID: 8356270.

8. Del Rossi G. Great toe pain in a competitive tennis athlete. J Sports Sci Med. 2003; 2:180–183.

9. Wall J, Feller JF. Imaging of stress fractures in runners. Clin Sports Med. 2006; 25:781–802. PMID: 16962426.

10. Patil P, Dasgupta B. Role of diagnostic ultrasound in the assessment of musculoskeletal diseases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2012; 4:341–355. PMID: 23024711.

11. Brigido MK, Fessell DP, Jacobson JA, Widman DS, Craig JG, Jamadar DA, et al. Radiography and US of os peroneum fractures and associated peroneal tendon injuries: initial experience. Radiology. 2005; 237:235–241. PMID: 16183934.

12. Wempe MK, Sellon JL, Sayeed YA, Smith J. Feasibility of first metatarsophalangeal joint injections for sesamoid disorders: a cadaveric investigation. PM R. 2012; 4:556–560. PMID: 22484333.

13. Coughlin MJ. Coughlin MJ, Mann RA, Saltzman CL, editors. Sesamoids and accessory bones of the foot. Surgery of the foot and ankle. 2007. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby;p. 566–567.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download