Abstract

Background

Hemorrhoid is one of the most common surgical diseases occurring in the anorectal region. In this study, we evaluated the effect of ischiorectal fossa block on alleviating post hemorrhoidectomy pain.

Methods

In this study, 90 patients suffering from hemorrhoids were evaluated. They were randomly divided into 3 groups. The first group had no block, the second group an ischiorectal block with placebo (normal saline), and the third group a preemptive ischiorectal block with bupivacaine. Postoperative variables such as pain intensity, pethidine consumption, nausea, and vomiting were compared between the groups.

Results

The postoperative pain score in group 1 was 8.5 ± 1.3 and 8.1 ± 0.9 (P = NS) in group 2. The post operative analgesic demand was 3.1 ± 1.5 and 3.3 ± 1.8 hours in groups 1 and 2, respectively (P = NS). The post operative pain score and analgesic demand were 4.2 ± 2.1 and 9.3 ± 2.7 hours, respectively, in group 3 (P < 0.0001).

Hemorrhoid is one of the most common surgical diseases occurring in the anorectal region presenting with pain, bleeding and mass appearance in the rectum [1]. Hemorrhoid and other anorectal disorders have been reported to occur in 4-5 percent of adults, 10% of whom need to undergo an operation [2]. Hemorrhoid surgery requires deep anesthesia because the zone has multiple nerve supply and is reflexogenic. Operations under light anesthesia cause intense pain, reflex body movements, tachypnea and laryngeal spasm. Pain management, especially during the first 24 hours following the operation, results in a reduction of urinary retention and constipation as well as increased patient satisfaction [3]. In a case reviewing the data of over 110 patients undergo an operation, 35% of them suffered moderate to severe pain at home despite taking painkillers [4]. In addition, the inadequate management of postoperative pain increases the need for opioids [5] which itself causes nausea and vomiting after surgery [6].

Although several methods including general, spinal, caudal, local and combined techniques have been used for hemorrhoid surgery, there is no ideal method with each of them having advantages and disadvantages. Regional anesthesia provides preemptive analgesia. It can reduce or avoid the hazards and discomforts of general anesthesia including sore throat, airway trauma and muscle pain. It is easily learned and simple to perform; when used in surgical patients, it does not appear to significantly interfere with the progression of the surgery; and it is generally safe for patients as long as the anesthetic is not injected intravascularly and excessive doses are not administered. But regional anesthesia also possesses disadvantages such as drug reactions. Pudendal nerve block can result in complications such as hematoma, trauma to the sciatic nerve and puncture of the rectum. As this is a blind technique in a vascular region near the bowel and bladder, they direct a needle, by palpation, along the course of their fingers to palpate the appropriate landmarks. This places such physicians at high risk for accidentally puncturing their fingers with the needle.

Many studies have been done to reduce patients' pain including local injection of fentanyl, epidural injection of morphine, external sphincter injection of ketorolac and injection of dextromethorphan [7,8]. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of preoperative ischiorectal fossa block with bupivacaine 0.25% on alleviating posthemorrhoidectomy pain and its related side effect such as pethidine consumption, nausea and vomiting [9].

Ischiorectal fossa is a wedge shaped space situated on either side of the anal canal below the pelvic diaphragm. The base is directed downwards towards the skin. It is 5 to 6 cm deep, anteroposteriorly 5 cm, and 2.5 cm side to side, lying below the levator ani muscles and on either side of the anal canal. Pudendal canal is a fascial tunnel present in the lower part of the lateral wall of the Ischiorectal fossa, just above the sacrotuberous ligament. The pudendal canal is formed by splitting of the fascia lunata. The fascial wall of the canal is fused laterally to the obturator fascia, medially to the perineal fascia, and inferiorly with the sacrotuberous ligament. It contains the pudendal nerve and the internal pudendal vessels.

Ischiorectal fossa block was performed as follows: The patient was placed in the lithotomy position. After appropriate preparation of the skin, the point of needle insertion was identified. This point, located by palpating the tuberosity of the ischium, lies 2.5 cm posteromedial to the latter structure. A skin wheal was made with a 25-gauge needle, after which a 20-cm 20-gauge needle was introduced at a right angle to the skin on all planes. The syringe was not attached until the needle reached its final position. The left index finger was inserted into the rectum to guide the needle, palpate the ischial spine, and prevent the needle from passing through the rectum. The syringe was not connected, and an aspiration test was performed while the needle was rotated 180 degrees. If this test was negative, 15 ml local anesthetic was injected. The needle was then advanced another 1 cm, and a further attempt to aspirate was made and another 5 ml of local anesthetic was injected. The same procedure was carried out on the other side.

This study was performed on 90 patients who were admitted to the study hospital for hemorrhoid surgery. Patients with a grade 1 hemorrhoid or a past history of cardiovascular diseases were excluded. The study was approved by the university ethical committee. The patients were randomly divided into 3 groups. In the first group, surgery was performed without ischiorectal block. In the second group, preoperative ischiorectal block was performed with placebo (normal saline). In the third group, preoperative ischiorectal block was performed with bupivacaine 0.25%. Bupivacaine with the trade name of Marcaine belongs to the amides group of local anesthetic drugs. This drug has a long-effect; its influence begins in 4 to 10 minutes with the effect lasting for 1.5 to 8.5 hours, and it was selected in this study based on its long-effect.

Random intervention allocation was carried out for each patient after evaluating the inclusion criteria and receiving written and informed consent of the patients taken by the ward nurse. She registered entering each patient into the study and randomly opened his/her envelope, determining the type of intervention (group 1 to 3). The patient was blind to the type of intervention, but the doctor was not blind to the nature of the intervention. However, in assessing the pain and postoperative side effects, the surgeon was blinded to the type of intervention. Assessment of postoperative variables such as pain intensity, nausea, and vomiting was administered by a trained nurse in the ward. All patients underwent general anesthesia with the same procedure. To induce general anesthesia, 2 µg/kg of fentanyl and 1-2 mg/kg of propofol were used. Isoflurane (0.8 to 1 percent of current volume), 50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen were administered for maintenance. Submucosal hemorrhoidectomy was performed by the Ferguson method. The intensity of the pain tolerated by the patient was registered 12 hours after the surgery using the visual analog scale (VAS 0-10, where 0 represented no pain and 10 represented the worst pain imaginable). The patient's information was extracted from reception forms and the necessary data was analyzed according to the appropriate frequency table and variables. One checklist was used to evaluate the adverse effects of bupivacaine such as central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular effects.

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 13. We used the Leven, T test, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for the statistical analyses. A P less than 0.05 was considered significant.

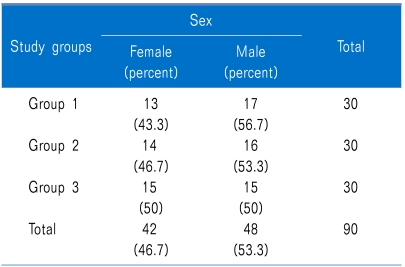

53.3% of the patients were male (48 cases) and 46.7% (42 cases) were women (P = NS) (Table 1).

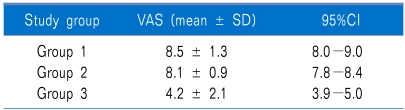

The mean postoperative pain score was 8.5 ± 1.3 in group 1 and 8.1 ± 0.9 in group 2 (P = NS). The mean postoperative pain score in group 3 was 4.2 ± 2.1. A significant statistical difference was noted in the postoperative pain score of group 3 compared with the other groups (P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

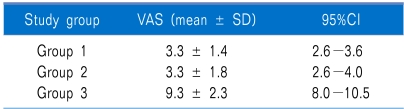

The mean time for first analgesic demand after the operation was 3.1 ± 1.5 and 3.3 ± 1.8 hours for group 1 and 2, respectively (P = NS). The mean time for first analgesia demand after the operation among the patients of group 3 was 9.3 ± 2.7 hours. A significant statistical difference was noted in the mean time for first analgesic demand in group 3 compared with the other groups (P < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Twenty (22.2%) of the patients had nausea (8 (26.7%) in group 1, 8 (26.7%) in group 2, and 4 (13.3%) in group 3) (P = NS).

Five (5.6%) of the patients had vomiting (3 (10%) in group 1, 2 (6.7%) in group 2, and none in group 3) (P = NS). We had no adverse effects for bupivacaine in our patients.

Preemptive analgesia reduces postoperative complications, implementing the preemption mechanism of pain receptor bombardment in the central nervous system. The incision from the surgery does not stimulate the pain receptor per se, but chemical mediums and enzymes released from the injured tissue cause pain [10]. It is desirable that methods and drugs used for regional anesthesia in an ambulatory setting possess the same properties as drugs used for ambulatory general anesthesia, i.e. rapid onset of action, adequate surgical anesthesia, and rapid achievement of discharge criteria such as ambulation and urination.

It has been suggested that nerve block before and after operation is a very effective method to reduce postoperative pain because it reduces the pain and causes hypesthesia in both levels of pain (one caused by the incision and the other by the agitated response from the traumatized tissue). On the other hand, pain control, especially during the first 24 hours after the surgery, increases patient satisfaction as well as decreases urinary retention and constipation [3].

In Imbelloni's work in 2007 in Brazil, 100 patients who need a hemorrhoidectomy were divided into two groups (with and without ischiorectal block with bupivacaine). This study showed that a pudendal nerve block alleviated the pain intensity at 6, 12, and 18 hours postoperatively when comparing between the control and case group [11]. In our study, we used a routine technique for the block; however, in the Imbelloni study [11], the authors used the nerve stimulator guided technique and spinal anesthesia. The mean analgesic duration was longer in their study. It seems that with better orientation of the nerve, the analgesic duration will be prolonged. On the other hand, all patients in the Imbelloni study were given spinal anesthesia and this can be another important difference. These results are also repeated in other studies [12,13].

These recent studies confirm that nerve block by local analgesic drugs brings a balance to the patient's response to surgical damage [14]. Administration of a nerve block using local analgesics decreases the physiological responses to surgery, especially in the lower abdomen and pelvic organs as well [15].

However, in some studies, no direct relation was found between local anesthesia and a reduction in pain after the operation including a study by Rodrigues in Brazil [16]. In the Brazil study, a randomized, double-blind study, children undergoing surgeries for club foot were divided in four groups according to the anesthetic technique: caudal, sciatic and femoral block, sciatic and saphenous block, and sciatic block and local anesthesia, associated with general anesthesia. Their results showed that the mean time between the blockade and the first dose of morphine was 6.16 hours in group one, 7.05 hours in group two, 7.58 in group three, and 8.18 hours in the last group; however, significant differences were not observed among the groups. The mean time between the blockade and the first dose of morphine in group 3 was similar with the result of our study. However, they did not include a general anesthesia or placebo group.

In conclusion, our findings show that an ischiorectal block before hemorrhoidectomy clearly reduced the postoperative pain and opioid dosage.

References

1. Mukhashavria GA, Qarabaki MA. Circumferential excisional hemorrhoidectomy for extensive acute thrombosis: a 14-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011; 54:1162–1169. PMID: 21825898.

2. Greco DP, Miotti G, Della Volpe A, Magistro C, De Carli S, Pugliese R. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy: day surgery or one day surgery? Surg Oncol. 2007; 16(Suppl 1):S173–S175. PMID: 18063361.

3. Liu ST, Wu CT, Yeh CC, Ho ST, Wong CS, Jao SW, et al. Premedication with dextromethorphan provides posthemorrhoidectomy pain relief. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000; 43:507–510. PMID: 10789747.

4. Watt-Watson J, Chung F, Chan VW, McGillion M. Pain management following discharge after ambulatory same-day surgery. J Nurs Manag. 2004; 12:153–161. PMID: 15089952.

5. Klein SM, Bergh A, Steele SM, Georgiade GS, Greengrass RA. Thoracic paravertebral block for breast surgery. Anesth Analg. 2000; 90:1402–1405. PMID: 10825328.

6. Singelyn FJ, Aye F, Gouverneur JM. Continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block: an original technique to provide postoperative analgesia after foot surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997; 84:383–386. PMID: 9024034.

7. Kilbride M, Morse M, Senagore A. Transdermal fentanyl improves management of postoperative hemorrhoidectomy pain. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994; 37:1070–1072. PMID: 7956571.

8. Chester JF, Stanford BJ, Gazet JC. Analgesic benefit of locally injected bupivacaine after hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990; 33:487–489. PMID: 2351001.

9. Brunicardi FC, Brandt ML, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, et al. Schwartz's principles of surgery. 2010. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;p. 342–358.

10. Lally KP, Cox CS Jr, Andrassy RJ. Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers ME, Mattox KL, editors. History of appendicitis. Sabistone textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. 2001. 16th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;p. 919.

11. Imbelloni LE, Vieira EM, Gouveia MA, Netinho JG, Spirandelli LD, Cordeiro JA. Pudendal block with bupivacaine for postoperative pain relief. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007; 50:1656–1661. PMID: 17701375.

12. Naja Z, Ziade MF, Lönnqvist PA. Nerve stimulator guided pudendal nerve block decreases posthemorrhoidectomy pain. Can J Anaesth. 2005; 52:62–68. PMID: 15625258.

13. Naja Z, El-Rajab M, Al-Tannir M, Ziade F, Zbibo R, Oweidat M, et al. Nerve stimulator guided pudendal nerve block versus general anesthesia for hemorrhoidectomy. Can J Anaesth. 2006; 53:579–585. PMID: 16738292.

14. Crile GW. Phylogenetic association in relation to certain medical problems. Boston Med Surg J. 1910; 163:893–904.

15. Kehlet H. The modifying effect of anesthetic technique on the metabolic and endocrine responses to anesthesia and surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 1988; 39:143–146. PMID: 3057785.

16. Rodrigues MR, Paes FC, Duarte LT, Nunes LG, Costa VV, Saraiva RA. Postoperative analgesia for the surgical correction of congenital clubfoot: comparison between peripheral nerve block and caudal epidural block. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2009; 59:684–693. PMID: 20011858.

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download